Unit 3: content (meaning-carrying) lexemes

This Unit is concerned with what most people think of a real

words because they carry meanings we can define or check out in a

dictionary.

This is quite a long unit because it deals with some very important

ideas and terminology. Without a good understanding of the

major word classes analysed here, you will find teaching English an

impossible task.

There are 6 sections to this unit and here's the menu.

Clicking on the yellow arrow at the end of each section will return you

to this menu.

| Section | Looking at: |

| A | What is a content

lexeme? The difference between content and function words. |

| B | Nouns Major classes of nouns. |

| C | Verbs Major classes of verbs. |

| D | Adjectives Major classes of adjectives. |

| E | Adverbs Major classes of adverbs. |

| F | Types of meaning What does mean mean? |

| G | Types of

relationships How words work together |

Section A: identifying content words

|

A task |

In this list there are 5 content words which carry meaning even

when they stand alone and 5 function

words which do not.

Can you identify them? Click on

![]() to show the answer

to show the answer

| 1 | carrying | 6 | probableish |

| 2 | about | 7 | out |

| 3 | much | 8 | hers |

| 4 | chance | 9 | this |

| 5 | happiness | 10 | cosily |

| 1 | carrying | This is easy to define and clearly has a meaning. It's a lexical word or content lexeme. |

| 2 | about | This is a function word and signals

different meanings in, e.g.: We spoke about the problem We walked about a mile |

| 3 | much | This is a function word (a type of determiner) and signals a quantity but standing alone, it's meaningless. |

| 4 | chance | This is easy to define and clearly has a meaning. It's a lexical word or content lexeme. |

| 5 | happiness | This is easy to define and clearly has a meaning. It's a lexical word or content lexeme. |

| 6 | probableish | You won't find this in a dictionary but most people will still be able to define it (roughly) so it's a lexical word or content lexeme. We often tone down the sense of an adjective by adding -ish to it. |

| 7 | out | This is a function word and can be

a preposition or an adverb as in, e.g., respectively: They walked out the door We walked out |

| 8 | hers | This is a function word and

signals a possession or origin but standing alone, it's

meaningless. In a context, we may know what it means,

as in, e.g.: Whose is that car? Hers |

| 9 | this | We know this is a word referring to

something close to the speaker but we can only understand it

in a context such as: Do you want that hammer or this? In the first case, it's a determiner and in the second it's a pronoun. |

| 10 | cosily | This is not very easy to define but clearly has a meaning and a dictionary will give it to you after the meaning of the word cosy. It's a lexical word or content lexeme. |

In the list above, we have examples of all the four major word

classes which are meaning carrying or content words. We can

also call them content lexemes.

They are:

1. a verb (carrying)

4. a noun or a verb (chance)

5. another noun (happiness)

6. an adjective (probableish)

10. an adverb (cosily)

and in what follows, we will discover more about these essential

word classes.

|

Reminder |

We saw in Unit 2 that words like these are open-class items. That means, of course, that we can never come up with a completely comprehensive list of any of these classes of words because as soon as we think we have a list someone will say goodlookingish or thingummydoobrie and the list is instantly incomplete.

|

A note about words and phrases |

In what follows we will usually be considering single words

(because it's easier and more straightforward) so we have, for

example:

house as a noun

go as a verb

red as an adjective

soon as an adverb

but we also need to remember that

garden tools is a noun phrase

wind surf is a verb phrase

red coloured is an adjective phrase

from time to time is an adverb phrase

so we should really be talking about noun, verb, adjective and

adverb phrases,

not words because the slot test we saw in Unit 2 for word class will

work whether the item is a single word or a phrase acting as

a single word.

We won't complicate matters everywhere in this unit but you need to

bear that in mind.

(Unit 8 of this course considers phrases in a bit more detail.)

Section B: Nouns

|

Sorts of nouns |

On this site, we use this classification but you may see others, especially in older books.

- Common nouns

are the most frequent and apply to things, feelings and people. For example:

church, house, hill, village, tree, sugar, use, table, computer

and many thousands more.

All the items in the picture above can be represented by common nouns in English.

They are of two basic sorts:- count nouns

take a plural and can come with a singular or plural verb form. For example:

There are two cows over there

She has a new car

That's the first problem we need to solve

We have four good neighbours

etc. - mass nouns

refer to things we do not count and come only in the singular (except in some special uses). For example:

The furniture is worn out

Would you like some coffee?

I enjoy running

She has no time

We are taking food with us

etc.

For more about the difference between count and mass nouns, read on.

- count nouns

- Proper nouns

are usually spelled with a capital letter (in English) and refer to people, jobs, times and places. For example:

I spoke to Fred

He is the Chief Executive Officer

Come on Monday

I went to Berlin

There are some special rules for these, explained below. - Collective nouns

refer to groups of people and things and can be either singular or plural. For example:

They have joined a new class

She keeps a flock of sheep

The police are coming soon

The government is about to fall

She served in three brigades

For more, see below.

|

Proper nouns |

| Albert Einstein |

Proper nouns are the names for people and places. They usually begin with a Capital letter. There is a range of types and a number of difficulties for learners and teachers:

- People

- Mary, Tiger Woods, Mr Smith, Uncle

Fred

etc.

English does not use an article with proper nouns for people unless we are distinguishing two people with the same name as in, e.g.:

No, I don't mean the John who works in IT, I mean the John from Finance.

Many languages routinely use an article with people's names so elementary learners in particular may say something like.:

*I'll talk to the Mr Smith

English can use an article with names if there is some restriction:

the young King Edward, the old Mr Smith etc.

English, exceptionally, uses the articles with some titles:

the Duke of Westminster

the Reverend Smith

but not

*the Bishop Smith

*the Lord Michael

- Mary, Tiger Woods, Mr Smith, Uncle

Fred

etc.

- Jobs and Positions

- The President, The Pope,

The Managing Director, The Queen etc.

We usually put the definite article, the, before these nouns because there is only one of them that is the reference (although, of course, there are a number of presidents, queens, kings, prime ministers and so on, but both speaker and listener know which one is the topic).

- The President, The Pope,

The Managing Director, The Queen etc.

- Times

- Monday, February, the summer, Christmas, Easter

- Capitalisation:

Days, months and festivals are capitalised but seasons are generally not capitalised in English (other languages do things differently). - Article use:

When the noun is used with a unique meaning for days, months and festivals, the article is omitted:

On Monday, in February 1934, at Christmas etc.

When the nouns are restricted in some way, the article is used, especially with the adjectives previous and following:

the previous March, the following Christmas, the May of 1986, the Monday afterwards

Seasons are a little tricky. They usually function as common countable nouns, see below, and take the article normally:

I enjoy the summers here

The winter is always harsh in Scotland

They can, however, function like other times and the article is then omitted:

She came in spring and stayed till autumn - Plurals:

Days of the week and seasons regularly take plurals:

I spent many summers in Spain

I get bored on Sundays

- Places and buildings etc.

- Britain, Germany,

Margate, London, Lake Victoria, Jamaica, The Thames, The Suez

Canal, Baker Street, St Paul's Cathedral, The Tate Gallery etc.

The use of the article is idiomatic in English (not so in many languages) so this is a cause of a good deal of error. There are some rules of thumb, however:- rivers, mountain ranges and

canals

We usually put the before these: The Thames, The Nile, The Himalayas, The Alps, The Suez Canal, The Panama Canal - lakes, countries, islands, streets and

cities

We do not usually put the before these:

Lake Tanganyika, France, Crete, Rome

But we do put the in front of the name of the country if it contains a classifying adjective like united or Arab:

The United States of America, The United Kingdom, The Federal Republic of Germany, The United Arab Emirates

One or two countries have, in the past, been used with an article but the practice is dying out: The Sudan, The Argentine, The Gambia, for example.

There are some exceptions including:

The Hague, the Bronx, the City (of London), the Strand, The Mall etc. - buildings and mountains

This is a very idiomatic area and not easy to learn or teach because there are rules of use rather than rules of grammar. Again, a classifying adjective denoting the name of the building or mountain will usually compel the use of the article.

The Guggenheim Museum, The British Museum, Scotland Yard, Mont Blanc, The Eiger - continents

Do not usually take the article and are always capitalised so:

Asia, Europe, (South) America, Antarctica etc.

but

the Antarctic, the Arctic - directions

Usually take an article as in, e.g.:

The east

The north west

etc.

Most writers do not capitalise these but some do.

- rivers, mountain ranges and

canals

- Britain, Germany,

Margate, London, Lake Victoria, Jamaica, The Thames, The Suez

Canal, Baker Street, St Paul's Cathedral, The Tate Gallery etc.

|

Collective nouns |

In all languages, some nouns are used for groups of things or

people. In English, these can be both singular and plural but

in most languages they are only singular. For

example, in English, we can say:

The army is very large (thinking about it as a single thing)

and

The army are helping (thinking about

the army as a lot of

individual people)

We can also have:

The football team

are playing

on Sunday

and

The football team

is playing on Sunday

In the first one, we are thinking about all the players

separately; in the second one we are thinking of

it as a single

unit, the team.

Other collective nouns are, e.g., navy, crew, flock, herd, staff,

family, committee,

government, class, staff etc.

In American English these

words are normally used with a singular verb as is the case in most

languages.

|

Plural nouns |

One class of nouns appears only in the plural.

- Pairs:

Some tools and items of clothing appear in the plural because the phrase a pair of is usually omitted in English, e.g.:

scissors, pliers, tongs, shears, secateurs etc.

shorts, trousers, tights, flannels, socks, dungarees etc. - Pluralia tantum (the singular of which is

plurale tantum) are nouns which only appear in the

plural or are used in the plural with a particular sense.

There are plenty of these and when they occur in your teaching,

you need to point out their special use. Some examples

will suffice (a '-' in the second column means that there is no

obvious singular noun equivalent):

plural singular difference funds fund money vs. a collection of money brains brain intelligence vs. thinking organ customs custom checking of luggage vs. usual practice guts gut courage vs. digestive organ clothes cloth attire vs. piece of material arrears - amends - annals - auspices - contents - fireworks firework display vs. individual device greens - heads head side of a coin vs. part of the body looks look appearance vs. the act of looking minutes minute record of proceedings vs. time period pains pain efforts vs. unpleasant feeling remains - surroundings - tropics tropic warm areas of the world vs. line of latitude wits wit intelligence vs. amusing person

This list can be greatly extended

- Invariable unmarked plurals

A few words in English are plural but take no inflexion to show it. Examples are:

cattle, clergy, people, police, vermin

|

Mass nouns and Count nouns |

|

| milk | pencils | |

The distinction between these two types of nouns either does not exist at all in some languages or is very differently handled. The problems for learners in this area are extensive.

- Most nouns in English are count nouns. Count nouns have a

singular (for one) and plural (for more than one). This means

we can say, for example:

I have three pencils

I want that pencil

The pencil is here

Those pencils are no good

Please give me a pencil

I have several pencils on the desk

Count nouns cannot usually appear in the singular without an article (a(n) or the) so we do not find:

*Pencil is needed

*Person is here

etc. - Many nouns in English are mass nouns. These nouns do not

have a plural. We can say, for example:

I want that milk

I have some milk

The milk is here

This milk is bad

Please give me some milk

I have some milk in the glass

Mass nouns always use a singular verb and never take a plural.

Most mass nouns are:

Materials: metals, liquids, gases, cloth

etc. For example: It's made of iron She needs water There's no air in here The chair is covered with blue cloth |

Ideas and Feelings For example: She has no understanding You have my sympathy Love is important for children His anger was clear |

Small objects For example: They grow rice here The sand gets in my shoes The dust is everywhere Use milk powder in the pudding |

States For example: I need more sleep Childhood is a good time You can't buy happiness |

Weather For example: There's a lot of snow this winter We have a lot of rain in the spring The sunshine is nice |

There are hundreds of mass nouns in English but here is a list of very common ones:

|

advice air anger art bread cash cheese childhood clothing coffee damage danger education energy equipment fire food freedom friendship |

fun furniture gold hair happiness health heat help honesty housework humour imagination information intelligence kindness knowledge labour laughter love |

luck management metal milk money music news paper pronunciation punctuation quality quantity rain rice rubbish safety sand shopping sleep |

smoke snow soup sport strength sugar sunshine tea time traffic transportation travel understanding warmth water weather weight wood work |

That list is available as a PDF document from this link.

It is possible, of course, to make mass nouns countable by the

addition of what is called a partitive or a quantifier as in, e.g.:

three hours' sleep

a piece of iron

a bar of chocolate

two means of transportation

pints of milk

drifts of snow

etc.

As you see, however, the choice of quantifier or partitive is

not an easy one to make.

|

Learn moreIf you want to discover more now about nouns, go to: |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your

knowledge of nouns.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section C: Verbs

|

Types of verbs |

This unit is to do with content lexemes or lexical words, not

function words but, unfortunately, verbs happen to occur in both

categories.

Here we will focus on what are usually called Main Verbs but you

should know now that there are two other basic sorts of verbs.

Unit 6 looks at Primary auxiliary verbs (be, have, do, get)

and Unit 9 looks at Modal auxiliary verbs (may, might, can,

should etc.).

For our purposes here, there are two forms of verbs that behave rather differently:

- Copular or linking verbs

These verbs act to link a noun to an attribute or a noun to another noun. The verbs in red in these examples are copular verbs:

John is happy

Mary is the manager

I became very irritated

She grew old

That appears perfect

She seems depressed - Main or lexical verbs proper

These verbs refer to actions, states and events and the examples in red are all main verbs in the true sense of the expression:

The water flooded in

Peter told me a joke

She arrived late

I put it in the corner

We drove slowly

We'll take each category in turn starting with the first because they are the simplest.

|

Copular verbs |

| it was attached |

Copular verbs have some quite peculiar characteristics in terms

of what they may link together and if you want to know more, there

is a guide, linked below, which analyses them more thoroughly than is

possible here.

The only verb which can be described as the pure copular verb is

be and it is the most flexible and frequently used in this

function. It is sometimes described as the colourless copula

because it carries no intrinsic meaning.

The verbs be, become, remain, stay and end up are

all quite versatile and can

be used:

- to link together a noun and an adjective (called the

attribute) as in, e.g.:

She was angry

He became unhappy

They remained dissatisfied

I stayed happy

She ended up frozen

etc. - to link a noun to another noun as in, e.g.:

The tree was an ash

Mary became a gardener

They remained students here

He stayed a soldier

She ended up a prisoner

The important issue here is that the two noun phrases refer to the same thing or person so the tree and ash are the same, as are Mary and a gardener and so on. The term for this is that they are co-referential.

Other common copular verbs cannot link two nouns and only work to

link a noun and an adjective. The common ones are seem,

appear, sound, smell, taste and feel.

This means we do not allow:

*She seemed a doctor

*She appeared a doctor

*It sounded a pop song

*It smelt fresh air

*It tasted apples

*It felt silk

but we allow:

She seemed content

She appeared angry

They sounded awful

It smelt fresh

It tasted delicious

It felt smooth

Here's a list of some common copular verbs with examples divided into those which describe a current state and those which signal a change of state (which is a good way to teach them):

| Current condition / state | Change of state / result |

|

appear unhappy be on the table feel sick look miserable remain unhappy seem excessive smell revolting sound awful stay calm taste good turn up dead |

become involved come undone end up rich get old go stale grow apprehensive fall ill turn aggressive |

|

Main verbs |

| the water flooded the house |

Main verbs are rather more complicated.

They come in three main sorts but some verbs can appear in more than

one category. The

first two categories are the really crucial ones.

- Intransitive verbs

Some verbs never take an object and can stand alone. We can say, for example,

They arrived at the airport

I responded

etc., and the meaning is clear.

However, for example, we cannot say

*She arrived the hotel

or

*It occurred the rain

because neither of these verbs can refer to a noun directly, i.e., they cannot take an object. We can, and frequently do, insert a preposition to get, e.g.,

She came to the hotel

or

It occurred towards the end of December

but the verb is still not taking an object in these cases.

Other examples of generally intransitive verbs include

agree, appear, belong, collapse, die, disappear, exist, fall, go, happen, inquire, laugh, live, look, remain, respond, rise, sit, sleep, stand, stay, vanish, wait.

Most of these can be followed by a prepositional phrase such as about the weather, at six o'clock, of hunger and so on but these are not objects of the verb. Technically, they are referred to as complements. - Transitive verbs

Verbs which are always transitive must have an object complement.

For example, we cannot have a sentence such as

*He brought

and we must insert an object and get:

He brought some flowers

because the verb bring must have an object to make any sense. We need to know both who or what did it and what or who it was done to.

Other examples of generally transitive verbs include: buy, cost, get, give, make, owe, pass, show, take, tell.

We can divide transitive verbs into two more categories:- Those transitive verbs which can take only one object.

These are called monotransitive verbs.

For example, we can say

She drank the coffee

but not

*She drank me the coffee.

Other examples of verbs which only take one object when they are transitive include eat, say, play, expect, remember, suspect. - Those transitive verbs which can take two objects. These

are verbs which are ditransitive. For

example, we can say

He bought the drinks

and that's a verb with a single object (the drinks) but we can also say

He bought us the drinks

and here we have two objects, the drinks (the direct object) and us (the indirect object).

Another example is

They sold me the car

which has a direct object (the car) and an indirect object (me).

We can also change the order and put the indirect object at the end but then we have to insert a preposition:

He bought the drinks for us

They sold the car to me

Other examples of verbs which can or even must be ditransitive include:

allow, appoint, ask, assure, award, bake, bet, bring, buy, call, cause, charge, cook, cost, cut, deal, do, draw, feed, find, get, give, hand, lend, make, offer, order, owe, pass, pay, promise, read, save, sell, send, show, teach, tell, throw, wish, write

In English, the indirect object comes before the direct object but that is not always the case in other languages.

There is more about subjects and objects in Unit 5 of this course.

- Those transitive verbs which can take only one object.

These are called monotransitive verbs.

For example, we can say

- Verbs which can be both transitive and intransitive

These verbs, and there are lots of them, can be both. They are called ambivalent verbs.

For example, we can say

She eats (intransitive)

and

She eats fish (transitive).

Other examples in this category include

drink, explain, help, decide, fly, smoke, swim, play, continue.

|

Regularity and irregularity |

Although there are lots of irregular verbs in English (around

200), learning them is not particularly difficult because the verbs

only have one or two changes at most.

In some languages, such as most European ones, life is much more

complicated and it may be necessary to learn more than ten forms for

each irregular verbs.

In English there are three forms of all main verbs:

- The base form of the verb:

All verbs, irregular or not have this form. Examples are:

arrive, go, be, enjoy, buy, sleep etc. - The past tense form:

These are either regular, adding -d after a base form ending in e or -ed after any other letter or they are irregular. Examples are:

arrived, went, was/were, enjoyed, bought, slept etc. - The past participle form:

These are again regular or irregular but if they are regular, they always have the same form as the past tense and even when they are irregular, most of the verbs retain the same form as the past tense. Examples are:

arrived, gone, been, enjoyed, bought, slept etc.

To make things even easier, there are only a few verbs which are truly irregular and most fall into groups with similar sounds which often rhyme. So, for example we encounter:

| Verbs which never change | put, cut, cost, rid etc. |

| Verbs adding -t | smell-smelt, learn-learnt, spill-spilt etc. |

| Verbs adding -t and changing /i:/ to /e/ | dream-dreamt, sweep-swept, weep-wept, mean-meant etc. |

| Verbs changing /ɪ/ to /ʌ/ | cling-clung, dig-dug, win-won etc. |

In many course books and other reference materials, you will

find an alphabetic list of irregular verbs and that is helpful

for reference but not so helpful for learners because it hides

the patterns.

Here is a list of the verbs organised into patterns which you

can get

here in PDF format:

|

Learn moreThere is more in this course about verbs. Units 5,

6, 7 and 9 are all concerned with verbs in some way because

they are so important. |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your knowledge of

verbs.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section D: Adjectives

|

Describing and classifying |

Adjectives are a major word class in all languages and the in-service guide to them on this site is one of the longest and most detailed.

An adjective is usually defined something like

a word grammatically attached to a noun to modify or describe it

Easy question:

Spot the adjectives in these examples:

- The tall trees bent in the fierce winds.

- He finally came along half an hour late for the first meeting.

- The green-jacketed, first-form students looked nervous.

- The audience was fascinated by the short lecture.

Click

![]() when you have answers.

when you have answers.

The adjectives are highlighted in black in the following:

- The tall trees bent in the fierce winds.

- He finally came along half an hour late for the first meeting.

- The green-jacketed, first-form students looked nervous.

- The audience was fascinated by the short lecture.

Some are easier to identify than others, aren't they? Here are some comments:

- Adjectives in English usually come

before the noun they modify. We can see this with

tall

trees, fierce

winds, first

meeting, green-jacketed,

first-form students

and

short

lecture.

This use of adjectives is called attributive.

Some adjectives are only used attributively. Examples are entire, outright, pure. We can have, e.g.:

He ate the entire packet

It was the pure truth

and

That was an outright lie

but we can't say:

*The packet was entire

*The truth was pure

or

*The lie was outright - In sentences 3. and 4., however,

we have the alternative adjective position: looked

nervous,

was fascinated.

Here the adjectives follow the noun they modify and are connected to it either by the verb be or by another verb which works in the same way. These are called, as we saw above in the section on verbs, copular verbs and you now know that one of their functions is to connect a noun with an adjective.

When the adjective is connected to the noun in this way, the use of the adjective is called predicative.

Some adjectives can only be used predicatively. Examples are asleep, awake, alive, alert etc. They start with a-. We can't say

*The asleep dog

and we need to say

The dog is / was / seems asleep

for example.

|

Tests for adjectives |

There are two simple tests for adjectives:

- We can make comparatives either by adding -er or -est or by putting more / most before them

- We can modify them with the adverb very

Try these tests with the adjectives we have encountered so far.

What do you notice?

Click

![]() when you have done that.

when you have done that.

-

We

can have: taller, fiercer,

more nervous,, more fascinated

and shorter

However, we can't have *firster, *more green-jacketed, *more first-form.

The reason is twofold:- Some adjectives simply cannot be made more or less: you are

either first or you aren't, something is either

impossible or it isn't. Such adjectives are called

ungradable.

Ungradable adjectives include those which represent an on-off, either-or distinction such as first, last, open, shut etc. Something or someone is either one or the other and there are no intermediate stages. - The second reason is that some adjectives tell us what

class

of thing we are dealing with. We can't have *very green-jacketed,

*very first form etc.

because these are classifiers.

Classifiers tell us what class or category of object or person we are considering and they also cannot be graded. The words include many nouns which are used as if they were adjectives. They include, for example, words such as French, electronic, school, plastic and so on which come immediately before the noun in most cases and also cannot be compared. A car can't be *a very sports car and we can't have a very plastic cup, for example.

An adjective which is not a classifier is sometimes called an epithet to distinguish it from a classifier.

- Some adjectives simply cannot be made more or less: you are

either first or you aren't, something is either

impossible or it isn't. Such adjectives are called

ungradable.

-

We can also have very

tall, very

fierce, very

nervous, very

short and so on. There's

some argument whether we can have very first in

this sense, because very means truly here, or very

fascinated because fascinated is usually considered

too strong a word to be modified by very. Compare it

with very amazing, very dreadful, very astounding etc.

These adjectives, sometimes called extreme adjectives, are not usually gradable with very (we prefer adverbs such as completely, totally, extremely etc. to modify them).

|

Comparing adjectives |

Adjectives can be made comparative or superlative.

Comparative structures are, for example:

Mary is taller

than John

Mary is more intelligent

than me

Superlative structures single

out one as the highest form of the adjective, e.g.:

She is the fittest person for

the job

That is the most ridiculous idea of them all

The

rules for how we make the forms apply to both.

English has two ways to compare adjectives:

- We can add -er or -est to the end of the adjective (dropping an 'e' or changing 'y' to 'i' where we need to). This is called inflexion.

- We can add more or most before the adjective. This is called a periphrastic form.

Try modifying the adjectives here and work out what the rules are. Click on the table when you have the answer. The following focuses on the comparative form but the superlatives follow the same rules.

There are some irregular ones (as in most languages) including, e.g., far-further/farther-furthest/farthest, good-better-best, bad-worse-worst etc. and there's a bit more to it than that but this is the simplest explanation.

|

Ordering adjectives |

Many books for students delight in giving complex and elaborate rules for why we say, for example:

- small, brown house

not

brown, small house - tall citrus trees

not

citrus tall trees - rude

English tourists

not

English rude tourists - ugly, fat, porcelain, Chinese vases

not

porcelain, Chinese, fat, ugly vases

But actually the general rule is quite

simple. Any ideas?

Click when

![]() you have

some.

you have

some.

- Classifiers like, English, Chinese and citrus go closest to the noun. Some classifiers are inseparable from the noun, e.g., schoolboys. They form a compound.

- Adjectives which are ungradable (i.e., cannot be more or less so) come next. The example here is porcelain. Something is either porcelain or it isn't. Often these relate to the material something is made of.

- Adjectives which are gradable but not very arguable come next. The examples here are fat and tall.

- Adjectives which are a matter of opinion come furthest from the noun. The example here is ugly (and probably, rude)).

The simple way to present this is on a cline, like this:

There is a bit more to this and for some detail, you should refer to the in-service guide to adjectives, linked below.

|

Learn moreIf you want to discover more now about adjectives, go to: |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your knowledge of adjectives.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section E: Adverbs

|

Modification |

Adjectives describe and classify but adverbs modify.

An adverb is usually defined as something like

a word which modifies a verb, an adjective or another adverb

Can you identify the adverbs in these examples?

- He came to the door quickly and I was soon enthusiastically welcomed.

- She frequently complains at length about things she thinks are really stupid.

- Please arrive early and put the food there.

- Wait outside until you are called.

- I can't go now but I'll go soon.

Click

![]() when you have answers.

when you have answers.

The adverbs are highlighted in black in the following:

- He came to the door quickly and I was soon enthusiastically welcomed.

- She frequently complains at length about things she thinks are really stupid.

- Please arrive early and put the food there.

- Wait outside until you are called.

- I can't go now but I'll go soon.

Some are easier to identify than others, aren't they? Adverbs in English do a number of different things.

- They answer the question

How?

quickly and enthusiastically in the first sentence are examples of these.

They are called Adverbs of manner. - They answer the question

When?

soon, now and early are examples of these.

They are called Adverbs of time. - They answer the question

Where?

there and outside are examples of these.

They are called Adverbs of place. - They answer the question How often?

frequently is an example of these.

They are called Adverbs of frequency (although some, including this site, prefer to call them a sub-set of adverbs of time). - They answer the question How much?

really is an example of this.

They are called Adverbs of degree.

If you think that at length is an adverb, you are half right. It does tell us about the verb and it does tell us how much or how she complains. However, technically speaking, it an adverbial, not an adverb because it is a prepositional phrase.

Try a mini-test to see if you can apply this to other examples. Use the Back button to return.

|

Recognising adverbs |

There are literally thousands of adverbs which end in -ly and very often that is what students are told is the defining characteristic but it can be misleading. If you see a word which ends in -ly, you may be tempted to classify it as an adverb. That is the way to bet but be careful of adjectives like friendly or wrinkly, verbs like sully and so on. If you want a long list of adjectives that look like adverbs, there is one here.

This works both ways. Not all words which are adverbs end

in -ly.

All of

the following can be adverbs and not one ends in -ly.

now, yesterday, next week, here, often, seldom, crabwise,

afterwards, beforehand

If you want to identify an adverb, the only safe way is to look at what it is doing.

|

What adverbs modify |

It's fairly clear (the clue's in the name) that adverbs modify verbs. What are they doing in these examples?

- He opened the box carefully.

- He is completely against the idea.

- That's a wonderfully simple solution.

- She speaks extremely intelligently.

Click

![]() when you have an answer.

when you have an answer.

- He opened the box carefully.

Here, the adverb carefully is doing the obvious thing. It is an adverb of manner telling us how he opened the box. Clearly, it's modifying the verb. - He is completely

against the idea.

Here, the adverb completely is doing something rather unusual. It is modifying the preposition against and tells how much against it he is. It's an adverb of degree. - That's a wonderfully

simple solution.

Here, the adverb wonderfully is modifying the adjective simple. Certain adverbs are frequently used like this and examples are very, absolutely, slightly, overly, totally etc. They are usually adverbs of degree. - She speaks extremely

intelligently.

Here, the adverb extremely is modifying another adverb, intelligently. We have an adverb of degree modifying an adverb of manner.

|

Adverb position |

One of the most vexing phenomena for learners of English is that adverbs are placed in sentences in a rather complicated manner. Look at the example sentences in this table and see if you can figure out some rules. Sentences which are considered wrong are marked with '*'. Then click on the table for some suggestions.

Look again at the examples. There is one

position where adverbs can never appear in English. What is

it?

Click

![]() when you have the answer.

when you have the answer.

Adverbs can never come between the verb and object.

We cannot say, therefore:

*She must tell always him

*He drove

carefully the car

*They saw everywhere it

*He enjoyed greatly the

play

*They have sold just their car.

|

Adverbs of frequency |

| He frequently smokes a pipe |

This category, a sub-category of time

adverbs, gets its own section because it is troublesome for learners.

There are two sorts of these adverbs:

-

Adverbs of definite frequency:

These refer to measurable amounts of time and include, for example:

I get the newspaper daily

She travels to London weekly

We meet annually

The normal position for these adverbs is at the end of a clause, after the verb, its object or any prepositional phrase.

Placing the adverbs anywhere else usually results in non-English or special emphasis.

Apart from annually and seasonally, these adverbs also functions as adjectives:

a monthly meeting

a yearly trip

a daily news broadcast

etc. -

Adverbs of indefinite frequency:

These refer to how often something happens but not in measurable terms. For example:

I seldom go to see her

vs.

I often go to see her

are comparably different but tell us nothing more than a rough idea of frequency. We do not know if the speaker means daily, monthly, annually or seasonally.

There are three issues with these adverbs:- Strength:

It is a traditional classroom practice to place these on a cline, like this:

but that's only a guide because native speakers will often disagree about where on the cline the adverbs occur. - Sentence type:

- Two of the adverbs do not usually occur in negative

sentences:

We accept:

I sometimes see my sister

Do you occasionally meet your brother in London?

but not:

*I don't sometimes see her

*She does not occasionally meet her brother - Four of these adverbs do not occur in questions or

negative sentences:

We accept

I hardly ever go to London

She scarcely ever asks for help

We seldom eat before seven

She rarely wants to eat out

but not, usually:

*Do you hardly ever go to London?

*I don't scarcely see her

*She didn't seldom eat out

*Does she rarely eat out?

etc. - Because never is a true negator, it cannot

occur in a negative sentence so we do not allow:

*We don't never arrive on time

but is does occur in questions as in, e.g.:

Do you never have breakfast?

- Two of the adverbs do not usually occur in negative

sentences:

- Position:

- All these frequency adverbs usually appear before

the main verb and after any auxiliary verb so, we

accept, e.g.:

I have seldom been to his house

We can scarcely ever take the early train

They sometimes work late

but not

*I have been seldom to his house

*We scarcely ever can take the early train

*They work sometimes late - They occur, however,

before semi-modal auxiliary verbs

She often has to come in early

She is often able to help me

They seldom used to entertain guests

They seldom dare to go - They always follow the verb be:

I am always late

She is never on time

They are scarcely ever helpful - The adverbs often, usually, sometimes and

occasionally can occur at the end of clauses:

They work late in the office sometimes

She comes to the house occasionally

He complains about having no money often

Others in this category can occur at the end of clauses but only with some special emphasis.

- All these frequency adverbs usually appear before

the main verb and after any auxiliary verb so, we

accept, e.g.:

- Strength:

Two adverbs of frequency are not in the lists above because they have special characteristics:

- generally

This is an adverb of frequency but it is difficult to place it on a cline because, for example:

He generally doesn't come to see me = He rarely comes to see me

She generally complains about the food = She usually complains about the food.

Do you generally eat early? = Do you usually eat early

So, in positive and interrogative sentences, the word means usually but in negatives, it means seldom or rarely. - ever

This is the positive form of never and occurs regularly in questions to elicit a statement of frequency:

Do you ever go to the cinema? Rarely, these days

It can also occur in negative sentences with the sense of never:

She doesn't ever wait for an answer

and is generally in the sense of a complaint.

As you can see, these adverbs have special characteristics which are not parallelled in other languages and cause, in particular, word-ordering problems for learners. Handle with care.

|

Fronting adverbs |

Most adverbs can be placed at the beginning

of clauses but doing so marks them for special emphasis in English.

In other languages, this is one of the normal positions for adverbs

and does not signify a special meaning.

When learners mistakenly place adverbs at the front of clauses,

therefore, they can give the wrong impression and a native speaker

of English may be puzzled about the emphasis which that position

implies.

Here are some examples of the four types of adverbs which can be

placed in the initial position:

Frequently, she works very late at the office

Daily, the rubbish is collected

Carefully, she climbed the ladder

Outside, they sat in the sunshine

and all these examples, mark the adverb as particularly important.

They are also, as you see, separated from the rest of the clause with a

comma.

Adverbs of place, used this way often imply a whole clause so the

last example may be equivalent to:

When they got outside, they sat in the

sunshine

However, we do not allow:

*Greatly, I liked the exhibition

*Slightly, she enjoyed the film

because:

Adverbs of degree can never be fronted.

It is not usually a very good idea to present fronted adverbs to learners at lower levels because the special emphasis which is implied may not be apparent to them.

|

Comparing adverbs |

Adjectives, as you know, can usually be modified two ways to show comparison or superlatives.

-

By adding -er and -est:

I'm older than her

She's the youngest in the family -

By using more and most:

The hotel was more expensive than I expected

That's the most beautiful painting

Adverbs are a little different because they are almost always

compared using more and most so we do not say, for

example:

*He drive slowlier than me

or

*She came quicklier than her brother

but say:

He drove more slowly than me

and

She came more quickly than her brother

However, there are two issues:

- Some short adverbs which do not end in -ly can be used with

-er and -est:

He worked harder than anyone else

She drove faster than I did.

The other common adverbs that take this form are: near, soon, late, early.

The adverb often can be used both ways informally but some people do not approve of oftener. - In colloquial speech, we often hear short adverbs being

modified like adjectives (but it is considered wrong by most

people):

The rain fell heavier

The sun shone brighter and brighter

In the classroom, the safest rule is that, apart from fast, soon, near, late, early and hard, adverbs should not be modified with -er and -est.

There are some irregular forms:

far > farther > farthest

ill > worse > worst

badly > worse > worst

well > better > best

little > less > least

much > more > most

|

Learn moreIf you want to discover more now about adverbs, go to: |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your knowledge of adverbs.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

A summary of content words

This diagram is taken from the in-service guide to word and

phrase class. You will see that pronouns, because they act

very much like nouns are included as a subcategory of them.

That is not an analysis accepted by everyone.

You can learn more about the various subcategories of the items by

following the links above.

Section F: What does mean mean?

|

Types of meaning |

This Unit concerns itself with lexical words and they are defined

here as words which, when they stand alone, carry a meaning that we

can define.

That's true but before we leave the area, we should be a little

clearer about what we mean when we say something like:

This word means ...

There are some issues in this area:

|

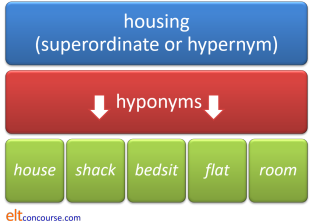

Synonyms and antonyms |

In a classroom, it is often tempting, because it is quick and

sometimes effective, to explain what a word means by saying

something like:

It means the same as ... (a synonym)

or

It means the opposite of ... (an

antonym)

|

A short task:

|

| happy | stupid | outside | mother |

| hide | inside | little | dim |

| tiny | conceal | sad | mummy |

| small | father | vast | clever |

| You may have something like this | |

| happy | can be seen as the opposite of

sad so they are antonyms but where does that leave

unhappy? We can say that: It was a happy coincidence but will you accept It was a sad coincidence? The issue here is that some words go together naturally and some don't. The technical term for this is collocation, incidentally. |

| hide | can be said to mean more or less

the same as conceal but hide can be

transitive and intransitive so we allow: I hid in the corner and I hid the present in the corner However, we can't say: I concealed in the corner and only accept I concealed the present in the corner These two words mean the same but they enter into different grammatical relationships. |

| tiny | is, on the face of it, the opposite

of vast. However, the words don't fill the

same slots in: She spoke in a ____________ voice She bought it at __________ expense Again, we have an issue of collocation. The adjectives cannot be used to describe the same nouns. |

| small | is often a clear synonym of

little but many people prefer the word small

because little is seen as rather childish.

The word little also carries the idea of attractive which

small does not. Compare: There was a small puppy in the house with There was a little puppy in the house When we use a comparative or superlative many will not like to say: It's a littler problem and prefer It's a smaller problem This is an aspect of meaning that we will make clear below. |

| stupid | is often, when applied to people,

the same in meaning as dim but, of course, we can

have: a dim memory but not: a stupid memory In other words, the word dim can be used metaphorically but the word stupid is not usually used that way. You may have thought that clever is a better antonym for stupid and that's right but it isn't the same as intelligent because you can't have: an intelligent trick in the same way that you can have a clever trick because the word clever often carries a rather negative meaning. This is an issue of connotation (of which more below). |

| inside | is clearly the opposite of

outside but we can have: an outside chance of success but not an inside chance of success so they are not always antonyms because they collocate differently. |

| father | is not really the opposite of

mother, is it? The word father obviously implies mother just as nurse implies patient and brother implies sister but they aren't antonyms in the same way that big and small are antonyms. |

| mummy | is generally considered children's

speak for mother although news programmes have

taken to using the word mum when they mean

mother. The words have very different styles. |

We have to be careful to know how a word is used, what it means to the speaker and what context it is used in.

There is a good argument that no pairs of words can be absolute synonyms because shades of meaning, grammatical forms or dialect use will always distinguish them. For example:

- sidewalk and pavement may be synonymous but the first is American dialect use and the second British dialect use

- determined and pig-headed may mean the same in some settings but the second is much more negative

- conceal and hide may have the same meaning but you can't say I concealed behind the curtain and you can say I hid behind the curtain.

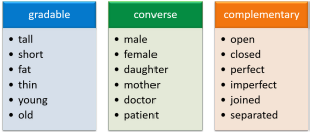

There are three types of antonymy which we considered above in the task:

- Gradable antonyms have meaning relative to each other. For example, a mouse is a tiny animal but huge compared to a microbe so tiny and huge are gradable antonyms.

- Converse antonyms imply their counterparts so a nurse implies a patient, inanimate implies animate and so on.

- Complementary antonyms become synonyms if you insert not before them. For example, clear and unclear become synonyms with the insertion of not (not clear = unclear, clear = not unclear). Other types of antonyms don't exhibit this because not male ≠ female (it could mean neuter) and not old ≠ young (it could mean middle aged, quite new and many other things).

|

Multiple meanings |

Almost half of the words in English have more than one meaning.

We saw in Unit 2, that a word such as clean can be both a

verb and an adjective but the word retains its basic meaning in both

word classes.

That is not the case for thousands of other words.

|

Another small task:

|

|

bank |

He fished

from the river bank

She took money from the bank I bank with them |

|

glasses |

I've lost

my glasses and can't see to drive

Do we have enough beer glasses? He was drunk after two or three glasses of whisky |

|

go |

Have another go

Go away! The car won't go |

|

blue |

She's looking a bit blue

A clear blue sky He's a blue collar worker |

|

doubtfully |

That is doubtfully correct

She looked at me doubtfully |

Two things are happening here:

- Homonymy

When a word has two unconnected meanings such as bank, which can mean the side of a river or a business which looks after people's money, then the words can be described as homonyms.

(The word homonym comes from the Greek for same name incidentally.)

The meanings are unconnected and probably derive from different sources (which is the case with the two meanings of bank).

When we convert the noun to verb as in the second two examples, we are simply converting the word class with no effect on meaning.

We also have a case of homonymy with two of the meanings of blue (the colour and the feeling of depression). - Polysemy

When a word has two meanings which are different but obviously connected in some way, they can be referred to as polysemes.

This is the case with glasses in this list. Clearly, in all three cases, the word refers to something made of glass but in the first case it means spectacles, in the second case it means containers made of glass and in the third case it means the contents of a glass.

The word doubtfully is also a case of polysemy because its meaning is altered in the two examples. In the first example it is modifying the adjective correct, toning it down and making it far less certain so it means something like only just possibly and in the second case it is modifying the verb and telling us how she looked and means something akin to sceptically. The uses cannot be reversed so we can't allow either:

*That is sceptically correct

or

*She looked at me only just possibly

The word go in this task is somewhere in the middle.

When it is a verb, it usually means something like move away

from a place but we can also use it to mean work or

function and we can convert it to a noun to mean try

or attempt.

Whether this is a case of the word having three homonyms or whether

you think the words are closely enough connected in meaning to be

considered polysemes is a debatable matter.

|

Three types of meaning |

When we try to answer the question, What does 'mean' mean?, we discover that we need to think about three types of meaning.

- Sense

This refers to a word's general significance.

For example, we can probably agree on the sense of the word coin. The word, as a noun, means a small metal unit of currency. This is the word's sense or its denotation. - Reference

This refers to the actual thing I mean (or the action etc. but for simplicity's sake, we'll focus on nouns). In other words, it is this instance of the word's use.

For example, if I say

The coin on the book

I know (and so do you) that I am referring not to coins in a general sense but to a particular one I have in mind. - Connotation

This refers to a second level of meaning above denotation and is often personally or culturally determined. For example, the lexemes earn and coin it in and the words quack and doctor carry the same senses (making money and a medical practitioner, respectively) but mean very different things. The same can be said of a whole range of lexemes such as youth-teen, child-brat, newspaper-rag, speech-sermon, dirt-filth, police officer-copper-cop and so on.

We saw this above with the uses of small (denoting only size) and little (denoting size and connoting attractiveness).

|

Idioms and fixed expressions |

| a needle in a haystack |

The issue here is called idiomaticity and the

example is of an idiom.

Idioms are frequently impossible to understand by knowing all the

words that make them up, a phenomenon known as non-compositionality.

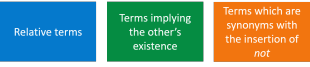

Here are some examples of idioms in English (on the left) and some

equivalents in other languages. Can you make them match?

Click on the image when you have an answer.

There are two important issues to describe concerning idioms in any language:

- Transparency:

It is sometimes possible to guess at the meaning, of course, and there is a range of idiomatic language from the completely obvious to the fully impenetrable.

For example:- she has missed the boat (meaning lost an opportunity) is just about comprehensible given some context

- they threw in the towel (meaning gave up or surrendered) is possible to understand if one has some knowledge of boxing conventions

- he kicked the bucket (meaning died) is wholly incomprehensible and must be learned and used as a complete unit

- Fixedness:

Some idioms cannot be altered at all (or only very slightly in terms of changing the tense or pronouns), but others can have multiple variants.

For example:- through thick and thin cannot be altered to through fat and thin or through thick and narrow and retain its meaning and is at the fixed end of the spectrum

- we're having a hoot can be expressed alternatively as we're having a whale of a time, and hit the sack can be replaced with hit the hay and so on. These are idioms with limited flexibility.

- Other expressions, which are really just strong

associations between words or collocations, are very much

more flexible (and don't count as idioms at all in some

analyses).

For example, we can make the beds, haste, friends and so on and on but not *make the homework, or *make damage (for which the verb do is preferred).

Similarly, we pay attention, a compliment and our respects but take an interest, offence, place etc. and give explanations, thanks and promises etc.

|

Learn more

semantics All these links are to the technical guides in the in-service section. |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your

knowledge of word meaning.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.

Section G: relationships between words

If we need to talk about the relationships between lexemes, we need to have some terms to talk about the ideas. Here they are:

|

Idea 1: Homophones and homographs |

We have already met words which have more than one meaning,

homonyms and polysemes, so now we need to look at words which look

the same or sound the same but have different meanings.

Clearly, in our example above, the word bank meaning a

financial business and the side of the river both look

the same (are spelled in the same way) and also sound the same (are

pronounced in the same way), but that is not always the case.

Many other words are homonyms of others so, for example, we may find

homonym pairs such as:

bat (hitting tool) and bat (flying animal)

down (lower) and down (feathers)

- dear and deer

- These words are written differently but pronounced the same

and have different meanings. They are

homophones. Other examples are:

hare-hair

right-rite-write

no-know

discreet-discrete - lead weight and lead an army

- These words are written the same but pronounced differently

and have different meanings. They are

homographs. Other examples are:

read (present tense) and read (past tense)

invalid (not usable) and invalid (sick person)

bass (a deep voice) and bass (a fish)

desert (leave one's duty) and desert (arid area)

export (the noun, stressed on the first syllable) and export (the verb, stressed on the second syllable)

tear (rip) and tear (drop of eye water)

|

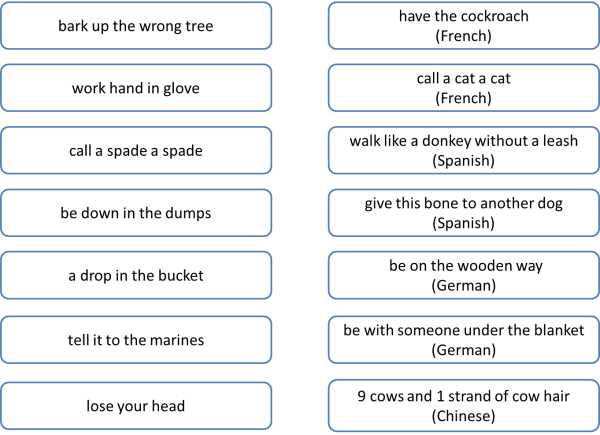

Idea 2: Hyponymy |

a relationship between words in which the meaning of one word includes the meaning of others which are closely related

The word derives from the Greek meanings of under and name.

- The superordinate or hypernym

- is the word which includes the meanings of all the others

- The hyponyms

- are all the second-level words which are related to each other

Like this:

|

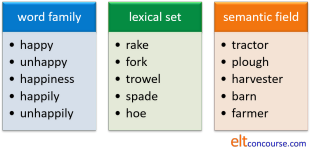

Idea 3: Word families, lexical sets and lexical fields |

On this site, the terms are defined like this because for teaching

purposes, it seems the most useful.

A word family refers to words with the same root.

A lexical set refers to words for objects (or verbs etc.) found in the

same conceptual area.

A lexical field refers to words of all kinds which occur in the same

topic.

Like this:

Lexical sets are usually defined as being words of the same class so we

could also have, e.g.

treat, care for, tend, operate, nurse, examine,

cure etc.

as verbs in a lexical set to do with health care.

|

Idea 4: Collocation |

Some words, as we saw above, go together, hand-in-hand, with other words, some don't.

So we have, for example:

torrential + rain

bright + sunshine

bitterly + cold

and so on.

Some words do not collocate so we can have:

strong winds and heavy snow

but not

*strong snow and heavy winds

and

tall people and high mountains

but not

*high people and tall mountains

Collocations can be analysed by:

- type:

- verb + noun (e.g., rent an apartment vs. rent / hire a car but not *hire an apartment)

- adjective + noun (e.g., nagging toothache, splitting headache but not *splitting toothache)

- adverb + adjective (e.g., deeply depressed but not *ecstatically unhappy, *shallowly depressed)

- noun + noun (e.g., cash dispenser, chocolate machine and cash machine but not *chocolate dispenser)

- verb + adverb (e.g., tiptoe quietly, shout loudly but not *walk violently or *shout softly)

- verb + preposition (e.g., rely on not *rely

by, burst out laughing but burst into

tears)

(Some do not allow this combination as a collocation, strictly speaking, because it is a grammatical issue.)

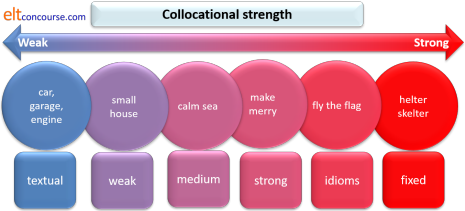

- strength:

- On the right we have fixed and semi-fixed idioms such as

the black sheep of the family (no word except sheep is allowed)

Here, too, we find two-word combinations (and sometimes three-word combinations) which occur in a fixed order, do not allow alternatives and carry a single significance such as

by and large

tall, dark and handsome

willy-nilly

etc. - Some collocations allow few other possibilities.

For example:

liquid assets or fixed assets

torrential rain or flood

rolling pin / stone / tobacco

There is a cline here, too, from strong to weak via medium strength collocations. Some allow a very wide range of possible terms but others are quite restricted. - The strength of a collocation is not usually reciprocal.

This means that, for example, while an adjective such as unpainted applies to a large but limited set of nouns (door, house, metal, railing, building etc.), the reverse is not the case and the number of adjectives which can be applied to a noun such as house is virtually unlimited. So, too, while the beds collocates with a very limited number of verbs (make is the only obvious one), the verb make will collocate with an extremely large number of nouns.

That is what is meant by non-reciprocity. - With textual collocations, certain words occur

conventionally together such as

doctors treat patients

nurses care for patients

police officers arrest people

firemen attend fires

and many other noun + verb + noun combinations are possible such as

solicitors advise clients

waiters serve diners

etc.

- On the right we have fixed and semi-fixed idioms such as

|

Learn moreThis link takes you to the in-service technical guide to word relationships and more. |

|

Take a test |

To make sure you have understood so far, try

a test of your

knowledge of word relationships.

Use the 'Back' button to return when you have done that.