Colligation: classification by syntactic properties

A definition

This is a term often contrasted with collocation

(to which there is a

separate guide on this site).

The clue is in the name:

- collocation derives from the Latin collocare meaning place together. It refers to items in the language which are conventionally found together, placed that way, in other words.

- colligation derives from the Latin colligare meaning tie together. It refers to items which form a set of items with syntactically identical properties. Such items are said to colligate. A careful definition is:

A term ... for the process or result of

grouping a set of words on the basis of their similarity in entering

into syntagmatic grammatical relations.

(Crystal, 2008:86)

By this strict definition, it is inaccurate to speak of

item X colligating with structure Y

in the same way that we talk about

lexical item X collocating with

lexical item Y. Colligation refers to sets of

items which are primed to co-occur with certain grammatical

structures. We should not, therefore, use terms such as:

The verbs speak and tell

colligate differently

but prefer

The verbs speak and tell

belong to different colligations.

In what follows, we'll try to keep to this principle although the

temptation to refer to a single item's colligational characteristics

is always strong.

|

An explanation of syntagmatic |

Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations

Take the sentence:

- He bought a hat.

In this sentence, hat can be replaced by almost any noun but it must be a noun or a noun phrase. Likewise, bought can be replaced by many verbs but they must be verbs or a verb phrase. So we can get, e.g.:

- He sold a hat.

- He bought a car.

- He stole a gadget.

- Syntagmatic relationship

- This describes the relationship between, e.g., He, bought

and a hat in Sentence 1, He, sold and

a hat in Sentence 2, He, bought

and a car in sentence3 and He and stole

and a gadget in Sentence 4.

These relationships work horizontally between words. Subjects use Verbs, Verbs sometimes take Objects, Adjectives modify Nouns, Adverbs modify Verbs and so on. The relationship is to do with syntax (hence the name). - Paradigmatic relationships

- These are exemplified by the changes we have made between the

sentences and describe the relationships between:

bought, sold and stole

car, gadget and hat

These relationships work vertically in the sense that Noun phrases can be replaced by other Noun phrases, Verb phrases by other Verb phrases, Adjectives by other Adjectives, Adverbs by other Adverbs and so on. The relationship is to do with word and phrase class.

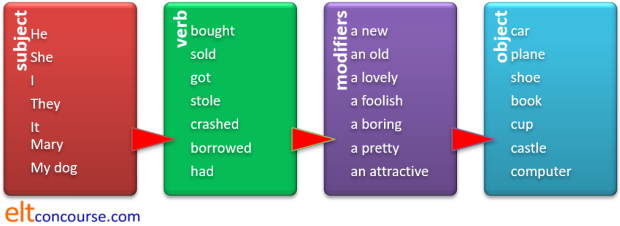

It all works like this:

The words in each box have paradigmatic relationships to each other. The red arrows show the syntagmatic relationships.

collocation and colligation

- Collocation

- is one type of syntagmatic relationship describing the

phenomenon we observe of, e.g., the adjective genuine

often being seen in conjunction with a noun like

article, painting, excuse, antique etc. but not with

money, pen, computer, glass etc. In the same vein, we

close the door but switch

off a light. Some languages will use the

same verb for both.

There is a guide to collocation linked in the list of related guides at the end. - Colligation

- describes a different but allied relationship. Just as

an adjective can be, as it were, primed to appear before a

particular set of nouns so can a word be primed to enter into

certain grammatical relationships. For example, the verbs

allow, permit, forbid, enable are often seen in

constructions like:

I allowed him to go

Mary permitted him to come

I forbade him to speak

The operation enabled him to walk

Where the form is: Subject (often but not always human) + object (often human) + to + verb.

Moreover, the second verb in such structures is usually dynamic rather than stative in use. Things like:

I allowed him to understand

They permitted him to be

are vanishingly rare.

Other verbs which may mean very similar things such as authorise, let, approve, tolerate, consent will not enter the same sorts of syntactical relationships so are not colligates of allow, permit, forbid etc. We cannot, therefore, say:

*I let him to come

*I consented him to come

and so on.

Both colligation and collocation are language-specific phenomena. What collocates in one language may not in another and the same applies to colligation.

Collocational phenomena are sometimes described in terms of what

is 'done' and 'not done' in the language so we prefer, for example:

a wide street

to

a broad street

and

a narrow street

to

a thin street

although we are quite happy with both

a narrow line

and

a thin line.

By the same token, colligation can be described in terms of what is done and not done in the language but the advantage of looking at colligation over collocation is that colligation can be explained and taught on the basis of patterning in the language which follows rules. That's much harder to do with collocation because that phenomenon seems, superficially at least, random.

Unlike collocation, in which it is possible to identify a range of simple types, adjective + noun, verb + noun, adverb + adjective etc., colligation is a somewhat more slippery concept pedagogically. Nevertheless, Hoey suggests:

Colligations are particularly important

to learners of the language because they explain why it is that a

learner may feel he or she knows a word and yet produce a sentence

that is grammatical but ‘not English’.

(Hoey 2003)

|

Examples of colligational issues |

First, a simple test of your colligational competence

How do the verbs authorise, approve and

tolerate form colligates?

What kinds of subjects do they allow?

Are they transitive?

What kinds (if any) of objects do they allow?

Click here when you have an answer.

The usual way is in sentences such as:

They authorised his

visit.

They authorised the money.

The boss approved my expenses claim.

The boss approved the expenditure.

I tolerated his rudeness.

I tolerated the interruption.

In other words:

subject (almost

invariably human or animate at least) + possessive pronoun or

definite article + object (usually inanimate, often abstract).

The description of the type of subject or object (human vs.

inanimate) above is strictly speaking an aspect of collocation, not

colligation. The concepts overlap to some extent but the

nature of the subject or object of the verb is rarely mentioned in

the context of collocation where the focus is more firmly on meaning

and lexical relationships rather than structure. As we shall

see, the nature of the subject and the type of object in clauses is

often constrained by both meaning and structural characteristics.

This goes some way to explaining why a grammatically well-formed

utterance may not sound English.

There are some other phenomena associated with grammatical function.

We saw above how the verbs allow, permit, forbid and

enable colligate. These verbs frequently come in

clauses with this structure:

subject + verb + object (usually animate)

+ to + verb (dynamic not stative)

so we arrive at

| The teacher | allowed | the children | to | go home |

| The boss | enabled | his staff | to | have a holiday |

| She | forbade | him | to | shop |

and so on. Once the colligational structure of the verbs

has been mastered, it is possible to construct an almost infinite

number of correct clauses with the verbs. The nature of the

second verb also explains, incidentally, why:

She forbade him to be old

He permitted his mother to enjoy Mozart

It enabled Mary to like ice cream

are not English (i.e., wrong) even though they are, superficially at

least, grammatically well formed. These verbs, and many like

them, simply do not colligate with stative uses of other verbs.

As we also saw, the verbs authorise, approve

and tolerate although they are connected semantically

with allow, permit etc. colligate differently, not in terms of meaning but in terms of

the structures with which they occur. There is no obvious

semantic reason that we could not produce:

They enabled rudeness

but it is still 'not English'.

And, if we can say:

He allowed me to come

why is

He approved me to come

not permissible?

The answer is that it contravenes the colligational nature of the

verb and not that it is ungrammatical in terms of an overarching

structural rule.

|

issues of transitivity and intransitivity

|

We'll start with a simple example of colligational effects on how things are expressed in English. This issue is to with transitivity and, as we shall see, so are many others.

- I hid it in the cupboard

I concealed it in the cupboard

BUT - I hid behind my father

*I concealed behind my father

The verb conceal is always transitive, hide can be both.

|

the passive and issues of transitivity and intransitivity

|

There are three more-or-less synonymous verbs relating to

ownership but they have slightly different colligational

characteristics.

In the active voice we can accept:

The girl owns a book

The girl has a book

The girl possesses a book

and all three verbs are monotransitive so capable of forming a

passive construction.

However, when we try to make a passive, we run into:

The book is owned by the girl

*The book is had by the girl

*The book is possessed by the girl

and only the verb own can be used in a passive

construction.

The same phenomenon occurs with endure, stand for and

tolerate. We allow:

She endured his continual chatter

She stood for his continual chatter

She tolerated his continual chatter

but not:

*His continual chatter was endured by her

or

*His continual chatter was stood for by her

but we can have:

His continual chatter was tolerated by her

Finally, we have the issue of make and let

which differ in their grammatical, i.e., colligational

characteristics. We can have:

They made me go

and

They let me out

and in both cases, we use a bare infinitive for the second verb.

However, in the passive:

They were made to

go

and

I was let out

it is non-intuitive that make requires a different

grammatical construction (the to-infinitive) in

the passive from the one it uses in the active form but let

does not.

|

say, tell, talk and speak |

Because colligation varies across languages and translation is perilous, these four verbs cause a good deal of difficulty for learners. If, however, we look at colligational issues concerning transitivity and the types of objects the verbs allow, much becomes clearer.

- say

- is always a transitive verb but the objects it takes are

slightly anomalous:

- we allow direct speech to be the object:

He said, "Good morning" - we allow the description of a communicative function to

be the object

He said good morning

He said that's different - we allow a verb phrase plus the subject and the adjunct to be nominalised as the object:

He said that he was leaving today - we allow an inanimate noun phrase as the object if it

refers to something one can say:

He said his prayers

He said it aloud - we do not allow an inanimate object if

the verb means read aloud:

*He said the poem - we do not allow the verb to take an

animate object:

*He said Mary

*He said her - we do not allow an intransitive use (unless the object

is clearly omitted because it is understood):

*She said

*I have said

*Who is saying?

- we allow direct speech to be the object:

- speak

- is a verb which can be transitive or intransitive but,

again, the objects it takes are anomalous:

- we allow an inanimate noun phrase as the object only if it

refers to words or language:

He spoke the words

He spoke (in) German

I don't speak the language - we allow the verb to operate intransitively:

She spoke loudly to me

I have spoken

Will you speak at the meeting? - we do not allow an inanimate object if the verb means

read aloud:

*He spoke the poem - we do not allow direct speech to be the object:

*He spoke, "Good morning" - we do not allow a subject plus its verb phrase to be nominalised as the object:

He spoke that he was leaving today - we do not allow the verb to take an

animate object:

*He spoke Mary

*He spoke her

and must use a prepositional phrase with to:

He spoke to Mary

He spoke to her

- we allow an inanimate noun phrase as the object only if it

refers to words or language:

- talk

- is always intransitive

- we allow only intransitive uses:

She talked persuasively

They talked for hours

Will you talk at the conference? - we must use a prepositional phrase to introduce any

reference to what the talking was about or to

He talked to Mary

They talked about the programme

They talked in German - we allow only a language to appear to be the object of

the verb but then it acts as an adverbial rather than the

direct object:

They talked French together (meaning in French) - we do not allow true transitive use:

*They talked me

*They talked the book

*She talked the meeting

*She talked the poem - we do not allow a verb phrase plus its subject to be a nominalised

object:

*He talked that he was happy

*She is talking that she will leave soon

- we allow only intransitive uses:

- tell

- is always transitive and sometimes ditransitive (see below

for more)

- we allow an inanimate noun-phrase object:

He told a story

He told a lie - we allow ditransitive use with an animate indirect

object and a noun-phrase direct object:

He told the children a story

She told me the truth - we allow ditransitive use with an animate indirect

object and a nominalised verb-phrase direct object, usually

as reported speech:

He told her that he was going home

She told me where she got the book - we allow a single direct animate object only if

the indirect object (a noun phrase or nominalised verb

phrase) is understood:

She told the police

They told us - we only allow the to-infinitive as a

nominalised object in the sense of order:

They told me to go home - we allow direct speech to be the object:

He told me, "That's the train you want." - we do not allow a nominalised

verb-phrase object without an indirect object:

*She told that she was leaving

*They told to go away - we do not allow an intransitive use (even

if the object

is clearly omitted because it is understood):

*She told

*I have told

*Who is telling?

- we allow an inanimate noun-phrase object:

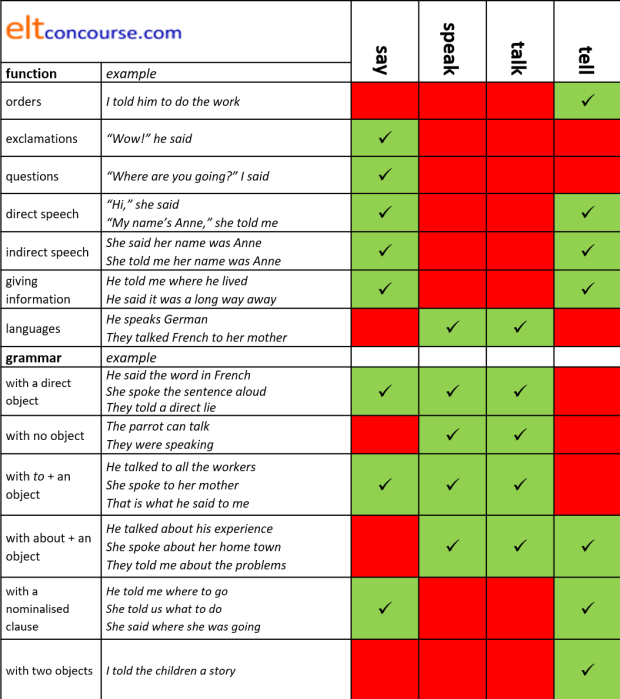

In summary, to be strict in our use of the term colligation with these verbs, we can say that at times they fall into the same colligation sets because they are sometimes found with similar syntactical properties. Usually, however, they do not themselves form a colligational set.

- The verb say is a colligate of the verbs shout,

call, scream etc. because it often enters syntactical

relationships in the same way:

He said / shouted / called / screamed, "Hello"

for example. - The verb speak is a colligate of the verbs

converse, natter and chat because it enters

syntactical relationships in the same way:

We spoke / conversed / nattered / chatted about the game

for example. - The verbs talk and speak are members of

the same colligational set in some meanings because they enter

syntactical relationships in the same way.

We talked / spoke about the problem

for example.

But, in other meanings they fall into different colligational sets as we see above. - The verb tell is a colligate of the verb relate

in some cases, of inform and notify in others

and of command and order in others because it

enters syntactical relationships in the same way:

She told / related / the story of her accident

She told / informed / notified me that that the train was cancelled

She told / commanded / ordered the children to be silent

In terms of certain prepositional and clause structures, the verbs also take on aspects of colligation sets insofar as, for example:

- Both say and tell can be followed by

finite clauses so, transitivity apart, are colligates and we

allow:

He said that he was angry

He told her he was angry

but not:

*He spoke that he was angry

or

*He talked that he was angry - Both talk and speak can be used with a

prepositional phrase referring to language type and are

colligates in this respect. We allow:

He talked in French to her

He spoke in French to her

but not:

*He said in French to her

*He told in French to her - The verb tell is an outlier, not a colligate of any

of the other verbs, because it is the only one which can take an

animate direct object so, while we allow:

She told me

we do not allow:

*She said me

*She talked me

or

*She spoke me - The verb tell is also an outlier, not a colligate

of any of the other verbs, because it is the only one which

cannot be used with to plus an object so, while we

allow:

He said it to me

She spoke to me

She talked to me

we do not allow:

*She told to me

In this case, the verbs say, speak and talk form a colligation set. - The verbs speak and talk are colligates in

terms of transitivity because they can both be intransitive so,

while we allow:

They spoke

and

They talked

we do not allow:

*They said

or

*They told - The verbs speak, talk and tell are

colligates in being used with a prepositional phrase with

about so we allow:

They talked about the job

They spoke about the job

and

They told me about the job

but not

*They said about the job

In answer to a student's question, this summary is suggested. Where verbs share the green cells, they are, in that sense, members of the same colligations. You can see, however, that the picture is by no means simple.

The analysis above, with the summary diagram, forms part of an answer to a language question on this site so, if you would like that and more as a PDF document, it is available here.

|

issues of di- and mono-transitivity

|

If something is a verb, is it transitive, intransitive, ditransitive and so on? For example:

- She gave / passed / handed / offered / lent / bequeathed

me the book

are all possible because the verbs can be ditransitive, working like give

BUT - *She presented / delivered / donated / handed over /

contributed me the book

are all prohibited because the verbs are resolutely monotransitive and any indirect object needs to be prepositional as in, e.g.

She presented me with the book

She contributed the book to the sale

She handed over the book to the librarian

etc. - Compare:

Mary wanted him to come to her party

Mary told him to come to her party

Superficially, these look like parallel forms but tell is a ditransitive verb and want is monotransitive. This means that we can have:

What Mary told him was to come to her party

but not:

*What Mary wanted him was to come to her party

and

Mary told him something

but not:

*Mary wanted him something

and

Mary told him that he should come to her party

but not

*Mary wanted him that he should come to her party

To explain this issue we need to look at how the sentences can be broken down.

Because want is rigidly monotransitive it can only have one object so we can analyse the sentence as:Subject Verb Direct object Mary wanted him to come to her party Mary wanted a birthday present

The verb tell, on the other hand, can be both mono and di-transitive so we can analyse the sentences like this:

There is no particular mystery here because clauses such as to come to her party, him to come to her party or that he should come to her party can be nominalised in the usual way and function as the object of a verb.Subject Verb Indirect object Direct object Mary told a lie Mary told him a lie Mary told him to come to her party Mary told him that he should come to her party

The issue is the type of transitivity.

A list of ditransitive verbs is available on this site, linked via the list of related guides at the end.

|

suggest, recommend, advise |

Because of their colligational characteristics, these three verbs cause a good deal of difficulty for learners of English. There are, naturally, semantic differences to get out of the way to start with:

- suggest has two meanings:

- to communicate something without stating it openly (intimate):

He suggested she was lying - to propose for consideration:

He suggested going for a walk

- to communicate something without stating it openly (intimate):

- recommend has the second sense of suggest but is

always positive:

She recommended a good hotel - advise has two meanings:

- to give counsel or special expert help:

We need an expert to advise us about this - to suggest a wise course of action:

I advise you to stay at The Grand

- to give counsel or special expert help:

As we shall see, the meanings sometimes determine the grammar the

words take. Colligation is complex.

For example:

We allow:

The doctor suggested that I give up smoking

The doctor suggested giving up smoking

The doctor recommended that I give up smoking

The doctor recommended giving up smoking

The doctor advised me to give up smoking

The doctor advised me that I give up smoking

The doctor advised giving up smoking

The doctor advised against smoking

The doctor advised me against smoking

But we do not allow:

*The doctor suggested me that I give up smoking

*The doctor suggested me giving up smoking

*The doctor suggested to give up smoking

*The doctor suggested against smoking

*The doctor recommended me that I give up smoking

*The doctor recommended me giving up smoking

*The doctor recommended to give up smoking

*The doctor recommended against smoking

*The doctor recommended to give up smoking

*The doctor advised me giving up smoking

The reasons stem from colligational characteristics of the verbs rather than any overarching grammatical or structural rules of the language. It works like this:

suggest and recommend

- Both these verbs mean put forward for consideration

or propose but recommend is always used with a

positive suggestion.

These colligating verbs can only have one object and the object can be- a simple noun phrase:

The doctor suggested some tablets

The doctor recommended some tablets - a verbal noun (gerund):

The doctor suggested taking some tablets

The doctor recommended taking some tablets - a nominalised subject plus verb phrase:

The doctor suggested that I (should) take some tablets

The doctor recommended that I (should) take some tablets - BUT not a to-infinitive

clause:

*The doctor suggested to take some tablets

*The doctor recommended to take some tablets - and not with a prepositional phrase:

*She suggested against the idea

*They recommended for the proposal

- a simple noun phrase:

- these verbs can also take a person as the noun phrase object

but the sense of put forward

is retained

The doctor suggested me (for the job)

The doctor recommended me (for the job)

advise

This verb has two connected meanings (it is polysemous) and its colligational features vary with the meanings.

- Meaning #1 = suggest or propose a course of action

- advise can take one

object in the same way as suggest and recommend.

This can be

- a verbal noun (gerund)

The doctor advised taking some tablets - a nominalised verb phrase

The doctor advised that I (should) take some tablets - a simple

inanimate noun phrase when it is clear

that the object of the advice is known and a person:

The doctor advised some tablets

The doctor advised more exercise. - a direct object (always human) followed by a

prepositional phrase using against:

The doctor advised me against the tablets - BUT not a to-infinitive

*The doctor advised to take some tablets

- a verbal noun (gerund)

- advise can take one

object in the same way as suggest and recommend.

This can be

- Meaning #2 = give advice or counsel

- advise can operate with this meaning with two

objects the first indirect and the second direct but the

indirect object must be a person (as is usual). When there is an

indirect object like this, the direct object can be

- a nominalised verb phrase

The doctor advised me that I should take some tablets - a to-infinitive clause:

The doctor advised me to take some tablets - BUT not a verbal noun (gerund)

*The doctor advised me taking some tablets - and not a noun phrase

*The doctor advised me some tablets

- a nominalised verb phrase

- advise can also operate with a single direct

object in this meaning:

The doctor advised me well

and in this case it does not carry the sense of put forward but retains the meaning of counsel or guide. - advise can also operate intransitively

providing there is a prepositional phrase adverbial:

The doctor advised against an operation

Again, the verb carries the sense of counsel, not put forward.

- advise can operate with this meaning with two

objects the first indirect and the second direct but the

indirect object must be a person (as is usual). When there is an

indirect object like this, the direct object can be

The above also forms the answer to a commonly asked language question so if you want it as a PDF document, it is available here.

|

verbs of sense, perception and mental processes |

Certain verbs types describing perception form colligates, in this case, sharing the use of -ing forms and bare infinitives. For example:

- I noticed him arriving

They saw him fall

Peter heard him singing

I smelt it burn

I smelt it burning

etc. - BUT verbs concerned with mental processes

form a different set of colligates.

I expected he would arrive late

*I expected him arriving late

I predicted he would arrive late

*I predicted him arriving late.

I hoped he would arrive early

*I hoped him arriving early.

I guessed he would arrive early

*I guessed him arriving early

With the set of colligates under 1., the structure is:

Subject (invariably animate) +

verb + object + non-finite verb form (bare

infinitive or -ing form)

With the set of colligates under 2., the structure is:

Subject (invariably animate) +

verb + finite clause with would

An oddity in this section is the verb expect which can

take the same structure as set 1. but uses the to-infinitive as in,

e.g.

I expected him to arrive late

|

nouns: sentence position |

Certain words

naturally occur more frequently in certain grammatical slots.

Hoey,

op cit., for example, notes that the word consequence very rarely occurs as the object of a clause or

a possessive verb so

- It produced the consequence that ...

and

It has the consequence that ...

are rare. - but, as the subject or complement, the word is very much

more frequent so expressions such as

The consequence was that ...

and

It is a consequence of ...

are very much more common.

Similar considerations apply to the words preference and use which will occur frequently as objects of clauses and possessive verbs:

- He expressed a preference for leaving early

He explained its use to me - She has a preference to leave early

They criticised its use as a classroom aid

but are rare as the subject of the verb phrase:

- A preference eventually emerged during the meeting

- The use was not allowed

both of which seem unusual to many speakers of English.

|

probable and likely |

- It's likely John will help me up

It's probable John will help me up

BUT - John will likely help me up

*John will probable help me up

In 1., the two words are synonyms with the same grammatical

characteristics but in 2., although the

meaning is the same, the grammar isn't. The words colligate

differently.

We can't make the

subject of the clause be the person identified in both cases but the

construction with the dummy it works for both words.

|

try and attempt |

- It's hard to move it but please try to

It's hard to move it but please attempt to

BUT - It's hard to move it but please try

*It's hard to move it but please attempt

The to complement is optional with try but obligatory with attempt.

|

ought to, should, let and allow |

- I oughtn't to leave him alone to go

vs.

*I oughtn't leave him alone - I shouldn't leave him alone

vs.

*I shouldn't to leave him alone - I allowed him to stay in the park

vs.

*I allowed him stay in the park - I let him stay

vs.

*I let him to stay

The to complement is obligatory with ought and allow but prohibited with let and should.

|

stop, cease, finish, complete |

- It stopped raining

It ceased raining

BUT - It ceased to rain

*It stopped to rain

cease may be followed by an

infinitive or an -ing form

but if stop is treated the same way the to

is interpretable as in order to.

The verb stop can also be transitive as in, e.g.:

I stopped the car

but cease cannot be used that way so:

*I ceased the car

is not available.

The use of the verbs stop, cease and finish is also determined by something called telicity which refers to whether an action is seen as having an end point, and is telic, or not, so is atelic. For example:

- I finished cooking at 5

- I ceased cooking at 5

- I stopped cooking at 5

In sentence 1. the sense is that the cooking was complete so the

verb is telic.

In sentences 2. and 3., however, both verbs imply a temporary end

point and suggest that the cooking would be resumed. In other

words, the verb finish is telic and the verbs stop

and cease can be atelic.

To complicate matters, the verb complete generally takes a noun

object rather than a non-finite verb so we allow, e.g.:

I completed the cooking at 5

I completed the meal at 5

I completed preparing the meal at 5

but

?I completed cooking at 5

is questionable at best.

In all cases, the verb is, like finish, telic.

|

want and wish |

- I want to know the truth

I wish to know the truth

BUT - I want the truth revealed

*I wish the truth revealed

wish does not permit a passive participle.

|

sick, poorly and unwell |

- The child was sick

The child was poorly

The child was unwell

The sick child

The poorly child

BUT - *The unwell child

Otherwise synonymous adjectives may have different characteristics in terms of attributive vs. predicative use.

|

nearly and almost |

- I nearly lost my temper

I almost lost my temper

I very nearly lost my temper

BUT - *I very almost lost my temper

The issue here is choice of modifier: almost cannot be modified with very.

|

as well, too and also |

- She does yoga as well

She does yoga, too

She does yoga also

She also does yoga

BUT - *She too does yoga

*She as well does yoga

Some words can have flexible word ordering; others are stricter.

|

conjunction vs. conjunct |

This is not the place to dwell on the differences between a

conjunct and a conjunction (for that, see the guide to adverbials linked in the list of related guides at the end). Briefly, however, there are words which join

ideas (coordinate and subordinate) in sentences and these are

conjunctions. Other words, which refer from sentence two back

to sentence one and contribute to a strong sense of cohesion are

conjuncts.

The grammar of the two word classes is significantly different even

though the meanings may be parallel. Two examples are enough

here but you can probably think of a range of other pairs which

function similarly:

- however and but

- The first of these is a conjunct expressing a contrast or an

adversative meaning and the second of these is a conjunction

expressing a very similar idea so we can have, e.g.:

I called for you at six. However, you had already left

and

I called for you at six but you had already left

and most people would consider these to express the same meaning.

If we try to swap the words around, we get non-English or a run-on sentence because they colligate differently:

*I called for you at six however you had already left

*I called for you at six. But you had already left. - though and although

- The words though and although are often presented to

learners as synonyms. Conceptually, they are but syntactically

they are not. The word though can be a conjunct or a

conjunction but although is only

a conjunction. We can accept, therefore:

The work was done on time. It was more expensive than I expected, though. (conjunct)

The work was done on time though it was more expensive than I expected (conjunction)

The work was done on time although it was more expensive than I expected (conjunction)

but not:

*The work was done on time. It was more expensive than I expected, although.

|

Colligation in the classroom |

Here are five implications

- Context

The existence of colligation simply adds even more weight to the need to present lexis in context so that the syntagmatic relationships between the target language, its collocational aspects and its colligational nature can be observed and practised. - Noticing

Just as it is possible, indeed helpful, to draw learners' attention to collocational patterns in texts, so we can draw their attention to colligational patterns. Something like this:

I let him go to the club although his mother had forbidden him to do so because his father always tolerated his visits.

or

I gave John the money to pass on to Mary but he lent Peter all of it. Peter donated it to the household expenses and it was duly delivered to the grocer. - Translation

In many circumstances, translation between English and the learners' first language(s) is a useful, awareness-raising technique and a classroom shortcut. However, if it is carried out without due understanding of colligational differences between the languages, it can be error inducing.

For example

I allowed him to go

and

I let him go

can both be translated in German the same way (Ich ließ ihn gehen) but the grammar in English is more complex and misunderstanding may result in

*I let him to go

or

*I allowed him go.

On the other hand, French handles the two verbs differently (Je lui ai permis d'aller and Je l'ai laissé aller, respectively) and without an understanding of word grammar, this could give rise to

*I allowed him for going

or

*I let him to go.

These are just two examples and, as may be imagined, colligational phenomena across languages are even less predictable and parallel than are collocational phenomena. - Transitivity and the passive voice

When a new verb arises in the classroom from a reading text, a listening text or by demand from the learners, it is important to be alert to its nature in terms of transitivity. We saw above that we allow:

I hid it

I hid

I concealed it

She owned the house

She possessed the house

She had a house

but not:

*I concealed

*The house was possessed (except in a rather spooky and different sense)

*The house was had by her

and these are all examples of how transitivity and / or passive formations work in English that are not likely to be parallel in other languages. - Dealing with error

As Hoey points out, colligational error can result in grammatically well-formed sentences which are, nevertheless, 'not English'.

When you are faced with such errors in your learners' production, looking out for the correct colligation in English is often fruitful.

| Related guides | |

| collocation | for a guide to a related area |

| adverbials | for a guide explaining conjuncts among much else |

| the passive voice | for more on colligational restrictions with passive constructions |

| ditransitive verbs | for a list with some notes of ditransitive verbs in English |

| tenses index | for a little more on telicity compared to perfective and imperfective verb uses |

| verb and clause types | for more on transitivity and other features of clause structure |

References:

Crystal, D, 2008, A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics,

Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Hoey, M, 2003, What's in a word?, Macmillan, MED Magazine,

Issue 10, August 2003