Relative pronoun clauses

|

DefinitionsThe dog which howled all night |

Here's a definition from Parrott who avers that relative clauses are:

complex structures which allow the speaker to express themselves

succinctly and fluently

(Parrott, 2000, p. 381)

They actually do rather more than that but it's a good working definition to begin with.

Relative pronoun clauses are usually said to be clauses starting with

who(m), that, which, whose defining or identifying the

noun they follow.

Their function is one of subordination to which there is

a guide on this site.

So, for example, in

The dog which howled all night and kept me awake

The noun, dog, is rendered unique among millions of dogs

because only this one howled and caused a sleepless night.

In this sentence, the relative clause, which howled all night and

kept me awake, is acting to modify the noun, dog, and that

makes it adjectival in function. For this reason, some analyses

will refer to these structures as post-nominal adjectival modifiers (Celce-Murcia

& Larsen-Freeman, 1999, p 571) or adjective clauses (Yule, 1998, p 240).

We'll stick with relative pronoun clause here because it is more

familiar but those two descriptors are equally valid.

The key point is that relative pronoun clauses modify and/or identify an

already specified noun phrase and in that sense they are akin to

adjectival phrases.

Some languages, see below, rely on using adjectival expressions alone to do this task, having nothing remotely like the English relative pronoun structures. For speakers from these language backgrounds, the concepts and meaning are, initially, at least, obscure.

If you are wondering why where, when and how are not

in the list above, the answer is that these words are analysed elsewhere

in the guide to relative adverbs.

Relative pronouns, as the name

implies, are words which stand for a noun, a gerund, a noun phrase or a

nominalised clause (i.e., different sorts of nouns).

If the word refers to why, where, when or how an action is carried out

or a state exists, it is an adverb, not a pronoun and does not belong

here.

That relative pronouns and relative adverbs appear to be related is not

in question but relative adverbs function differently and perform

different grammatical tasks. Relative adverbs cannot, for example, appear as

the objects or subjects of verbs (because they aren't nouns of any

sort). One relative adverb, how, cannot refer to a noun

at all.

As we shall shortly see, relative pronouns are distinguished by the

functions they perform in sentences, technically their relationship to

the arguments (most commonly subject, direct object, indirect object

etc.).

Understanding how to use them relies on being able to untangle

the grammatical functions of phrases and clauses in sentences.

|

|

|

Again, the terminology varies. Here, we will use defining and

non-defining because the terms are the most familiar but the three pairs

of ways to describe the fundamental types are synonymous.

Here are four sentences to compare:

- The Statue of Liberty, which stands in New York, is well known.

- The Statue of Liberty which stands in New York is well known.

- The statue of Gandhi which stands in Tavistock Square is well known.

- The statue of Gandhi, which stands in Tavistock Square, is well known.

Before you go on, decide which of those sentences you are happy to accept.

What's the difference in meaning between these pairs of sentences? Click here when you have an answer.

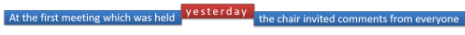

- At the first meeting, which was held yesterday, the chair invited comments from everyone.

- At the first meeting which was held yesterday the chair invited comments from everyone.

- The kids, who came with me, had lunch on the train.

- The kids who came with me had lunch on the train.

- Sentence 1

- contains a non-defining relative

clause. The fact that the meeting was held

yesterday is additional information which can be ignored

because the sentence makes sense without it.

We can put the relative clause in brackets with no change in meaning:

At the first meeting (which was held yesterday) the chair invited comments from everyone. - Sentence 2

-

contains a

defining relative clause.

We are only talking about the first meeting which was held yesterday.

Other meetings were held yesterday but we are only concerned with

the first of these. If we move the

constituents of the sentence around, we have to move the whole

prepositional phrase:

The chair invited comments from everyone at the first meeting which was held yesterday. - Sentence 3

- contains a non-defining relative clause. The only kids in question are those who came with me. All the kids had lunch on the train and the extra information that they came with me is additional (and it could appear in brackets, like this)

- Sentence 4

- contains a defining relative clause. There were other kids (who came alone or with someone else) who had no lunch / had lunch somewhere else. I only know that the kids who came with me had lunch.

In this guide, we are distinguishing between defining and non-defining relative clauses. These are often called restrictive and non-restrictive clauses respectively.

Now look again at the first four sentences concerning statues and decide what the issue was. Here's the comment:

| Sentence | Issue |

| The Statue of Liberty, which stands in New York, is well known. | The clause between the commas is simply adding information concerning the location of something known to us all. |

| The Statue of Liberty which stands in New York is well known. | There is only one such statue so to omit the commas would be wrong. You cannot define that which is unique. |

| The statue of Gandhi which stands in Tavistock Square is well known. | There are many statues of Gandhi around the world so to define a particular one by where it is is acceptable. |

| The statue of Gandhi, which stands in Tavistock Square, is well known. | This is also acceptable. Here we are talking about a statue of Gandhi but adding information to say where it is, not defining it. |

Try another slightly different

example:

In the following, why is it not possible to take out the commas in

the first sentence or to insert them in the second? Click

when you have an answer.

- The Nile, which runs through Egypt to the Mediterranean, is vital to the country’s prosperity.

- The man who asked me to marry him on that memorable evening is still my husband.

In Sentence 5, we know there is

only one Nile so we don't need to define it. In fact, defining

it by omitting the commas implies that there is another Nile river

somewhere. The subject of the verb is in the first case is

simply The Nile.

In Sentence 6, we need to identify

the complement of the verb is. The

complement of the verb is is not the man, it is the man who

asked me to marry him.

Defining (restrictive / identifying) relative pronoun clauses are by far the most common.

|

Meaning |

The difference between restrictive / defining and non-restrictive

/ non-defining relative clauses is not just a grammatical wrinkle in

English because the meaning the speaker / writer conveys differs

very significantly depending on which type of clause is used.

The key point is that defining clauses give required

information whereas non-defining clauses give additional

information.

The distinction is a familiar one concerning given and new

information.

For example, in these two sentences, we have a clear distinction in meaning:

- The woman, who arrived at the hotel this evening, has gone out

- The woman who arrived at the hotel this evening has gone out

In sentence a., both speaker and hearer are aware of the existence of

the woman and know to whom reference is being made. The

information about the hotel is new.

In sentence b., this is not the case and the speaker selects the grammar

accordingly because the necessary information to distinguish which woman

is being spoken of is needed for comprehension. The assumption in

sentence b. is that the hearer already knows about the woman and

that she arrived at the hotel. The only new information is that

she has gone out.

This is even clearer when we use names rather than common nouns.

Compare, for example:

- Margaret, who arrived at the hotel this evening, has gone out

- Margaret who arrived at the hotel this evening has gone out

In sentence c., the person referred to is known to both speaker and

hearer and the information about the hotel is peripheral but probably

new to the hearer (why else state it?).

Sentence d. is very strange and it is difficult to imagine it ever being

produced unless there are two Margarets to whom reference may be being

made and the speaker needs to disambiguate to refer only to one of them.

In this case, the speaker assumes that the hearer knows there are two

possible people called Margaret to whom reference is being made

and that one of them arrived at the hotel and one did not.

One way to explain this distinction to learners whose languages may

not make any distinction at all between the two types of clause is to

consider a simple attributive adjective phrase in a sentence such as:

The hardworking students passed the examination

which is ambiguous because this may mean either:

The students who worked hard passed the examination

(and other students, less hardworking, did not)

or

The students, who worked hard, passed the examination

(all of them)

It is difficult to signal what is meant by intonation n the adjective

phrase, although stressing the adjective strongly might show that a

restrictive meaning is intended. In the written form, no

punctuation changes can be made to show what is meant, although one

could resort to underlining or other emphasis markers.

The two relative pronoun clauses are much more easily distinguished by

intonation and punctuation signals. See below.

|

Next question |

If you use phrases like all of which, either of whom, both of which, the majority of whom, none of which, etc., would you normally expect to separate the clause off with commas or not? Click here when you have an answer.

Expressions like some

of, many of + the relative

pronoun often introduce non-defining clauses so we get, e.g.,

The children,

all of whom had lunch in the park, went on to visit the museum.

The men, either of whom could

have been her brother, arrived very late.

The houses, the majority of which are Victorian, line both sides of

the street.

So, yes, we need the commas because we do not define the noun

with these expressions, we add information to it.

|

Pronunciation |

In written English, commas are used to distinguish the two types. How does this work in spoken English? Click here when you have an answer.

In

written English, commas are used in non-defining

clauses only. In spoken English, the distinction is in the phrasing

and tone or key.

Try saying sentences 1, 2, 3 and 4 aloud.

You will find that when you say a non-defining relative clause, two

things happen:

- You insert a slight pause before the relative pronoun (and often, after the relative clause itself).

- Your voice tone lowers and you may speak more quickly and quietly when you say the relative clause.

It looks like this:

- Non-defining / non-restricted relative clause:

-

- The voice tone falls on the relative clause and it is usually spoken

more quickly with small pauses before and after it.

In this case, the prepositional-phrase adverbial which pre-modifies the verb invited is just At the first meeting

- Defining / restricted relative clause:

-

- The voice tone rises towards the end of the relative clause and the

key information may be spoken more slowly and emphatically.

If the key information concerns the fact that this was the first meeting among many held yesterday, the pitch across the sentence may look rather different but still be distinguishable as a defining relative clause:

- In both latter cases, the adverbial phrase pre-modifying the verb invited is At the first meeting which was held yesterday.

|

Memory test |

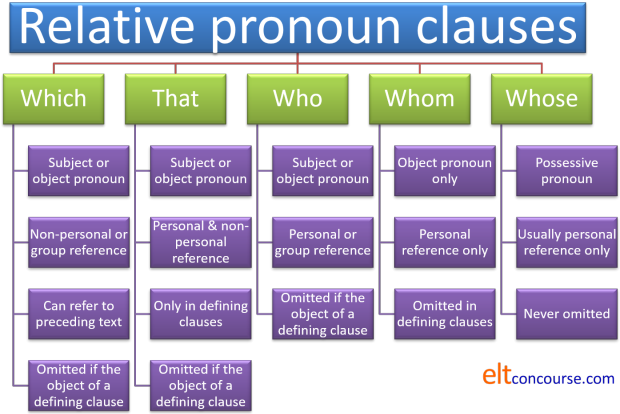

There are five relative pronouns in English, listed at the top of

this page – what were they?

Click here

when you have written them down.

| pronoun | use | examples |

| who | subject or object pronoun for people | The students who had the party are now living over there. |

| which | subject or object pronoun for animals and things |

|

| referring to a whole clause or previously mentioned idea (only which can do this) | They fell in love and got married the following month which surprised everyone. | |

| whom | object pronoun only for people (especially in non-defining relative clauses and formal) | Melissa, whom I met at the party, invited me. |

| whose | possession (a genitive pronoun) | Did you know the man whose sister married the vicar? |

| that | subject or object pronoun for people, animals and things in defining relative clauses (who or which are also possible) |

|

|

Subject or Object? |

It's important to know whether the relative pronoun is acting as the

subject or the object of the verb. What's it doing in the

following examples? Look at the

underlined clauses and decide if they refer to the subject or

object of the verb phrase.

Click when you have an answer.

- The man who bought the tickets really is just being generous

- The tickets, which hopefully will allow us entry, are very welcome

- The man that we thanked seemed genuinely surprised

- The tickets which he bought were quite expensive

- Only the senior doorman, who we gave the tickets to, noticed that they were fakes

Here are the answers:

-

The man who bought the tickets really is just being generous

– subject – the pronoun who is followed by

verb phrase (bought the tickets)

We can re-phrase the first part of the sentence as

The man bought the tickets (Subject – Verb – Object) - The tickets, which hopefully will allow us entry, are very

welcome – subject again – which is followed by the

verb phrase hopefully will allow us

We can re-phrase the first part of the sentence as

The tickets will hopefully allow us entry (Subject – Verb – Object) - The man that we thanked seemed genuinely surprised – object

– that is the object of we thanked

We can re-phrase the first part of the sentence as

We thanked the man (Subject – Verb – Object) - The tickets which he bought were quite expensive –

object – which

is the object of he bought

We can re-phrase the first part of the sentence as

He bought the tickets (Subject – Verb – Object) - Only

the senior doorman, who we gave the tickets to, noticed

that they were fakes – indirect object after preposition to

We can re-phrase the first part of the sentence as

We gave the tickets to the senior doorman (Subject – Verb – Direct Object – Indirect Object)

A simple rule to tell students is:

If the relative pronoun is followed

directly by a verb phrase, it’s the

subject.

So, in

The man who just bought the car

the

relative pronoun, who, is followed directly by the verb

phrase, just bought. This means that the relative

pronoun stands for the subject of the verb.

If the pronoun is not followed by a verb phrase (but by a noun

phrase or pronoun) it is the object.

So, in

The book which she bought was a first

edition

the relative pronoun, which, is followed

by a pronoun, she, so it cannot be the subject of the

verb. The relative pronoun stands for the object of the

verb and can be, and routinely is, omitted.

|

Omitting the pronoun |

In which of sentences 7 – 11 can you omit the relative

pronoun?

Why (not)?

Here they are again:

- The man who bought the tickets really is just being generous

- The tickets, which hopefully will allow us entry, are very welcome

- The man that we thanked seemed genuinely surprised

- The tickets which he bought were quite expensive

- Only the senior doorman, who we gave the tickets to, noticed that they were fakes

Click here when you have an answer.

In Sentences 9 and 10

only, we can omit the relative

pronoun because it is the object of a defining relative clause.

We can have, therefore

The man we thanked

or

The man that we

thanked

but we can't have

*The man bought the tickets really

is just being generous

Why?

Rule 1 is: Subject relative pronouns must

always be used.

In sentence 7, the relative pronoun is the subject so the

relative pronoun must be retained.

In Sentences 7 and 8 the relative pronoun is

the subject (followed by verb phrase) in 9, 10

and 11 it’s the object (followed by pronoun or noun phrase).

We can have

The man who bought the

tickets really is just being generous

but not

*The man bought the tickets really

is just being generous

and

The tickets, which hopefully will

allow us entry, are very welcome

but not

*The tickets, hopefully will allow

us entry, are very welcome

and

The man we thanked seemed

genuinely surprised

and

The man we that

thanked seemed genuinely surprised

and

The tickets he bought

were quite expensive

and

The tickets which

he bought were quite expensive

and

Only the senior doorman, who we

gave the tickets to, noticed that they were fakes

but not

*Only the senior doorman, we gave

the tickets to, noticed that they were fakes

Rule 2 is: Object pronouns can be dropped but

only in defining relative

clauses.

Sentence 10 is a defining relative clause so it's

OK to leave out the relative pronoun. Sentence 11 is

non-defining so the relative can't be left out.

The reason for this lies in the meaning that the two sorts of

clauses signal. We saw above that non-defining or

non-restrictive relative clauses add new information but

defining or restrictive clauses rely on the the speaker / writer

and the hearer / reader sharing the information necessary to

understand what is the subject of the clause.

In order to signal the new information contained in a

non-defining clauses, the pronoun is necessary because without

it the hearer / reader cannot know to what the new information

refers.

Is it possible to omit whose?

No.

We can have:

The man whose tickets we stole

but not

*The man tickets we stole

|

Using that |

| The man that she met |

Here are the example sentences again with some more at the end:

- At the first meeting, which was held yesterday, the chair invited comments from everyone.

- At the first meeting which was held yesterday the chair invited comments from everyone.

- The kids, who came with me, had lunch on the train.

- The kids who came with me had lunch on the train.

- The Nile, which runs through Egypt to the Mediterranean, is vital to the country’s prosperity.

- The man who asked me to marry him on that memorable evening is still my husband.

- The man who bought the tickets really is just being generous

- The tickets, which hopefully will allow us entry, are very welcome

- The man that we thanked seemed genuinely surprised

- The tickets which he bought were quite expensive

- Only the senior doorman, who we gave the tickets to, noticed that they were fakes

- The man whom we met turned out to be his brother.

- The man who met us was his brother.

- The table which I wanted had been sold.

- The table which cost too much was the only one left.

In which of these sentences 1 – 15 can that be used as the

relative pronoun instead of who(m) or which? What's

the rule?

Click

here when you have an answer.

In sentences

2, 4, 6, 7, 9 (obviously), 10, 12, 13, 14 and 15

What’s the rule?

The pronoun that can

only be used in defining relative clauses and then it’s more informal.

By the way, there is a structure in English using that which

looks a bit like a relative clause but isn't and it will confuse

learners if you introduce it alongside proper relative pronoun clauses.

It is, for example:

It was because I felt ill that I had to go to bed

The word that is not, in this case a pronoun at all, arguably,

because there is no noun for it to represent.

It is better analysed as a cleft sentence, to which there is a guide on

this site linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Prepositions in relative clauses |

The following sentences contain prepositions. How are these

significant?

What is the rule for dealing with prepositions in relatives? Click

here

when you have an answer.

- This is the car in which he arrived.

- This is the car which he arrived in.

- This is the car he arrived in.

- This is the person with whom he arrived.

- This is the person who(m) he arrived with.

- This is the person he arrived with.

Rule 1: the relative pronoun is usually the object so

it

can often be omitted, leaving only the preposition in place.

Rule 2: the preposition is moved to the end in

informal language.

|

Reduced relative clauses |

Consider these four sentences:

- The woman in the garden is my mother.

- The woman outside is my mother

- The kid acting the fool is my sister.

- The woman, an expert on gardening, is helping my mother

When is it possible to omit both the relative pronoun and the verb be? Click here when you have an answer.

Rule 1: if the verb be

is

followed by a prepositional or adverbial clause

Rule 2: if the verb is in the progressive

aspect

Rule 3: if the noun phrases are co-referential

There are four sorts of reduced relative clauses exemplified above:

Sentence 22. is a prepositional reduced

relative clause and can be expressed as:

The woman who is in the garden is my

mother.

Sentence 23. is an adverbial reduced

relative clause and can be expressed as

The woman who is outside is my mother

Sentence 24. is a participle reduced relative

clause and can be expressed as:

The kid who is acting the fool is my sister.

Sentence 25. is an appositive reduced relative

clause (which means that the two noun phrases are co-referential

– they refer to the same person). This can be expressed

as:

The woman, who is an expert on gardening, is helping my

mother

Prepositional, adverbial and participial relative clauses are

defining relative clauses.

Appositive relative clauses can only be non-defining

because we cannot define the subject twice.

In formal language, the commas are often replaced with brackets

in appositive clauses.

|

Nominal or fused relative clauses |

In the analysis above, all the examples contain both the

relative pronoun and what is known as its antecedent (i.e., the

noun the relative pronoun refers to). So, for example, in

That's the man who stole my bicycle

it is clear that the man and who refer to

the same person. So, the man is the antecedent of

the pronoun who.

and in

The tickets which we sold to my brother

the antecedent of the pronoun which is the tickets.

Frequently, however, the antecedent is either understood or

simply absent. This is why clauses of this type are

sometimes called fused relative clauses (because the antecedent

and the pronoun are combined) or nominal relative clauses

(because the whole clause is acting as a noun).

Here are some examples:

As you see, nominalised or fused relative clauses fill the same grammatical slots as noun phrases (hence the name).

With nominal relative clauses certain relative pronouns are used:

- what is the most common

- who and which are also commonly used as object nominalised clauses

- the -ever series of pronouns are also frequent

Warning: some sources will include formulations such as

How(ever) you do it is your business

Whenever he comes is OK with me

but these are, in fact, relative adverbs, not relative pronouns

(and the subject of a different guide linked in the list of related guides at the end).

If the word refers to when, how or why, it is not a relative

pronoun, it's a relative adverb and they function significantly

differently. To mix them up, and hence confuse your

learners, is unwise.

Some wh- and that-clauses occur in what are known as cleft

sentences and there is guide to these on this site linked in the list of related guides at the end.

Unlike other nominal clauses, nominal relative clauses can act as the

indirect object so we allow, for example:

I'll give whoever asks a new book.

There are also structures called free relative clauses and those, too, are considered in the guide to relative adverbs because they share some characteristics. As you will see, if you go to that guide, this site takes the view that nominalisation is a better way to think about such things.

|

The position of the relative clause |

As saw in many of the examples in the guide so far, relative

pronoun clauses can occur in mid-position in a sentence, with or

without the object pronoun. For example:

The man (whom)

you met was my boss

The book (which / that) you took

was mine.

The person who sold me the car

has left the country

etc.

Relative pronoun clauses are also frequently found in the final

position in sentences because they typically introduce new information

(and that is a common phenomenon in English called end focus).

The antecedent is commonly an indefinite pronoun such as one of the

any- or some- series or an indefinite noun phrase such as

a person, a child, a thing, a tool etc. For example:

I’m looking for someone

who can help me write a website

We need something which can act as

a counterbalance

Can you find us a local who can

show us the way?

I don't have the tool that will do

the job

Is that the man whose father is

an MP?

etc.

This position is common with an existential there is / there are

structure. For example:

Is there anyone here

who can help me?

There is something over there that

looks like a snake

There are some things

(that) I always forget to pack

etc.

By the nature of such sentences, the relative pronoun is often the

subject and cannot, therefore, be omitted.

Non-defining relative clauses almost always occur in mid-position so

we can have:

My sister, who lives in America, may be able to

help you with that

but not:

*My sister may be able to help you with that, who

lives in America

|

Stacking pronoun relative clauses |

Relative pronouns clauses can also be stacked in the final

position so we can have, for example:

That is the book I got from the library which I like but that

you hate

In theory, there is no limit to how many relative pronoun

clauses can be stacked in this way but native speakers stop at

two or three.

This is less common in mid-position because of the cognitive overload

produced by trying say (and understand) something like:

Have you given the food which I cooked and that you hated but

which the guests enjoyed to the dog?

Non-defining clauses, probably up to a maximum of two, can be

stacked in mid-position. For example:

His brother, who lives in France and who speaks French, may

be able to translate that.

It is possible to have more than two of these, providing they are

short enough so, e.g.:

His brother, who lives in France, speaks French, can be

contacted by email and is usually helpful, may be able to translate that

is possible but that's about the limit of the cognitive load with which

speakers and listeners can cope.

|

Sentence relative clauses |

| ... which shocked me |

There is an odd form of relative clause in which it is not

possible to identify an antecedent noun phrase because the

reference is not to a particular person or object but to the

whole of a preceding sentence (or even a longer text). The

name for this varies in the literature but here we will refer to

them as sentence relative clauses although you

may find them called comment clauses and a number of other

things.

The only one of the five pronouns which can function this way is

which.

Here are some examples:

They fell in love and got married,

which astonished everyone they knew.

After the rain, the garden flourished,

which was no surprise.

Once we had had the meeting, matters improved,

which was welcome.

These clauses are generally separated from the antecedent text by

commas because they are, in fact, non-defining, in the sense that the

preceding text can sensibly stand alone.

They always follow the text to which they refer.

It is not possible to omit the pronoun.

|

Other languages |

Relative clauses in English come after the noun to which they

refer. The reason for this has to do with how elements are

ordered in English in terms of what is known as heaviness.

A heavy element of a clause is more grammatically and lexically

complex than a light one. For example, modifying a noun

with a determiner or simple adjective as in:

that car

a car

the car

three cars

red car

is a very light way to do so and English prefers light elements

to precede the noun so we do not get

car that

cars a

car the

cars three

car red

and so on.

This is not the case, incidentally, in a range of other

languages, including Yoruba and many African languages as well

as Thai and many other South-East Asian languages.

However, modification with a complex prepositional phrase will

normally follow the noun because it is a heavier element than a

single determiner or adjective so we have, e.g.:

the car over there with the broken

headlight

not

the over there with the broken headlight

car.

Relative clauses are just about the most complex way in which

noun phrases can be modified in English so it is unsurprising

that the clauses follow the noun they modify or refer to.

That is not a universal tendency of all languages but it is one

shared with most European languages.

The ways in which other languages form relative clauses is

very varied and first-language interference errors are common

when learners are acquiring the system in English.

Here's brief run-down of the most important differences.

It behoves you to find out how your learners' first language(s)

handle the area so you are prepared for the interference issues

and can focus on salient differences. If you are a native

or very competent speaker of your learners' first language(s),

this just requires a little thought. In other

circumstances, it requires a little research.

- who vs. which

Many languages, including but not limited to:

Dutch, Albanian, Scandinavian languages (including Finnish, this time, and Icelandic), German (in which relative pronouns closely parallel the form of the definite article), Spanish, French, Italian, Malay / Indonesian, Latvian, Maltese, Portuguese, Greek, Russian, Polish (and other Slavic languages including Slovak, Czech and Slovene etc.), Farsi and Thai

do not distinguish between a pronoun referring to people and one referring to inanimate objects and animals. In most languages, therefore, there is no pronoun distinction between

The wind which came in

and

The man who came in

so errors such as

*That's the man which I saw

*That's the table who he bought in France

etc. are frequent and have to be handled by making sure that the distinctions in English between who and which are very clear.

Speakers of these languages, aware that English is different in this respect, may be tempted to play safe and overuse that in grammatical environments where it is not allowable (i.e., in non-defining or non-restricted clauses). Errors such as:

*The Eiger, that is in The Alps, is a beautiful mountain

or

*The bus, that I take every morning, was very late today

will occur.

Additionally, that is often unacceptably informal, especially in writing, and that leads to stylistic error.

Finally, some of these languages use that and what interchangeably and that produces errors like

*That's the man what he said would come

*The wind what came in

*The man what came to the meeting

etc. - Non-parallel structures

Even languages which sometimes distinguish between pronouns for people and things do so in ways which do not parallel English at all.

In French, for example, different pronouns are used depending on whether the object or the subject is the reference (que and qui respectively) but both can be used for animate and inanimate nouns.

Italian uses different pronouns depending on whether the noun is followed by a preposition or not (cui and che respectively).

Portuguese has a single relative pronoun (que) which can refer to people or things but this changes to quem when preceded by a preposition. The word quem is only used to refer to people and means who or whom.

All of these differences can lead to interlingual errors because of temptation to assume that differences like these are paralleled in English.

A further non-parallel aspect is the use of which as a sentence relative clause to refer to a preceding text rather than an identifiable antecedent noun phrase. Most languages will not use a pronoun in this way, preferring something like ... and that + the comment or using an equivalent of what. - Omitting the pronoun

Most languages which use relative pronouns as subordinators do not allow the pronoun to be omitted and, apart from causing speakers to sound unnaturally formal with sentences such as

The book which I read explains it well

instead of the much more natural

The book I read explains it well

this also presents comprehension difficulties because learners from these backgrounds will have problems understanding

Is she the woman you spoke to?

or

That's the program you should run

because there are no obvious pronoun clues to what the object of the verb really is.

Languages which do not allow the pronoun omission are in the majority and include most of those listed in point 1, above.

The omission of the pronoun in English, incidentally, causes serious problems for machine translations for the same reason that comprehension issues arise. - Restricted and non-restricted uses

A range of languages, including Russian, German, Dutch and Polish, do not distinguish between restricted (defining) clauses and non-restricted (non-defining) clauses and that can cause punctuation, pronunciation and comprehension errors. In German, for example, all relative clauses are separated by commas, not just non-defining clauses as in English.

For speakers of other languages, in which the comma is used to separate sense groups rather than represent pausing, similar issues arise. - Concord

Most languages (including American varieties of English) are strict about concord and will strive to make verb and pronoun forms match the number and characteristics of the subject. English is sloppier in this respect and, depending on their notion about the nature of the subject, English speakers can accept, for example:

The group who were asked to work on the project

and

The group which was asked to work on the project

but will not allow

*The group which were asked to work on the project

or

*The group who was asked to work on the project

This will lead to some error because most learners will assume that English has the same grammatical regard for concord that their languages exhibit.

Other concord errors will occur, such as:

*The range of students which was accepted for a place at the university

which follows a grammatical rule (range is non-animate and singular and so should be followed by which and a singular verb form) but is unacceptable to most English speakers who would prefer:

The range of students who were accepted for a place at the university

These are examples of issues with notional and proximity concord respectively in English. For more on concord, follow the link below. - Absence of relative pronouns and clauses

You will search in vain for mention of relative pronouns in the grammars of many languages, including Turkish (usually), Korean, Tamil and Japanese, for the simple reason that these languages do not use them at all and no closely equivalent structures exist.

In most, the meaning is expressed either through compound adjectives, so we get:

*The by the river house

instead of

The house (which is) by the river

or by participle clauses so we get, e.g.:

*My friend living in America invited me to visit him

instead of

My friend who lives in America invited me to visit him

Some of these language, Turkish being an obvious example, do have a structure similar to a relative clause but the language uses non-finite forms rather than finite ones which English prefers. So, for example, a Turkish speaker with have little difficulty understanding or producing:

The car sitting in front of the house is his

but will not naturally produce and may have difficulty understanding

The car which broke down is in front of the house

and may attempt something like:

*The car breaking down is in front of the house - Resisting subordination

South Asian languages in particular resist subordination altogether, preferring other ways to express the fact that one part of a sentence depends on the understanding of another, and speakers of these languages (which include many in the subcontinent such as Hindi and Urdu) may have difficulty seeing the reason for relative clauses at all and struggle with both the forms and the whole concept of subordination in general. - Clause ordering

Finally, in Chinese languages, there are parallel structures but in these languages, the relative clause precedes rather than follows the noun phrase and that can produce errors such as:

Who is in England my friend wrote to me

Additionally, the pronoun may routinely be omitted regardless of the grammatical function it performs and that leads to errors such

*The man gave me the money was very friendly

This will also affect languages which use adjectival phrases or participle clauses to express the concepts (see point 6) because these structures also precede the noun and they may produce errors such as

*The parking the car woman ...

instead of

The woman (who is) parking the car

or

*The book buying the man is very expensive

instead of

The book (which) the man is buying / bought is very expensive

The distinction between the times when one can and cannot omit the pronoun and the ordering of the clauses need careful work.

|

Teaching relative pronoun clauses |

If you have been following up to now, you will know that this is not a simple system in English and the restrictions, as we saw above, are important. In particular, we (and, eventually, our learners) need to be aware of:

- when the pronoun can be omitted

- when the pronoun that can be used

- where the clause comes in the sentence

- which pronoun to select

- when the clauses can be reduced or nominalised

And these are just some of the issues you need to know about

and analyse before you can begin to tackle the area.

For this reason, careful selection of model texts or other

presentation texts is very important.

If the text you

select contains multiple examples of relative pronouns as

subjects, as objects, including that, reduced, with

omitted pronouns, in nominalised clauses and so on you are

asking for trouble. This will be compounded if you also

fail to distinguish between relative pronouns and relative

adverbs. For examples of the horrible, confusing mishmash

that doing so produces, search the web for lessons in the area. Alternatively, pick up any of a range of classroom coursebooks

whose authors have neglected to do the research.

At lower levels in particular, you need to focus very

carefully, introducing, say, only defining relative clauses

using who and which as subject pronouns in

model sentences such as

He is the student who asks lots of questions

or

That is the car which sat outside my house all night

Getting lower-level learners to form such sentences from:

He is the student

He asks lots of questions

or

That is the car

It sat outside my house all night

is a good beginning but it can't stop there, of course.

|

The window: a neglected classroom aid |

A quickly set up exercise to practise relative pronoun clauses

is to get your learners to look out of the classroom window and

tell you what they see. With a bit of priming and nudging from

you, that can elicit comments such as:

I can see a car which is parked illegally

There is a traffic warden who is putting a ticket on it.

The people whose car it is will be really upset

etc.

Clearly, this can't be done until the forms have been presented and

practised a little but it works well.

|

The learners: another neglected classroom aid |

Using your learners' own experiences (their internal world) can also be

productive and it is not hard to set up practice routines to evince

statements like:

We went on holiday to New York last year which I

found fascinating.

We have a room in the house which we only use for guests.

I remember a great teacher who really inspired his students.

etc.

It's up to you to limit and elicit the correct pronouns.

A semi-controlled practice idea is simple to get the learners to say

something true about three other people in the room (including you, if

you like) and three things they know about. That can evince

statements such as:

Paul is the guy who always knows the right answer.

Mary is the person who sits near the door

This is the coat Mary wore this morning

That's the pen Arthur stole

and so on.

It's a personalised and engaging exercise and, so the theory goes, makes

the structures memorable.

|

The students' mementos: another neglected classroom aid |

An associated idea is ask the learners to bring in half a

dozen favourite photographs or souvenirs and get them to explain

what they are of or where they came from. That can evince

language such as

It's a bag I bought in Tunisia

It's a photograph I took in Russia

The girl in the blue hat is my sister

and so on.

This works particularly well for practising the omission of the

pronoun because, by their nature, the items are generally the

objects of defining relative clauses.

The next step is to introduce the range (excluding that

for which special rules apply) until the learners can construct

acceptable subordinating clauses using which, who(m)

and whose.

Then it's time to focus on when the pronouns can be omitted

(restricted to defining clauses where the object is denoted by

the pronoun, and excluding whose).

Finally, the range of reduced clauses can be tackled along

with nominalised or fused relative clauses. That can be done

alongside consideration of wh- question forms because

the structures are more or less parallel:

I don't know what to wear

is not far removed grammatically from:

Do you know what to wear?

and

Do you know who arrived late?

because both have a nominalised wh-clauses as the

object of the verbs.

Summary

Here's a brief cut-out-and-keep summary of the area:

| Related guides | |

| relative adverbs | for more on another form of relative clause using adverbs |

| wh- questions | for an area allied to the use of nominalised relative clauses |

| cleft sentences | for more on how wh- clauses are used in English |

| concord | for more on notional and proximity concord |

| subordination | for more on other ways to make ideas depend on others |

Click for a test in this area.

References:

Campbell, GL, 1995, Concise Compendium of the World's Languages, London: Routledge

Celce-Murcia, M, Larsen-Freeman, D, 1999, The Grammar Book – An ESL/EFL Teacher’s Course 2nd ed., Boston: Heinle

Dryer, MS and Haspelmath, M. (eds.), 2013, The World Atlas of Language Structures Online, Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Parrott, M, 2000, Grammar for English Language Teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Swan, M and Smith, B, 2001, Learner English, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Yule, G, 1998, Explaining English Grammar, Oxford: Oxford University Press