Teaching multi-word verbs (MWVs)

If you have followed the language analysis guide to multi-word verbs you will be aware that it is not always easy to disentangle the 3 sorts of these:

- phrasal verbs which can be intransitive (e.g., Look out!) or transitive and must be separated by the pronoun (e.g., look it up)

- prepositional verbs which are not separable and

can be transitive (e.g., account for) or transitive and

intransitive, with or without the preposition (e.g., insist

and insist on)

The main guide to multi-word verbs casts a good deal of doubt on whether prepositional verbs are, in fact, not simply always intransitive but have some members which require a prepositional-phrase complement. - phrasal-prepositional verbs which work similarly (e.g., run out of, look forward to)

Before you go on,

you should have the distinctions clear in your head.

You should also be clear why the verb in He turned down the lane

is not a multi-word verb but the one in He turned down the offer

is.

You have to understand this area before you can hope to teach it

successfully.

|

Why are MWVs difficult for learners? |

One obvious reason is that lots of languages don't have them.

Something like MWVs do exist in a number of Germanic languages (of which

English is one) so learners with those language backgrounds will not be surprised

by them. Usually, in these languages, these sorts of verbs are

simply called separable verbs. There is some evidence of a few

verb + particle combinations in Polish, Italian, Spanish and French but

they are not of the type of complexity and commonness we find in

English.

Other languages (Japanese and Hindi, for example) do exhibit something

called compound verbs made up of two related words but they are a far

cry from multi-word verbs in English.

In summary, most learners of English will find MWVs novel and taxing to

learn.

There are consequences of interlingual differences:

|

Avoidance and overuse |

Learners whose first languages do not have parallel multi-word verb forms will, predictably, tend to avoid them and rely more heavily on single-word equivalents such as postpone for put off or divide for split up and so on. Communicatively, this may still be effective but stylistically there are clear problems because most single-word equivalents are significantly more formal in English than the multi-word verb structures.

On the other hand, learners from Germanic language backgrounds (such as Dutch and German speakers) my overuse phrasal verbs in English because they are not alert to the stylistically informal nature that many exhibit. In both Dutch and German, multi-word verbs are not specifically marked for formality at all and are neutral. This results in the opposite problem and such learners may be unable to adopt a suitably neutral or formal style when needed.

|

Synonymy |

While the use of synonymy in classrooms as a short-cut to meaning

is often effective, there are obvious perils when it comes to

multi-word verbs. For example, it is often averred that:

find out = discover

get by = manage

and so on.

However, this may result in errors such as:

*We have to find out a new method

*They have to get by the problem somehow

|

Collocation and context |

Multi-word verbs and their one-word equivalents often collocate

in unpredictable ways so, for example while we can have:

establish a company

set up a company

establish the truth

establish a garden

and so on, we cannot allow:

*set up the truth

or

*set up a garden

We can also allow:

select the best bits

pick out the best bits

select a new method

but do not allow

*pick out a new method

and so on.

Here is an example of MWVs in action, taken from the language analysis guide:

| Pattern 1 | subject + verb | + | particle | + | object noun |

| He pushed | + | up | + | the lever | |

| Pattern 2 | subject + verb | + | particle | + | object pronoun |

| He pushed | + | for | + | it | |

| Pattern 3 | subject + verb | + | object noun | + | particle |

| He pushed | + | the boat | + | away | |

| Pattern 4 | subject + verb | + | object pronoun | + | particle |

| He pushed | + | them | + | over |

Think for a moment and come up with one problem relating to form and

one to meaning which will make this sort of language difficult for

learners. If you can think of more than one problem in each

section, that's good.

Click here when you are ready.

|

Form problems |

-

Separability

We can have

He pulled up the lever

and

He pulled the lever up

but

*He pushed it for

and

*He pushed over them

are not possible (and

?He pushed away the boat

is a slightly doubtful case.

Learners have to know a) what sorts of MWVs are separable and b) what can be used to separate the verb from its particle.

Many phrasal verbs must be separated from their particles when the object is a pronoun. We can't have

*He looked up it in the dictionary

When the object is not a pronoun, the verb can optionally be separated so we can have either

He looked the word up

or

He looked up the word.

A combination of a verb plus a preposition, on the other hand, is not separated by the object at all so we can't have

*He looked it at

or

*He looked the timetable at

and prepositional verbs follow the same pattern so we allow:

She counted on my help

and

She counted on it

but forbid

*She counted my help on

and

*She counted it on

The same applies to phrasal-prepositional verbs such as run out of.

That's just hard to learn.

The result of the complication is that learners will separate when they shouldn't or not separate when they should.

Partly, the issue may be teacher induced. If learners are told that look at is a phrasal verb, then they can be forgiven for treating it as one. -

Transitivity

We can have

He pulled up the lever

and

He pulled up at the parking space

but intransitivity in the second case changes the verb's meaning.

Intransitive phrasal verbs, which are analysed in this site as akin to prepositional verbs, structurally speaking, such as those in

The plane took off

The car broke down

Get up early

etc. are possibly easier to learn because there's no problem with separability of course, but remembering which particle goes with which for each meaning is still difficult.

There is also a problem with the inappropriate insertion of adverbs:

*He's growing quickly up

Prepositional verbs are a different matter. In the analysis, the following point was made:

There are two way of analysing the verbs which insist on a prepositional complement and both are sustainable (and teachable):- as verb plus object:

Mary relied on her brother Subject Verb Object - as verb plus obligatory prepositional-phrase complement:

Mary relied on her brother Subject Verb Preposition Prepositional object or complement

Some are always transitive and take their particle with them wherever they go. For example, rely on, account for and long for are always transitive and occur with the prepositions.

Others are less accommodating. For example, insist, object and complain can be used intransitively

I insisted / objected / complained

but when they take an object, learners need to remember which preposition to tack on to the verb (on, to, about, respectively).

One result of this complication is that learners may pick the wrong particle. If I can say

She objected to the price

why can't I say

*She complained to the price?

Another result is that learners will use intransitive verbs transitively

*I insisted the changes

*I argued him

and the other way around

*I relied the information

Often, this is because transitivity is variable across even closely related languages.

To add fuel to the fire, many verbs can be used both ways. For example, something can blow up and you can blow something up. Some will also change the meaning when transitivity changes: work out means to discover something when it's transitive but means either exercise or succeed when it's used intransitively. - as verb plus object:

-

Pronunciation

In phrasal verbs (rather than prepositional verbs) we do not usually reduce the vowel in the particle to its weak form. Compare the pronunciation of to in

He came to the party

and

He came to after the operation. -

Where does the verb stop?

It's not always easy for learners to identify which bit is the MWV and which is a following prepositional phrase. In something like

He pulled up by the church

some might be tempted to try to learn pull up by as a MWV and produce

*He pulled up by outside

After all, we can have three-part phrasal-prepositional verbs such as get on with, stick up for and put up with so it's not a mysterious error.

The reason for it is that the learner has not recognised that by the church is a prepositional phrase replaceable by many others (in the garden, on the bridge, outside the police station etc.) and up here is an adverb particle. Telling learners about prepositions and adverbs is rarely productive. It's better to make sure that the presentation and practice make the distinctions clear – context and co-text, yet again. -

Where is the verb?

This appears under Form but could just as well be under Meaning. Consider a sentence like

They had to give their dream of saving up enough money to buy their first house in London up

The main verb here is give up but the object (the dream of saving up enough money to buy their first house) separates the particle from the verb by 14 words. There's also another intransitive MWV (save up) in the sentence to confuse the learner.

|

Meaning problems |

-

Noncompositionality

That's a nice, long technical word which simply means that many MWVs cannot be understood by knowing the meaning of the verb and the usual significance of the particle. This is not always true: some MWVs are transparent in meaning and some are wholly opaque but most fall somewhere in between.

For example,

Care for my cat

can be readily understood, providing one knows the verb, as can

Load up the car

but

Don't put up with it

is probably completely opaque even if one knows the meanings of put and up, and

Stand by your decision

is only interpreted with some understanding of metaphorical use. The fact of the matter is that most so-called opaque meanings can be traced to a more transparent use of the MWV, often a prepositional use which has developed other, adverb, meanings. -

Polysemy

While not unique to MWVs, of course, multiple meanings of a single item can cause problems. For example, give in can be used transitively to mean hand in (an essay, for example) and intransitively to mean surrender. In the same way, we can have

I'll break down the figures

and

The car broke down

This problem is also one of form because the meaning in which the verb is used may affect transitivity and separability. See above under transitivity for another example.

This also applies to the particles. For example, the distinction between I give up and I give in is sometimes so subtle as to be almost invisible. -

Style

It is often stated that MWVs are stylistically less formal than any one-word equivalents. That's often true but not always the case. Corpus research has done much to explode this myth. MWVs appear in even the most formal academic texts and, in any case, there isn't always a one-word equivalent for some MWVs. For example, what one-word equivalent can you think of for slow down, take off (clothes), deal with, consist of?

A term such as slow down, for example, is just as likely to appear in an academic text as an informal text. In fact, decelerate, is really very uncommon. The truth of the matter is that MWVs are not some kind of substandard colloquialisms; they are important and indispensable lexemes in their own right.

Learners who have been told that MWVs are always informal may be tempted to produce pompous prose such as

She donned her track suit

rather than using put on in a natural way.

And, in an effort to substitute a one-word equivalent and avoid using a MWV at all, learners can also sound overly formal and distant.

The moral: don't give learners half-truths. Treat each item in terms of its style as you would for any lexis. -

Collocation

Allied to the style issue is the one of collocation. Many MWVs and their one-word 'equivalents' collocate very differently. For example, this is OK:

He decelerated coming into the hairpin

but this is not acceptable:

*He knew he was talking too fast for me to understand so he decelerated

As another example, you can call off a wedding, a party, a meeting and a trip but you can't naturally call off a holiday or a private lesson. Then you have to use cancel.

|

Which verbs to teach and which particles?PVs are both very important and very

difficult to learn |

| pick one out |

The bad news:

Estimates of the number of phrasal and prepositional verbs in

English vary but corpus research has helped a good deal in

pinning things down. There are, according to some surveys,

around 5,000 to 10,000 in total and that is clearly an

impossible target even to consider.

There is a need, therefore, to be very selective in our

approach.

The good news #1:

Many of the verbs identified by corpus researchers are uncommon and

the even better news is that a little common sense will alert you to

the fact that the adverb particles often mean exactly the same thing

across a range of verbs which corpus research would identify as

separate items. We saw in the guide to the analysis of this

area that the phrasal verb take off, meaning remove as in,

e.g.:

I took off the sticky label

is akin in meaning to at least:

| brush off chip off chop off cut off dust off hack off |

knock off polish off rub off scour off scrape off scratch off |

scrub off slice off sponge off sweep off wash off wipe off |

and it is clearly unnecessary to teach each of these as a

separate item. Learn one and you have learned them all.

We do not have 18 phrasal verbs here; what we have is one meaning of

the adverb off combining with 18 verbs.

This sort of analysis will not, of course, lead learners to

understanding something like

He took the Prime Minister off hilariously

but that is quite a rare item in any case.

The good news #2:

Corpus research has also discovered that

20 lexical or main verbs, combined with only eight

particles (out, up, on, back, down, in, over, and

off), account for

more than half (50.4%) of the PVs in the BNC. Looking at individual

PV lemmas (e.g. pick up, go on), [other

researchers] found that only 25 make up

nearly one-third of all PV occurrences in the corpus, and 100 make

up more than one-half (51.4%).

Ibid:7

(The BNC is the British National Corpus of around 100 million

words in British English based on spoken and written samples.

A lemma is the technical term for a dictionary entry for a word so,

for example, speak is the lemma entry but will include

spoke, spoken, speaking etc.)

This actually reduces the load on learners very considerably because we now have a teachable target of around 150 verbs only.

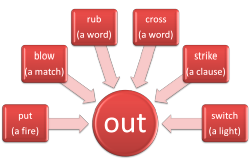

The good news #3:

Researchers often ascribe separate meanings to phrasal verbs which

can be seen, with a little imagination, to constitute the same

meaning. For example, some will ascribe two meanings to the

verb put out in:

I put out the light

and

I put out the fire

whereas a little thought reveals that there is only one basic

meaning at work here. Moreover, if a learner has grasped that

the adverb out has a specific sense of causing absence or

disappearance (compare rub out, strike out, scratch out, cross

out etc.) then the meaning becomes more transparent.

The good news #4:

If we select from the 100 most common verbs in English only those

that conventionally combine with adverb particles to form phrasal

verbs we get a list of 56 verbs like this:

| Verbs | Particles | |||

| add ask be bring build buy call come cut die do fall feel follow |

get give go grow have help hold keep leave let live look make meet |

move open pass pay pull put reach read run see sell send set show |

sit speak stand start stay take talk tell turn use wait walk work write |

back down in off on out over up |

Of course, if all the verbs combined with all the particles, this would still represent 448 different phrasal verbs to learn and teach but ...

The good news #5:

They don't all combine with all the particles. For example,

the verb add only naturally combines with in and

up and leave only combines with in, off

and out.

The majority of the verbs will only combine with half or fewer of

the adverb particles so, immediately, the targets are reduced to

around 200 possible phrasal verbs and that is an attainable number

when one considers that learners at level A2 on the Common European

Framework are expected to have mastered around 2000 words. By

C1, this total rises to over 4000 words of which only 5% would be

phrasal verbs in our sense of the term.

The good news #6:

In many cases, we are not dealing with phrasal verbs of impenetrable

meaning, if we are dealing with them at all. For example,

expressions like:

I'll call back

Please stand up

When will you get back?

She ran back

He wasn't in

etc. are simple to understand and produce because the adverb is

functioning in its central meaning. Compare, e.g.:

I'll ring / phone / write / email back

Please stand here / there / outside

When will you get here / there / home?

She ran there / here / back / away

He wasn't out / there / here / outside

etc.

By our definition, these are not examples of phrasal verbs at all.

They are simply verbs post-modified with adverbs.

The good news #7:

The PHaVE list consists of 150 phrasal verbs and seems to be freely

available at

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B7FW2BYaBgeiMkphZXFOM2V2bTA.

The slightly less good news is that each verb in the list has an average

of just under 2 possible meanings but, even if we assume that a

different meaning of a phrasal verb has to be separately

learned, that still leaves a target of fewer than 300 verbs to learn.

That's doable especially when one considers that some of the verbs in

the list (such as get on / off the bus) are not really phrasal

verbs at all.

Usefully, too, the PHaVE list gives a guideline concerning which meaning

of each verb is more frequent as a percentage. For planning

purposes, that's helpful.

The good news #8:

At the outset at least learners can be led to the structural aspects

of multi-word (and particularly phrasal) verbs by focusing on those

whose meaning is transparent. This means that multi-word verbs

such as bring up, pick up, set up, get up and so on can be

taught simply once the learners are aware of the meaning of the

adverb particle up parallels its familiar use as a

preposition.

The summary:

If we extract the verbs only from the PHaVE list, we end up with 62 verbs

forming 150 combinations (some of which will be polysemous). The

issue of distinguishing when and whether one meaning of a multi-word

verb is different from another is also important. For example, the PHaVE list suggests that the meaning of set up is different in:

An advisory committee is being set up

from the meaning in:

We need to set up a few more chairs so everyone can sit

down.

and that's arguable, at least, because many would suggest that the verbs

are synonymous rather than polysemous in those examples, the former

being slightly figurative but transparent in meaning.

As is pointed out in the guide to polysemy on this site:

the problem of distinguishing between

homonymy and polysemy is, in principle, insoluble.

Lyons, cited in Laufer, in Schmitt and

McCarthy (1997:152)

Some of them will also be prepositional rather than phrasal verbs

because the list does not distinguish between them.

Here they are:

| Verb | + | Particle(s) | Verb | + | Particle(s) |

| come | through | move | back / in / on / out / up | ||

| back | up | open | up | ||

| blow | up | pass | on | ||

| break | off / out / up | pay | off | ||

| bring | about / back / down / in / out / up | pick | out / up | ||

| build | up | play | out | ||

| call | out | point | out | ||

| carry | on / out | pull | back / out / up | ||

| catch | up | put | back / in / off / on / out / up | ||

| check | out | reach | out | ||

| clean | up | rule | out | ||

| close | down | run | out | ||

| come | about / along / around / back / down / in / off / on / out / over / up | send | out | ||

| cut | off | set | about / down / off / out / up | ||

| end | up | settle | down | ||

| figure | out | show | up | ||

| fill | in / out | shut | down / up | ||

| find | out | sit | back / down / up | ||

| follow | up | slow | down | ||

| get | back / down / in / off / on / out / through / up | sort | out | ||

| give | back / in / out / up | stand | out / up / out | ||

| go | ahead / along / around / back / down / in / off / on / out / over / through / up | step | back | ||

| grow | up | sum | up | ||

| hand | over | take | back / down / in / off / on / out / over / up | ||

| hang | on / out / up | throw | out | ||

| hold | back / out / up | turn | around / back / down / off / out / over / up | ||

| keep | on / up | wake | up | ||

| lay | down / out | walk | out | ||

| line | up | wind | up | ||

| look | around / back / down / out / up | work | out | ||

| make | up | write | down |

The problem with lists, naturally, is that they don't contribute to

analysis insofar as the items are not classified by separability,

transitivity or form.

Some of the above, such as get back (in the sense of return)

are just a verb plus a modifying adverb and do not need to be learnt as

special or intimidating combinations because we can just as well have

run back, drive back, walk back, stroll back and a huge range

of other verbs which refer to movement.

Others, such as get on and get off (embark

and disembark very roughly) are analysable as verbs plus

prepositional phrases because we can have on / off the boat / train

/ tram / roundabout / liner / plane / ferry etc. and, again, do not

need to be learned as combinatory meanings in the same way that get

on meaning make progress does.

|

Teaching multi-word verbsNow that we have a sort of syllabus, we need to get on to teaching the forms. |

|

Don't do it! |

There's quite a strong argument in favour of not deliberately focusing on MWVs at all but treating them as and when they arise in the same way as any other lexeme. This view is based on some underlying beliefs:

- that MWVs are so complex in form and meaning that any lesson which attempts to cover the ground is doomed to fail

- that learners will become disheartened and demoralised by the sheer number of form and meaning complexities

- that focusing on a single verb such as set and then adding particles to it (set off, set up, set by etc.) will actually encourage confusion

- that, equally, focusing on a particle and then on verbs that go with it (set down, bring down, put down, hold down etc.) will be confusing

What counter arguments can you develop for these four views? Think for a moment and then click here.

Here are some thoughts:

- Yes, MWVs are complex but so are a number of

structures in every language (tense forms and affixation rules in English, cases in German, irregular verbs in Greek

etc.) but that doesn't stop you

teaching them. It's just a matter of breaking

things down and teaching bit by bit.

Secondly, the meaning issue only applies to verbs which are opaque and idiomatic in meaning. The majority of phrasal verbs are neither.

Thirdly, the structural issue for most transitive phrasal verbs boils down to the need to insert any pronoun object between the verb and the particle and that's not too difficult to learn because the other three possible patterns are all acceptable. - If this is true, then we wouldn't teach words at all. There are thousands of them and they nearly all have associated grammar and collocational issues. We have also seen that the core multi-word verbs (listed above) do constitute an achievable teaching target.

- This may be true if you overdo it (as some coursebooks do) but teaching sets such as drive off, drive back, drive away, drive over, drive by etc. makes perfect sense in terms of how the brain stores concepts together.

- But actually, as we saw, the particles often do have similar meanings with a range of verbs. For example, off is usually associated with a concept of detachment or separation in verbs like break off (a piece), put off (a meeting), switch off (a light), turn off (a tap), take off (leave the ground), call off (a dog), clear off (go away) etc.

Even if you take the first view, you are going to have to deal with MWVs in some way or other. If you take the second view, i.e., that we should focus on this important and difficult area explicitly, then we need some strategies to help. Here are some ideas.

|

Plan and focus |

There's little point in planning a lesson which includes separable, transitive, prepositional, phrasal and phrasal-prepositional verbs all in the same materials – that will confuse your learners. So introduce verbs which share formal characteristics together.

- Dealing with separability and intransitivity.

Idea 1

You could focus a lesson on transitive prepositional verbs such as abstain from, comment on, quarrel about, react to and talk about in a lesson on the topic of friends meeting and talking to plan an event or a formal meeting to discuss a local problem or whatever. It's not difficult to develop a text containing them if the context is clear. For example:

They met to talk about the party they were planning for John's 50th but soon began quarrelling about whether it should be a surprise or not. Mary, in particular reacted badly to the idea saying that John hated being surprised by events like this ...

etc.

All these prepositional verbs share a common structure: they are both transitive and inseparable. Your learners will not be tempted into mistakes such as

*They talked the problem about

by analogy with a transitive separable phrasal verb such as in

They tossed the ball about. - Dealing with separability and intransitivity.

Idea 2

Equally, you could plan a lesson which does focus on separability of transitive MWVs such as call off, think through, call up, count in, pass on, set up etc. and the same idea of planning a party for someone would work well as a topic to hang it on along the lines of:

They decided not to give the party idea up but to set it up for the following Saturday. Unfortunately, they had to call the event off when it was clear ... etc.

All these phrasal verbs share a common structure: they are both transitive and separable. - Dealing with noncompositionality.

Idea 1

Focus on a particle, such as the example of off above, and choose to introduce verbs which show the gradual transition from literal to metaphorical meaning.

For example, for the idea of progress towards a target, you could select get on, then go on, then carry on, then keep on, then move on then hurry on. The idea that on often has the sense of towards a goal (but some meanings are slightly metaphorical) is easy to grasp.

It is also the case, incidentally, that the particle on carries aspectual meaning and suggest a progressive sense.

Later, you could select another meaning of on, that of connection or joining, and introduce tie on, stick on, turn on, switch on, hold on etc. If you look at the table concerning the meanings of adverb particles in the analysis guide, you'll find some more candidates.

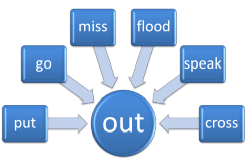

Although it looks nice, the following sort of presentation is flawed

for two reasons:

a) we actually have multiple meanings of the particle out (exit, emerge, clearness, disappearance) and

b) there's no exemplification or context to help the learners.

There's nothing wrong in principle with this kind of presentation or in getting your students to construct one but you have to maintain focus and contextualise with examples. It would be better like this

because here we have one meaning only of out (the idea of making something disappear or go away) and there are examples to help the learners. - Dealing with noncompositionality.

Idea 2

If you focus on a verb rather than a particle then you need to show the connected meanings of the particles in the same way. You can, for example use the sense of break (as in destroy or interrupt) to show how the particles alter its meaning with, e.g.:

break into a meeting

break out of a meeting

break up a meeting

and then go on to try a different verb such as call with

call someone up

call on someone

call someone in

etc. There are (in)separability issues with this approach with both verbs.

You can use the same kind of presentation (or get your learners to construct one) as above but again, you need to keep the focus and exemplify. - Dealing with polysemy

Try to make sure that the materials you use don't confuse, especially at early stages. It may be tempting to add, when explaining

The car broke down

"But understand that this verb can be used with an object to mean something completely different, you know."

but that's very rarely helpful. Make sure you have context and co-text to help understanding and do not over-complicate the issue. - Dealing with collocation and style

Not telling learners that MWVs are always informal is a good beginning (see above).

When you do use the one-word equivalent to explain, e.g., the meaning of speed up as accelerate, make sure that you focus on the fact that you can't accelerate your speaking or reading but you can accelerate a car or an object in a physics lesson. - Remembering the particles

Intransitive phrasal verbs and transitive prepositional verbs are not separable. In the first case, of course, because they have no object. This means they can be taught, practised and remembered as single items.

There's no need to teach people that

I wake up at six every morning

is an example of wake plus an adverb particle. It, along with a host of other verbs can be taught as a single word with a space in the middle.

Equally, rely on, account for, talk about etc. can be taught and practised as if they were single words.

Doing this may help your learners not to separate the verbs with other adverbs and say things like

*I get early up

*She relies definitely on him

and so on.

It is possible to use adverbs in this way

She talked loudly about ...

but never necessary so why confuse people when they are acquiring the system? Such subtleties can wait till advanced levels (or even longer). - Finding the verb.

Idea 1

If you are dealing with a complex expression such as

He dropped me off by the cinema

get students to notice the difference between a preposition introducing a phrase such as by the cinema and get them to come up with alternatives (near, next to, opposite the cinema etc.).

That will help them to understand that drop off is actually the verb they should learn. - Finding the verb.

Idea 2

The problem of verbs being separated by lots of text from their adverb such as the example:

They had to give their dream of saving up enough money to buy their first house in London up

is not easy to tackle but once the learners are alerted to the fact that the meaning of the main verb is relinquish, they can begin to look for the MWV that they know. Exposure to already known MWVs in this kind of environment is useful but if the MWV is not known it's far too challenging to find it. Build up the challenge slowly and focus on simple ones that are already familiar in sentences such as

He handed his essay in

He handed his essay and the ones that his classmates gave him in

He gave sweets away

He gave all the sweets, the chocolate, the cakes and most of the rest of the food away

An alternative is to start with a 'normal' ordering such as

They had to give up their dream of saving up enough money to buy their first house in London

and then focus on the fact that it is possible to move the particle to the end without changing the meaning. Then get the students to do it with, e.g., a sentence or two like

He pointed out the new buildings and many of the other surprising changes in the city to me.

Practice of this sort will help learners to avoid panicking when they are reading texts that do this and to keep calm and look for the particle if the verb alone is making no sense. - Noticing multi-word verbs.

Especially at lower levels and especially for learners from language backgrounds that have nothing like English MWVs, there is a risk that the verbs will not be spotted at all and that will lead learners to try to understand the verb and the particle separately to figure out the meaning. You cannot understand:

I give up

by understanding the sense of give and up.

If you have a text that you intend to mine for examples of these verbs, you need to do more than rely on learners' alertness to the forms so use some kind of highlighting device such as:The plane took off on time and, as it was a long flight, I settled down to watch a movie. Unfortunately, the steward brought the food around almost immediately and the person in the next seat decided to complain about his dinner. He also kept calling the steward over to order a drink or something up. I gave the whole idea up and turned the movie off. Eventually I dropped off and didn't wake up until we were almost there.

This way, learners can see that MWVs are sometimes simply two words with a space between them and sometimes two words separated by their objects.

A simple way to encourage learners to notice or be alert to the possibility of a multi-word verb is to point out that the verbs are:

a) very common

and

b) almost always monosyllabic (of the 62 verbs listed above, only five are disyllabic and none has more than two syllables)

So, if learners encounters a common, monosyllabic verb in a sentence that they are finding difficult to understand, a good bet is that they have encountered a MWV. Time to go to ... - Dictionaries and on-line resources.

The advent of corpus-based linguistics has ushered in a golden age for lexicographers because they now have a way of measuring the frequency of words in real language samples and of noting collocations and other combinations such as multi-word verbs.

While the second part of this endeavour has borne fruit and most up-to-date, general learners' dictionaries are excellent at identifying and explaining multi-word verbs, they still have to take on board considerations of frequency.

Dedicated phrasal-verb dictionaries are also available and are undoubtedly useful reference resources for learners but, in an effort to be inclusive, they try to list almost all the possible phrasal and prepositional verbs in the language and do not, generally, highlight those which are the most frequent and, therefore, the most useful to learn.

One well-known and useful website, for example, claims that it provides "a dictionary of 3,533 current English Phrasal Verbs with definitions and example sentences" (www.usingenglish.com).

The Cambridge Phrasal Verb Dictionary claims to cover "around 6,000 phrasal verbs current in British, American and Australian English".

McGraw-Hill's Essential Phrasal Verbs Dictionary doesn't do quite as well but still claims "1,800 entries with examples of everyday usage".

As references, such books are valuable (especially for those learners obsessed with this area of the language, who are interested in the meaning of, e.g., bring forth, conk out or glom onto) but the acquisition of a working knowledge of the most frequent and useful phrasal and prepositional verbs is not likely to be achieved by using them.

In addition, many of these dictionaries include dubiously categorised expressions such as gallop through the agenda which is not, quite arguably, anything but a verb plus a prepositional phrase.

Handle dictionaries of either sort with some care.

|

Two cautions |

- MWVs, despite what is said above under problems of style, are

very common in spoken communication and it's tempting only to

introduce and practise them that way. Remember, however, that they are

difficult, especially for learners whose languages don't use

them (i.e., the majority) so it makes sense to introduce them

and practise them in writing before asking people to produce

them orally.

Learners need space and time to absorb hard concepts and forms. - Make sure that what you are dealing with actually

is a MWV. We started the analysis in

the guide with the distinction between

Turn down the lane

and

Turn down the offer.

Look carefully at lexemes that come up in a text or in a lesson and ask yourself if it really is a MWV.

She walked across the road

is not an instance of a MWV; it is the verb walk followed by a prepositional phrase telling you where and could be replaced with through the park, down the street, up the hill, over the bridge and many other phrases.

However, in

She walked me through the procedure

we are dealing with a MWV, meaning show or guide, and if we substitute something else we change the meaning of the verb, e.g.:

She walked me over the road / through the park

meaning helped me or accompanied me.

If you don't do this, you will actually be wasting your learners' time getting them to remember walk across as if it were a single lexeme rather than being able to deploy prepositional phrases to say what they mean.

|

Materials |

Almost all coursebooks at appropriate levels will have something (often quite a lot) on MWVs. When assessing the value of materials think about:

- Is the material logically presented?

Does it jumble up different forms and structures – transitive and intransitive, phrasal and prepositional verbs, separable and inseparable verbs and so on? - If it focuses on a verb, does it make the meaning clear?

Does it use the verb to cover many different meanings? - If it focuses on particles, does it do so in a way which

shows a single significance, such as connection or superior

relationship etc. which will help learners to grasp its

essential meaning?

Does it jumble, say, up to mean 'higher' (bring up, hold up, look up to, sit up, set up etc.) with up meaning in its aspectual meaning of 'complete' as in clean up, blow up, cover up, finish up, clear up, lock up and wash up?

If the answer is yes to the second part of each of these three tests, don't use the material or, if you do use it, amend it in a way that makes it usable.

| Related guide: | |

| the first guide to MWVs | for the background analysis |

| for a categorised list of multi-word verbs | |

| polysemy and homonymy | for more on extended meanings, metaphor and figurative uses of language |

| the essential guide to MWVs | for a simpler guide to the area |

References:

Garnier, M and Schmitt, N, 2015,

The PHaVE List: a pedagogical list of phrasal verbs and their

most frequent meaning senses, Language Teaching Research,

19 (6). pp. 645-666. ISSN 1477-0954

The PHaVE list seems to be freely available at

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B7FW2BYaBgeiMkphZXFOM2V2bTA

The PHaVE users' manual is also available at:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B7FW2BYaBgeiMkphZXFOM2V2bTA

Schmitt, N and McCarthy, M, 1997,

Vocabulary - Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press