Adverbs

Note: if you have not yet followed the guide to adjectives, some of what follows may be more difficult to understand.

This is quite a long guide as befits the discussion of a major word class so here's a menu of the parts it contains. At any time, clicking on -top- will return you to this menu.

|

Definitions |

|

Task: Easy questions: What's an adverb? What sorts of adverbs are there? (Hint: see if you can identify four.) Click here when you have answers. |

Usually people's definitions include something like 'a

word which modifies a verb'. That, as we shall see,

is only half right.

You may have come up with some (or all) of the following

types which in each case are verb modifiers:

- Adverbs of manner, answering the question 'How?'

so we get, e.g.:

He is cycling quickly

She is thinking hard

They are waiting patiently

etc. - Adverbs of place, answering the question 'Where?'

so we get, e.g.:

They are waiting outside

People were walking everywhere

Please sit here

etc. - Adverbs of time, answering the question 'When?' or

'How often?'

so we get, e.g.:

They are enjoying it now

I am going soon

She sometimes arrives late

etc. - Adverbs of degree, answering the question 'How

much?'

so we get, e.g.:

She enjoyed it enormously

They voted overwhelmingly for a change

He hated it intensely

etc.

You may have a slightly different list.

Some would put adverbs of frequency (sometimes, often,

frequently etc.) in their own category, some wouldn't. The

division between adverbs of manner and degree is also slightly

fuzzy. In fact, there are those who would argue that this sort

of categorisation lacks utility in terms of analysis but is useful

as a pedagogic tool only.

It ignores, for example, adverbs which perform different functions

like linking cause and effect (such as hereby) or

expressing the speaker's angle or attitude (such as economically

and theoretically).

Out here in the virtual world there are some other weird (and a few wonderful) classifications of adverbs which include invented and unsustainable categories such as causative adverbs, opinion adverbs and so on. We will not be inventing such things.

All the examples above are single words but adverbs also come as adverb phrases such as far more, from time to time, so very etc. They act as single-word adverbs in many cases but sometimes they have their own characteristics (see below). Some of these are better analysed as prepositional phrase adverbials but they perform parallel communicative functions.

(It

is worth a short aside here to distinguish between an adverb of

manner and an adverb intensifier. Adverbs of manner modify

verbs directly as in, e.g.:

She worked intensely

She thought deeply

She spoke bitterly

and so on.

However, a number of adverbs (including the ones exemplified here)

also act as adverb intensifiers in, e.g.:

It was an intensely painful wound

The idea was deeply misguided

She is bitterly opposed to the thought

Semantically and functionally, we should keep these concepts

separate or we risk confusing our learners unecessarily.

There is a guide to adverbial intensifiers, which are mostly

adverbs, linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

What's the difference between an adverbial and an adverb? |

This is where we get a bit technical. All adverbs are adverbials but not all adverbials are adverbs.

Any construction which modifies or describes a verb phrase is an adverbial.

Look at these four sentences

- He often arrived late.

- Mary spoke in German.

- They went on holiday last year.

- I came so that I could help with the cooking.

|

Two questions:

|

- Sentence 1

- contains a true adverb – often, which is an adverb of time, specifically, indefinite frequency.

- Sentence 2

- contains a prepositional phrase – in German which tells us something about the verb spoke.

- Sentence 3

- contains a noun phrase – last year which tells us something about the verb went.

- Sentence 4

- contains the subordinate adverbial clause – so that I could help with the cooking which also tells us something about the verb come (in this case, the reason for it).

This is important but in this guide, we are only concerned with adverbs. There is a separate guide to adverbials on this site, linked in the list at the end.

|

So what's an adverb? |

There are two fundamental sorts:

- adverbs functioning as adverbials (as in Sentence 1, above), for

example,

They left then

He spoke intelligibly - adverbs modifying adjectives and other adverbs, e.g.:

It's an extremely beautiful house

He spoke barely intelligibly

Adverbs can modify other parts of a clause, as we shall see.

|

Forming adverbs |

It is often the case that a word can be identified by its form as an adverb because English has only a few ways to form adverbs:

- The most common by far is the addition of -ly to the

adjective form (sometimes with a spelling change):

happy – happily, nasty – nastily, wooden – woodenly, rare – rarely etc.

This is the usual suffix for the formation of an adverb from an adjective in Modern English. Hence carefully from careful and hundreds of others. At one time, it was also the way to make an adjective from a noun (hence motherly from mother). The latter use has been replaced by a simple -y suffix.

It derives, however, from the Anglo-Saxon word lic or lich meaning body. The suffix has been shortened and grammaticalised to the suffix only. - For adjectives ending in -ic, the form is usually -ally

rather than just -ly:

comic – comically, specific – specifically etc. - Rarely, we can add -wards to other adverbs or nouns denote direction of

movement:

north – northwards, down – downwards, earth – earthwards, home – homewards, on – onwards, back – backwards etc. - Even more rarely, we can add -wise or -ways to

denote the manner of something:

crab – crabwise, edge – edgeways, edge – edgewise, coast – coastwise etc. - There is one example of an adverb formed with -long: headlong (and even that is usually an adjective). The adverb sidelong exists but the word is almost always adjectival.

- The suffix -wide also forms a rare set of words which are occasionally used as adverbs: nationwide, countrywide etc. When the suffix is attached to a nation or other state entity, it is usually hyphenated as in Germany-wide, Europe-wide, Japan-wide etc.

Unfortunately, an adverb is sometimes not identifiable from its form

at all and these words simply have to be learned individually because no

reliable form test is available to identify them. Examples include

many short place adverbials such as out, in, inside, over etc. as well

as ones such as seldom, often, outside, soon, home

and hard.

To complicate matters, some words can function in more than one way.

This is a phenomenon known as syntactical homonymy.

For example, in:

- He walked out

the word out is functioning as an adverb (of place or direction) but in:

He walked out the door

the word is functioning as a preposition with a noun-phrase complement (the door) but it is still part of an adverbial phrase.

Prepositions have complements, adverbs do not. - I want to go home

the word home is functioning adverbially, modifying go (or the whole verb phrase, want to go) but in

You have a lovely home

the word is functioning as a noun and is not adverbial in any way (and, incidentally, lovely is an adjective, although it looks like an adverb). - She arrived early

the word early is functioning as an adverb telling us about the verb arrive but in

We had an early breakfast

the word is functioning as an adjective.

As we see above, most adverbs are formed from or have equivalent

adjective forms. A few adverbs, however, notably:

just (meaning recently), quite, so,

soon, too and very

do not have any recognisable adjective forms at all.

|

Identifying adverbs |

We have see above that form is not a reliable basis on which to base the identification of word class. Adverbs may overwhelmingly be formed by the addition of -ly or -ally to an adjective but there are numerous exceptions and many adjectives look like adverbs because they end in -ly.

Meaning, too, is an unreliable guide because, although it is

fairly straightforward to focus on concepts encoded in words

relating to how a verb is performed, adverbs have numerous other

functions which are more difficult to pin down. We could, for

example, test for an adverb by asking whether the word refers to

manner, place, time or degree and that will often help us to

identify whether something is adverbial or not. It will not,

however, reliably

help us to identify an adverb because, as we saw above the class of

adverbials is much more varied than the class of adverbs.

For example, a word like more is certainly often an adverb

but it does not refer to manner, place, time or degree in the same

way that, for example, words like slowly, there, then and

greatly do.

Equally, in French, over the road, at six and with no

effort refer respectively to manner, place, time and degree yet

none is an adverb.

We are left, as is often the case, with a slot test which relies

on syntax as the defining characteristic. In other words, we

have to look at what the words do in the syntax of the language to

identify their word class.

This means identifying which words can fill certain slots in

clauses. For example, if you attempt to fill the slots in

these clauses with single words, you quickly discover that only one class

of words will do the trick:

She drove the car very __________ out of the garage

It __________ rains in England

She kicked the ball __________ over the wall

She did the work __________ well

It was a(n) __________ beautiful story

Adverbs.

|

Type a – adverbs as adverbials modifying the verb |

| The sun shone brightly |

When adverbs function as adverbials, modifying a verb or verb phrase, they are of three sorts:

- Adjuncts

- These are the most familiar ones to us because the adverb is integrated

into the sentence. We don't need any more information than the clause

contains to understand them. Some examples:

She waited inside

They told me quickly

She rarely gets here on time

I want to leave now

There are four adjunct adverbs in particular whose function is somewhat different from others. They serve to link cause and effect but do so in a way which makes the utterance perform the act. In other words, they are performative. They are also quite formal, even archaic.

Here are examples of the four most common ones:- You are hereby elected as captain

- The undersigned undertake herewith to transfer the money

- She had studied the area and was thereby able to explain it to me

- She sold the painting and therewith became quite wealthy

See the guide to cause and effect for a little more on this.

- Disjuncts

- These are not integrated into the clause (and are often

separated by commas) and they express the speaker / writer's view of

what is being said / written or they express how the speaker wants

the utterance to be viewed or the speaker's view of the truth or

generalisability of what is said. Some examples:

They are certainly not in

Obviously, he's not coming

Happily, I found my keys

Honestly, I have no idea

Because disjuncts are external to the clause structure and modify everything in the clause rather than a single element of it, they are sometimes called sentence adverbs and there is a guide to them on this site linked in the list of related guides at the end.

Many adverbs which appear as disjuncts are, in other contexts, adverbs of manner (see below).

Compare, for example:

She waited happily, sitting in the sunshine and reading her novel

where happily is an adverb of manner describing how she waited and applicable to the verb wait only

and

Happily, she waited for us and brought us home even though we were so late

where happily is a disjunct applicable to the whole of the rest of the utterance and which expresses the speaker's feeling. - Conjuncts

- These connect two separate and potentially independent clauses (they are, in fact,

cohesive devices and not, as some will call them, discourse markers). Some examples:

If the beer runs out, then I'm going home

He looked everywhere, yet he couldn't find her

I missed my bus. Consequently, I was late to work

Happily, this is not the place to discuss the technical difference between a conjunct and a conjunction but conjunct adverbs get their own section below.

|

Form, ordering and meanings for Type a |

Word order is sometimes problematic not least because languages differ.

Almost all adverbs

can be fronted for effect or emphasis:

Suddenly, it started to rain

Frequently, he tells lies

Carefully, he opened the box

Lately, I've been having nightmares

Adverbs of degree are not fronted. We do not find,

*Intensely,

he enjoyed the film.

We saw above that adverbs functioning as disjuncts and conjuncts often

appear initially in the clause but ordinary adjuncts can do so, too.

If you want to learn more, there's

a guide to fronting on this

site, linked in the list at the end. What follows applies to non-fronted adverbs.

|

Task: Before you go on, stop and decide where in the sentence the following adverbs can appear (apart from at the beginning): When you have done that, click here. |

| carefully | everywhere | slightly | tomorrow |

Try putting the adverbs into sentences such as:

|

| there | eventually | sometimes | intensely | |

| relentlessly | often | rarely | frequently | |

| soon | seldom | from time to time | now and then/again |

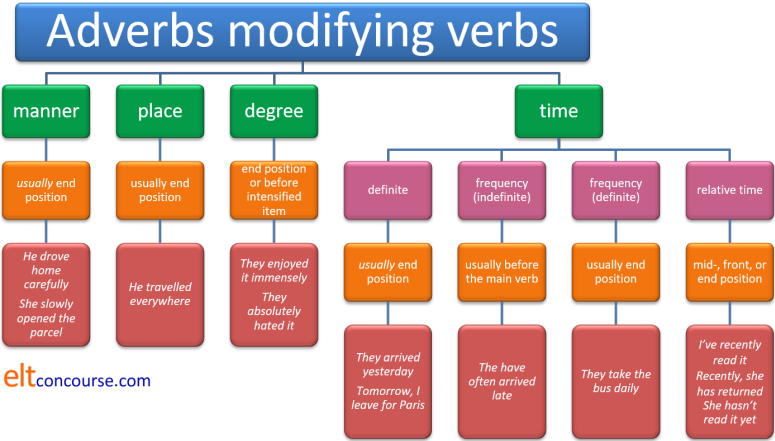

- Adverbs of manner (or process adverbs)

Usually, these follow the verb (if there's no object) or follow the object. So we get:

He drove carefully

He drove the car carefully

It is also possible, but rarer, to place these before the verb:

He carefully drove the car into the garage

But this won't work if the verb is used intransitively or with no prepositional or adverbial complement:

*He carefully drove

*She slowly walked

but

He carefully drove the bus out

She slowly walked away

They never come between the verb and the object:

*He drove carefully the car.

The traditional way to analyse these sorts of adverbs is, as we have here, to call them adverbs of manner. They are also called process adverbs because they can only apply to verbs which can be made progressive.

When adverbs such as carefully, slowly, quietly, stealthily, idiotically and so on are used with verbs in a stative meaning, the result is impossible. For example, we allow:

I played quietly

They arrived slowly

and so on, but we cannot have:

*I knew the answer carefully

*She saw the man slowly

*Peter believed she was silly quietly

because those are all stative uses on the verbs. Verbs which are normally stative can be used dynamically, of course and when that happens process adverbs may be used so we allow:

She was thinking carefully

I was considering the idea quietly

etc. - Adverbs of place

These, too, usually follow the object of the verb or the verb itself if there's no object. So we get:

He saw it everywhere

They went there

She came here

It is rare to front these, but possible for emphasis as in, e.g.:

Here she comes!

There they are!

They never come between the verb and the object:

*He saw everywhere friends

The ordering of adverbs of place in clauses generally mirrors the ordering of prepositional phrase adverbials which, for teaching purposes, is convenient because they are performing the same functions. - Adverbs of degree

These also follow the object (if there is one) or come directly after the verb. So we get:

She enjoyed the book slightly

He concentrated intensely

They pursued him relentlessly

These adverbs can be placed before the verb and this has the effect of making them slightly more emphatic. For example:

She greatly enjoyed the party

He completely finished the work

They never come between the verb and the object:

*They pursued relentlessly him

Into this category, we can also put adverb intensifiers (to which there is a separate guide on this site) such as completely, definitely, certainly, slightly, hugely and so on. These are of two sorts:- amplifying and downtoning adverbs which raise or lower the

scale of the verb they modify as in, e.g.:

She totally dismissed the idea

I'm afraid I have slightly scratched the car

etc.

Because these adverbs move the strength of the verb up or down a notch, they cannot be used with ungradable verbs (which are considered on or off events, by their nature having an end point) so we do not allow:

*She completely did her homework

*She slightly made dinner

*Peter somewhat travelled to London

*He wholly arrived

*John thoroughly found his wallet in the kitchen

etc.

but we can have:

She completely destroyed the garden

John thoroughly searched his pockets

Mary partially enjoyed the film

They wholly rejected the idea - emphasising adverbs, by contrast with amplifiers and

downtoners, may be used with almost any verb and serve to stress

it rather than increase or decrease the scale, e.g.:

They definitely arrived late

She has certainly lost her keys

She positively shouted with joy

I absolutely cried my eyes out

etc.

- amplifying and downtoning adverbs which raise or lower the

scale of the verb they modify as in, e.g.:

- Adverbs of time

There are four sorts of these:- Definite time adverbs usually come at the end of the clause. So we get:

I am leaving tomorrow

I want to leave soon

She arrived eventually

These are often fronted for emphasis. For example:

Tomorrow, I have to go shopping

Sooner or later, she'll get the message

In English, the fronted position marks the adverb for emphasis but in some languages, German and Spanish, for example, this is a common or compulsory position for the time adverb and carries no special marking.

Some analyses put words like home and tomorrow into the class of nouns acting adverbially. - Indefinite frequency adverbs

- These usually come before a main verb but after

any auxiliary verb (or the first auxiliary if there are more than

one) and after the verb be. So we get:

She often plays the piano

She has sometimes played the piano

He is frequently stupid

They would seldom have to ask for help

She rarely tells the truth

He will often have been there - These adverbs, however, occur

before semi-modal

auxiliary verbs

She often has to come in early

She is often able to help me

They seldom used to entertain guests

They seldom dare to go - The adverbs often, usually, sometimes and occasionally

frequently occur at the end of clauses:

They work late in the office sometimes

She comes to the house occasionally

He complains about having no money often

Others in this category can occur at the end of clauses but only with some special emphasis. - Multi-word adverb phrases of indefinite frequency do

not follow this rule.

With these the usual word order is to place them after the clause as

we do for other time adverbs. So,

we get:

He comes to my parties from time to time

not

*He comes from time to time to my parties

She only helps me now and then / again

not

*She only now and then / again helps me

There are two exceptions. The compound adverbs scarcely ever and hardly ever operate as single words and follow the same rules as often, seldom, frequently etc. so we get, e.g.:

She scarcely ever helps

The are hardly ever here

and neither can be placed terminally.

- These usually come before a main verb but after

any auxiliary verb (or the first auxiliary if there are more than

one) and after the verb be. So we get:

- Definite frequency adverbs usually

come in end position. For example:

I pay the paper bill monthly

They send electricity bills quarterly

These refer to measurable amounts of time and include, for example:

I get the newspaper daily

She travels to London weekly

We meet annually

The normal position for these adverbs is at the end of a clause, after the verb, its object or any prepositional phrase.

Placing the adverbs anywhere else usually results in non-English or special emphasis.

Apart from annually and seasonally, which are themselves derived from adjectives, these adverbs also functions as adjectives:

a monthly meeting

a yearly trip

a daily news broadcast

etc.

An adverbial phrase, such as once a month / day / year / summer etc. can be used instead of definite frequency adverbs but it is slightly more colloquial and in formal writing the adverb forms are preferred. - Relational time adverbs which connect two

times together. They often come in medial position, before

the main verb but also occur at the beginning and end of

clauses. For example:

She had already left when I arrived

She won't be at home yet

I have recently completed my degree

- Definite time adverbs usually come at the end of the clause. So we get:

|

Issues with adverbs of frequency and sentence types |

- Two of the positive adverbs, sometimes

and occasionally, do not occur in negative sentences:

We accept:

I sometimes see my sister

Do you occasionally meet your brother in London?

but not:

*I don't sometimes see her

*She does not occasionally meet her brother -

Two adverbs of indefinite frequency have special characteristics:

- generally

is an adverb of indefinite frequency but it is difficult to equate with others in the group because in positive and interrogative sentences, the word means usually but in negatives, it means seldom or rarely. For example:

He generally doesn't come to see me = He rarely comes to see me

She generally complains about the food = She usually complains about the food.

Do you generally eat early? = Do you usually eat early - ever

This is the non-assertive form of never and occurs regularly in questions to elicit a statement of frequency:

Do you ever go to the cinema? Rarely, these days

It can also occur in negative sentences with the sense of never:

She doesn't ever wait for an answer

and is generally in the sense of a complaint.

- generally

|

Negative-sense adverbs |

Six adverbs are semantically already

negative and are sometimes referred to as negator adverbs. They are: rarely, seldom, barely,

hardly, scarcely

and, of course, never.

Because these words are already negative in sense, they cannot be

negated again in the normal way.

Much more information about these, including some research findings

is available in the guide to negation, linked below.

Here, we will just set out a few examples of the general rules.

- These adverbs do not occur in questions or negative

sentences because their sense is already negative:

We accept:

I hardly ever go to London

She scarcely ever asks for help

We seldom eat before seven

She rarely complains about her work load

They never arrive on time

but not, usually:

*Do you hardly ever go to London?

*I don't scarcely ever see her

*She didn't seldom eat out

*We don't never arrive on time

*Does she rarely eat out?

etc.

(There are some doubtful areas of usage with these negative adverbs which are discussed more fully in the guide to negation, linked below.) - They are used with non-assertive forms (such as any,

ever, yet etc.):

- They rarely ever come to anyone's party

- I seldom went anywhere

- She barely saw anything

- They have hardly had any time to think yet

- She scarcely ever comes late

- She never has any time

- In the initial position, somewhat formally, they require

inversion of the subject and verb (with the do operator in past

simple and present simple forms):

- Rarely does he believe me

- Seldom have I heard such nonsense

- Barely audibly did she speak

- Hardly had I arrived when the phone rang

- Scarcely had she arrived than the fire alarm sounded

- Never have I seen someone make such a mess

- Like the negator never these adverbs can

take a positive question tag:

- They never like anything, do they?

- They scarcely said anything, did they?

- You seldom agree, do you?

- I hardly had time, did I?

- You rarely agree, don't you?

- I hardly had time, didn't I?

- It was barely audible, wasn't it?

- I never had much time, did I?

and we do not allow: - *I never had much time, didn't I?

Here's a summary which hides a good deal of detail but may be

useful to you:

|

Type b – adverbs modifying adjectives, adverbs and other parts of a sentence |

| The sun shone increasingly brightly |

|

Task: Try putting these adverbs: very unusually enough |

into these sentences: He has a good brain He drove carefully. Click here when you have done that. |

You

probably have:

He has a very good brain

He drove very carefully

He has an unusually good brain

He drove unusually carefully

He has a good enough brain

He drove carefully enough

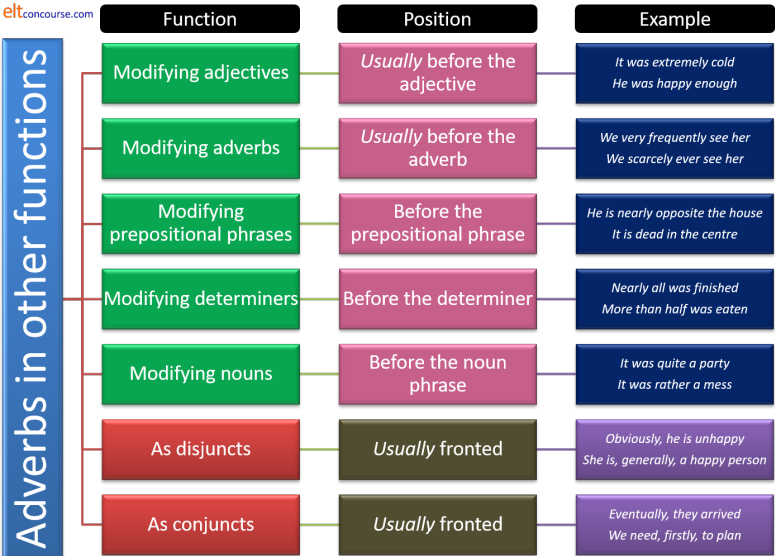

When adverbs modify an adjective or

an adverb (as many do) the odd-man-out is enough because it

follows rather than precedes the adjective or adverb. We get,

therefore, for example:

The answer is close

enough

I didn't do it carefully

enough

Otherwise, adverbs modify adjectives and other adverbs in

exactly the same way as they modify verbs. We can have, therefore:

That's very

interesting (modifying an adjective)

He opened the parcel

extremely carefully (modifying another adverb)

It is an important characteristic of the

adverb very that it can only modify another adverb or an

adjective. It cannot function as an adjunct and modify a verb

directly. It is not alone in this because other adverbs such as

extremely, utterly, slightly, exceptionally and so on also

function only to modify another adverb or an adjective.

Note, too, the post-modifying position of ever in, e.g.:

We hardly

ever

eat out.

The modifier ever is only used with indefinite frequency time adverbs so

We scarcely ever see him

refers to frequency but

I can scarcely see it

refers to manner and

I can scarcely ever see it

would be an unusual reference to frequency

because:

I can scarcely see it

is the only choice if we are focused on manner.

See also the guide to adverb

modifiers, linked below, which considers intensifiers: amplifiers,

emphasisers and downtoners.

A small class of adverbs is known as viewpoint adverbs because they serve to express the angle or viewpoint from which something is stated. They include the ones exemplified in:

- It was politically unwise to say that at the meeting

- It is ethically indefensible to suggest that

- It is technically feasible for the program to crash

- I am financially embarrassed

- His position is theoretically strong

In these examples, the adverbs are adjuncts because they function only to modify the adjective in each case but they can also function as disjuncts, modifying the entire clause as in, for example:

- Politically, it was unwise to say that at the meeting

- Ethically, it is indefensible to suggest that

- Technically it is feasible for the program to crash

etc.

and for more on that, you should consult the guide to adverbials and the guide to disjuncts, linked at the end.

|

Modifying adjectives vs. modifying adverbs |

Usually, adverbs which modify adjectives and other adverbs perform one of three functions which can all be described as intensifiers of some kind. Here are examples of the three types but there is a guide to adverb intensifiers on this site, linked below, which provides more detail.

- Intensifier: emphasising

- These adverbs simply make the modified element stronger.

They do not scale the item. For example:

She came really quickly

That was definitely better - Intensifier: amplifying

- These adverbs move the sense of the modified item up a

scale. For example:

That was very well done

The parcel was terribly heavy - Intensifier: downtoning

- These adverbs work in the opposite fashion, weakening the

intensity of the modified item. For example:

That was somewhat carelessly made

I thought he was quite nice

There is, however, an essential difference between those which can modify adjectives and those which modify other adverbs and it is this:

A range of adverbs can modify adjectives and retain their usual meaning but adverbs modifying other adverbs can only be intensifiers of some kind.

So, for example:

- We can have:

She was extremely tall

The figures were very carefully calculated

It was a pretty good party

That was quite surprisingly good

all of which are intensifiers of some kind, modifying either adjectives or other adverbs. - We also allow:

She was quietly confident

The novel was internationally admired

which are not intensifiers but retain their usual meaning when modifying adjectives. - But we do not allow:

*She spoke quietly angrily

*They worked internationally effectively

because adverbs which modify other adverbs are limited to one of the three intensifying functions. In other words, they must be intensifiers of some kind.

This is not a restriction, incidentally, which is parallelled in many other languages so it needs to be taught.

Three other adverbial expressions can pre-modify adverbs and adjectives:

- how

- shows the degree of the item. For example:

How heavily it had rained could be judged from the water in the pots

How heavy the rain had been could be judged from the water in the pots - however

- introduces a dependent adverbial clause. For example:

However angry she is, she shouldn't raise her voice

However hard he works, he gets no credit for it - so ... that

- so is a modifier followed by a that-clause

and means to the extent or degree. When it is fronted, it is followed by the

inversion of the subject and the do / does / did operator or

auxiliary verb. For example:

So carelessly did he drive that everyone was terrified

So fast did the bird fly that it was quickly out of sight

So much has she spent that she is completely broke

But the normal word-order rules apply when it occurs elsewhere in the clause as in:

He drove so carelessly that everyone was terrified

The bird flew so fast that it was quickly out of sight

She has spent so much that she is completely broke

(There is a somewhat rare, literary construction using so + an adverb which does not require the use of the do / does / did operator so we can encounter, for example:

So fast flew the bird that it was quickly out of sight

This formulation cannot, however, usually be used with a pronoun so we cannot allow:

?*So fast flew it that it was quickly out of sight.)

|

Adverbs modifying other sentence elements |

- Some adverbs can modify prepositions or prepositional phrases.

E.g.:

She's dead against the idea

The bullet went completely through the metal

The wind blew clean through my thin jacket

They are (very) nearly over the worst

It is just next to the post office, directly opposite the station

They live right by the river

Was nearly after dark when they arrived

It was way over my head

The meeting started shortly after 6 o'clock.

The man spoke purely in his own interests.

They acted solely to their own advantage

That's a comment very much out of order here.

We looked all over the town for a replacement.

That is, by the way, virtually a complete list of adverbs that act this way. - A more limited range of adverbs can modify the adverb particles

of phrasal verbs so we allow, for example:

She hit right on the solution

The anaesthetic has worn well off

but this is quite rare and most modification of adverb particles produces malformed language so we cannot allow, e.g.:

*The arrangement feel immediately through

*She gave completely in

*She turned the job straight away down

so the modifier needs to be placed outside the phrasal verb as in:

The arrangement immediately fell through

She gave in completely

She turned the job down straight away - Adverbs may modify determiners, indefinite pronouns and numerals. E.g.:

Almost everyone came back safely

More than 20 people came late

Nearly 600 guests were invited - A few adverbs (such, rather, quite) can pre-modify nouns and

noun phrases. E.g.:

That's quite a job.

It was such idiocy

The kitchen's rather a slum

Some adverbs can also modify a noun directly, acting adjectivally:

An away match

The above paragraph

The then teacher of French

The upstairs bedrooms

The home journey

The backstage party

Syntactical homonymy may be considered here and the alternative analysis is to consider that these words can be adverbs or adjectives depending on their grammatical function. - Many adverbs can post-modify noun phrases and

they are of two sorts:

- Time adverbs:

The party yesterday

The meeting afterwards

The argument beforehand

His sleeplessness overnight

The adverbs daytime, nighttime and overnight can all be used as pre-modifiers but they may better be considered as adjectives when they do that as in:

His daytime thought

Her nighttime worries

My overnight trip - Place adverbs

My journey overseas

His way home

That child there

This customer here

The road ahead

Only a few of these can act either as pre-modifiers or as post-modifiers. They are: upstairs, downstairs, home and above. Non-intuitively, below can only be used as a post-modifier so, e.g.

*the below paragraph

is not allowed but

the paragraph below

the above paragraph

and

the paragraph above

are acceptable.

Again, especially when they pre-modify, some can be considered adjectives so in

an upstairs room

the word upstairs is adjectival rather than adverbial.

- Time adverbs:

|

Making a distinction: two types of adverbs |

There is another way to classify adverbs on a less structural and more functional basis. There is a guide to circumstances linked in the list of related guides at the end and the analysis is akin to what you will find there.

- Circumstantial adverbs:

Where?

When?

How? - An adverb which answers any of these questions is a

circumstantial adverb. For example:

I stayed there (a place adverb)

He came early (a time adverbial)

He walked fast (a manner adverb)

As you can see, this classification applies to type-a adverbs analysed above.

Circumstantial adverbs generally modify verb phrases. - Additives, Exclusives, and Particularisers:

Including what?

Excluding what?

Focused on what? - These adverbs perform one of three functions:

- As additives, they act to join items

together and signal that they are equally important.

In this way, they often function as conjuncts. For example:- John's ideas are very important. Mary

also has

a good point, I believe.

Here, the adverb also functions to alert the hearer / reader to the fact that both ideas are to be considered on a par and of equal standing - I went to London. I met Mary,

too.

Here, the adverb too signals that both events are of equal importance. There is no sense of subordination. - Mary is both a brilliant cook and a wonderful

dancer.

Here the adverb both plays the same equalising and additive role.

- John's ideas are very important. Mary

also has

a good point, I believe.

- As exclusives, they serve to signal that

some events or states are not to be considered.

These are also called restrictive adverbs because they function to limit what it is we are saying to a particular context. For example:- This meeting is called solely

to consider the future

of the library.

Here, the adverb solely signals that no other discussion is appropriate. - This is just a question of knowing how to work the

machine.

Here, the adverb just signals that no other information is necessary, thus excluding, e.g., guesswork and trial and error. - I am merely at this meeting to take notes and report

back.

Here, the adverb merely excludes any other possible role for attending the meeting. The adverbs simply or only could be substituted with little change to the meaning.

- This meeting is called solely

to consider the future

of the library.

- As particularisers, adverbs can signal the

speaker / writer's focus.

They are often to be found in the initial position for emphasis and are frequently viewpoint adjuncts signalling the angle from which the speaker is working. They can also be disjuncts signalling the speaker's view concerning how a whole statement should be understood. In some analyses, these are called sentence adverbials because their function is to modify the whole clause, not only the verb or verb phrase.

For example:- These birds are mostly

found near fresh water.

Here, the adverb mostly, in contrast to an exclusive such as only, serves to focus on water in particular but also signals that other habitats are possible. - She is generally good at liaising with customers.

Here, the adverb generally signals the fact that there are other possibilities but the focus is on the fact that she is good at liaison.

As a disjunct, the word can signal the limitations the speaker is placing on how one should understand what is said. For example:

Generally, this is a good piece of work with much to recommend it

where the disjunct signals the speaker's wish to be understood as commenting with the restriction that what is said does not apply to the whole piece of work. - Predominately, the course will focus on English for

Academic Purposes.

Here, the adverb predominately serves a similar focusing function without excluding other elements of the course.

- These birds are mostly

found near fresh water.

- As additives, they act to join items

together and signal that they are equally important.

|

Adverbs as conjuncts |

We saw above that many adverbs can act as linking items,

connecting ideas and making texts cohesive. The discoursal

function of some adverbs is often overlooked if people focus only on

those which modify verb phrases.

Conjuncts usually function anaphorically, linking a clause or

sentence to a preceding clause or sentence.

When adverbs function as conjuncts, they are often preceded by

conjunctions, often but not exclusively, coordinators.

For example:

She missed her train and,

consequently,

couldn't attend the wedding

They lost their keys so, therefore, had to break in

I can drive you to the station but,

alternatively, there's a

bus from the corner

She was a wealthy person although,

additionally, somewhat

mean-spirited

Here are some examples of what they do. For more, see the

guide to conjuncts listed in the list of related guides at the end.

In that guide 11 functions are identified but we'll simplify things

slightly here because, for teaching purposes, some functions can be

handled together and adverbs themselves do not function in all the

categories, some being the domain of prepositional phrases or

clauses.

In the following examples, we have omitted the first clause or

sentence but it can be easily imagined.

- Listing and enumerating:

Secondly, we come to the matter of finance.

Next, we need to consider possible problems - Adding

Additionally, there is the question of who should be invited

Furthermore, he didn't write to thank us. - Summing up

Briefly, this means we will have to start again

Concisely, the problem is twofold - Showing result

Consequently, he became very ill

Accordingly, she attended the meeting in person - Contrasting

Alternatively, you can stay here and I'll go shopping

Otherwise, we'll be too late to get the tickets - Equating

Similarly, she is very determined to go.

Equally, the problem is solvable - Topic switching (or signalling return to a previous topic)

These are sometimes referred to as transitional conjuncts.

Anyway, what have you been doing recently?

Anyhow, how did he do? - Expressing time

Eventually, she agreed

Later, we all went along with the idea

As the examples show, conjunct adverbs are almost always fronted

in the second clause or sentence (as a consequence of their

anaphoric discourse role) but, often quite formally, they can be

inserted in the clause or take the end position, as in, e.g.:

We arrive, finally, at the main item on the agenda

She, consequently, arrived late at the meeting

They saved their money, accordingly

This problem is, equally, quite serious

|

Error alert |

If the adverb is not separated by commas or by pausing between

separate tone units from the rest of the clause, then some ambiguity

arises. For example:

Her husband was displeased and she ended up similarly unhappy

means that we are comparing her unhappiness with

her husband's displeasure so the adverb is only modifying the adjective,

acting as an adjunct, which is commonly what adverbs do. However,

Her husband became displeased and she ended up, similarly, unhappy

betokens that we are comparing her ending up unhappy with her

husband's becoming displeased and

the adverb is functioning as a conjunct linking the whole second

clause to the first.

Another example may help.

In:

That's what the boss said is vital but this is equally

important

the adverb is modifying only the adjective important and

equating it to vital. However, in:

That's what the boss said is vital but this

is, equally, important

the adverb is linking the whole sentence to a previous one and

implies that the boss saw both things as vital.

Fronting the adverbs removes the danger of ambiguity so the adverbs

in:

Her husband became displeased. Similarly, she ended up unhappy

The boss said that is vital. Equally,

this is important

are only interpretable as conjuncts.

Here's another summary of the other functions of adverbs which, again, hides a good deal of detail.

|

Adverbs as complements of prepositionsNo, that's a compliment. |

On this site, we avoid, generally, the use of the term

prepositional object, preferring to talk of prepositional

complements so, by our definition, the noun phrase the mainline

railway station is, in:

We arrived at the mainline railway station

the complement of the preposition at.

Some analyses prefer to use the term prepositional object for it

because that is how the noun phrase is acting. So be it.

Adverbs of time and place (only) often act as prepositional

complements, however, and, in that case, cannot sensibly be

described as objects because they are not noun phrases and the

object of anything is normally a noun of some type.

|

Adverbs of place |

- The place adverbs, here and there,

co-occur with a range of prepositions including: along,

around, down, from, in, near out, over, round, through, under

and up, so we get phrases such as:

along there

from there

out there

through here

up there

etc. - The place adverb home also occurs with a more

limited range of prepositions:

at home

near home

from home

towards home

etc. - The preposition from is particularly productive (or

promiscuous) and can co-occur with a large range of place

adverbs, for example:

from above

from abroad

from outside

from indoors

from within

and many more.

|

Adverbs of time |

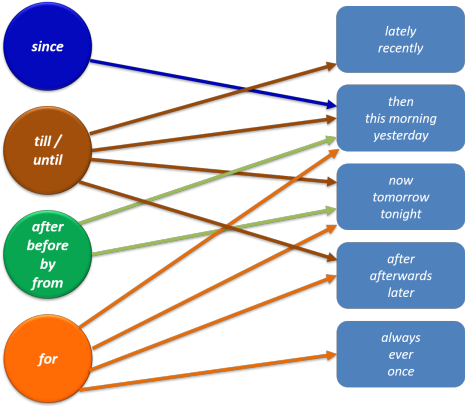

The co-occurrence of prepositions and time adverbs is quite restricted and a good example of the overlap between grammatical and lexical collocation. The picture is:

Adapted from Quirk, et al, 1972:283

To explain this rather complicated diagram:

- The preposition since will take the time adverbs

then, today, and yesterday as

complements but will not collocate with any of the other adverbs

except, slightly arguably, tonight.

We allow, therefore:

He has lived here since then

She has worked on it since yesterday

but we do not allow, for example:

*He lived there since afterwards

*She did it since once

or any of the other adverbial complements.

(Quirk et al include lately and recently as possible complements of the preposition since. Others, including this site, do not find that convincing so assume that, e.g.:

*He has been here since lately

is, in fact, malformed or at least very rare.) - The preposition till/until will take many more

adverb complements (all in the first 4 rectangles on the right).

We allow, therefore:

Until recently, I didn't understand his position

He stayed until this morning

I have driven till now

They didn't meet until afterwards

but we do not allow, for example:

*He'll stay till always

*She did until ever - The prepositions after, before, by and from

are more restricted and only take then, today, yesterday,

now, tomorrow and tonight as their complements.

We allow, therefore:

He lived here after then

She has eaten it before now

It'll be done by then

From then, he was more careful

but we do not allow, for example:

*He lived there before lately

*She did it by afterwards

*He was here after once

or any of the other adverbial complements. - The preposition for is less restricted and takes

all the adverbs except lately and recently as

complements.

We allow, therefore:

It's enough for this morning

He's staying for tonight

I'll keep it for later

We'll treasure it for ever

but we do not allow, for example:

*He lived for recently

Of course, not all the prepositions on the left will collocate naturally with the adverbs on the right, but most will.

In other languages, naturally, the restrictions set out here do

not apply or are different and first-language interference can lead

to errors such as:

*Before recently, I didn't know that

*I will stay until always

*From later we stayed indoors

*Since now he won't arrive

etc.

|

Negating adverbs |

In English, negation usually begins with the negator and continues to the end

of the clause so what comes before the negator is left in peace.

For example:

He didn't go frequently = He went sometimes

but

He frequently didn't go = He often failed to go

Where the adverb is positioned in a negative sentence is, therefore,

critical to how it is understood.

As we see from this example, there is a word-ordering issue with

some time adverbs when they are negated. The usual position

for adverbs of indefinite frequency such as always, often,

sometimes, occasionally etc. is to place them between any

auxiliary verbs and the main verb so we accept, e.g.:

She has frequently arrived late

I sometimes go to his parties

but reject:

*She has arrived frequently late

*I go sometimes to his parties

However, when the sentence is negated, a different ordering is often

apparent so we accept:

She hasn't frequently arrived late

She didn't frequently arrive late

and we can also accept:

I don't go to his parties sometimes

and probably reject:

*I don't sometimes go to his parties

Above and elsewhere on this site, it is suggested that neither sometimes nor occasionally occur in negative clauses. That is usually true but as we see above, not universally so.

The same consideration applies when the adverb is modifying other

elements. For example:

Not only Mary will be late = Other people will also be late

but

Mary will not only be late = She will also do something else

(such as complain about something)

|

Comparatives and superlatives of adverbs |

There are exceptions but for most adverbs the rule generally is that we use the

periphrastic constructions with more and most or

less and least to make

the comparative and superlative forms with adverbs, especially those ending in -ly, so we have:

I go more often than I used to not (usually) ?oftener

I go less often than I used to

She was more deeply affected

not *deeplier

Her sister was the least deeply affected

and so on.

For a longer discussion of inflexion vs. periphrastic forms, see the

guide to adjectives.

In very informal (wrong?) uses, we also find adjectives taking the place

of two-syllable (disyllabic) adverbs in clauses such as

?He drove quicker

This

really should be more quickly, of course.

Would you accept any of these?

He spoke slower

He dressed scruffier

She answered happier

Not all adverbs can be modified to form comparatives and

superlatives.

There are, for example, no comparative forms of adverbs of place

*I waited inside but he

stayed more inside

Adverbs of direction can be modified but not with the more/most

construction. Instead the preferred modifier is further

as in, e.g.:

We drove further northwards

They went further inside

but not:

*The went more downwards

*She travelled more westwards

*They went more outside

*She travelled more away

etc.

This is non-intuitive for speakers of many languages which do allow

such modifications and a source of quite persistent, if rare, error.

Not all adverbs of time can be modified so while we can have, for

example:

She frequently works late but

her boss more frequently does so

She came late but I came

even later

because these refer to indefinite frequency and are by definition

gradable.

We cannot, however, make comparatives or superlatives with adverbs of absolute

time as in

She's working tomorrow

John arrived eventually

I have started already

because

*more tomorrow, *more eventually and *more already are

not available.

We can also not make comparatives and superlatives with adverbs of

definite frequency because *more seasonally, *more yearly, *less

daily etc. are not available, either.

Some uncommon adverbs are formed with wise, ward(s) and

ways and these are usually, for semantic reasons,

ungradable. However, the -wards series can be graded

as we saw with further to give, e.g.

He pulled it

further upwards

They continued further homewards

|

Exceptions |

- Some adverbs retain the same form as the adjective and for these

we use the same rules as the adjectives follow so we have:

He drove fast – She drove faster

He worked hard – She worked harder

She arrived early – He arrived earlier

He spoke too long – She spoke even longer

He came late – She came later

To that list, in informal English, we can add a few very common adjectives which, in the comparative forms can act as adverbs so we hear:

They bought it cheaper than they thought possible

He played the music louder and louder

and, perhaps:

?He just drove quicker - Some adverbs are irregular so we have:

He drove well – She drove better/the best

He drove far – She drove further/farther

He drove badly – She drove worse

(More badly is heard in some varieties of English especially if it is pre-modified with even so we can have:

I played even more badly than I usually do.) - The adverb soon has no adjective form and we get: soon-sooner-soonest.

|

Pre-modification |

As is the case with adjectives, comparative and superlative forms

of adverbs may themselves be pre-modified, either to amplify the

sense or tone it down so we find, for example:

He came much sooner than I expected

He did it a lot less carefully than he should

She worked far more carefully after that

He needs to work a damn sight harder

He walked rather carefully on the ice

They came a little later than we hoped

etc.

|

Two oddities |

There are two adverbs, hardly and scarcely,

which differ in meaning from the adjectives from which it appears they

are derived. Both these are commonly post-modified with another

adverb, ever, only if the sense is habitual.

For example:

We hardly (ever) go to the cinema

I can scarcely (ever) trust him

When the sense is non-habitual but refers to current ability, the

modifier is not permitted:

*My eyesight is poor and I can scarcely ever read this

*We can hardly ever accept this price

These two adverbs have no corresponding comparative and superlative

forms at all so expressions such as:

*We more hardly go there these days

*I can more scarcely understand that

are not available.

Both adverbs are negative in sense and therefore associated with

non-assertive forms of pronouns, determiners and other adverbs so we get, for

example:

We hardly have

any whisky

not

*We hardly have

some whisky

and

I've scarcely started

yet

not

*I've scarcely started

already

|

Adverbs in multi-word verbs |

Multi-word verbs come in a variety of flavours and shades but one essential way to classify them is to consider whether the particle is an adverb or a preposition. In the first case, they are classifiable as phrasal verbs and the second as prepositional verbs. This matters because the structures of the clauses in which they occur vary considerably depending on the grammatical function of the particle.

There is a good deal more about this in the guide to multi-word verbs,

linked in the list at the end. Here is will suffice to consider

how the adverbs work when paired with a verb. Adverbs, as we know,

modify verbs but prepositions act to link the verb with its object.

So, for example, in

She is looking at the sky

the particle at is a preposition as it usually is and it acts

to link the verb look with the object, the sky.

The preposition does not affect the meaning of the verb look in any way

and we can also have, for example:

She is looking through the window

She is looking towards the door

She is looking under the newspaper

She is looking in the fridge

and so on. Equally, we can change the verb to a close synonym

while keeping the preposition and the meaning remains unchanged so

we can have, e.g.:

She is staring at the sky

She is gazing at the sky

She is peering at the sky

and so on.

However, other particles are more frequently found both as

prepositions and as adverbs with no change in form. For example:

The word up can be a preposition as in, e.g.:

She walked up the stairs

and it can be an adverb, as in:

She woke up the cat

etc.

Other words which can function as both prepositions and adverbs include:

around, down, in, off, on, out, over, round. Another name for

the phenomenon of words sliding between classes is categorical

indeterminacy, by the way.

Briefly, we can apply two tests to work out what role the lexemes are playing and that will help us to define our terms and teach the area consistently and accessibly:

|

The distinguishing point is that adverbial particles combine with the

verb to make a new meaning but prepositional particles simply link the

verb with its object although the meaning of the verb may be a

metaphorical use such as:

He stuck at his work

They talked around the main issue

etc.

Because the combination of verb + adverb results in a new and often

unpredictable meaning, the item is best learned and produced as a single

lexeme which can often be separated with the object interposed as in,

e.g.:

She looked the word up on the internet.

The test is to see what happens when we change the particle word so, we allow:

She walked down the stairs

She walked through the park

She walked over the bridge

She walked in the village

etc. but, if we change up to anything else in the second example, we get

nonsense:

*She woke down the cat

*She woke through the cat

*She woke over the cat

*She woke in the cat

|

A second test for whether a word is acting as a preposition or an

adverb is to give it a complement (or object, if you prefer).

Prepositions take complements (or objects), adverbs do not. So,

for example:

She passed by the church on her way

is a case of a preposition, by, taking the complement (or

object) the church to form a prepositional phrase and the

preposition on taking as its complement the noun phrase her

way. We could also have:

She passed in front of my house during her journey

She passed along the riverside on her tour

Here the structure is:

verb + prepositional phrase(s).

However, when we consider:

She passed up the chance

we have up functioning as an adverb, changing the meaning of

the verb pass from go by to deny oneself, because the

structure is:

phrasal verb + direct object

and in this case, the verb is not pass, it is pass up

as can immediately be seen if one replaces the adverb with another:

She passed over her ID card

where the adverb is combining with the verb to make new meanings (surrender

or transfer).

|

Resisting temptation |

The temptation is, however, to categorise all verbs which are

followed by adverbs as phrasal verbs and encourage learners to commit

them to memory as single concepts. This is mistaken because in

many cases the adverb is simply functioning to modify the verb rather

than combining with it to make a new meaning.

In some sources, then, one finds such expressions as: call back, get

on, get off, go ahead, run after, walk around and a host of others

described as phrasal verbs. They are in fact no such thing; they

are just verbs followed by modifying adverbs and that becomes clear when

we replace the verb with a near synonym or replace the adverb with

another. So we can have, for example:

I called him back

I phoned him back

I texted him back

just as we can have:

I called him later

I phoned him again

I texted him frequently

and so on. The sense of the verb in all cases is unchanged by the

choice of adverb.

A notorious case concerns the expressions get on and get

off (e.g. a bus) which are often described as phrasal

verbs. They aren't really because we can apply the same test and

replace the adverb or the verb so we can have:

She got off

She stepped off

She jumped off

She hopped off

or

She got on

She got in

She got out

She got away

So, asking learners to consider learning these as fixed expressions is

not a good use of their time. A better use is to take the time to

learn the meaning of the adverbs and that is often parallel to the

meaning the word has when it is used as a preposition. It is a

short step from understanding

She took the paper off the table

where off is a preposition, to understanding

She got off near her house

where off is an adverb,

because both refer to movement away from.

It is even asserted (out here on the web but rarely in serious reference

resources) that sit down is a phrasal verb. It isn't of

course, because we can also have:

sit up

sit back

sit forward

sit still

and so on and in all cases the verb retains its simple meaning but

the manner of it is modified by the following adverb.

There is more about this fallacy in the guide to multi-word verbs.

|

Adjectives masquerading as adverbs |

In many varieties of English, including some British

dialects, it is informally acceptable to use an adjective where a

purist would demand an adverb. We hear and read, therefore,

e.g.:

He ran quick

She explained clear

It burnt bright

She was hurt bad

They looked close

and so on.

Such uses are quite common in AmE (and much bemoaned by some

American writers). In British English, especially in some

dialect forms, uses such as:

We don't speak proper round here

or

Speak nice to your grandma

are also common.

Even in more formal English, some uses of adjectives where an adverb

would be technically required are seen and heard as in, for example:

Come quick!

She arrived as quick as she could

They were hurt quite bad

I looked closer

She copied it near perfect

He was sore afraid

(Historically, the separation of adverbs from adjectives was not rigidly made until well after Shakespeare's time and word classes of all sorts were much more fluid. When people began to attempt to codify the language some recommended a distinction, for example, between the preposition toward and the adverb towards (only the latter survives commonly as a preposition). The recommendation, too, was to make a distinction between the adverb forwards and the adjective forward (and both are now routinely used as adverbs while forward as an adjective is somewhat rare and akin in meaning to impertinent or unashamed)).

|

Proleptic adjective use |

Purists should not take their insistence on the

adjective-adverb distinction too far. Consider, for example:

Hammer the iron repeatedly

Hammer the iron flat

In the first, we have the normal adverb modifying the verb

hammer, of course, and none would complain about the rightness

of the use. However, in the second, few would suggest that the

word should be flatly as in, for example:

He flatly refused to help

What we have here is an example of a proleptic use of an adjective,

not an adjective masquerading as an adverb at all. Proleptic

means, roughly speaking, anticipatory and proleptic use implies that we are considering the end

effect, not the current action. In other words, the adjective is

modifying the noun iron (as is the proper role of adjectives), not the

verb. Other examples of such uses are:

Play the music loud

Roll the pastry smooth

Pull the rope tight

in which the adjective is being used to modify the music, pastry

and

rope, respectively and not modifying the verb. Compare:

Play the music loudly

Roll the pastry smoothly

Pull the rope tightly

in which the adverb is preferred because it is the verb (manner)

which we wish to modify.

|

Adjectives which look like (or act like) adverbs |

Some adjectives, it was noted above, look like adverbs and

this betrays their origin. For example, the adjective friendly

looks very much like an adverb with its -ly ending and gives

rise to the awkward expression friendlily as its parallel

adverb.

Originally, the word derives from Old English freondliche, and

the -che inflexion was lost later so the word now functions

only as an adjective having passed through a phase in which it performed

both roles.

The word seemly, for example, has a similar route into modern English and now

the -ly inflexion is routinely used to make adverbs and

the suffix -y to make adjectives.

Here's a short list of adjectives which look like adverbs and cause some awkwardness when we try to form the corresponding adverb. Many will not accept the unattractive forms such as livelily, measlily and so on.

| beastly bodily brambly bristly brotherly bubbly burly chilly comely comradely costly courtly cowardly crackly crawly crinkly crumbly cuddly curly daily dastardly deadly deathly disorderly drizzly early earthly easterly elderly |

fatherly fiddly fortnightly friendly frilly gangly gentlemanly ghastly ghostly giggly girly godly goodly gravelly grisly grizzly heavenly hilly holy homely hourly jolly kindly kingly knobbly leisurely likely lively lonely |

lovely lowly maidenly manly mannerly masterly matronly measly melancholy miserly monthly motherly muscly neighbourly nightly niggardly northerly oily orderly pally pearly pebbly poorly portly prickly priestly princely quarterly queenly |

saintly scaly scholarly seemly shapely shelly shingly sickly silly sisterly slovenly smelly soldierly southerly southerly sparkly spindly sprightly squally squiggly stately steely straggly stubbly surly thistly tickly timely treacly |

ugly unearthly unfriendly ungainly ungentlemanly ungodly unholy unkindly unlikely unlovely unmannerly unmanly unruly unseemly unsightly untimely unworldly weekly westerly wifely wily wobbly womanly woolly worldly wriggly wrinkly writerly yearly |

Many of these words are the result of conventional -y suffixation to form an adjective from a verb or noun with the word from which they are formed happening to end in -l or -le. Nonce words, such as jungly or tangly, may often be formed this way because the -y suffix is still very productive in the formation of adjectives from nouns.

All adjectives referring to definite frequency in this list are also adverbial

so we allow both, e.g.:

We had an hourly meeting

and

We met hourly

The words seasonally and annually do not work

in this way, being confined to adverb status, derived from the

adjectives seasonal and annual.

The adverb early also functions as an adjective so we

can have:

We had an early breakfast

and

We ate breakfast early

The words kindly and unkindly are both adverbs

formed from the adjective kind but also, confusingly,

operate as adjectives so we allow, e.g.:

He spoke kindly / unkindly

and

He was a kindly / unkindly man

Adverbs formed from such adjectives are so unappealing to many

that the preferred adverbial expression will be something like:

in a(n) [adjective]

manner / way. For example:

She spoke to me in a friendly way

not

She spoke to me friendlily

If you would like that list as a PDF document, click here.

A few adjective-adverb forms are identical and the list includes

hard and fast so we find:

It's a fast car

It's a hard job

She drove too fast

They worked very hard

And also:

We need an outside light

We went outside

He's in the upstairs / downstairs study

He walked upstairs / downstairs

etc.

Finally, there are some adjectives which take on adverb-like

characteristics because, semantically, they imply the description of

a verb not a noun. In this list we find:

She's a hard worker (i.e., She works hard)

It's a fast road (i.e., You can drive fast on it)

They are frequent visitors (i.e., They visit

frequently)

I was a heavy smoker (i.e., I smoked heavily)

She's a light sleeper (i.e., She sleeps lightly)

They are occasional customers (i.e., They come

occasionally)

It was heavy rain (i.e., It rained heavily)

She's an attractive writer (i.e., She writes

attractively)

He's a beautiful singer (i.e., He sings

beautifully)

In all these cases, the usual meaning of the adjective does not

apply to the noun phrase, it applies to the way something is done so

the adjectives are really adverbials.

|

Adverbs in other languages |

All languages have ways to modify verbs and adjectives but how they do it and how recognisably different an adverb is from an adjective is very variable. No list of this kind is likely to get close to being exhaustive but here are some of the most obvious variations.

- suffixation

- English frequently forms adverbs by suffixation, usually with -ly,

as we saw, but there are other possibilities such as -wards.

Many, especially European, languages do the same kind of thing:

Romance languages, such as Spanish, Romanian, French and Italian, often add a suffix like -ment or -mente to the adjective form, from the Latin mentis [mind]. For example, the English adverb comfortably translates as:

cómodamente (Spanish), comodamente (Italian), confortablement (French), confortavelmente (Portuguese) and so on.

Scandinavian languages also use a suffix, -t, to make the adverb from the adjectives but, unfortunately, this sometimes makes it identical to a form of the adjective. For example, comfortable translates as:

bekvämt (Swedish), komfortabelt (Danish and Norwegian).

Japanese, too, has a range of suffixes to denote the change in word class, for example, the addition of /ku/ to the stem so we get:

haya (quick) and hayaku (quickly).

Hungarian works similarly with four possible suffixes.

Standard Arabic also has a suffix to denote an adverb (-an). Other varieties may differ.

Once learners with these backgrounds are alert to the parallel suffixation phenomenon, it is usually reasonably easy for them to form English adverbs naturally. - replacing the suffix

- In some languages, an adjective may be recognisable from its

suffix and in some of these, the suffix denoting an adjective is

removed and replaced by one denoting an adverb.

Greek, for example, replaces an inflexional suffix on an adjective to make it an adverb (usually by inserting -os or -a) so comfortable translates as:

άνετος (ahnetos)

but comfortably translates as

άνετα (ahneta).

In Russian also, and some other Slavic languages, including Latvian, adverbs can be formed by removing the adjectival suffixes from the adjective and replacing it with the adverb suffix (often -o in Russian).

In Korean, adverbs are often formed in a similar way, replacing endings rather than simply adding them.

In these languages, the normal inflexions that the adjectives take to agree with the nouns they modify are dropped when the adverb is formed. - using the adjective forms

- Dutch and German can use the same form as the adjective but make

it operate, invariably, as an adverb. Both the adjective

comfortable and the adverb comfortably then translate

simply as:

bequem (German) and comfortabel (Dutch and Afrikaans).

Turkish, Persian languages (except on words derived from Arabic), Bosnian, Croatian and Slovenian, too, make adjective forms stand equally well as adverbs.

Learners from these language backgrounds may not see the necessity to change the form of an adjective when it is converted into an adverb and that leads to error such as:

*He drove quick

*I sat comfortable - non-inflecting or isolating languages

- The classic example here is the Chinese languages in which a new word is inserted to denote the adverbial use of an attribute and distinguish it from the adjective.

| Related guides | |

| the word-class map | for links to guides to the other major word classes |

| adverbs essentials | for the essentials-only guide in the initial plus section of the site |

| adverbials | for more on adverbials which are not adverbs and distinctions between adjuncts, disjuncts and conjuncts |

| adverbial intensifiers | for a guide to intensifiers: amplifiers, emphasisers, downtoners and approximators (which are mostly adverbs) |

| multi-word verbs | for the guide which distinguishes an adverb from a preposition and much else |

| disjuncts | for a dedicated guide to adverbials acting to modify all the following text (also called sentence adverbials) |

| conjuncts | for a guide to how some adverbs function as cohesive cohesive devices, linking clauses and sentences |

| circumstances | for an alternative functional view of this area |

| fronting | for a discussion of how elements (often adverbs) can be moved out of their normal position for effect |

| prepositional phrases | for more on how these may act as adverbials |

| place adjuncts | which considers both adverbs and prepositional phrases of place only (i.e., position and direction) |

| time adjuncts | which considers the complicated and difficult area of adverbs and prepositional phrases of time |

| assertion and non-assertion | for more on these two concepts and how they apply to adverbs such as yet and already |

| negation | for much more in this area, including inversion after negative adverbs |

| cause and effect | for more on how some adverbs and other adverbials can link cause and effect |

| adjectives | for more on inflexional and periphrastic comparison and proleptic uses |

There is, of course, a test on this.

Reference:

Quirk, R, Greenbaum, S, Leech, G & Svartvik, J, 1972, A Grammar of

Contemporary English,

Harlow: Longman