Multi-word verbs (MWVs)

|

| breaking in |

Note: if this area is fully new to you, you may like to work through the essential guide to MWVs first (new tab).

If you are coming to this guide for the first time, you may want to work through it from top to bottom. It is quite a long guide with a number of sections so, if you are returning for a second or third look, here's an index of the sections.

At the end of each section, you can click on -top- to return to this menu, simply read on, scroll back or bookmark the page for another time.

|

Definitions and types of analyses |

What follows is one way of analysing

multi-word verbs.

There are other ways to do the analysis which are summarised here.

- One analysis recognises a word class called particles which are neither adverbs

nor prepositions (although they look like them). Particles are

function words, like conjunctions, prepositions etc., which have no

lexical meaning in themselves and need to combine with other words to

make any meaning. For example, on standing alone means

nothing but in a phrase such as get on the bus, it forms part

of a prepositional phrase which modifies how

we understand the verb get. And no, in this sense the

combination of get plus on is not a phrasal or

even a multi-word verb.

It really doesn't matter too much for teaching purposes whether you use the term 'particle', 'preposition' or 'adverb'. Here, we'll use the adverb-preposition distinction, reserving the term 'particle' for either of them. We will not follow this sort of analysis because, for teaching purposes, it is too vague a definition and disguises many differences in the ordering of the constituents of a clause which are important as well as leaving the nature of adverbs, adverb particles and prepositions unclear.

It also leads to a situation in which virtually any adverb following a verb may be classed as a phrasal verb and that, in its turn, leads to an unacceptable learning load. It is perfectly possible to understand, e.g.:

She got on the bus

by analogy with

She put it on the table

because in both cases, the particle on is acting as a preposition of movement to a place above ground level. And, naturally enough, get off carries the opposite meaning. - In other analyses of multi-word verbs, you will discover that all of

them are lumped together as 'phrasal verbs'. This is not the

approach taken here but it makes some kind of sense – multi-word

verbs are, by definition, phrases, so why not call them by that name?

Analyses which take this line may distinguish between particle verbs,

prepositional verbs and particle-prepositional verbs. Roughly

speaking, these categories are similar to the ones used here.

We will not be using this analysis either because the distinction between an adverb particle and a prepositional particle is necessary for teaching purposes in order that the major patterns can be discerned and taught independently. - A now slightly unfashionable analysis is to call all verb +

particle structures phrasal verbs (whether the particle is an adverb

or a preposition) and then to divide them into four types.

This is the approach taken in many course books and can be helpful

in the classroom but we will not be using this analysis here because

it overcomplicates the issues. The four types, incidentally,

are:

- Type 1: intransitive phrasal verbs consisting of a verb plus an adverb particle such as Come on!

- Type 2: transitive separable phrasal verbs consisting of a verb + a preposition or adverb such as Put it away!

- Type 3: transitive non-separable phrasal verbs consisting of verb + a preposition such as Look after the children!

- Type 4: verbs containing two or more particles, the first an adverb and the second a preposition such as Stick up for him

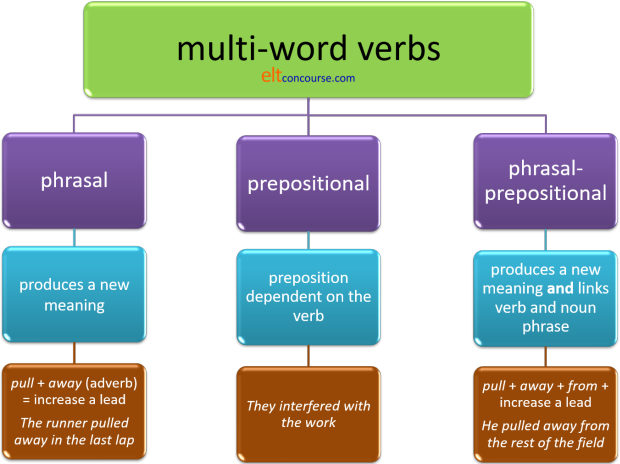

There are sound reasons for using any of these three ways of classifying and analysing multi-word verbs and you should use the one that makes the most sense to you. However, this analysis will use three categories of multi-word verbs and discuss them individually. These categories are:

- Phrasal verbs which contain a verb plus an adverb such as

cut up. In this analysis, these verbs are separable, if

they are transitive, so

one can have

I cut it up

or

I cut up the tree

or

I cut the tree up

but not

I cut up it - Prepositional verbs which contain a verb plus a dependent

preposition such as rely on and which are not separable,

the object always following the preposition, so one can have

I relied on her help

and

I relied on it

but not

*I relied her help on

or

*I relied it on - Phrasal-prepositional verbs which contain a verb followed by an

adverb and a preposition are a subset of prepositional verbs.

These are also inseparable so we can have:

He lived up to his name

but not

*He lived his name up to

or

*He lived up his name to

This analysis leaves an indeterminate class of multi-word

verbs: those which are inseparable but which are variably opaque in

meaning and often quite idiomatic such as care for, look after

or go without. In this category we can have:

He cared for his patients

or

He cared for them

but not

*He cared his patients for

or

*He cared them for.

In what follows this, we analyse these verbs in the same way that it we

analyse prepositional verbs (category ii. above) because they follow the

same patterns in terms of grammatical structure (i.e., they are not

separable and the object

follows the particle). For teaching purposes, therefore, they can

be dealt with in the same way and should not form a separate

category (usually referred to as intransitive phrasal verbs)

because that simply muddies the water and overloads learners.

The argument here is that they are simply another set of prepositional

verbs which often have slightly figurative or metaphorical uses of

prepositions. When the particle is an adverb, combining with the

verb to form a distinctly new meaning, they will be referred to as

phrasal verbs.

Here's a summary of the four main ways of analysing this area of English. You will encounter all of them at some time, probably, so need to decide which to follow. Mixing them up is a recipe for confusion. What follows adheres to Analysis #4.

|

Distinguishing between adverb particles and prepositions |

This is the first thing we need to do because we can't begin to

analyse multi-word verbs until the distinction between a particle as a

preposition and a particle as an adverb is clear.

The immediate problem is that nearly all the words can function as both

adverbs and prepositions, depending on the grammar.

There's a test. To see it work, consider this sentence:

John is standing in for me

Prepositions in black, adverbs in red in what follows.

- Prepositions

- take a complement (not, in this analysis, an object although that is a

legitimate description).

The word for is a preposition because it has a complement, me, which can be altered without changing the sense of the verb. So, we can have for Mary, for the moment, for the time being, for the boss of the company and so on. - Adverbs

- do not take a complement. In the clause above,

in

is an adverb, not a preposition.

If we give it a complement such as the house, the water, the garden etc., it will be a preposition and the meaning will alter.

For example, the sentence

He is standing in the garden

clearly contains the preposition in. It is not a phrasal verb or even a multi-word verb.

If you change the particle when it really is an adverb, however, the verb meaning changes. So we can have

He is standing up for her

meaning support or back someone. We can also use for as an adverb as in

I won't stand for his behaviour

and that is a different verb with a completely different meaning (tolerate).

|

Please be careful |

The title of this section includes the term 'adverb particles' rather

than 'adverbs' for a

good reason.

We should be careful to distinguish between an adverb particle as part

of a phrasal verb and a one-word adverb functioning to modify the verb.

For example, the clause:

He looked me up

contains the adverb particle up and is a phrasal verb

because changing the particle to, say, down, away, in etc.

creates nonsense. In fact, the verb alone is intransitive so:

He looked

is meaningless unless what he looked at or for is clear.

When it is a phrasal verb, as in the first example, it is transitive and

means either visited or found in a reference text.

It is not possible to omit the particle and

retain the verb's meaning.

We can, of course, have

He looked me over suspiciously

and, by changing the adverb particle, we have changed the sense of the

verb.

However, in the clause:

He rang me back

the situation is not so clear cut because a number of other one-word

adverbs could be inserted instead of back, without altering the

meaning of the verb ring at all so we can have

He rang me soon

He rang me again

He rang me yesterday

He rang me frequently

etc.

We can also have:

He rang me

with no adverb and an unaltered sense of the verb.

With a phrasal verb proper, omitting the particle is usually not

possible so, for example:

He looked up the word in a dictionary

cannot be rendered as

*He looked the word in a dictionary

because it is the combination of the verb and the adverb which

supplies the meaning. The adverb up does not modify

the verb, in other words, it contributes to the meaning of the whole

phrase. That is why it is called a phrasal verb.

So, by this analysis, the phrase ring back (or call back)

does not constitute a phrasal verb as such although it may be treated

that way in many course books, internet-derived lists and classrooms.

Assuming always that single-word adverbs must be parts of phrasal verbs

is unhelpful because it adds an additional learning load which is simply

not necessary. You do not need to learn

call back

text back

ring back

write back

talk back

shout back

email back

phone back

and so on as phrasal verbs once the meaning of the adverb back has been

learned. They aren't phrasal verbs at all because

the sense of the verb is being modified but not fundamentally altered by the adverb.

In all cases, the particle can be omitted without creating nonsense.

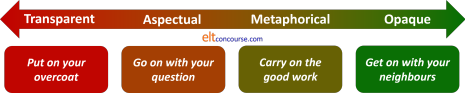

Combinations which are transparent in meaning of a verb with an

adverb are sometimes referred to as transparent phrasal verbs

and there is some value in doing so as the combinations often act

grammatically in the same way as phrasal verbs proper. For

example, they are variably transitive and almost always separable.

However, to consider all examples of transparent meaning combinations of

verbs and adverbs as phrasal verbs adds an enormous and wholly

unnecessary learning load.

If learners understand the meaning of the verb and the meaning of the

adverb particle, there is no need to burden them with the need to learn

the combination as a language chunk.

For example:

I took my pen out

merely requires one to understand the prototypical meaning of the adverb

out (from the inside to the outside). Suggesting that take out is a

phrasal verb in this case is unnecessary.

Even if we accept that transparent phrasal verbs are phrasal verbs at

all, rather than just verbs modified by adverbs, there is no need to

mystify them and certainly no need to require learners to learn each

one separately.

|

Modification vs. integration |

So, to summarise, we need to distinguish between:

- Adverb modification:

In which the adverb serves to say how the speaker / writer perceives the verb operating and that includes, for example:

He came back

She went there

The car drove past

She came quickly over the road

They went happily to the beach

The car drove noisily up the hill

etc.

In these cases, the adverb is mobile so we allow, for example:

The car drove up the hill noisily

She quickly came over the road

Back he came

and so on.

In other words, the constituents of the clause are:

Subject noun phrase (he, she, the car etc.)

Verb phrase (came, went, drove etc.)

Adverbial or adverb phrase (back, there, past, quickly etc.)

and we can go on adding adverbial phrases of one kind or another virtually indefinitely. - Adverb integration

In which the adverb functions as part of a verb's meaning and that includes, for example:

The car wore out

They talked her round

She broke it down to make it simple

I get up at 9

He came to in hospital

The boss put off her meeting

In these cases, when the verb is transitive, the adverb may be separated from the verb by the object so we allow, e.g.:

The boss put her meeting off

The boss put it off

and

The boss put off her meeting

but we do not allow:

*The boss put off it

because a defining characteristic of separable phrasal verbs is that any object pronoun must come between the verb and the adverb particle.

In other words, the constituents of the clause are:

Subject noun phrase (the car, they, she etc.)

Verb phrase (wore out, talked round, broke down, get up etc.)

Object noun phrase (it, her meeting)

and we can go on adding adverbial phrases of one kind or another virtually indefinitely to arrive at, for example:

The boss put off her meeting yesterday afternoon to her great disappointment because he thought ...

To see if you have understood the distinction between adverbs and

prepositions, analyse the following

examples, identifying the bits which are adverbs and which

are prepositions.

Then click on the

![]() to reveal some comments.

to reveal some comments.

| He pulled off the trick |

Here,

off is an adverb.

If you change it, you change the meaning of the verb: *He pulled through the trick *He pulled up the trick etc. By our definition, this is a transitive phrasal verb with the object the trick and it means succeed in doing something. The prototypical meaning of the verb pull (something like drag or tow) does not include the sense of success, of course so the phrasal verb is quite opaque in meaning. |

| He opened up to her about what was

worrying him |

Here we have two bits to consider,

up and to.

Changing up will alter the meaning of the verb or make it nonsense. The word to takes a complement, her, and the whole phrase can be substituted or even omitted. So we can have, e.g.: He opened up to the group about what was worrying him or He opened up with me because I'm his friend in which we have changed the preposition but kept the adverb intact. We can also just say: He finally opened up retaining the meaning of open up. So, in this example, up is an adverb and to is a preposition. Phrasal verbs are often followed by prepositional phrases and it is important to identify where the verb stops and the prepositional phrase begins. In this case the verb open has retained its prototypical meaning of expose or make unclosed but it is used metaphorically when it combines with the adverb up. The verb can be used with a prepositional phrase as in, e.g.: The house is open to the public |

| They moved on to the next item on the

agenda |

Here we also have two bits to consider,

on and

to.

You can't change on without changing the meaning, if only slightly: They moved along They moved away but you can change the prepositional phrase with to to something else such as: They moved on by considering the last item etc. So, on is an adverb and to is a preposition. (Incidentally, the confusion between onto (a single-word preposition) and on to (an adverb particle and a preposition) is solved by this analysis. The words can only be combined when they are both prepositional.) |

| She's has difficulty getting up

these days |

Here there's only

up to

consider.

Change it and the meaning alters dramatically, e.g.: She has difficulty getting about these days. So, up is an adverb and the verb itself is an intransitive phrasal verb. The meaning is, however, at least semi-transparent if one understands the usual meaning of the adverb up. The problem with the verb get is a separate issue because it is notoriously polysemous, having a range of connected but distinct meanings. Here, it carries the very common meaning of move one's position so it also appears in: Get on Get out (both verb + adverb) and in Get off the bus Get away from the fire (both verb + prepositional phrase) etc. |

| They complained about the service |

Here, again, we only have one item,

about.

It's a preposition because it takes the complement the service, and the whole prepositional phrase is the complement of the verb complain. The verb complain + about is a prepositional, not phrasal, verb. The service is the not object of the verb, it is the complement or object of the preposition about because complain is intransitive. When used with no complement, the preposition is dropped, so we get, for example: I complained loudly We can change the preposition but the meaning of complain is unaltered: They complained to the manager They complained at reception and we can drop the prepositional phrase altogether and have just: She complained To repeat a little, the preposition may change without altering the meaning of the verb: She complained of a pain in her back This, therefore, is a verb with a dependent preposition or, in this analysis, a prepositional verb, not a phrasal verb. |

|

Moving on ... |

In this analysis, there are 3 sorts of multi-word verbs: phrasal verbs, prepositional verbs and phrasal-prepositional verbs. Before we investigate the difference, we need to recognise a true multi-word verb. Consider these two sentences and identify the true MWV. Click here when you've done that.

- He turned down the lane

- He turned down the offer

In Sentence 1, we can change down without changing the

meaning of the verb:

He turned left at the fork

He turned sharp

right at the crossroads

He turned by the church etc.

In Sentence 2, changing down changes the meaning of the

verb:

He turned over the offer

He turned to the offer

He turned up

the offer etc.

Sentence 1 contains a verb followed by a

prepositional phrase.

Sentence

2 contains a true multi-word verb.

|

Nine other tests for MWVs |

There are other tests, none decisive on its own:

|

Does replacing the particle change the meaning of the verb? |

This is actually a test not for any multi-word verb but for

phrasal verbs in particular. There's a good deal more about

how to distinguish between a prepositional verb and a phrasal verb

below. For now, this example will do:

If we replace the particle in a sentence such as:

She ran back

and change it to

She ran ahead

or

She ran about

it is clear that the meaning of the verb is unchanged. It

means go quickly on foot in all three sentences.

However, if we try the same trick with a sentence such as:

She turned up later

and change it to

She turned away later

or

She turned aside later

etc.

it is clear that in the first sentence the verb, turn up,

means arrive but in the others it means something much more

literal (change attitude). The verb's meaning contains

the sense of the particle in the first sentence but not in the other

sentences.

So, the verb turn up passes this test for a multi-word

verb. It is, in fact, and intransitive phrasal verb. The

expressions turn away and turn aside are not

multi-word verbs; they are simply verbs modified by a following

one-word adverb phrase.

Incidentally, Henry Sweet (1845-1912) referred to verbs whose parts combined to make a new and distinct meaning (such as turn up in our example) as group verbs because the meaning depended on the grouping rather than the individual constituents. That definition has rather fallen out of fashion so we won't be using it here. It remains, however, a useful distinction to draw.

|

Can you make a passive? |

You can't say

*The lane was turned down

but you can say

The

offer was turned down

You often cannot make a passive with prepositional phrases but you can with

many transitive phrasal verbs.

Here's another example:

We can have either:

She looked up the word

and

The word was looked up

because the verb is look up.

However, it is often much more questionable when we try to make a

passive form with a verb plus a prepositional phrase so, while:

She looked up the chimney

is the active form, many would not accept:

?The chimney was looked up

This is not, however, a particularly firm rule because some

prepositional phrases can be manipulated in this way and we might

allow, e.g.:

The house was driven past

although that is an unusual form to encounter.

|

Can you stress the particle or use a weak form? |

Compare:

He came to the meeting

and

He came to after a while

In the first, to is often

pronounced as /tə/, in the second, the particle is usually

pronounced in its full form /tuː/.

We can and often do pronounce adverb particles in their full form.

Compare, too:

He got on the bus

They got on well together

and you'll hear that in the first case,

on is not

stressed and in the second, it is. This is because in the

first example, on is just a preposition of movement to

a higher place but in the second, it is an adverb which affects

the meaning of get and is part of an intransitive

phrasal verb.

|

Can you move the complement phrase around? |

You can say

Down the lane he turned

but not

*Down the offer he turned

Moving a prepositional phrase is possible for effect

(marking it for special emphasis, usually) but moving an adverb

particle usually results in nonsense.

We can also allow, e.g.:

Over the hills they marched

but not:

*Over the figures he went.

A common device in English to move a phrase for a special or

marked meaning is to create a cleft sentence and that will result

in:

It was down the lane that he turned

but that is not an available option with a phrasal verb because

it results in the ungrammatical:

*It was down the offer that he turned.

We can also have, for example:

About her new job, she spoke for hours

and:

In French she spoke more slowly

but not:

*Over the idea they spoke

and this reveals that talk about and talk in

are verbs followed by prepositional phrases but talk over

is a true phrasal verb in which the verb and the particle combine to

make a new meaning (discuss).

|

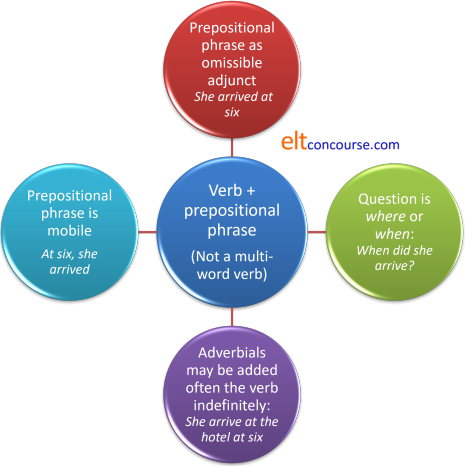

Does the question ask what or who or where, how, the subject or when? |

There are really two questions here:

- If it's answering what or who it's a true

MWV. For example:

What did she knock down → She knocked down the old shed

Who did she cut off? → She cut off the caller

What did she look up? → She looked up the word 'silage'

Who looked up the words? → She did

are examples of a true MWVs. - Prepositional phrases refer to where, how, the subject and

when:

Where did he arrive? → He arrived at the hotel

When did he arrive? → He arrived at 6 o'clock

Where did she look? → Up the chimney

When did they go? → After the end of the play

What did she talk about? → Her new job

What language did speak? → She spoke in French

so, arrive at, look up, talk about, talk in and go after in these sentences are not MWVs but verbs followed by prepositional phrases which can be replaced by, e.g.:

at 6 o'clock

in the garden

by the early afternoon

etc.

Functionally, items which tell us where or when are acting

as circumstances but those which tell us who or

what are acting as participants in the clause.

Circumstances can be omitted, participants cannot.

|

What exactly is the question? |

If we ask the question which elicits:

down the lane

as the answer, it is clear we are dealing with a prepositional

phrase because the question will be

Where did she turn?

On the other hand, we cannot discover a question which will

evince:

down the offer

because

What did she turn?

does not work.

We can, however, ask:

What did she turn down?

and that

will evince the

answer:

the offer.

If the question contains both the verb and its associated

particle, we are dealing with a single meaning so it's a

multi-word

verb.

|

Can you insert an adverb phrase or adverbial? |

You can say

He turned immediately down the lane

but not

*He turned immediately down the offer

Inserting an adverb before a prepositional phrase is

commonplace. Doing it to an adverb particle usually results in

non- or questionable English. You can, of course, put an adverb after the

object of a phrasal verb as in

He turned down the offer immediately

and you can put one before the verb as in

He immediately turned down the offer

If you cannot naturally split the particle from the verb with an

adverb, you are dealing with a multi-word verb.

(There are a very limited number of adverbs which can modify the

adverb particle of a phrasal verb so we can allow, for example:

She hit right on the solution

The anaesthetic has worn well off

but this rare.)

|

Can we discover a one-word alternative? |

This is a test which cannot always be applied because for

some phrasal verbs no single-word alternative exists. For

most, however, there is a single verb which can replace both the

verb and its adverb particle and if there is, we are probably dealing

with a phrasal verb. For example, with:

She

turned into the driveway

it is not possible to find a one-word alternative to the

underlined section of the sentence. We can replace the

first part with, e.g., drove, or even manoeuvred

and we can replace the second part with something like in

or along or at (although the sense of

direction changes a little). We cannot, however, replace

both parts at once with a single word.

With a sentence such as:

She turned

down the offer

it is possible to replace the underlined section with a single

verb so we could have:

She refused the offer

She declined the offer

She rejected the offer

with very similar meanings.

Above and elsewhere in this guide, we

define into as a preposition because it is always

followed by a complement (or object if you prefer). This

means, in effect that combinations such as turn, change,

make etc. with into are not phrasal verbs at all

but a verb plus a prepositional phrase with the preposition

indicating a change of state rather than a change of position.

In that analysis,

turn into is a pseudo-copular verb

which indicates a change of state and is in the same category as

grow, become, get, end up and more.

This test is not always definitive and it is true that some verb

plus preposition combinations can be replaced by a single word.

For example, the verb

turn into can be replaced with a single verb:

She

turned

into a dictator = She became a dictator

but it does not make it a phrasal verb.

|

What actually is the verb? |

This is related to Test 7 (What is the question) and concerns how we analyse

meanings embedded in the

clause.

The question to ask is

Is the structure

verb +

prepositional phrase

or

verb + direct object?

The test is to insert a complement (or object, if you prefer).

Prepositions take complements (or objects), adverbs do not. So,

for example:

She turned down the road

is a case of a preposition,

down, taking the complement

(or object), the road, to form a prepositional phrase

and we could also have

She turned into the driveway

She turned round the corner

Here the structure is:

verb + prepositional phrase.

So the verb is simply turn.

However, when we consider:

She turned down my idea

we have down functioning as an adverb because the

structure is:

phrasal verb + direct object

and in this case, the verb is not

turn, it is turn

down as can immediately be seen if one replaces the adverb

with another:

She turned over my

idea in her mind

where the adverb is combining with the verb to make new meanings

(consider).

(The verb turn is often combined with the preposition,

into, to make a pseudo-copular verb as in, for example:

She turned into a princess

The combinations of

turn + into along with change

and make + into are not phrasal verbs because

the preposition into happens to have one meaning (among

others) of indicating a change of state. See below for

more on the meanings of into.)

|

A checklist and a task (if you like) |

If you would like to try the questions out for yourself when considering how to analyse an item, here's the checklist. If you would like it as a PDF document, click here.

|

Here are four clauses to analyse using the check-list questions:

Bear in mind that not all the tests will work perfectly with all

examples. It is a cumulative effect. |

- They

sorted out the house

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

Yes, replacing the particle changes the meaning of the verb.

They sorted through the house

has a different meaning of something like looked through rather than organised.

Almost any other adverb particle will create nonsense. - Can you make a passive?

Yes, we can make a passive as in:

The house was sorted out - Can you stress the particle or use a weak form?

Yes, the stress can be placed on out and the verb will take equal stress usually. - Can you move the phrase around?

No, we cannot move the phrase around and allow:

*Out the house they sorted

There is also no way that we can produce a cleft sentence such as:

*It was out that they sorted the house.

so the verb fails this test. - What is the question asking?

- Does the question ask what or who?

Yes, it asks

What did they sort out?

and the answer is the house.

Equally, we can allow:

Who sorted the house out?

and that will be answered by:

They did. - Does the question ask where or when?

No. We cannot make the question as:

*When did they sort?

or

*Where did they sort?

because both are unanswerable. The verb fails this test.

- Does the question ask what or who?

- Is the particle part of the question?

Yes, the particle is part of the question which is:

What did they sort out?

not

*What did they sort? - Can you insert an adverb?

No, we cannot easily insert an adverb between the verb and its particle so:

*They sorted eventually out the house

is not acceptable and the verb fails this test. - Can we discover a one-word alternative?

Yes, there is a one-word alternative. The verb sort out can be replaced with organised or tidied. - What actually is the verb?

Here we need to think about meaning.

Intuitively, we can say that the verb is sort, of course, but a little thought reveals that the meaning is encapsulated in the phrase sort out which has a rather different and extended meaning. There is a difference, albeit small, between:

They sorted the books

and

They sorted out the books

because the first refers to setting things in a particular classified order and the second to tidying.

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

- She

drove on to the supermarket

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

Yes, replacing the particle changes the meaning of the verb.

She drove off to the supermarket

is a different meaning because it implies she started not continued the journey. - Can you make a passive?

No, we cannot make a passive because the verb is intransitive. The verb doesn't fail this test because the test simply cannot be applied to a verb with no object. - Can you stress the particle or use a weak form?

Yes, the stress can fall on on quite naturally. - Can you move the phrase around?

Just possibly, although most people will suspicious of:

?On to the supermarket she drove

and, although it is an unusual form, we can move the prepositional adverbial phrase and allow, grammatically, at least:

To the supermarket, she drove on

We can also not allow a cleft sentence so, for example:

*It was on that she drove

is not permitted. - What is the question asking?

- Does the question ask what or who?

Yes, it asks:

What did she do?

and the answer is drove on.

The alternative question could be:

Who drove on?

and that will evince:

She did. - Does the question ask where or when?

Not really. The question could be:

Where did she drive?

but that will not get the answer:

*On.

And the question:

When did she drive?

does not allow the answer

*On

at all.

- Does the question ask what or who?

- Is the particle part of the question?

Yes, the particle is part of the question which asks:

Where did she drive on to?

not

Where did she drive?

and the answer is the supermarket. - Can you insert an adverb?

No, we cannot easily insert an adverb between the verb and its particle so:

*She drove eventually on

is not acceptable. - Can we discover a one-word alternative?

It is not easy to find a one-word alternative although we can say:

She continued

She motored

She drove

without much change in meaning. - What actually is the verb?

Here again we need to think about meaning.

Intuitively, we can say that the verb is drive, of course, but a little thought reveals that the meaning is encapsulated in the phrase drive on which has a rather different and extended meaning. There is a difference, albeit a small one, between:

She drove to the supermarket

and

She drove on to the supermarket.

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

- Mary

walked around the village for a while

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

No, replacing the particle does not change the meaning of the verb, because:

Mary walked to the village

Mary walked past the village

Mary walked towards the village

still mean that the verb is go on foot. Changing the preposition has no effect on the meaning of the verb. - Can you make a passive?

No, we cannot make a passive and most people will not accept:

*The village was walked around for a while by Mary - Can you stress the particle or use a weak form?

No, the stress would not usually fall on around. unless we have a good reason to emphasise the preposition (by, for example, contrasting it with to). - Can you move the phrase around?

Yes. We can have:

Around the village Mary walked for a while

or

For a while Mary walked around the village

and we can also produce a cleft sentence to get:

It was around the village that Mary walked. - What is the question asking?

- Does the question ask what or who?

No. - Does the question ask where or when?

Yes, it asks

Where did Mary walk

or

How long did Mary walk?

and the answers are

around the village

and

for a while.

- Does the question ask what or who?

- Is the particle part of the question?

No, the particle is not part of the question. The question would usually be:

Where did Mary walk?

not

*Where did Mary walk around? - Can you insert an adverb?

Yes. We can insert any number of adverbs:

Mary walked happily around the village for a while

Mary walked around the village lazily for a while

Mary walked curiously around the village for a while

and so on. - Can we discover a one-word alternative?

Not easily. We can replace the verb and have:

Mary sauntered / strolled / ran / galloped around the village

and we can replace the preposition and have:

Mary walked all over / into / to / past the village for a while

but there is no one-word replacement for walk around. - What actually is the verb?

Here again we need to think about meaning and when we do, it's clear that the only action being described is walk. Everything else in the clause is simply telling us where and when.

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

- Peter abstained

from the vote

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

Yes, replacing the particle actually makes an ungrammatical clause because the only preposition which is possible is from. If we replace it, we get nonsense as in:

*Peter abstained to the vote. - Can you make a passive?

No, we cannot usually make a sensible passive with this sort of combination. Most would not accept, therefore:

*The vote was abstained from by Peter

This test is not definitive with many verbs of this nature, however because we may, for example, accept:

?My help was relied on

although it somewhat unusual and clumsy. - Can you stress the particle or use a weak form?

No, so this test is failed. We would not normally stress the preposition from in our example sentence and the preposition (for that is what it is) would take its weakened form and be pronounced as /frəm/ rather than /frɒm/. - Can you move the phrase around?

Just possibly, although most people will suspicious of:

?From the vote Peter abstained

and with other verbs like this, although it is an unusual way to phrase the clause, we can move the prepositional adverbial phrase and allow, grammatically, at least:

?On my help, everyone relied

We can also allow a cleft sentence so, for example:

It was on my help that everyone relied

is permitted.

This doesn't always work, however, because few would accept:

?It was from the vote that Peter abstained. - What is the question asking?

- Does the question ask what or who?

Yes, it asks:

What did he abstain from?

and the answer is the vote.

The alternative question could be:

Who abstained from the vote?

and that will evince:

Peter did. - Does the question ask where or when?

No. The question could be:

Where did Peter abstain?

but that will not get the answer:

*The vote.

And the question:

When did Peter abstain?

does not allow the answer:

*The vote

at all.

- Does the question ask what or who?

- Is the particle part of the question?

Yes, the particle is part of the question which asks:

What did Peter abstain from?

and the answer is

the vote.

But we cannot ask

What did Peter abstain? - Can you insert an adverb?

Perilously. We could, perhaps accept:

?Peter abstained reluctantly from the vote

but we would probably prefer:

Peter abstained from the vote reluctantly. - Can we discover a one-word alternative?

No. There is no one-word equivalent of abstain from. - What actually is the verb?

Here again we need to think about meaning.

Intuitively, we can say that the verb is abstain, of course, but we saw above that the question will contain the preposition from. The preposition actually adds nothing to the meaning of the verb at all (unlike examples A and B) but the collocation is very strong. In response, for example, unless the object is known and assumed, a statement such as

Peter abstained

will commonly evince

From what?

as a response.

- Does replacing the particle change the meaning

of the verb?

Conclusions:

- sort out is a multi-word verb. It is, in fact, a separable, transitive phrasal verb.

- drive on is also a multi-word verb. It is, in fact an intransitive (and, therefore, inseparable) phrasal verb.

- around the village and for a while are both adverbial adjuncts. In this case, they are prepositional phrases which do not affect the meaning of the verb. There is no multi-word verb walk around. That is just a verb post-modified by an adverbial.

- abstain from meets some of the

tests for a multi-word verb but not all of them so it seems to

occupy a rather uncomfortable zone between a true multi-word

verb such as sort out and verb plus a prepositional phrase

adverbial such as walk around XXX.

It is, in fact, a form of multi-word verb but it is not a phrasal verb. In this guide it will be analysed as a prepositional verb but others will call it a verb with a dependent preposition.

|

Website warningThere are rather too many websites out here that cannot distinguish between

a real MWV and a simple verb followed by a prepositional phrase or a

modifying adverb. |

For

example, one site describes walk into a trap as a phrasal verb.

Another site describes run after the bus as a phrasal verb.

These are not examples of phrasal verbs. They aren't even prepositional verbs. They are simply

the verbs walk and run followed by a prepositional phrase (into a

trap, after the bus). This may be a slightly metaphorical use of walk

but that's another matter altogether.

Many particles can be either prepositions or adverbs and therein

lies the source of much confusion.

We can change the prepositions without affecting the basic meaning of

the verb in any way. For example, we can have:

walk

along the path

walk around the town

walk into a room

walk over a hill

run behind the bus

run in front of the bus

run

alongside the bus

run past the bus

etc.

Other examples from a website for learners which claims to explain 56

common phrasal verbs (some of which are not at all common and some of

which are not phrasal verbs) are

fall down

go ahead

and

log into

The first and second of those are simply verbs

being modified by adverbs and we can just as easily have:

drop down

climb down

walk down

stroll down

run ahead

drive ahead

throw ahead

look ahead

and so on where the adverb is not altering the meaning of the verb.

Even the expression:

Go ahead!

meaning

Please continue

is simply a slightly figurative use of

the adverb which needs no special treatment once the meaning of the

adverb ahead has been grasped.

The third example, log into, is even worse because it is just a

verb followed by a preposition which needs a complement such as the

site. Even when we make the preposition into an adverb and

just have log in or log on, it remains a simple verb plus adverb

combination so we can also have:

log out

or

log off

without changing the

meaning of the rather unusual verb. In fact, the word into is a preposition

and is so defined in dictionaries.

None is a phrasal verb so the site's admonition to learners to remember

these expressions as if they were phrasal verbs is unhelpful and

confusing, not to say time wasting, careless and borderline

irresponsible.

By the same token, something like

John ran in

is not a phrasal verb, it is simply a verb modified by an adverb of

place so we could equally well have:

John ran out

John ran away

John ran by

all with simple adverb modifiers which do not affect the meaning of

run at all. We can also, incidentally, have:

John ran yesterday

and

John ran often

or just

John ran

However, when we encounter

The police ran in John

or

The police ran John in

it is clear that the meaning of run has been radically altered

(to mean arrest and take into custody) by the adverb particle

and we are, therefore, dealing with a phrasal verb because changing

in or removing the particle will change the meaning of run.

We cannot say

The police ran over John

and retain the same meaning of run.

We can apply our test 9 here. The question is,

can we find a one-word equivalent for the meaning?

To some extent we can so, for example:

John ran away

could be replaced by

John fled

but the sense of run is lost.

Replacing

John ran out

with a single-word alternative is not possible, however and we need to

resort to something like

John left, running

However, with:

The police ran John in

we can replace the verb and produce

The police arrested John

and retain the meaning (but not the style).

|

More misleading errors |

Don't believe everything you read.

Here are some other bits of misinformation from around the web. You may encounter phrases such as these analysed, if that's the word, as phrasal verbs:

- I tried to do the crossword but got

stuck

No. That's the verb get used as a copular verb to connect the subject to the adjective stuck. Compare, e.g.:

We got lost.

They got angry. - I'm trying to get

rid of this cold

No. That's similar with the verb get again meaning become and the adjective rid. The adjective is derived from the verb rid, incidentally because it was originally an irregular verb which did not change its form when used as a past participle. Compare, e.g.:

We have got free of debt.

They are rid of visitors. - He is about to phone her now

No. This is the marginal modal auxiliary verb be about which is followed by the to-infinitive. Compare, e.g.:

She means to see the doctor. - She got in touch with me

No. This is the verb get meaning become, move or achieve followed by a prepositional phrase. Compare, e.g.:

She got in contact with me.

She got in the bath.

In this case, too, we can replace the preposition in with into (which is always prepositional and not adverbial).

The use of the verb get in this case is metaphorical but metaphor is not a marker of a multi-word verb. - The party takes place

on Thursday

No. This is a slightly tricky idiom but the word place is a noun, not an adverb or preposition. Compare, e.g.:

Let's swap places.

The investigation is in place.

etc.

They aren't phrasal or prepositional verbs, of course. Only one, the fourth, even contains a prepositional phrase and none contains an adverb.

|

The key |

You may be thinking that this is all very complicated and

difficult, but there is a key. It is to analyse the

expressions carefully and decide if we are dealing with a

combination of verb plus particle which represents a single verbal

process or whether we are dealing with a verb modified by an adjunct

(either an adverb or a prepositional phrase).

To labour the point, because it is an important one, here are some

more examples:

- She ran up a huge bill

Here we are dealing with a single verbal process expressing her behaviour. We cannot remove the particle and we cannot remove the object because the verb is stubbornly transitive. It is a true transitive multi-word verb and, more specifically, a phrasal verb.

It is analysed as:Subject Verb phrase Object She ran up a huge bill - She ran up the hill

Here we are dealing with a verb + a prepositional phrase which acts as an adjunct, modifying how we see the verb run. We can remove the adjunct and leave a sensible and well-formed clause. We can also replace it with a huge range of other adjuncts, prepositional and adverbial to produce:

She ran down the road

She ran frantically

She ran home

She ran to her mother

etc.

It may be analysed as:Subject Verb phrase Adverbial She ran up the hill - The butterfly sucks up the nectar

from the flowers

This is more difficult because, on the face of things we have an adjunct but a moment's thought reveals that the process is the verb suck up and the nectar is the object of the verb. We do have an adjunct in the phrase from the flowers, of course. This is a phrasal verb, albeit one whose meaning is reasonably transparent because of the simple meaning of the adverb up.

It may be analysed as:

In this case, it is difficult to discover a one-word equivalent for the phrasal verb, incidentally.Subject Verb phrase Object The butterfly sucks up the nectar from the flowers - I slept in this morning

In this case, it is tempting to see sleep in as an intransitive multi-word verb. However, it is actually a verb plus an adverb adjunct, in. It could be replaced with a small range of other adverbs such as deeply, late or soundly which collocate with sleep but the verb itself will remain untouched in terms of basic meaning.

It may be analysed as:Subject Verb phrase Adverb Adverbial I slept in this morning - They set up the new system

Here, we just need to look for the process and it is clear that it is the phrasal verb set up which means something like establish (or, in other environments, build or erect). The question would be:

What did they set up?

not

What did they set?

It may be analysed as:Subject Verb phrase Object They set up a new system - They dropped out of the team

This is a more complicated case because we have both systems operating together.

Firstly, we have a phrasal verb, drop out, meaning something like abandon or stop participating in. It is a true phrasal verb because it will remain in part of any question and it is possible to find a one-word equivalent. It passes the nine tests we set up above.

We can compare it to, for example:

She dropped it out of the window

which is the stand-alone verb drop plus a prepositional phrase adverbial adjunct out of the window. The fact that the preposition consists of two words (out of) should not disturb us.

Secondly, we have the prepositional phrase, of the team, which is an adjunct modifying the verb drop out. The verb collocates very strongly with the preposition of so we can classify the whole multi-word unit as constituting a phrasal-prepositional verb and those are analysed below.

It may be analysed as:Subject Verb phrase Adverbial They dropped out of the team - They talked about their

experiences

They talked over the problem

Here, we have two examples of different kinds on verb uses

The clauses can be analysed like this:

and it's clear that we can insert other prepositional phrases with altering the meaning of the verb so we could also have:Subject Verb phrase Adverbial They talked about their experiences

They talked in French

They talked of their ambitions

and so on.

However, with the second example, we have encountered a phrasal verb because the verb talk and the adverb over have combined to form a new meaning. The analysis is, therefore:Subject Verb phrase Object They talked over the problem

|

Inflation |

Poor analysis often results in inflating the category of multi-word verbs to the point where extremely long lists can be produced which contain some legitimate examples but many others which do not belong. This means that learners become intimidated and teachers become overloaded by the need (so it is perceived) to teach and learn an enormous number of language chunks which are much more easily handled by taking a more analytic approach and breaking things down logically.

One well-known website intended to help learners of English lists 170 combinations which, the poor students are told, are the minimum they need to learn for successful communication. A brief analysis of the list shows, in fact, that only around half are really multi-word verbs at all and the rest are mostly combinations of verbs and one-word adverbs which do not affect the verb's meaning. Some are prepositions, too, and one or two, such as look forward to are idiomatic expressions which are phrases but not phrasal verbs.

You may think this is just a minor problem because lots of people can't do very good language analysis and that's true but bad analysis like this has implications for learners which are not good.

- It means that learners are misled about what constitutes a

learnable phrase and what constitutes just a verb plus an

adverb.

If as a learner of English you encounter, for example:

She put the fire out

you would be right to think something like:

Aha! This means that put plus out takes on a new meaning (something like extinguish)

and you would be wholly correct and quite wise to try to learn the verb put out as having something to do with fire and flames.

If, on the other hand, you come across:

She put the cat out

you would be unwise to try to learn put out as a verb which has anything to do with cats. You would be much wiser to realise that put has its normal meaning and the adverb out simply tells us where the cat was put.

(Of course, if the cat in question was on fire ...) - The second problem follows on and is to do with loading

learners with unnecessary problems and memorisation tasks.

If you tell students that walk back, walk away, walk out, talk about, talk in etc. are all phrasal verbs, then they will try to remember them separately (as you should with real phrasal verbs) but you will be wasting your time because you already know the meaning of walk and talk and the meanings of back, about, in, away and out so there is nothing new to learn and you can get on with learning something useful.

Equally, if you tell your students that a verb + any prepositional phrase, any adverb or any particle (or, even, an adjective) is a phrasal verb, they will think they have to learn it as a unit. They will then be stuck with learning lots of 'verbs' which aren't verbs at all but simply combinations of verbs and prepositional phrases or verbs modified by adverbs. It's like teaching people that turn right and turn left are examples of two different verbs or eat butter and spread butter contain examples of two different nouns.

You will be denying the learners the opportunity properly to analyse what they are learning and notice how prepositional phrases and adverbs are used in English.

Misleading learners is not forgiveable and made worse if the misleading results in an extra and unnecessary learning load.

That is not to say that learning a collocating language chunk such as run away, meaning flee, is not useful but it bears repeating that any common combination of verbs and modifiers is not necessarily a phrasal or multi-word verb. The word lots, for example, collocates very strongly with the preposition of and so lots of is a useful, learnable language chunk but it is not in itself a determiner. If it is treated as such then the category of determiner becomes inflated to include less of, little of, few of, many of, some of, none of, all of and so on. That would be an unacceptable analysis which will overload learners uselessly.

English is hard enough to learn without people making it harder.

|

An overview summary of the definitions used in this guide |

Four structures have been extensively discussed above so now it

is time to draw breath and look at the definitions that we will use

to analyse multi-word verbs in what follows.

It looks like this:

| Verbs plus prepositional phrases For example: She drove over the hill |

Verbs plus modifying adverbs For example: She drove back |

|

|

| Prepositional verbs For example: He relied on my help |

Phrasal verbs For example: She put the meeting off |

|

|

Only the second two of the types above are multi-word verbs.

There is a third sort which combine the natures of prepositional and

phrasal verbs as we shall see.

The first two structures will not be considered in the core of this

guide because they

are not examples of multi-word verbs (whatever you may read on the

web).

|

Clause constituents |

Briefly, if the term is unfamiliar to you, clause constituents are phrases or single lexemes within a clause that perform a single, identifiable grammatical function.

So, for example, in:

John changed money yesterday

we have four constituents:

- John: a single proper noun performing the grammatical role of subject

- changed: a past form of a verb performing a verb's usual function of denoting an event or state

- money: a single mass noun performing the grammatical role of object

- yesterday: a single common noun performing the grammatical role of adverbial time adjunct

Equally, we can have a sentence such as:

John, the manager, and his elderly mother will have

changed a considerable amount of money by this time tomorrow

and we still have only four clause constituents:

- John, the manager, and his elderly mother: a noun phrase with the first noun in apposition to another and the second noun pre-modified by an adjective performing the grammatical role of subject

- will have changed: a verb phrase with two auxiliary verbs and a main verb performing a verb's usual function of denoting an event or state

- a considerable amount of money: a noun phrase pre-modified by a quantifying expression and post modified by a genitive of phrase performing the grammatical role of object

- by this time tomorrow: an adverbial phrase of time performing the grammatical role of adverbial adjunct

Identifying clause constituents in the realm of multi-word verbs is a helpful way of identifying what part of the clause is doing what and helping us not to fall into the traps we have discussed above. It works like this:

|

What is not a multi-word verb phrase |

These three sentences do not contain multi-word verbs:

so, arrive at is not a multi-word verb and the preposition

at is not part of the verb phrase. It is part of the

prepositional-phrase adverbial.

so, call back is not a multi-word verb and the adverb

back is not part of the verb phrase because it is an

independent constituent of the clause modifying the verb call

whose base meaning is not altered. It can be omitted and still

leave a well-formed and meaningful sentence.

so, the adverb back may be moved but still is not part of

the constituent verb phrase because it still forms a constituent by

itself. It can, again, be omitted and still leave a

well-formed and meaningful sentence.

|

What may be considered a multi-word verb phrase |

In some analyses, this example is considered to contain a multi-word verb phrase:

because the preposition about is very strongly associated

with the verb complain and the unit can be learned as a chunk.

However, the preposition is still not part of the verb phrase

constituent because it can be substituted as in:

The old man complained of the cold

and left out altogether as in:

The old man complained

and that leads to an alternative analysis which includes the

preposition as the head of the prepositional phrase, about his

room.

|

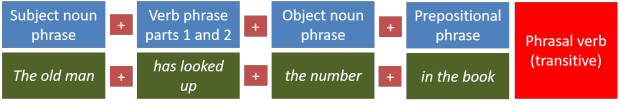

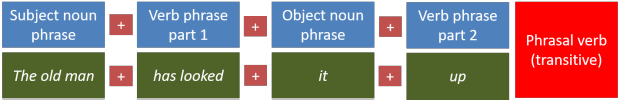

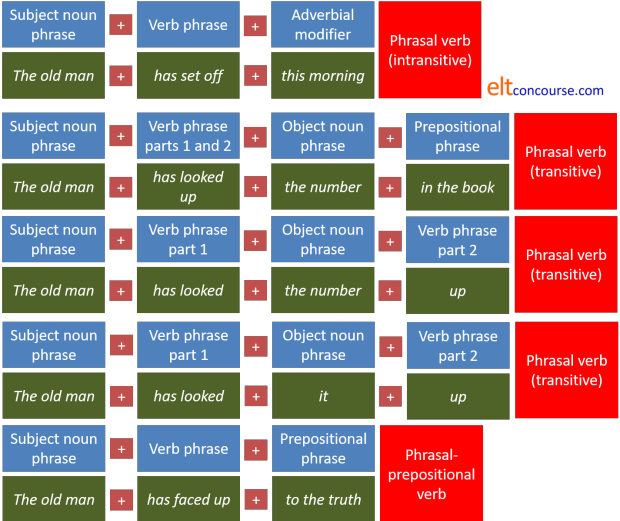

What is a multi-word verb phrase |

The following are, indubitably examples of multi-word verbs, however:

because the adverb off is an integral part of the

verb-phrase constituent. If it is omitted, the sentence

carries no meaning and is ungrammatical.

because the adverb up is part of the verb-phrase

constituent. If it is omitted, the sentence carries no meaning

and is ungrammatical.

because even when it is split from the first part of the phrase, the

adverb up remains part of the verb-phrase constituent.

If it is omitted, the sentence carries no meaning and is

ungrammatical.

and it does so again here because the only change is to use a single

pronoun to stand for the number. Nothing else has

changed.

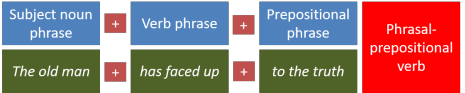

because we clearly have an integrated verb and adverb forming the

verb phrase followed by a simple prepositional phrase. The key

here is that the preposition to belongs with the truth

not with the verb-phrase constituent.

However, as with prepositional verbs, the preposition to is

very strongly associated with the phrasal verb face up and

the expression face up to is a learnable chunk. That

does not influence the analysis, because we are talking about a

teachable unit not clause constituent analysis.

If you would like to see all these little diagrams in one place, they are available at the end in the summaries.

|

Categorical indeterminacy or gradience |

This nasty expression refers to the fact that it is sometimes quite

difficult to pin down a word's word class. We can rarely tell by

looking at a word in isolation which word class it belongs to so, for

example, bank is a verb in

I bank in the High Street

and a noun in

He went to the bank

and the same phenomenon is apparent with thousands of other words in

most languages.

The phenomenon is particularly noticeable with particles in

multi-word verbs and that leads to the difficulties looked at in the

last section because many common adverbs are also prepositions in other

environments and vice versa.

The eleven most common particles in multi-word verbs are:

around, at, away, down, in, off, on, out, over, round, up

and all bar the preposition at and the adverb away may be prepositions or adverbs depending on their grammatical function in a clause. Like this:

| particle | as a preposition | as an adverb |

| around | He walked around the town | They fell around laughing |

| at | He complained at reception | Not possible |

| away | Not possible | She's gone away |

| down | He came slowly down the stairs | They broke the figures down |

| in | He left it in the suitcase | She filled the form in |

| off | He took it off the table | The bomb went off |

| on | She left it on the table | She switched on the light |

| out | They climbed out the window | I must speak out |

| over | The dog jumped over the wall | Please turn the page over |

| round | The man appeared round the corner | They talked me round |

| up | We drove up the road | We finished the food up |

The words into and onto do not appear in this list because

they never

function as adverbs. They are prepositions. We can have:

He brushed the paint on

He pushed the drawer in

and the words on and in are functioning as adverbs

telling us a bit about the verb.

We can also have:

He brushed the paint onto the door frame

He pushed the drawer into the desk

and the words onto and into are prepositions.

However, we cannot have:

*He brushed the paint onto

*He pushed the drawer into

because neither word can function adverbially.

The list of words which some describe as prepositional adverbs (i.e., those that can perform both functions) is:

aboard, about, above, across, after, against, along, alongside, around, before, behind, below, beneath, besides, between, beyond, by, down, for, in, inside, near, notwithstanding, off, on, opposite, outside, over, past, round, since, through, throughout, under, underneath, up, within, without

and they can all modify a verb without, necessarily, producing a

phrasal verb.

In some analyses, the distinction between adverbs and prepositions

is not maintained in this way. In that view, the words in the list above

are simple intransitive prepositions (or prepositions which allow

intransitive use). This is a defensible analysis because it is

consistent with defining the noun phrase as the object of the

preposition rather than its complement.

A test to see which grammatical function a word is performing is to

add a complement (or object, if you prefer) to the word. If it's

possible to do so, you have probably identified a preposition because

adverbs do not take complements or objects. So for example, we can

have:

He came over

and that's an adverb modifying the verb

He came over the road

and that's a preposition with its complement / object the road telling us where

he came.

Unfortunately, when it comes to phrasal verbs as we shall see, the

picture is not so clear so while in, for example:

He gave up the job

it looks as if we have a preposition, up, with a complement,

the job, but that is not the case because here the word is an

adverb which combines with the verb give to form a new verb

give up (meaning abandon) and the job is the

object of the verb give up, not a complement or object of a preposition.

In our analysis, this is a key factor in assigning verbs to the

categories of phrasal verbs (verbs combining with adverbs) and

prepositional verbs (verbs followed by prepositions).

Another key test is to try replacing the particle with a different one or

removing the particle altogether to

see if the sense of the verb has altered. If it has, we are

dealing with an adverb combining with the verb to form a phrasal verb.

If it hasn't, the particle is prepositional. So, for example,

changing the particle in:

He walked slowly up the stairs

to make

He walked slowly down the stairs

He walked slowly along the stairs

He walked slowly by the stairs

etc. has no effect at all on the meaning of walk.

However, changing the particle in:

He put off the meeting

to make

He put down the meeting

He put into the meeting

*He put along the meeting

or leaving the particle out to make:

*He put the meeting

etc. either changes the meaning of the verb or makes nonsense.

A final test is to spot the stressed forms. Adverbs are

usually stressed but prepositions are not. We get, therefore:

He talked of his childhood

in which of is unstressed and pronounced as /əv/ but

What did he talk of?

in which of is in its full form and stressed as /ɒv/.

There are times when two or more adverb particles are possible

without a change in meaning so we can have, for example:

They fell around laughing

or

They fell about laughing

and

They set off early

or

They set out early

with little discernible difference in meaning although in both cases the

particles are adverbs.

Fortunately, this is quite rare.

|

The triple nature of MWVs |

Now we are ready to begin the analysis proper. The following summarises the story so far and more detail follows.

- Phrasal verbs

The adverb particle changes the meaning of the verb and the change is often non-literal, i.e., idiomatic. For example, adding the adverb down to the verb turn produces the new meaning of decline (an offer). Prepositions do not do that.

Nor, as we saw above do all adverbs. Only adverb particles vary the meaning of the verb. We saw above, and will see again, for example, that the adverb back does not always change the meaning of the verb it follows. Nor, incidentally does an adverb like away which simply means to a distance from. So, although:

He walked away

looks like a phrasal verb, it is not because the adverb is just telling us the direction in which he walked and not interfering with the meaning of walk at all. By the same token, we can have:

She ran away

He drove away

They strolled away

It flew away

and many more examples of a one-word adverb modifying but not changing the meaning of the verb. If we call all these examples phrasal verbs, we will be adding hundreds if not thousands of verbs to a list which is long enough to depress many learners and teachers already.

Even a metaphorical use of the verb does not magically result in a phrasal verb so

He walked away with first prize (won easily)

or

He ran away with the game (became unbeatable)

are not really phrasal verbs but are, as we shall see, metaphorical uses of a verb plus an adverb.

However, when the meaning of the verb changes, we have encountered a real phrasal verb so, while, e.g.:

He gave the money away

is comprehensible by understanding the meaning of away as and adverb meaning movement to a more distant place, so it is not a phrasal verb. It is possible in this case, to find a one-word alternative (using test 9) so we could have:

He donated his money

but that does not carry quite the same sense because the verb is usually followed by a prepositional phrase complement (such as to charity).

If we try to do that with

He gave the secret away

we can see that the meaning of the verb has changed because the meaning of give and the meaning of away have combined to make a new meaning (revealed). That is a real phrasal verb. - Prepositional verbs

Prepositions link the verb to a noun phrase but the choice of preposition is strongly determined by the verb (which is why they are sometimes called verbs with dependent prepositions). They do not change the meaning of the verb.

For example, adding the preposition about to the verb hear does not change the nature of the verb:

He heard about the disaster

and changing the preposition will leave the verb's meaning unchanged

He heard of the disaster

He heard from his parents

Some of these verbs allow of only one preposition as is the case, for example, with:

She relied on his help

in which no other preposition is possible.

Some of these verbs, as we shall see, require complementation and cannot stand without a prepositional phrase. - Phrasal-prepositional verbs

The adverb particle changes the meaning of the verb and the preposition links the verb to a noun phrase. For example, adding the adverb up and the preposition with to put changes the meaning of the verb and links it to the noun phrase:

He couldn't put up with their noise any longer

(verb + adverb, making a phrasal verb, followed by a prepositional phrase)

Later, some doubt will be cast on whether this is a real category or a phrasal verb followed by a strongly collocating preposition.

Here's a summary of that with examples:

Later, you will find slightly more sophisticated summary diagrams which deal with verb types, transitivity and separability, err, separately.

|

Distinguishing phrasal from prepositional verbs |

If the multi-word verb isn't a prepositional verb then it's either a phrasal

verb or a phrasal-prepositional verb. To know which it is, we need

to look at how it's used.

In this area, we need to consider 5 constituents of the

clause:

- The subject (either a pronoun or a noun phrase such as She or The old man)

- Verb phrases such as pushed

- The particle, which can be an adverb or a preposition, such as up, for, away, over etc.

- Object nouns such as the lever, the boat etc.

- Object pronouns such as it, them etc.

For our purposes, we can ignore the subject.

Given that we place the subject and the main verb first in the clause, there are,

in English, only 4 possible arrangements of particles and objects

to finish the clause.

See if you can arrange the following to make a well-formed English

sentence:

He + the + lever + up +

pushed

He + it + for + pushed

He + boat + the + away + pushed

He + over + pushed

+ them

What are the alternatives? Click

here

when you have an answer.

| Pattern 1 | subject + verb | + | particle | + | object noun |

| He pushed | + | up | + | the lever | |

| Pattern 2 | subject + verb | + | particle | + | object pronoun |

| He pushed | + | for | + | it | |

| Pattern 3 | subject + verb | + | object noun | + | particle |

| He pushed | + | the boat | + | away | |

| Pattern 4 | subject + verb | + | object pronoun | + | particle |

| He pushed | + | them | + | over |

The key identifying pattern is Pattern 4.

The verb has been split from its particle by an object pronoun and that

is one defining characteristic of most transitive phrasal verbs, but ...

|

... this is not a unique characteristics of phrasal verbs |

Before we get too excited about the fact that a pronoun

must be placed between the verb and the adverb particle, we need to

consider that this is not something unusual or unique to phrasal

verbs. Pronouns frequently appear in this medial position when

a verb is modified by an adverb. For example:

She drove the car quickly

She drove it quickly

but not

*She drove quickly it

He writes emails frequently

He writes them frequently

but not

*He writes frequently them

We can see the same pattern with hundreds of other perfectly

normal adverbs modifying transitive verbs. Not even the

wildest websites will suggest that drive quickly and

write frequently are phrasal or multi-word verbs.

Simply noticing the fact that the pronoun must come between the verb and the adverb does not mean that you have found a phrasal verb.

However, a better test is possible by looking at the ordering of

constituents of a clause.

So, for example:

| Verb + modifying adverb | |||

| 1 | She drove the car quickly | = | verb + object noun + adverb |

| 2 | She drove it quickly | = | verb + object pronoun + adverb |

| 3 | *She drove quickly the car | = | verb + adverb + object noun |

| 4 | *She drove quickly it. | = | verb + adverb + object pronoun |

| Phrasal verb | |||

| 1 | She put the meeting off | = | verb + object noun + adverb |

| 2 | She put it off | = | verb + object pronoun + adverb |

| 3 | She put off the meeting | = | verb + adverb + object noun |

| 4 | *She put off it | = | verb + adverb + object pronoun |

And you can see that a phrasal verb, properly understood, allows

pattern 3. whereas a simple verb + modifying adverb normally does

not.

If we apply this test to a range of verbs + adverbs we discover, for

example, that an expressions like call back, move about, drive

ahead, push under, pull over etc. cannot be seen in

pattern 3. so are not phrasal verbs per se because:

*She called back the garage

*She moved about the furniture

*He drove ahead the car

*He pushed under the suitcase

*He pulled over his scarf

are not available, but call off is a phrasal verb because

we can happily form:

She called off the meeting.

This is not, we hasten to add, a defining characteristic of the two forms but it is a clear indication.

Unfortunately, of course, simple verbs plus prepositional phrases

such as:

She got on the bus

They fell over the carpet

etc. can also be used in pattern 3.

but this does not mean that get on and fell over

are phrasal verbs. They aren't; they are verbs followed by

prepositional adverbial phrases and we can just as well have:

She climbed on the bus

She stepped onto the bus

They tripped over the carpet

They stumbled over the carpet

She got off the bus

She got in front of the bus

They fell onto the carpet

They fell across the carpet

etc.

You can see, too, that on in all cases can be replaced with

onto and that word is only prepositional.

Now we can go on to look at which patterns are associated with which forms of multi-word verbs.

|

Prepositional verbs |

| look up the chimney |

This guide uses the term prepositional verbs for this category of multi-word verbs. Others may refer to them as verbs with dependent prepositions because the verbs are normally associated with particular prepositions. Others still may call these verbs strongly collocating verb-preposition pairs.

We need to be careful to distinguish between a verb followed by a

prepositional phrase in the normal way of English syntax and those