Unit 10: texts

Throughout this course, the longest texts we have dealt with have

been full sentences and quite often we have been concerned with much

shorter stretches of language.

The course would not be complete, however, without some

consideration of texts in English.

What we are looking at in this unit is any text above the level of a single sentence either written or spoken so, for example all the following constitute texts worthy of some analysis:

- War and Peace

- A four-part conversation in a shop between a customer and a salesperson

- A five-page transcription of a classroom interaction

- An essay written by a learner of English

- A PhD thesis

- This page

- This whole website

- A newspaper

- A newspaper article

- An announcement at a station

Here's the menu and, as usual, clicking on the yellow arrow at the end of any section will return you to it.

| Section | Looking at: |

| A | Types of text The most important genres or text types. |

| B | Themes and rhemes How texts hang together. |

| C | Understanding

texts (a footnote) Two ways to approach texts. |

Section A: types of text

|

Genres |

The first thing to be clear about is that here we are using the

word genre in a technical sense applicable to language

studies.

We are not, for example, discussing genres in literature such as

sci-fi, detective stories, historical novels and so on and nor are

we considering musical genres such as rock, jazz, classical, ballet

etc.

In language teaching, genre can be defined as a class of texts

having the same purposes in the culture and therefore sharing the

same structural, grammatical and lexical characteristics.

For example, if you have before you the instructions for using a

microwave and for building a swimming pool they will clearly be very

different. However, they will share elements

concerning layout of controls and parts, operations, safety features

and much more and you will know almost instantly that you are

looking at texts in the same genre.

Equally, if you go into a shop intent on buying a new computer, then

the transaction will follow similar lines, using the same ordering

of events that buying a sandwich at the station buffet will show.

|

Seven types of text |

Whether these are written or spoken, the following genres share

some characteristics because they are intended to achieve the same

ends.

This is not a complete list because definitions of genres can be

narrow or broad but it covers most eventualities.

- RECOUNT

- the setting out of a sequence of events to say what happened and

describe their significance. A spoken recount might begin with:

A funny thing happened to me on the way to the office this morning.

Other examples might include:

an anecdote, an excuse for being late, a joke, a complaint about a journey - NARRATIVE

- to retell a set of events with a problematic or unexpected

outcome to entertain and/or instruct. A narrative might

begin with:

Once upon a time ...

Other examples might include:

a novel, a short story, fables, parables - PROCEDURE

- to explain how to do something. An example might be

something that came with a piece of self-assembly furniture and

might begin:

Locate leg A and bolt Z.

Other examples might include:

recipes, manuals, maintenance instructions - INFORMATION REPORT

- to provide information about something (that's what this

text is doing). Such texts usually begin with headings

stating the topic.

Examples might include:

encyclopaedia entries giving information about things, text book sections, grammar books, reports of experiments, news reports - EXPLANATION

- to say why and how something happens. An explanation

often involves explaining cause and effect so such a text might

begin:

Above 2000 meters, the air becomes noticeably thinner so water boils at a lower temperature. This causes ...

Other examples might include:

web pages like this, encyclopaedia entries explaining processes - EXPOSITION

- to argue a case. This is a one-sided view and a

typical exposition text might begin:

We the undersigned write to protest that ...

Other examples might include:

political pamphlets, leader columns in papers, letters to the editor - DISCUSSION

- to present both sides of a case before (possibly) coming to a decision.

A typical discussion text might begin:

There is a range of views about the usefulness of the passive voice form in English. Some believe ...

Other examples might include:

academic texts, student essays, histories

And here are the ways that these texts are usually staged with a very simple and very short example text to give you the idea:

| Genre | Staging | Very simple example |

| RECOUNT | Orientation: who/what is the story

about? Record of events: in chronological order Reorientation: what happened in the end? Coda: how did I feel/think/react? |

I was in London for the first time. I visited lots of museums and galleries. I went home in the evening. I enjoyed it all but was tired. |

| NARRATIVE | Orientation: who/what/where? Complication: the crisis/problem and an evaluation Resolution: how was the problem resolved? Coda: how did I feel/think/react? |

My friend and I were on the train. I suddenly realised I had lost my ticket. I had to pay for a new ticket. It was not a good day because I lost a lot of money. |

| PROCEDURE | Goal: what do you want to do? Materials: what do you need? Steps in sequence |

To plant the tree: You will need a spade and some fertiliser. Dig a large hole, put in the fertiliser and then the tree. Fill in the hole and water it well. |

| INFORMATION REPORT | Identification: what's it about? Description: sections bundled in topic areas |

Owls live near my house. They only come out at night and then they hunt for mice and other animals. They have chicks in the spring time. |

| EXPLANATION | Identification: what am I explaining? Explanation: the phases in the process |

Olive trees are often attacked by a kind of fly which lays its eggs in the unripe fruit. The fruit does not ripen properly because of this and the oil yield is reduced. |

| EXPOSITION | Statement of position Preview of arguments Arguments: statement + evidence in each case Restatement of position |

People should not study grammar. It's too difficult because there are lots of rules. It doesn't help you speak because you can't remember the rules. So don't bother with it. |

| DISCUSSION | Issue Arguments for Arguments against (All the arguments for can follow each other before arguments against [FFF followed by AAA] or they can be interwoven [FAFAFA].) Optionally, this genre may have a conclusion stating the writer's view. |

Grammar may be useful. Some

people like learning rules and working things out because it

interests them. Other people don't enjoy it because it's boring. Grammar helps you write well because you have time to think. Grammar doesn't help you speak because there's too much time pressure. Grammar maybe useful for some people. |

|

Why do people need to know this? |

If you are aware of the structure and content of the various text types, two things become immediately easier:

- You can read and listen more quickly with better understanding because you know where the information is likely to be placed and you know that the stages will follow a predictable pattern.

- You can produce written and spoken texts which will not disorientate your listener or reader because you will be following a pattern with which they are familiar. Deviating from the pattern will confuse and irritate the reader / listener who may start to think you can't speak or write properly.

|

Learn more

genres |

|

Take a test |

To see if you have this, try a test.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section B: theme and rheme

|

It follows naturally |

This section looks, quite briefly, at how parts of texts (long or

short) hang together.

Unit 9 considered cohesion (i.e., grammatical and

lexical linking devices) but here we are focused on

coherence.

To see the difference, consider these two dialogues:

- Where's Peter?

- He's in the garden

- Where's Peter?

- The grass needed cutting

Both these dialogues are coherent but they are very different.

In the first, B's answer includes the pronoun he which

clearly refers to Peter and it also contains in the

garden which is reference to a place and answers the question

where.

In the second, there is no such linking because the answer

makes no reference either to Peter or the place and appears

unconnected.

However, we can use our knowledge of the world to assume two things:

- the grass is found in the garden

- it is Peter's usual task (or even his job) to cut the grass.

and in this way, we can understand what's going on.

Texts work in similar ways and may lack cohesion while still

remaining coherent (and they may do both, of course).

To see what's meant now, compare these two pairs of sentences:

- Mary went to London with her mother and brother. Of course, the British Museum was on the list of things to see because the boy had spoken about wanting to see the Darwin exhibition.

- Mary took her mother and brother to London. The city has always delighted her and she wanted to show people around.

In neither of these little recount texts is there any obvious grammatical linking between the sentences but if we change them around, we get a rather odd result. Like this:

- Mary went to London with her mother and brother. The city has always delighted her and she wanted to show people around.

- Mary took her mother and brother to London. Of course, the British Museum was on the list of things to see because the boy had spoken about wanting to see the Darwin exhibition.

The reason that texts 1. and 2. flow more naturally is to do with themes and rhemes. Here is how it works:

- In both the first sentences the theme is Mary (because that is who the sentences are about)

- However, the second parts of the first sentences have

different rhemes:

- in text 1., the rheme is her mother and her brother so it is logical that the next sentence concerns one of them. In this case, it takes her brother's wishes as its theme. We might expect the text to go on to consider what her mother wanted to do.

- in text 2., however, the rheme is London because that comes last in the first sentence. It is therefore logical that the next sentence should take the city as its theme.

There is, rather predictably, a lot more that can be said about

themes and rhemes but if you have followed that, you are on your way

to being able to analyse texts rather than sentences in isolation.

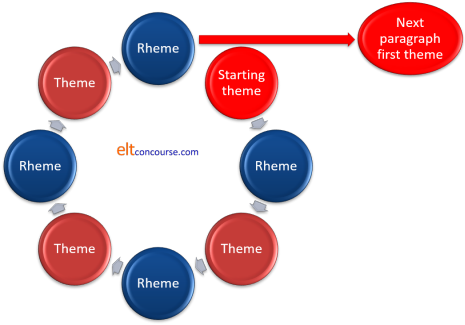

A written longer text will often hold together in this way and many

spoken ones will also have a similar structure. It looks like

this:

It's not that simple in reality very often because rheme 1 may wait

for a while before it becomes a theme in its own right and some

rhemes may never get that status.

|

Learn moreTry this link to learn more: |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try a test to see if you can recognise theme-rheme structures.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section C: understanding texts

|

I get it! |

This section is a footnote and you may be pleased to know that there's no accompanying test.

The usual analysis of how people understand texts, whether they are spoken or written, identifies two strategies. However, there are behaviours which fall uncertainly into one category or another and some which clearly have to be employed in tandem with others to be effective. The two approaches are:

- Top-down processing

This takes an overall view of a text (spoken or written) and attempts to understand it by using:- knowledge of the world (sometimes called encyclopedic

knowledge)

which tells us, for example, that when we hear an announcement in a railway station it will probably be information about times and locations or safety issues and that when we sit down to watch an evening news programme on TV, we are already primed to understand the types of stories and even the topics which will follow.

Equally, when we pick up a novel or a short story, we usually know what it is about and what kind of story it is. We very rarely read or listen to anything without knowing a good deal about the text beforehand and that aids our comprehension because we are not reading or listening for just anything that comes along, we are using the skills for something identifiable. - knowledge of social relationships

which alerts us to the intentions of writers and speakers. If we know why something is being written or said we are well on the way to understanding what is being written or said.

For example, if we pick up the sports page of a newspaper, we are alert to the fact that it will contain reports of games and matches and may also contain interviews with sports people and schedules of events. We do not come cold to the text.

When we are spoken to by anyone at all, we usually know what the person's role is (friend, authority figure, informant, salesperson etc.) so we are primed to understand the sorts of things they are likely to say. - knowledge of the structure of the text

which helps us to locate the information we need. This functions in two ways, too:- generic structure

helps us to know where in a text to look or listen so we know, for example, when reading a procedural text that we are likely to find the materials we need at the beginning and a step-by-step explanation of what to do following that. If someone is giving us the instructions for a procedure orally, we know, too, that the information will (or should) come in comprehensible, logically ordered packets. - theme-rheme structure

helps us to locate the topic because the first line of any text (written or spoken) will usually contain an identification of the topic and the rheme of that sentence will often form the theme of a subsequent sentence or section.

In fact, we can listen to or read only the first sentences in texts and ignore the rest and still manage to get the gist and sometimes much more than that.

- generic structure

- knowledge of the world (sometimes called encyclopedic

knowledge)

- Bottom-up processing

This approach focuses analytically on the structures and lexis of the language and our understanding is helped by our knowledge of:- the phonemes and other features of the spoken language

which helps us to break up the stream of speech and identify individual words as well as the attitudes of the speaker and the functions (questions, enquiries, warnings, agreement etc.) of what is being said. - the morphemes and lexemes

which helps us to decipher unknown words by looking at their internal structure and also to recognise words we know, of course. We know, therefore, or can infer, that the word untidy is the opposite of tidy, that opened is the past tense of open and so on. - the grammar and structure

which helps us to identify relationships between words and word classes so if we hear or read, for example:

He gave it an almighty thump with a hammer

we can infer that almighty is an adjective, that thump is a noun (because of the ending on almighty and the presence of the article an) and, if we know the word hammer, we know what sort of noun it must be.

Equally, if an unknown word appears preceded by this, that, these or those we are alert to the fact it's probably a noun but if it appears between an article and a noun, then it's an adjective. We know, too, that nouns and noun phrases form subjects and objects so we can look for the head of phrases in something like:

The fractious horse with the white facial flash was neighing irritably in its stable

and be able to reduce that to

The horse neighed in its stable

which gives us all the information we need for now without troubling about the other elements. We also know, of course, that neigh is something horses do and our knowledge of the world allows us to guess what it might be. If we don't know the word stable, it's not too hard to figure out what it is from the fact that horses are found in them.

Lastly, if we see:

The alligator devoured the fish

and we know the words alligator (because it's the same in many languages) and fish (because it's very common) we can be pretty certain of the meaning of devoured and know, incidentally, that it's a regular verb.

- the phonemes and other features of the spoken language

We must emphasise again that these approaches are not in an either-or relationship. Good listeners and readers use them simultaneously to make sense of what they hear and read.

|

Learn more

inferencing |