Prepositions and prepositional phrases

There is

a simpler introduction to prepositions on the initial plus

training pages (new tab). You may like to review that before going on.

If you returning for another look at this guide or are looking for

something in particular, here's an index of its contents.

Clicking on -top- at the end of each section will

bring you back to this menu.

Otherwise, take it as it comes.

|

Definitions |

Prepositions belong to a closed class of words which means

that we do not readily add new ones although some which were quite

common, such as betwixt, afore, athwart etc., fall out of

fashion and are rarely used.

It is, therefore, in theory at least, possible to construct an

exhaustive list of all the prepositions in English. In theory

that is because

- Some prepositions are very rare or archaic and often virtually unknown to the modern user of English such as ahind, alongst, afore etc. which will occur rarely in a restricted set of literary texts.

- Definitions vary slightly and some will include, for example, prefixes such as post-, anti- and pre- which sometimes stand alone as prepositions.

- Some are poetic only, such as ere, o'er, unto, midst etc.

- Dialects of English contain prepositions such as

afront, allow, ayond etc. which are rare or unknown in

many settings.

If you would like a list of prepositions over 200 prepositions in English, follow the link to the PDF document at the end or click here.

For most teaching purposes at lower levels at least, this list is probably enough:

| about above across ago at before below |

beside by for from in into next to |

of off on onto out of over past |

since through till to towards under until |

A prepositional phrase, which is mostly the concern of this

guide consists of the preposition itself (the head) followed by

its complement.

Therefore, a prepositional phrase has two parts:

the preposition and the preposition

complement. Overwhelmingly, in English, the

prepositional head of the phrase precedes the complement (or object

as we shall see) but that is not invariably the case.

|

Task: There are five kinds of prepositional complement. Can you identify them in the following examples? The preposition is in black and the complement is in this colour. Click here for the answers and some other examples when you have tried this. |

- He drives past my house most mornings

- From what you have told me, it is very strange.

- Before opening the letter, he took a deep breath.

- From now to eternity.

- He moved over to under the light.

- a noun phrase complement:

at the station, under my feet, across the Irish Sea, beyond my comprehension, according to him

etc.

When a pronoun is the complement, it is in the object (accusative) case:

Please keep this between you and me

Don't talk to her - a wh-clause

complement:

by what I've heard, from what I assume, about where to go next week

etc.

Sometimes a wh-clause is severely abbreviated (a phenomenon called sluicing) and the wh-word or phrase is left alone as the complement of the preposition as in:

She telephoned but I don't know where from

They arrived but I'm not sure where at

They were afraid of something but didn't say what

In some cases, the preposition itself may be ellipted, too, as in:

John was arguing with someone but I don't know who - an -ing clause

complement:

instead of opening the box, by breaking the window, despite losing his keys

etc.

Arguably, this is sometimes a case simply of a verb acting as a noun and a subset of the examples in point 1. - an adverb or adverb phrase complement:

from here to there, until very recently

etc.

Only adverbs of place and time can function as complements in prepositional phrases and even then there are clear restrictions.

The guide to adverbs, linked in the list of related guides at the end, has more on how certain adverbs co-occur restrictively with certain prepositions. - another prepositional phrase complement:

out from under the car, until after my graduation

etc.

We cannot have a that-clause

or a to-infinitive clause as the complement of a preposition so we

can't say, e.g.

*I understand from that he told me

*He came in by to break open the window

etc.

Other languages do things differently and that accounts for a good

deal of error. Simply telling learners this little fact can be

most helpful.

In all of the above, the examples contain the standard word

ordering of English: preposition followed by the noun phrase.

That is, of course, why the words are labelled

prepositions.

English has, in fact, some postpositions which

perform the same linking function but follow the noun phrase.

See below for examples of their use.

|

Simple and complex prepositions |

Most prepositions are single words like of, in, at, by,

for, with etc. but some, called complex prepositions,

consist of phrases in themselves and they include except

for, with the exception of, in spite of, with reference to,

apart from etc.

A little care is needed to analyse these as complex prepositions

which are followed by a complement rather than conflating part

of the preposition with the complement.

These are not prepositional phrases (although they are phrases)

when they stand alone because the complement is missing.

They are best considered as multi-word prepositions in

themselves.

|

A slightly different way to analyse prepositional phrases |

Some functional approaches to grammar analysis take a slightly different view of the prepositional phrase.

The analysis is that most phrases can be described as an expanded

version of the Head of the phrase.

For example, in this sentence:

The cautious old man spoke slightly hesitantly at the

meeting

the noun phrase, The cautious old man, can be analysed as

the Head (man) being expanded by the pre-modifying

adjectives and the determiner.

In the same way, the verb + adverb phrase, spoke slightly hesitantly,

can be analysed as the Head (the verb spoke) expanded by

the post-modifying adverbs. Strictly, a verb phrase contains

only verb forms, of course, but this matters little here.

However, the prepositional phrase cannot be analysed in exactly the

same way because the phrase at the meeting is not a simple

expansion of the Head (at) but may be better considered as

the preposition plus its object (the meeting).

Calling the complement the object also makes sense in terms of case

because, as we saw above, any pronoun in the complement is in the

object, accusative, case which is why we say:

He walked towards me

not

*He walked towards I.

In this way, prepositional phrases function more like small clauses

than phrases per se.

We do not follow that analysis here, staying with the word complement to refer to the object of the preposition but it is worth explaining, albeit briefly.

An argument against calling the parts which follow a preposition in a phrase objects rather than complements is that they need not always be nominal items although they act that way in terms of grammatical function. A number of other word and phrase-class members can act as the complement of prepositions, as we saw above and they include adverbs, non-finite verb forms, wh-clauses, adjectives (when nominalised), pronouns and other prepositional phrases.

|

Case |

Case refers to the relationship between elements of a clause or

sentence. For example, we saw above that we say:

between you and me

not

*between you and I

because in English all prepositions are followed by the object case

and, for the first-person pronoun in English, that is the pronoun

me.

Similarly, we can have a sentence such as:

She gave me them

in which we have another use of me but this time it is

actually a dative case pronoun because it represents an indirect

object. The word them is the direct object case of

the pronoun they. English does not change the form of

the pronoun me to show whether it is the direct or the

indirect object. That can be done, however, with a

prepositional phrase so we can equally have:

She gave them to me

with the indirect object shifted to the end and preceded by a

preposition.

In other languages, German for example, the pronoun is marked

differently for the object, accusative, case and the dative,

indirect object, case. So for example, in German:

She saw me

translates as

Sie sah mich

and

She gave me it

as

Sie gab es mir

with two pronouns (mich and mir) signalling

the cases (accusative and dative, respectively).

In other languages, life becomes considerably more complicated.

English is not a highly inflected language so does not exhibit

many changes to words to show case. English overwhelmingly

indicates the relationships in syntax by prepositional phrases

rather than changes to the nouns, determiners and adjectives etc.

So, for example:

I hit it with a rock

we have what in some languages would be called an instrumental case

but English makes no change to the rock to indicate this,

preferring to use the preposition with to signal that

the rock was the instrument I used.

We can also have what is called an ablative case as in, e.g.:

She walked away from the station

and English signals this with the complex preposition away from

but other languages (Finnish, Gujurati, Basque and many more,

including Turkish) make changes to the noun to indicate the

relationship between she and the station.

There are many cases which can be signalled in a variety of

languages and for a much fuller run down of the possibilities, see

the guide to case, linked below.

It is enough here to understand that learners whose first languages

have well-developed case structures will, accordingly, have fewer

prepositional structures because the relationships are signalled

via inflexions rather than through the use of function words.

Such languages include:

Czech, Estonian, Finnish, Greek, Hungarian, Polish, Russian,

Serbo-Croat, Slovak, Tamil, Turkish and Ukrainian.

Speakers of those languages will encounter quite serious problems

understanding and using prepositional phrases in English because,

failing a clear case structure, the language has developed a much

more complex system of prepositional structures to signal case

relationships.

Many other languages do not signal case through inflexion and have

ways akin to English to show relationships (or do it via

affixation, often suffixation). These include:

The Chinese languages, Romance languages, Swedish, Dutch,

South-East Asian languages and many African languages.

Despite having parallel systems, naturally, exactly how the

relationships are signalled will not be parallel and difficulties of

choice of the appropriate preposition remain.

We saw above that English has two ways to signal the dative or

indirect object: by word order as in:

She read the children a story

in which the indirect object precedes the direct object, and with a

prepositional phrase as in:

She read a story to the

children

where we use the preposition to to show the indirect

object.

And the language also has two ways of signally the genitive: by

inflexion as in:

It's the company's policy

where we use the 's inflexion, and with a prepositional

phrase as in:

It's the policy of the

company.

using the preposition of.

Most languages settle on one way or another and it is confusing for

learners to have to make such choices when they use English.

|

Blurring at the edges: borderline cases of word class |

Some words can only function as prepositions and present no

serious comprehension or use issues. They include:

against, among, at, bar, barring, beside, despite, during,

except, following, from, including, into, like, minus, of, per,

plus, to, toward(s), upon, via and with.

|

Multiple word-class membership |

Other words with dual or triple class membership can be problematic.

The first group includes most prepositions not in the list above

because simply removing the complement results in an adverbial use.

It may be argued that the ellipsis of the complement leaves the

prepositional nature of the word intact. Compare, for example:

They met outside the pub

which is prepositional and

We can't smoke inside

which is adverbial, with

He was still walking up the mountain while they were

already walking down

where the use of up is prepositional (with its complement /

object the mountain) but in which the use

of down is

either prepositional (with an

implied complement of it or the mountain)

or adverbial (with no

complement).

We have, therefore:

- Words which can function both as prepositions and adverbs,

for example:

- They came aboard (adverb)

They aren't aboard the boat (preposition) - She drove past (adverb)

She drove past my house (preposition)

- They came aboard (adverb)

- Words which can function as prepositions, adverbs or

conjunctions:

- They had met before (adverb)

They spoke before the meeting (preposition)

They spoke before the chairman opened the meeting (conjunction) - I haven't seen him since (adverb)

She has waited since the summer (preposition)

I'll tell you, since you ask (conjunction)

- They had met before (adverb)

- Words which can function as prepositions or conjunctions:

- I bought it for $400 (preposition)

You can't speak yet for questions are only allowed at the end (conjunction) - She dressed as Cleopatra (preposition)

She asked as she needed to know the answer (conjunction) - She smiled like a

cat (preposition)

They did it like they were told (conjunction)

- I bought it for $400 (preposition)

- A few words which span other word classes:

- He walked through the park (preposition)

I'm not through yet (adjective) - The opposite meaning (adjective)

Leave it on the opposite side (adjective)

I placed it opposite the mirror (preposition) - It was an inside job (adjective)

I left it inside (adverb)

The inside is painted red (noun)

It's inside the house (preposition) - She came to a like

conclusion (adjective)

There was a fish-like smell in the house (adverb or adjective-forming suffix)

We put like with like (noun)

It looked just like it did in the brochure (conjunction)

I had a house like the one over there (preposition)

I like that (verb) - She walked out

into the garden (adverb, followed by a prepositional

phrase)

That's right out in the country (modified adverb followed by a prepositional phrase)

They walked out the door (preposition [informal])

There's no answer so I guess she's out (adjective, [predicative only])

The truth came out later (adverb)

The truth was out (adjective)

We need an out (informal noun)

It's snowing out (adverb, for outside)

The candidate was outed as a liar (verb)

- He walked through the park (preposition)

|

Borderline cases |

Some words lie on the borderline between prepositions proper and conjunctions, adjectives or adverbs and in these cases, the distinctions can become blurred.

- in that

- looks like a preposition phrase and, what's more, like an

exception because we have in followed by a that-clause

as in, for example:

She has an advantage, in that she speaks both languages

It is, in fact, a rather unusual conjunction meaning because or for the following reason and is better analysed that way. - but / bar

- but is usually analysed as a conjunction and that is

its function in, for example:

I called but you were out

However, the word also has prepositional characteristics and can be followed by an infinitive as in, for example:

He did nothing but work

and it can be followed by a noun phrase or pronoun quite normally as a preposition in, for example:

Everyone came but the Smiths

Nobody wants to go but her

We saw above that prepositions are followed by pronouns in the object case and here the distinction becomes even more blurred because

Nobody but her knew the truth

is acceptable and prepositional although

Nobody but she knew the truth

is also acceptable but not prepositional because the pronoun is in the subject case. Compare:

Nobody knew the truth but she did

The preposition bar follows the same patterns and also means except for as in, for example:

It's all over bar the shouting

All the people bar Mike and John were satisfied - than

- functions as a conjunction in, for example:

He spends more than he can afford

It's more expensive than I hoped

but can also be prepositional as in, for example:

She is taller than me

It's more than 5 miles from here

The prepositional use allows an infinitive complement, with and without to as in, for example:

It is better to call by than to 'phone

I'd prefer to stay than go - except

- also functions as a conjunction in for example:

I wanted to come except I had no money

It doesn't hurt except when I'm very tired

in which case it means roughly but, and in common with but can also be used prepositionally in, for example:

Everyone one came except Julian

and, like but, can be followed by an infinitive

She does little except sleep - as well (as)

- is an adverb (an additive adverbial adjunct to be precise)

in many circumstances as in, for example:

It snowed a little and rained as well

and can also function as what is sometimes called a quasi-coordinating conjunction in, for example:

He writes novels as well as contributing to the newspaper

but the phrase is also prepositional in, for example:

I'll paint the door as well as the window frames - because

- is a subordinating conjunction as in:

He came home because it was raining

but combined with of it is a complex preposition as in:

He came home because of the rain - instead

- is an adverb conjunct in for example:

I don't want to go swimming. Instead, I'll stay in and read.

but combined with of, the word is a preposition as in

I'll have the fish instead of the meat course - near

- is, of course, a preposition in something like:

The library is near the cinema

but it has adjectival characteristics, too, because it can be made comparative and superlative as in:

The pub is nearer your house than mine

The house nearest the cinema is hers

and can also be used predicatively and attributively as adjectives usually can as in:

You place is nearer

The nearest pub is just over there

The prepositions close and like share some of these characteristics. - worth

- this word is a predicative-only adjective but it governs the

noun in a preposition-like fashion in, e.g.:

It is (well) worth visiting the museum

It is not worth my time

It's not worth $400

|

|

British (BrE) and American (AmE) usage |

There are some differences between British and American usage in this area. Here's the summary:

- at vs. on the weekend

- AmE speakers prefer on the weekend, BrE speakers prefer at the weekend

- from ... to / until vs. through

- to express the beginning and end of a period of time, AmE

speakers prefer through as in, e.g.:

The shop is open Monday through Saturday

but BrE speakers prefer either from ... to or from ...until / till as in:

The shop is open from Monday to Saturday

The shop is open from Monday until Saturday - in vs. for ages

- After a negative, AmE speakers prefer in + the time

period:

I haven't seen the movie in years

BrE speakers prefer for + the time period:

I haven't see the film for years - in vs. on the street

- AmE users prefer on:

They live on Washington Street

BrE users prefer in:

They live in Nelson Street - out and out of

- Both varieties use out informally as a preposition

rather than out of but AmE also more frequently uses

out adverbially as a synonym for outside:

AmE will usually prefer:

He threw it out the window

It's raining out

BrE will usually prefer:

He threw it out of the window

It's raining outside

|

Ellipting prepositions |

Usually prepositions are required because they form the head of the prepositional phrase, without which it is not possible to understand what is meant. However, there are some verbs whose meaning incorporates the meaning of the preposition. In these cases, we can ellipt the preposition and make the erstwhile complement the direct object of the verb. Like this:

| He ran in the race | → | He ran the race |

| The horse jumped / leapt over the fence | → | The horse jumped / leapt the fence |

| She fled from the party | → | She fled the party |

| They drilled through the wall | → | They drilled the wall |

| They climbed up the hill | → | The climbed the hill |

| Mary hopped over the wall | → | Mary hopped the wall |

| I joined in the game | → | I joined the game |

| I rowed across the river | → | I rowed the river |

| She penetrated into the secret room | → | She penetrated the secret room |

| The wind pierced through his jacket | → | The wind pierced his jacket |

| We have turned round a corner | → | We have turned a corner |

Many languages do not allow the ellipsis of a preposition in

this way and learners may have some difficulty comprehending

clauses like the ones on the right.

Other languages may allow the ellipsis of an understood

preposition but allow verbs to be transitive which are, in

English, stubbornly intransitive or demand a preposition at all

times when they are transitive. This results in errors

such as:

She arrived the hotel

They participated the meeting

It consists two parts

That depends the weather

etc.

We saw above that in sluiced wh-clauses, the preposition

and the whole complement other than the wh-word may be

ellipted as in:

She was speaking to someone outside but I

don't know who

|

Prepositions are always followed by their complements – right? |

Click here when you have an answer.

Wrong. There are a number of times when they are preceded by their complements (or when, in fact, there is no complement). Here are the main ones:

- wh-questions

- There's a question of formality here. For example:

Where did you leave from?

vs.

From where did you leave?

Many consider the second of these to be overly formal. - Relative pronoun clauses

- There's also a style issue here. For example:

That's the man who(m) I was talking about

vs.

That's the man about whom I was talking

Again, many consider the second of these to be overly formal. - Passives

- For example:

She was looked for by her grandmother. - Infinitive clauses

- For example

She's impossible to talk to.

We have already noted that English has some postpositions, including, ago, apart, aside, which follow rather than precede their complements. A section below explains their use.

|

What do prepositional phrases do? |

Here are 8 example sentences. Decide what each

prepositional phrase is doing and then click on the

![]() for some comments.

for some comments.

|

She was walking

through the park |

Here the prepositional phrase is an adjunct (i.e., it's

an adverbial which is integral to the clause). It

is probably the most common prepositional use.

|

|

She arrived

after six o'clock |

Here the prepositional phrase is also an adjunct.

It differs from the first example because that refers to

space and this one refers to time.

|

|

To her

astonishment, the shop replaced

the shoes immediately |

Here the prepositional phrase is a disjunct (i.e., it

refers to the whole clause which follows, not just the

verb phrase, and is not

integral to the clause itself).

|

|

In addition,

I'd like to ask for a small pay

rise |

Here the prepositional phrase is a conjunct, linking the

previous sentence with this one.

|

|

The man

in the garden

is his father-in-law |

This is sometimes called a reduced relative clause

(i.e., reduced from The man who is in the garden)

but,

in fact, it can more simply be seen as a post-modifier

of the noun man.

|

|

It all depends

on the weather |

The verb here is a prepositional verb (depend on) and the

prepositional phrase is its complement. In such

cases, the preposition is governed by the verb rather

than by its noun complement (or object).

|

|

I am angry

at your suggestion |

Here the prepositional phrase is the complement of an

adjective.

The guide to adjectives, linked at the end, contains more detail. |

|

I cleaned

under the car |

Here the prepositional phrase is the object of the verb

clean and is nominalised.

|

|

Behind the garage

needs clearing |

Here the prepositional phrase is the subject of the verb

need and is also nominalised.

|

Reference to things like adjuncts, conjuncts and disjuncts in the following may be ignored if they make no sense to you. For more in the area, see the guide to adverbials.

|

Prepositional phrases as adjuncts |

It is often averred that prepositions in English are wholly

unpredictable and obscure. While it is true that it is

difficult to say what all prepositions 'mean', there are some useful

patterns we can use to teach the area.

Can you classify these? As before, click on the

![]() for an answer.

for an answer.

|

Because of the

rain, we stayed in For fear of the consequences, he told nobody On account of the difficulty, he decided not to bother |

All these contain the notion of reason or motive.

Note that of is the most common preposition in

the phrase although out of (in, e.g.,

out of

a sense of

justice) is a possible but rarer form.

|

|

He only works for the money They all ran for the ball at the same time She did it for the good of the village They queued for a bus He took the train to London He gave it to me |

Prepositional phrases with

for often express

the notions of purpose or

destination. If you can

rephrase the sentence using in order to plus a

verb, then

the preposition is usually for.

Prepositional phrases with to express a similar notion but here it is either the target or the recipient. Target may also be signalled by at as in, e.g., He threw it at me. Note the difference between at (a target) and to (a recipient) in: He threw the ball at me / Screamed at me He threw the ball to me / Screamed to me |

| She

shouted with great passion She spoke like a teacher He worked in an orderly way |

Prepositional phrases with

with, like and

in

(nearly always + adjective + manner or way)

express the notion of in the manner of.

Note the difference between like (in the manner of) and as (in the role of) in, e.g., She dressed as Marie Antoinette for the party vs. She dressed like Marie Antoinette.) |

| We went

by tram He left by the back door They came by car |

Prepositional phrases which express means

nearly always contain by.

Such phrases are not always used for transport but that

is frequent and a helpful conceptual tag (providing you

don't get too involved in the irregular

on foot).

The by + participle form, e.g., By breaking the lock, he managed to escape is common to describe means. |

| She opened

her talk with an anecdote They broke the door down with an axe He wrote with a special pen |

Prepositional phrases which express the

instrument rather than the means nearly always

contain with. It

is important to distinguish this and the last category

as confusion is often the source of errors such as

*They came with

the

bus, *He wrote by

a

pencil.

Both by and with can be the agent of a passive but that with is usually confined to inanimate objects. For example, The fire was put out by the neighbours vs. The fire was put out with water. It is possible, and quite common, to combine by and with in the same clause: He broke the lock by hitting it with an axe. Note, too, that by is sometimes replaced by at in the passive sense: She was astonished at / by his rudeness. |

| He came from

London She spoke from the audience etc. |

The converse of phrases with

to and for is often a phrase

with from

denoting source or origin.

|

| He came

at six She spoke before thinking etc. |

These are simple prepositional phrases of time, aka, temporal

prepositional phrases and a common familiar use of the

items.

|

| He put

the case in the corner She sat at the top table etc. |

These are examples of spatial uses also called place

phrases.

|

|

Prepositional phrases as disjuncts |

|

and conjuncts |

|

In spite of the

rain, we went out Despite the consequences, he carried on Notwithstanding the difficulty, he decided to do it |

The most common of these is, of course,

in spite of but

the other two mean the same although they are more

formal. They all carry the notion of

concession. (Conjunctions like

although can be used in a

similar way but these examples are prepositional

phrases, not conjunctions.)

|

|

With regard to the money,

a refund is due As for the children, they are happy in the sunshine With reference to your letter, I am writing to explain Regarding your question, the manager will respond |

There are various levels of formality here but the

notion is the same for all – reference

to something. These examples are disjuncts (hence

the separating commas) but

they can be used to post-modify in, e.g.,

What answer did you get regarding your question? |

| It's all

over bar the shouting Everyone is here except the teacher Everyone but the teacher is here Except for the teacher, everyone is here Apart from the teacher, everyone is here But for the teacher, I couldn't have learned it |

These all carry the notion of exception.

Prepositional phrases with bar, except and but are post-modifiers here. Except for and apart from are both disjuncts. The other examples here are actually adjuncts. Notice that but for is slightly different. It carries the notion of conditionality (If it hadn't been for ...) Notice, too, that but is not a conjunction in this use. |

|

To my amazement, he agreed To her horror, the road was blocked To their joy, the boss conceded |

To introduces

many expressions of reaction.

These are all attitudinal or content disjuncts and are often more formal ways of saying, e.g., amazingly, horrifyingly, happily etc. |

|

Prepositional phrases as noun post-modifiers |

This is another large category but, in fact, only three prepositions are common in these phrases. They all express the notion of having an attribute. Some examples:

- The woman with red hair

- A man of honour

- A girl without humour

- A complaint about the food

- His success in passing the examination

Prepositional phrases with without

and with are frequently a form of relative clause.

Compare

A man with a grudge

with

A man who has a grudge

or

A woman

without any money

and

A

woman who has no money.

You can't do that with phrases with of

(and they are less common). The

of-phrases are normally only used with abstract

properties so we can have

A woman of great determination

but not

*A woman of beautiful hands

etc.

Many other types of prepositional phrases can act as post-modifiers, often stating where or when something is. For example:

- The house on the corner

- The meeting on Monday

- The girl in the queue

There are some prepositions which appear to be verbs because they

end in -ing, but aren't. They include:

concerning, considering, excepting, excluding, failing,

following, including, notwithstanding, pending, regarding,

respecting and saving.

They are troublesome because they occur in constructions which look

like reduced relative clauses but for which there is no

corresponding -ing form in the relative clause or for which

no relative clause at all can be constructed with a parallel

meaning.

For example:

- He wrote a letter concerning his complaint

which cannot be rephrased as

*He wrote a letter which was concerning his complaint - Everyone arrived excepting only the Jones family

We will wait pending your answer

He responded following the same format

for none of which can a corresponding relative clause be constructed.

The confusion arises because formulations using non-finite clauses to post-modify the noun such as

- A car resembling hers

- A tie matching his shirt

- A meal consisting of beans and potatoes

etc.

can all be rephrased as relative clauses although the -ing form of these verbs is not always available because the use is stative not dynamic:

- A car which resembled hers

- A tie which matches his shirt

- A meal which consists of beans and potatoes

For more, see the links at the end.

|

Constituents of phrases |

We need to be slightly careful in deciding what exactly a

prepositional phrase is modifying or our hearers can misinterpret

what we mean.

For example, the sentence:

Jane spoke to the man behind the bar

can be understood in two ways, like this:

In the first sentence, the verb is being

post-modified and tells us where she spoke so the modified verb

phrase is:

spoke ... behind the bar

In the second sentence, the noun is being

post-modified and the object noun phrase is:

the man behind the bar

When the first sense is intended, speakers will insert a slight

pause between the man and behind the bar, making

two tone units each with a stressed syllable: the

man and behind the bar.

When the second sense is intended, the man behind the

bar will constitute a single tone unit

with one stressed syllable. (For more, see

the links at the end.)

In writing, to avoid ambiguity the sentence may be rephrased as a

cleft:

It was behind the bar that Jane spoke to the

man

or

It was the man behind the bar that Jane spoke

to

or the prepositional phrase is moved to make the arrangement of

phrases clear:

Behind the bar Jane spoke to the man.

|

Prepositional phrases as subjects and objects of verbs or copula complements |

| under the stairs is a good place |

Prepositional phrases may act in place of a noun phrase to

perform various syntactical roles. In these cases, the

phrase is itself nominalised. Such uses are often

considered quite informal and some will reject them as

ill-formed clauses.

We find, however:

- Prepositional phrase as the subject of the verb

- For example in:

In the garden is the best place for that

Behind that door needs painting

the prepositional phrases are the subjects of the verbs. - Prepositional phrase as the direct object of the verb

- For example, in:

I should clean behind the fridge

We need to heat in the study

We should be slightly careful here, because often the phrase is being used in a normal location function so, for example:

She remained in her bed

is not a case of a nominalised prepositional phrase because the verb is intransitive and takes no object and:

She wrote in the study

is also just a potentially transitive verb being used intransitively with the prepositional phrase acting as a simple adverbial adjunct. The object of that verb has to be something like the letter of course.

The simplest way to check is to form the passive and then we see that we can have:

Behind the fridge was cleaned

but no such passive clause can be constructed from

She wrote in the study. - Prepositional phrases as complements of copular verbs

- For example, in:

She seemed at home

The were in the house

They appeared under pressure

and so on, the prepositional phrase is acting as the subject complement of the verbs seem, be and appear, respectively.

They can also, more rarely, form object complements of quasi-copular verbs as in:

She appointed him to the job.

|

Prepositional phrases as verb and adjective complements |

| made of wool |

Prepositional phrases can appear as the complements of verbs and adjectives. For example:

- Complementing the verb:

The table is made of mahogany

We argued about the cost - Complementing the adjective:

I am lousy at sports

She is reliant on your help

Some verbs are described as having dependent prepositions or as being prepositional verbs (much the same thing) and they are analysed more thoroughly in the guide to multi-word verbs, linked below.

Adjectives and nouns requiring adverbial complementation

- Some adjectives, such as tantamount, dependent, and reliant require a prepositional

phrase complement. So, for example, we cannot have:

*It is tantamount

*She is dependent

*It is reliant

and we need a prepositional-phrase complement for each adjective and that might be:

... to a resignation

... on her parents

... on the weather

There is more on this in the guide to adjectives, linked below. - Some verbs, notably:

keep, lay, place, plonk, position, put, rest, set, site, situate, stay, stick, stuff

also require adverbial complementation (often a prepositional phrase) when they are used. So, for example, we cannot allow:

*I put it

*I rested the torch

*She stuck the suitcase

without saying where and that often means using a prepositional phrase (or an adverb such as outside) to form an acceptable clause with, e.g.:

... under the stairs

... on the work surface

... under the bed

For obvious reasons, such verbs are often referred to as PP verbs.

|

Patterns of meaning |

Because adjectives and nouns are often formed from verbs, it is useful to address these three types of complementation together. There are similarities concerning which preposition will be used as a complement and that is helpful to learners.

Here's a table of what is meant but you can see that some cells have no contents bar participles in -ing because no other obvious adjective parallel is available.

| Preposition | Verb | Adjective | Noun | Preposition | Verb | Adjective | Noun | |

| about | argue ask care complain enquire hang quarrel row talk |

argumentative curious careful quarrelsome |

argument enquiry quarrel row talk |

of | approve conceive consist suspect talk |

approving suspicious |

approval concept suspicion |

|

| at | connive laugh |

Participles in -ing only | connivance laughter |

on | bear comment concentrate count decide depend insist plan rely |

dependent insistent reliant |

commentary concentration decision dependency insistence reliance |

|

| for | account ask long vouch vote wish |

accountable asked longed wished |

accountability request longing vote wish |

to | admit amount conform object stick react |

admissible conformable objectionable adherent reactive |

admission conformity objection reaction |

|

| from | abstain suffer refrain |

Participles in -ing only | abstention pain |

with | acquaint agree coincide collide comply conform confuse deal |

agreeable coincidental compliable conformable confusable |

acquaintance agreement coincidence collision compliance conformity confusion |

|

| in | participate succeed |

participatory successful unsuccessful |

participation success |

In the guide to multi-word verbs, a distinction is drawn between transitive uses, which usually take the prepositional phrase, and intransitive uses, when the preposition is omitted.

Unfortunately, there are few rules or even recognisable

tendencies which can help learner decide which preposition is

appropriate in each case so the expressions are most usefully

treated as language chunks and learnt as single lexemes.

However:

- about and on frequently refer to subject matter (so one can have a talk about and a talk on a subject).

- of / out of, from and with frequently refer to ingredients or materials (cooked with, made out / out of, made from, constructed from, manufactured with etc.

- at is frequently found in connection with ability (good at, bad at etc.)

- from often implies protection (secure from, sheltered from, shield from, screen from etc.)

- with frequently collocates with emotions (angry with, unhappy with, delighted with, impatient with etc.) and can often be replaced with by referring to the agent in passive constructions (angered by, delighted by, annoyed by etc.)

Many adjectives do not appear in the table above because they

are not derived from verbs. They do, however, often have

derived nouns or are themselves derived from nouns which take

the same prepositional complements. (This is not a fully

reliable rule because there are rogues such as be fond

of vs. have a fondness for

which do not conform.)

The guide to adjectives, linked below, lists nine

prepositions which are commonly used in the complementation of

adjectives. Briefly, these are:

| Preposition | Adjective | Noun | Preposition | Adjective | Noun | |

| about | glad,

knowledgeable, mad, annoyed, pleased, angry, happy etc., e.g.: I was happy about the news |

happiness, knowledge, annoyance etc., e.g.: His knowledge about the subject is immense |

of | accused, afraid, certain,

conscious, aware, glad, scared, terrified, fond, tired etc.,

e.g.: I am afraid of snakes |

fear, accusation, certainty, awareness, terror etc., e.g.: The accusation of fraud was proven |

|

| at | alarmed,

amused, terrible, awful, hopeless, surprised, dreadful, clever, good

etc., e.g.: He's clever at twisting the argument |

alarm, amusement, terror, surprise etc.,

e.g.: His amusement at my embarrassment was obvious |

on | intent,

severe, based, set, dependent, reliant, keen etc., e.g.: We are reliant on the money |

dependency, reliance, keenness etc., e.g.: Her reliance on my help was mistaken |

|

| The preposition upon is more formal in many circumstances and not possible for some adjectives (such as keen). Using on is always secure. | ||||||

| for | embarrassed,

bad, hopeful, optimistic, renowned,

sorry, known, responsible etc., e.g.: The town is known for its crime These uses include the notion of something being unusual as in, e.g.: It's small for an estate car That's not bad for a man etc. |

embarrassment, hope, optimism, sorrow, responsibility etc.,

e.g.: Your responsibility is for the whole project |

to | opposed,

averse, subject, liable, answerable, inclined etc., e.g.: He is liable to a fine |

opposition, aversion, liability, inclination etc., e.g.: My aversion to flying means I can't go |

|

| from | These are often participle adjectives and include: secured, defended, kept, exhausted,

sheltered, protected, different, (in)distinguishable, tired

etc., e.g.: She is indistinguishable from her sister |

security, defence, shelter, protection etc., e.g.: The plants need protection from the wind |

with | angry, busy, comfortable, compatible, impatient, familiar,

content, furious, identical, sick, uneasy, unhappy, annoyed, bored,

delighted, obsessed, pleased, satisfied etc., e.g.: This is not compatible with the policy |

anger, compatibility, impatience, uneasiness, annoyance, delight

etc., e.g.: Her impatience with delay was legendary |

|

| in | experienced, justified, persistent, (un)successful,

interested, mistaken etc., e.g.: They were successful in their examinations |

experience, justification, persistence, success, interest

etc., e.g.: Your interest in grammar is obvious |

||||

If you would like to have those two tables as a PDF document, use the link at the end.

|

Modifying prepositional phrases |

Prepositional phrases can themselves be modified with adverbial

phrases. The modification always precedes the phrase.

Prepositional phrases of time and place are most commonly (i.e.,

not solely) the ones we can modify.

The modifiers are adverbials (and nearly always simple adverbs) and serve to amplify or tone down the

phrase. They are, in other words, intensifiers.

Some are colloquial (almost slang) while others, such as

directly are neutral in style.

For example:

- His explanation went completely over my head

- His house is far off the road

- They came dead on time

- They were very nearly on time

- The bullet went clean / clear through the window

- It's directly / almost / exactly opposite the station

- It's right out in the country

- The meeting started shortly after 6 o'clock

- The film started long after the advertised time

- They didn't arrive until way after midnight

- The man spoke purely / solely / only / just / exclusively / merely in his own interests

- That's a comment very much out of order here

- The came well before time

- We looked all over the town for a replacement

- My house is right behind the school

- It was smack dab in the middle of the garden

- She hit him slap bang in the middle of his body

- His shop was bang slap in the centre of the town

- He planted the seeds wide apart from the others

- That's wide of the mark

The last example is a fixed idiom with wide

deriving from archery. In this case, it is adjectival rather

than adverbial but behaves a little like a prepositional phrase in

itself. Compare, e.g.:

His estimate was wide of the real cost

The actual quantity was wide of the amount we wanted

Semantically, there are some limitations with these modifiers as some, such as completely cannot be used for place but are reserved for direction. Here's a run-down of what is allowed:

| Phrase type | Modifiers | Examples |

| Direction / Movement | completely clean / clear |

over the top through the glass |

| Position (central) | slap bang bang slap smack dab |

in the centre in the middle on top of under |

| Position | far almost directly way all well right out |

away from the truth next to the house opposite the pub beyond the end of the road along the river to the left in the suburbs |

| Time | dead shortly long way well |

on time before the beginning after the end behind the times beyond midnight |

| All types | (very)

nearly right almost |

opposite the church after six o'clock in the road |

Some of the examples, such as far away from the truth, over the top and behind the times are or can be metaphorical in nature but that does not affect the main issues.

Limiters such as purely, solely, only, just,

exclusively, merely can modify many abstract

prepositional phrases. For example:

She may leave only

after the end of the

examination time

This door is exclusively

for members of the club

This is merely for

example

They cannot modify time and place phrases so we do not find:

*That is merely in the middle

*They came solely at 6

etc.

Standing alone, very does not modify prepositional

phrases in English (although an equivalent word sometimes does

in other languages) so we do not allow, e.g.:

*He was very at the top

etc.

However, in combination with nearly, which itself can

modify almost any prepositional phrase, the adverb is frequently

an additional modifier so we can allow, e.g.:

He was (very) nearly

at the top

My house is (very) nearly

opposite the church

They arrived (very) nearly

at seven

When very is the only modifier, it is not modifying the

prepositional phrase but an adjective or adverb in the normal

way, for example:

The house is very close to the park

He walked very far from the village

The adverb almost has two functions. It can

stand alone as a prepositional phrase modifier with few

restrictions so we get:

It is almost

at the end

Almost opposite

the church is a cinema

He waited until almost

at the end of the week

etc.

and it can tone down the sense of another modifier as in, e.g.:

She stood almost directly

on the edge of the cliff

She hit the target almost exactly

in the middle

The lorry crashed almost clean

through the wall

There is a slightly grey area here.

Prepositional phrases are, as we see above, normally only

pre-modified. However, in sentences such as:

The science of black holes is over

my head entirely.

it appears that the prepositional phrase over my head is being

post-modified by the intensifying adverb entirely.

The argument here is that it isn't only the prepositional phrase

that is being modified but the whole preceding clause that is being

modified by the adverb (entirely is, in other words, a disjunct or

sentence adverbial).

The same consideration applies to, for example:

Wholly, in

my opinion, this is the wrong

way to proceed.

|

The position of prepositional phrases |

Syntactically, where prepositional phrases come in a clause

depends to a large extent on the function they are performing.

They can come at the beginning, in the middle or at the end (called

initial, medial and final positions in the trade).

Here's how it usually works:

- Prepositional phrases modifying nouns

- These normally post-modify and follow the noun phrase

immediately as in, for example:

The man in the corner

The cars on the road

The bus at ten past six - When there are two or more noun phrases, the

prepositional phrases modify them in the same way, i.e., the

phrase modifies the immediately preceding noun.

This means that people will understand them that way so, for

example:

The man walking the dog with red hair

means the dog had red hair but

The man with red hair walking the dog

means the man had red hair. - The position of the prepositional phrase can lead, as we

saw, to ambiguity. For example:

He used the computer at his office

can mean either

While he was in his office, he used the computer

or

He used the computer which was in his office

Because the prepositional phrase so strictly follows the noun phrase, the normally interpretation will be the second one.

- These normally post-modify and follow the noun phrase

immediately as in, for example:

- Prepositional phrases as adverbial adjuncts

- When the phrase is modifying the verb and integral to

the clause, it usually comes immediately after the verb

phrase or its object. That is its commonly unmarked (i.e., having no

special emphasis) position. Like this:

She saw him on Saturday at the hotel

They met outside the cinema on Monday - To deal with the possible ambiguity issue, the

prepositional phrase is often moved to the initial or final

position as we saw above. Compare, for example:

His friends at that time were working

which could be a phrase modifying the friends (i.e., they were friends then but not now) or an adjunct modifying the verb phrase were working (i.e., telling us when they were working)

with

At that time, his friends were working

or

His friends were working at that time

both of which can only be interpreted as prepositional phrases modifying the verb (i.e., adverbial adjuncts) and refer to the time the friends were working. - When they are marked in some way, however, the phrase is

often elevated to the initial position. This is common in

written English because the phrase cannot be marked by

stress or intonation as it can in spoken texts, so word

ordering is the only option. In writing, the phrase is

separated from the rest of the clause by a comma and in

speaking, by a slight pause after the phrase.

E.g.:

At the hotel, she saw him (i.e., nowhere else)

On Monday, they met (i.e., not on any other day) - When the prepositional phrase is an adjunct very

closely connected to the verb as in, e.g., a verb of

movement and its destination or a prepositional verb, the

prepositional phrase is rarely moved to the initial

position unless some heavily marked meaning is intended:

Mary marked the house on the map

On the map Mary marked the house

They jumped over the wall

Over the wall they jumped - Placing a comma or a pause in spoken language, after the

prepositional phrase produces a slightly different meaning:

Over the wall they jumped

emphasises what was jumped over

Over the wall, they jumped

means that they were already over the wall and then jumped. - The medial position is also possible for adverbial

adjunct prepositional phrases but there is a need to be

careful to avoid ambiguity and the phrases usually have to

be separated by commas or pauses in speaking. For example:

- After the subject:

Dave, at the moment, is too busy to do it - After the verb phrase and its complement:

Dave is too busy, at the moment, to do it - After the auxiliary verb or operator

Dave is, at the moment, too busy to do it - Between the object and its complement:

Dave did it, on the whole, rather badly - Finally:

Dave is too busy to do it at the moment

- After the subject:

- When the phrase is modifying the verb and integral to

the clause, it usually comes immediately after the verb

phrase or its object. That is its commonly unmarked (i.e., having no

special emphasis) position. Like this:

- Prepositional phrases as conjuncts

Because the function of a conjunct is to provide a connection between clauses, the preferred position is the initial one for the second clause or sentence. We get, for example:

He refused to come with us. Without him, we had a lot more fun

The last pair played very well. But for that, we would have lost the match - Prepositional phrases as disjuncts

Disjunct prepositional phrases, expressing the speaker / writer's attitude or a viewpoint, normally come in the initial position but can take the final position. For example:

To my disappointment, the weather turned cold and wet

The weather turned cold and wet, to my disappointment

From my point of view, that's a poor idea

That's a poor idea, from my point of view

In the study of language, the word 'register' is used in a special sense

The word 'register' is used in a special sense, in the study of language - Multiple prepositional phrases

- When a clause contains more than one adverbial adjunct prepositional

phrase, they are usually ordered in relation to how closely

connected they are to the verb phrase and its object. So, for

example, we get:

She spoke to him in French after dinner

rather than

She spoke to him after dinner in French

because the language she spoke in is more closely connected to the verb than the time she did the speaking, or

He walked across the park in the rain

rather than

He walked in the rain across the park

because where he walked is more closely connected to the verb than the weather conditions. - An alternative positioning is to use one prepositional

phrase initially and keep the most closely connected

phrase in the final position following the verb phrase and

its object, if any, as

in:

After dinner, she spoke to him in French

or

In the rain, he walked across the park - When it is unclear which prepositional phrase is more

closely connected to the verb phrase, either ordering is

allowable so we get:

She met him at the pub on Thursday

She met him on Thursday at the pub

with very little if any change in emphasis and none in meaning.

- When a clause contains more than one adverbial adjunct prepositional

phrase, they are usually ordered in relation to how closely

connected they are to the verb phrase and its object. So, for

example, we get:

|

A note on prepositional time phrases |

The general rule is that we use:

- in for large time units (in March, in winter, in 2001, in the second decade / week, in the 19th century etc.)

- on for the next size down

(on Monday,

on my birthday etc.)

(Quite logically, incidentally, AmE has on the weekend but BrE sticks with the illogical at the weekend.) - at for more precise times (at 16:15, at 9 etc.)

There are

exceptions, notably at

night (reserving in

for other parts of the day) and at

the weekend.

However, if we use referencing (i.e., deictic) words like

next,

last, this, after next, before last etc., we can drop the

preposition. We get, therefore, for example

I'm seeing her (the) Monday after next

We met (the) January before last

I'll come next week

I saw him last Thursday

We married that month / year etc.

We also do this when we quantify the noun in some way: e.g.

I take some Mondays off

I work every afternoon

I have a meeting most weeks etc.

Informally, we can also drop the preposition on days of the week: e.g., I'll see you Monday.

|

Postpositions in English |

English, prefers prepositions inasmuch as the head of a phrase is

followed by its complement rather than preceded by it. That is

why they are called prepositions,

of course.

English does, in fact, have some obvious postpositions which follow rather

than precede the noun. The common five are:

- ago

This is sometimes referred to as an adverb but its nature is prepositional because it relates to a noun phrase of time not a verb. We get therefore, for example:

He left two hours ago

not

*He left ago two hours - apart

This, too, is often an adverb as in, e.g.:

They remained apart

or it can be part of a complex preposition as in

Apart from the long flights I enjoyed my trip to the States

but it, too, can be a postposition with the same meaning as in, e.g.:

The long flights apart, I enjoyed my trip to the States - aside

This is often an adverb as in, e.g.:

Please stand aside

or can occur as part of a complex preposition as in:

This is a good hotel aside from the poor food

but it can be used as a postposition to mean apart from (which is prepositional in English) in, e.g.:

The argument with the host aside, I enjoyed the party - away

This is postpositional when it is not an adverb:

She lives five miles away - notwithstanding

This word is normally used as a preposition as in, for example:

I shall take a walk notwithstanding the rain

but occurs as a postposition in:

I shall take a walk, the rain notwithstanding

There are six more rarer or idiomatic examples:

- The word hence is often used

postpositionally as in:

That day hence, he saw her no more

but is literary and very formal. - The preposition on (and the

phrase from then on) are used postpositionally in

the sense of hence as in:

She worked from nightfall on

but it is, again slightly stiff and formal although:

They got married ten years on

does not seem overly formal. - The word through

appears idiomatically as a postposition in expressions with

the whole + a period of time such as

He worked the whole night through

We enjoyed ourselves the whole day through - The word over is a

postposition in a phrase such as:

This is the same the whole world over - The now archaic and rare word withal meaning

with when it is a postposition occurs, better,

occurred, as

in, e.g.:

She lived her family withal

It is only very slightly more common when it is used as an adverb (meaning something like moreover). - The word short is

postpositional in, e.g.:

We are six hundred pounds short

There are a few, quite limited, examples of what appear to be postpositions

in English.

These kinds of expressions are usually better analysed as either adverbs as in:

from that day on(wards)

this time around

or as

ellipted complements as in:

the church opposite

(me, you, us, my house etc.)

|

Other languages: adpositions |

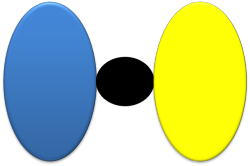

No analysis for teaching purposes like this one would be complete without some consideration of how other languages address the issue of saying where and when an event took place or a state existed. The term to use here is adposition rather than speaking loosely of prepositions as we shall discover.

Overwhelmingly, however, English opts for prepositions and many

other languages take the same ordering.

In English we have a phrase such as

on

the table. This will translate into a variety of

languages in the same ordering so we have, e.g.:

| Swedish: | på bordet | French: | sur la table | German: | auf dem Tisch |

| Spanish: | en la mesa | Bulgarian: | на масата | Greek: | πάνω στο τραπέζι |

| Polish: | na stole | Russian: | на столе | Swahili: | juu ya meza |

| Scots Gaelic: | air a 'bhòrd | Albanian: | mbi tavolinë | Igbo: | ke okpokoro |

and so on. In all these languages, and hundreds more, the

adpositional phrase is left headed. That is to say that the

head of the phrase, what we can call in English and these languages

the preposition, lies to the left.

Most South-East Asian languages, such as Thai, Lao, Vietnamese and

Khmer are also left headed.

That is not the only way to order the elements and many languages

are right headed (or head final) so the adposition lies to the right with the noun

phrase complement or object preceding it. They are

postpositions, in other words, like the English ago.

For example:

| Basque: | mahai gainean | Turkish: | masanın üstünde | Somali: | miiska dushiisa |

| Estonian: | laua peal | Japanese: | テーブルの上に | Finnish: | pöydällä |

| Kasakh: | үстелдің үстінде | Korean: | 책상 위에 | Kyrgyz: | столдун үстүндө |

all of which translate, approximately, as the table on.

Other languages which are right headed include: Telugu, Marathi,

Hindi, Kannada, Gujarati (and nearly all other Indian languages),

many African languages, almost all Austronesian languages and many

North and South American languages.

A third way of ordering things is one used by a smaller number of

languages, albeit with very large numbers of speakers. These

languages use what is known as circumpositions, splitting the

adposition in two with one element preceding the noun phrase and one

following it. Most Chinese languages do this although

postpositions are also common and prepositions occur, too, so the

languages are often classified as having no canonical or default

ordering of the elements.

Circumfixing adpositions is also common in Pashto and other Iranian

languages.

Here's a summary:

A rare form of adpositioning is one used by some Austronesian languages in which the particle is placed within the noun phrase itself. These are, rather obviously, referred to as inpositions.

The implications for learners of non-left-headed-language backgrounds are obvious.

There's a test on much of this.

| Related guides | |

| the word-class map | for links to guides to the other major word classes |

| prepositions of place | for more on specific groups of prepositions |

| prepositions of time | |

| other meanings of prepositions | for a guide to what prepositions mean when not used for time or place |

| meaning patterns | for a PDF document with the tables of types of complementation above |

| case | for much more on how other languages indicate the relationships signalled in English by prepositional phrases |

| sentence stress | for more on how phrases are stressed |

| constituents of phrases | for more on ambiguity and phrase constituents |

| ambiguity | for more on how prepositional phrases may be sources of ambiguity and disambiguation |

| modification of nouns | for more on modification of noun phrases |

| modification: essentials | the general guide in the initial plus section |

| post-modification of noun phrases | for more on how prepositional and other phrases function to modify or define nouns |

| pre-modification of noun phrases | |

| adverbials | for more on adjuncts, disjuncts and conjuncts |

| multi-word verbs | for more on prepositional verbs or verbs with dependent prepositions |

| adverbs | for more on how and which adverbs function as complements of certain prepositions |

| adjectives | this guide contains more detail about how prepositional phrases act as complements to adjectives |

| introduction to prepositions | for a simpler guide to the area |

References:

Chalker, S, 1984,

Current English Grammar, London: Macmillan

Dryer, MS and Haspelmath, M (Eds.), 2013,

The World Atlas

of Language Structures Online, Leipzig: Max Planck Institute

for Evolutionary Anthropology, Available online at https://wals.info

Quirk, R, Greenbaum, S, Leech, G & Svartvik, J, 1972,

A Grammar of

Contemporary English,

Harlow: Longman