Cognates and false friends

What are cognate words?

Cognates are words which have the same origin but exist in more than

one language.

You may encounter the word paronym to refer to cognates

but we'll stick with the usual term.

For example, the English word beer and the German word

Bier both come from the same root. One theory is that the

words come from the Latin word biber [a drink] and another

theory is that the words come from a very early German word for

barley. It really doesn't matter, even if it is quite

interesting. What is important is that the words

have the same root and refer to the same thing. This, of course,

makes it easy for English speakers to learn the German word and vice

versa. The pronunciation, in both languages, is nearly

identical although in English the final /r/ sound is usually droppeed.

However, there is also an English word bier which refers to the

support for a coffin and is unconnected to the German word Bier.

(The translation of the English bier in German is die

Bahre and the words are cognates both coming from the same root and

connected to the verb bear.) The words bier in

English and Bier in German are not cognates, although they look

similar.

Words may be cognates in a range of languages but the meanings can drift apart over the centuries to the point at which the connection is hard to see unless you have a good etymological dictionary to hand. For example, the English word clock (timepiece) is cognate with the German Glocke and the French cloche (both meaning bell) and the connection is clear but the words have diverged in meaning.

|

What cognates are not |

Out here in cyberspace, there is a good deal of uninformed assertion, error and confusion about this matter. Some careless, some ignorant and, just possibly, some deliberate.

Whatever you may read on the web, cognates are not:

- words which exists in the same language, with

the same root but which mean different things.

For example, in English, the words skirt and shirt both derive from the same word (the Old English scyrte) but they are not cognates. The technical term is a doublet. They derive from the same original source word (14th century, probably from Old Norse) by have drifted apart in meaning. - words which are imported into one language from another.

Partly for historical reasons, there are many hundreds of these in English taken from a variety of languages.

For example, from the West African language Hausa, English has borrowed bogus, from Arabic, there is a huge range from admiral to zenith and zero, from Hindi, English has borrowed another large number, from avatar to veranda and from European languages there are many thousands more which began as borrowings but are now not recognised as such because the words are embedded in the language.

Words may come from other languages via an intermediary language so a word borrowed from Arabic into Spanish (a common event) may then be borrowed again by English from Spanish.

Such words can make it slightly easier for speakers of some languages to learn some words in English but the words are not cognates, they are, technically, loan words.

There comes a time, of course, when what was a borrowing or loan word is no longer recognised as such. For example, the estimate is that around 10,000 words entered English from Norman French from the mid-11th to the early 14th centuries and a further 7000 or so came from Parisian French during The Renaissance. None of these words is now considered a borrowing because they are an accepted and unremarkable part of the English language. Their existence does result in cognate words in both languages (and other Romance languages such as Spanish, Italian and Romanian). Some of these words have retained the same meanings in English and another language and are helpful cognates, easy to understand and remember, but some have drifted apart and now constitute false friends. - words which look the same but have different

origins.

For example, the German word Gift [poison] and the English word gift [present] may look the same but they are not closely connected and the English word hell (Hades) looks and sounds the same as the German word hell (light coloured) but they derive from wholly different roots. Equally, the Japanese word for occur happens to be okoru but they, too, derive from very different sources. The English word kitten, looks like the Tagalog word kuting and they both mean the same thing but are wholly unconnected. Coincidences happen.

Technically, these are called false cognates, not, please, false friends.

For a little more help in disentangling the terms, there is a language-question answer here which also considers a separate area known as pseudo-Anglicisms.

|

True and false friends |

|

True friends help |

It is sometimes difficult (and rarely necessary) to distinguish

between a loan word and a cognate derived from the same source.

Indeed, it is difficult to identify the point at which a loan word

ceases to be a borrowing and becomes part of the language as we saw

above in the case of French.

For example, in Modern English we have many words derived from Latin

directly but we also have words imported from Norman French which in

turn were derived from Latin. Most people would now call the words

cognates, rather than loan words, whatever their route into English.

These are true friends to learners because the words not only look

much the same they mean much the same. They make

reading comprehension, in particular, much easier.

The following lists could be extended very greatly, of course. They are examples only.

Latinate words in English and some Romance languages:

| English | Spanish | Italian | French | Portuguese | Romanian |

| administer | administrar | amministrare | administrer | administrar | administra |

| operation | operación | operazione | opération | operação | operație |

| expression | expresión | espressione | expression | expressão | expresie |

| communication | comunicación | comunicazione | communication | comunicação | comunicare |

Right across Europe a number of words derived from Greek will also be familiar. Greek, too, is often the source of Latin words, incidentally. In the following Italian is the only Romance language (i.e., derived ultimately from Latin) but the words will be similar in others (see last table).

| English | Greek | Polish | Italian | German | Danish |

| democracy | δημοκρατία [deemokratia] |

demokracja | democrazia | Demokratie | demokrati |

| athletics | αθλητισμός [athleetikos] |

atletyka | atletica | Athletik | atletik |

| theatre | θέατρο [the-atro] |

teatr | teatro | Theater | teater |

| mathematics | μαθηματικά [matheematika] |

matematyka | matematica | Mathematik | matematik |

Greek still, of course, often forms the basis for coining new words, especially, in academic (ακαδημαϊκός [akademeyikos]) areas.

Among Germanic languages

(such as English and most Scandinavian languages) there are also a number of commonalities but they are not usually as

consistent as the ones above. We get, for example, the English

noun cook as Koch (German), kok (Dutch and

Danish), kokk (Norwegian) etc.

We can also see cognate words across languages which share an ancestor.

For example, the names of days of the week in Germanic, Slavic and

Romance languages are closely related within their groups (with a few

oddities):

| Germanic languages | Slavic languages | Romance languages | ||||||

| English | German | Swedish | Polish | Czech | Slovak | French | Spanish | Italian |

| Sunday | Sonntag | söndag | niedziela | neděle | nedeľa | dimanche | domingo | domenica |

| Monday | Montag | måndag | poniedziałek | pondělí | pondelok | lundi | lunes | lunedi |

| Tuesday | Dienstag | tisdag | wtorek | úterý | utorok | mardi | martes | martedì |

| Wednesday | Mittwoch | onsdag | środa | středa | streda | mercredi | miércoles | mercoledì |

| Thursday | Donnerstag | torsdag | czwartek | čtvrtek | štvrtok | jeudi | jueves | giovedi |

| Friday | Freitag | fredag | piątek | pátek | piatok | vendredi | viernes | venerdì |

| Saturday | Samstag | lördag | sobota | sobota | sobota | samedi | sábado | sabato |

Numbers, of course, show similar patterns and are noticeably similar even between languages only distantly related with some numbers (such as six and seven) being clearly related across all nine languages:

| Germanic languages | Slavic languages | Romance languages | ||||||

| English | German | Swedish | Polish | Czech | Slovak | French | Spanish | Italian |

| one | eins | en | jeden | jeden | jedna | un | uno | uno |

| two | zwei | två | dwa | dva | dva | deux | dos | due |

| three | drei | tre | trzy | tri | tři | trois | tres | tre |

| four | vier | fyra | cztery | štyri | čtyři | quatre | cuatro | quattro |

| five | fünf | fem | pięć | päť | pět | cinq | cinco | cinque |

| six | sechs | sex | sześć | šesť | šest | six | seis | sei |

| seven | sieben | sju | siedem | sedem | sedm | sept | siete | sette |

| eight | acht | åtta | osiem | osem | osm | huit | ocho | otto |

| nine | neun | nio | dziewięć | deväť | devět | neuf | nueve | nove |

| ten | zehn | tio | dziesięć | desať | deset | dix | diez | dieci |

Family relationships are also fundamental concepts and are, unsurprisingly, similar across languages:

| Germanic languages | Slavic languages | Romance languages | ||||||

| English | German | Swedish | Polish | Czech | Slovak | French | Spanish | Italian |

| mother | Mutter | mor | matka | matka | matka | mère | madre | madre |

| father | Vater | far | ojciec | otec | otec | père | padre | padre |

| sister | Schwester | syster | siostra | sestra | sestra | sœur | hermana | sorella |

| brother | Bruder | bror | brat | bratr | brat | frère | hermano | fratello |

All these words derive ultimately from a language ancestral to almost

all European languages known as Proto-Indo European and that language

was also ancestral to Sanskrit, other South Asian languages and Persian

among many others.

The presumed Proto-Indo European words were:

Father: pəter (which is related to the Sanskrit pitar,

the Latin [and Greek] pater and the Old Persian pita)

Mother: mater (which is the root of many

cognate words from South India to Ireland)

Sister: swesor (recognisable almost unchanged in

Indo-European languages from the Sanskrit svasar to the Russian

sestra)

Brother: bhrater (another almost unchanged word recognisable in

the Sanskrit bhrátár, Old Persian brata, Greek

phratér, Latin frater, Old Irish brathir, Welsh

brawd etc.)

Problems with true friends

- Because the words look so similar, learners are tempted to pronounce them as they would in their first language(s). This results in lots of incorrect stress and phoneme production.

- Because word formation, and especially the use of suffixes, works differently across languages, learners may mistake word class, confusing nouns with verbs and adjectives and so on.

- A word which is basically a true friend may have slightly

different connotations or uses in particular registers.

For example, Angst in German means worry or anxiety (both as nouns only) but does not carry the special psychological sense which the word has in English. Similarly, the verb demander in French simply means to ask and carries none of the sense of insistence and authority that the verb demand carries in English. - Many true friends in English for speakers of Latin-derived

languages are stylistically inappropriate and too formal. For

example, while

I administered an aspirin to him

may communicate the sense, it would be more usual to use

I gave him an aspirin.

|

False friends deceive |

Cognates may have the same origin but often do not have the same meaning because languages develop in different ways. For example, the word dish in English and the word Tisch [table] in German both derive from the Latin for a disc but they no longer mean anything like the same thing. Fortunately, Tisch and dish look sufficiently different for learners of either language not to get too confused. Some pairs of words are not so obliging.

In other cases, a word may be a loan word rather than a cognate but has developed a different sense in the language into which it was borrowed. As we saw above, for example, the word Angst (German for worry or fear) has been borrowed in English but only in a special psychological sense. The word smoking has been taken from English into French (and other languages) where it ends up meaning a kind of dinner jacket.

At other times, a word may derive from the same sources in a

range of European languages but have either shifted in meaning in

English or, as is often the case, remained true to the original

meaning in English but drifted away from the original in other

languages.

Here are some other examples of slowly shifting meanings of cognate

words:

- sensible

This derives in both English and in Romance languages in which the cognates mean something like sensitive. However, in English, that meaning is now considered old fashioned as in, e.g.:

I am sensible of his concerns (i.e., aware of)

and the meaning is usually considered to be logical or reasonable as in e.g.:

That's a sensible idea

The words sensitive and sensible are well known false friends across a range of European languages and English. - sympathetic

In English, the word retains its original meaning of having a shared feeling (derived from the Greek) as in e.g.:

You could be a bit more sympathetic to his problems

However, in related languages, the meaning has often drifted and the term can be applied to a place or environment which is pleasing or comfortable.

English has borrowed simpatico from Italian to represent the sense of comfortable but that, too, is beginning to drift way from its Italian meaning. - actual

This word derives from the Latin actualis, meaning active or pertaining to action.

In English, the word now means something akin to real as in, e.g.:

This is the actual desk where Dickens wrote some of his books

However, in other European languages the cognate term (French actuel(le), German aktuell, Italian attuale, for example), means something like current or up to date. - warehouse

This is a compound word, derived from ware (goods for sale) and house (accommodation) and in English, it refers to a large storehouse. Both ware and house are derived in the same way in Dutch (waar + huis) and German (Ware + Haus), but in Dutch, the meaning has changed to a department store or simply a large shop. In German and English, the meanings of the cognates are parallel. - eventual

Since the middle of the 19th century, this word in English means final or ultimate as in, e.g.:

The eventual winner was quite unexpected

However, there is an earlier use in English in the 17th century of the word to imply contingent, meaning something like under certain circumstances, and that is the meaning that is retained in other languages such as German, Swedish and Dutch.

In French, the term éventuel may mean prospective.

Whatever you may read on the web out here, these are false friends and are specifically and definitely not false cognates (see above for a definition of those). Some false cognates may, in fact, be false friends but all false friends should not be called false cognates.

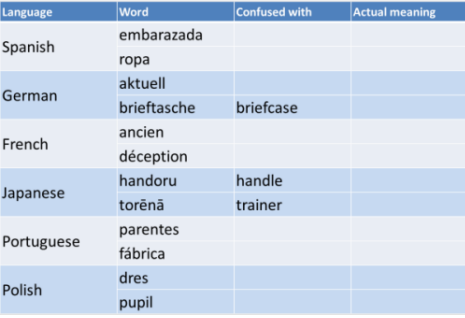

In the following, some words are cognates and others are loan words. It doesn't matter for the purposes of helping learners recognise false friends and avoid embarrassing mistakes.

Take the following for example. Can you fill in the gaps? Click on the table when you have:

The list for all these languages can be considerably extended. Moreover, related languages will often share characteristics so what is a false friend for an Italian speaker will probably (not certainly) be one for a French, Spanish, Portuguese or Romanian speaker, too.

|

Grammatical similarities and differences |

Although the term cognate applies purely to lexis, there are

similarities and deceptive differences between the grammar of related

languages.

English is a West Germanic language (allegedly – there are those who

prefer to call it a North Germanic language) and its grammar reflects its origin.

Although the language has been hugely enriched by borrowings from

French, Latin, Greek and a range of other languages, its grammar remains

recognisably Germanic.

There are obvious advantages for people whose first languages are

Germanic when it comes to learning English but there are also some

pitfalls which may be considered a form of grammatical or structural

false friends. Here are some common examples:

- comparative and superlative forms

- Cognates of the word longer in English and other

European languages are instantly recognisable. The word

translates, for example, as:

länger in German

lengur in Icelandic

längre in Swedish

lenger in Norwegian

langer in Dutch and Afrikaans - However, English cannot inflect the comparative form in the same

way for longer words so, more interesting translates as:

interessanter in German

áhugaverðari in Icelandic

interessanter in Dutch

and speakers of those languages may be tempted to produce *interestinger in English.

Speakers of Swedish and Norwegian will not because similar rules apply and the phrase is:

mer intressant in Swedish

and

mer interessant in Norwegian.

In the latter two cases, we have a form of interlanguage facilitation rather than interference. - modal auxiliary verbs

- Across Germanic languages, these verbs are also recognisably

derived from the same sources so must and can

translate as:

müssen and kann in German

måste and kan in Swedish

må and kan in Norwegian

moet and kan in Dutch

However, the meanings are subtly different and the associated grammar can also be misleading. For example:

I must not

means

I am forbidden to

in English, but means

I don't have to

in many related languages. - tense forms

- Superficially these look very similar so, for example, I

have seen translates as:

ich habe gesehen in German

ég hef séð in Icelandic

jag har sett in Swedish

jeg har sett in Norwegian

ik heb gezien in Dutch

However, the sense of the present perfect in English is rarely parallelled in other languages so most of these translations apply equally well to I saw. In other words the relative or relational tense in English may be an absolute tense in other languages.

The same considerations apply to a range of other related languages in which a tense form may look similar but actually carries a distinctive meaning not parallelled in another language. - conjunctions

- Conjunctions are usually ancient words which share roots in a

range of related languages but have, over time, become distinctly

different in meaning. For example: the word because

translates as:

weil in German (cognate with the English while)

därför att in Swedish (cognate with the English therefore)

fordi in Norwegian (cognate with the English for that)

omdat in Dutch (cognate with the English for that)

Similarly, the conjunction when in English translates as:

wann in German (cognate with when)

när in Swedish (cognate with near)

når in Norwegian (cognate with near)

wanneer in Dutch (cognate with when near)

and if translates confusingly as:

wenn in German (cognate with when in English)

om in Swedish (cognate with when)

hvis in Norwegian (cognate with if)

als in Dutch (cognate with as) - prepositions

- Apart from the difficulties of assigning the correct preposition

to prepositional verbs such as depend on, stare at and so

on, prepositions which are superficially derived from the same root

are used very differently across a range of otherwise closely

related languages so, for example, wait for in English

translates as wait on in German (warten auf),

Dutch (wachten op), Swedish (vänta på) and many

other related languages.

The expression arrive at sometimes translates as arrive to, arrive at or arrive by, in related languages.

This is an obvious source of considerably error.

Other prepositions are more friendly so over as in over the wall translates as:

über die Mauer in German

yfir vegginn in Icelandic

över väggen in Swedish

over veggen in Norwegian

over de muur in Dutch - articles

- Although articles are common to most Germanic languages, the way in which they are used is not always similar. Many languages which are related to English in this regard can use an article as a pronoun which is not allowed in English and there are subtleties of use, such as when the definite article may be used with a proper noun, which vary between languages and catch out the unwary learner.

| Related guides | |

| the roots of English | for more about the origins and development of English and its vocabulary which helps to explain why false friends occur at all |

| types of languages | for a more technical guide to how languages vary and how they are related |

| interference and facilitation | for a guide in the in-service area which considers how the nature of people's first language(s) can help or hinder the learning of English |

| false friends exercises | some exercises for learners deliberately targeting false friends in a number of languages |