Ambiguity

This is quite a long guide with separate sections, not necessarily

connected or following on from each other.

If you are here for the first time,

and just want to get an overview of the scope of ambiguity and the

various classifications we can use, work through it

sequentially but if you are returning to check something, here's a list

of the contents to take you to its various sections.

Links in bold are to major sections, others lead to

subsections.

Clicking on -top- at the end of each section will

bring you back to this menu.

Ambiguity is not, of course, a phenomenon which is confined to

English. All languages can be used in a way that allows two

possible interpretations, sometimes more, of what seems to be a

simple enough statement or question.

In English, for example, the following has recently occurred:

He: Welcome

home. I've saved you a job.

She: Thanks, that's good of you.

He: Don't be sarcastic.

She: What?!

|

Task: What has gone wrong? Think for a minute and then click here. |

The answer lies in the polysemous nature of the verb save. It has more than one meaning although the meanings are clearly connected.

- It means set aside for action or use in the future

as in, for example:

I have saved enough money for my holiday

I have saved the best idea till last - It means avoid having to use or do as in, for

example:

I have saved an hour's work by using the new program

She has saved the company lots of money - It also means rescue as in, for example:

She was saved from drowning

The castaways were saved by a passing fishing boat

of course but that is not relevant here.

What has happened in this little dialogue is:

- He is using the verb to mean

set aside or keep for later (meaning 1., above) but she has understood that it

meant avoid having to do something (meaning 2.).

Naturally, he expected her not to be delighted to be told there was a job waiting to be done, having been saved for her, so he interprets her thanks as being an attempt at sarcasm. - She, on the other hand, have assumed that the second meaning of the verb

save,

is understandably confused at being accused of sarcasm because

the thanks were sincerely intended.

What we have is an example of lexical ambiguity inherent in the polysemous nature of the verb.

Many of the examples below are culled from other guides on this site in which ambiguity is considered almost in passing. Here, it is the focus.

|

Sources of ambiguity |

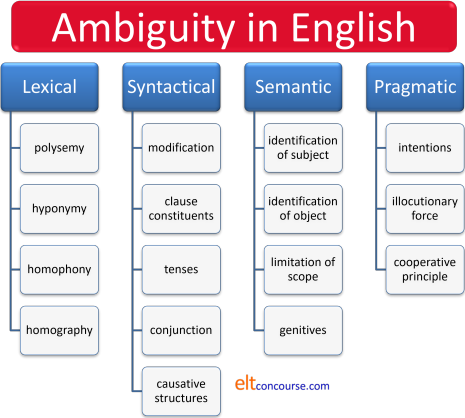

This guide considers three main possible sources of ambiguity, explains what the problem is and tries to suggest some ways to remove the ambiguity. The three are:

- Lexical ambiguity

The source for this is the fact that some words have homonyms which look and sound the same but carry different meaning.

In spoken language, homophones will have the same issues and in written language homographs may also be a source of ambiguity.

The issue we saw above with the word save is not, however, to do with homonymy; it concerns polysemy, the phenomenon of words have different but connected meanings rather than different and unconnected meanings. The borderline between homonyms and polysemes is, however, somewhat blurred.

There is a guide to the polysemy, linked below in the list of related guides at the end.

Here are some examples of what is meant:

It is unlikely that any of these examples set in context, will produce a great deal of ambiguity, of course, but, standing alone, they cannot be disambiguated.Issue Example Meaning 1. Meaning 2. homonymy They found the quarry They found the animal they were hunting They found the source of building stone polysemy What did you read last year? What did you study at university? What reading did you do last year? He may come He has permission to come It is possible he will come grey area She took a taxi She used a taxi as transport She stole a taxi homophony The border / boarder is here The edge / frontier is here The paying guest / tenant is here homography He bought a new bow He bought a new violin accessory He bought a device for shooting arrows - Syntactical ambiguity

There are a number of ways ambiguity can arise from the syntax of a sentence or clause and they are mostly to do with what modifies what or what qualifies as an independent constituent of a sentence or clause (related areas as we shall see).

They can also be to do with how tense forms in English are understood and how subordination and coordination are understood.

Here are some examples:

Syntactical ambiguity arises from the phenomenon of syntactical homonymy and can sometimes be almost impossible to untangle without reconstructing the clause or sentence.Issue Example Meaning 1. Meaning 2. modification I said I would come on Monday I said this on Monday I will come on Monday Being honest, he was seen as rude My honest opinion is he was seen as rude Because he was honest he was seen as rude independence I washed the car in the corner I washed the car which was in the corner It was in the corner that I washed the car I spoke to the man in my office I spoke to the man who was in my office It was in my office that I spoke to the man tense form I'm driving to London this week Sometime this week I will drive to London It is my temporary habit to drive to London The professor is writing to the students The professor is currently writing The professor intends to write conjunction She was exhausted but Mary worked on Mary and she are the same person Mary and she are different people Someone stole my car so that I had to take the train The result of the theft was that I took the train The purpose of the theft was to force me to take the train - Semantic ambiguity

Some see this as a subset of syntactical ambiguity but it is noticeably different because much depends on the shared knowledge and speaker perception rather than simply the syntax. It concerns what is meant, not what is necessarily understood by decoding the syntax.

Here are some examples:

The last example is called by some anaphoric ambiguity because it is impossible to know which referent is appropriate for he.Issue Example Meaning 1. Meaning 2. who does? John and Peter have a house in London John and Peter share a house in London John and Peter have separate houses in London what is the object? John used his own car and so did Mary Mary and John used John's car Mary and John used their own cars limitation The tiger is a dangerous animal This particular tiger is dangerous Tigers are dangerous what is the subject? John saw the boss and he asked him to wait John asked the boss to wait The boss asked John to wait

At the end we will also consider a fourth source of ambiguity which is not dependent on language use but which stems from social and cultural sources.

|

Lexical ambiguity |

It is quite rare for a lot of polysemes and homonyms,

especially those concerning content words, to cause a great

deal of difficulty because the context almost always determines the

meaning that is meant.

We are unlikely to misinterpret, for example:

I took an aspirin

as

I stole an aspirin

or

She dug the garden

as

She appreciated the garden

although misunderstanding is always possible if the context is

too thin.

Function words and auxiliary verbs are a very different matter because

the meaning they convey relies on the co-text.

Here are some examples but no guide to ambiguity can ever cover all

the possible sources.

|

will and other modal auxiliary verbs |

|

Will you marry me? Well, will she? |

The verb will is polysemous because it applies to a future time

in one sense and to a current willingness in another. So,

Will you marry me?

concerns the woman's current willingness to commit to something,

but

Will she marry him?

is a question requiring speculation about the future.

In the first example, the modal auxiliary verb refers to dynamic

modality (volition) and in the second to epistemic modality

(propositional truth).

That is the reason that will can appear in both parts of a

conditional sentence such as:

I will give you a lift if you will share the

petrol costs

Normally, the rule is not to use will in both clauses

but it is correct here because the first incidence of will refers to the future

and the second refers to the hearer's willingness to do something.

It is only useful to tell learners that we cannot use will

in both parts of a conditional sentence if we are clearly using the

verb in one of its main meanings. In other words, being

careful to avoid ambiguity.

A fundamental reason why modal auxiliary verbs cause so much

trouble for learners is their polysemous nature.

Here are some examples of what is meant:

| Verb | Example | Meaning 1. | Meaning 2. |

| might | She said they might ask questions at the end | She gave them permission to ask questions | She thought it was possible they would ask questions |

| may | They may go | They have permission to go | They might go |

| He may not come | I will allow him not to come | He might not come | |

| can | Can you help her with her homework? | Please help her with her homework | Are you able to help her with her homework? |

| You can talk to him | I give you permission to talk to him | He is approachable | |

| †I can not smoke | I have the ability not to smoke | I am not allowed to smoke | |

| would | He would be rude to his mother if she asked a question | He was habitually rude to his mother when she asked a question | If his mother asks a question his response is likely to be rude |

| could | She could explain it more clearly | She was able to explain it more clearly | She should explain it more clearly |

| It could bend | It has a flexible nature / ability | It is possible that it will bend | |

| I could have left it with John | John gave me permission to leave it with him | It is possible that I left it with John | |

| If you come late you could miss the speeches | It is possible you will miss the speeches | You will be able to miss the speeches | |

| ought | He ought to be there | I expect he is there | He has an obligation to be there |

| must | He must be at home | I am certain he is at home | He is obliged to be at home |

| have to | He has to be at home |

The moral is that all modal auxiliary verbs have the possibility

to be interpreted in multiple ways.

Elsewhere on the site, the verb could is shown to have

eight possible meanings (present possibility, future possibility,

past possibility, present ability, future ability, past ability,

permission, complaint), might has six (present possibility,

future possibility, past possibility, suggestion, permission,

complaint) and even should has four (advice, obligation,

conditional uses, logical deduction).

Other modal auxiliary verbs, especially the central nine, suffer

from the same ambiguity of modality type.

|

adjectives |

| The hardworking students passed |

Scope

This sentence:

The hardworking students passed the examination

is ambiguous because this may mean either:

The students who worked hard passed the examination

(and other

students, less hardworking, did not)

or

The students, who worked hard, passed the examination

(all of them were hardworking and all of

them passed)

Other adjectives are open to similar multiple interpretations.

For example:

The available money is inadequate

in which the adjective available can mean:

all the money (with no more to come)

the money available now (with more to come)

This can be disambiguated in two ways:

- By making a relative pronoun clause and distinguishing

between defining (restrictive) and non-defining (unrestricted)

forms:

The money, which is available, is inadequate

(i.e., it is all available)

vs.

The money which is available is inadequate

(i.e., only the money which is available, not all of it) - By post-positioning the adjective:

The available money

all of it

vs.

The money available now

some of it with more to come

The second disambiguation trick works with other adjectives as

in:

The visible stars

The stars visible tonight

The present staff

The staff present now

The first refers to all the visible stars, the second to only

those visible tonight, the third to the entire staff at the moment

and the fourth to only those employees who are here.

Determining how an adjective should be understood in the sense of what is included and what excluded is not always simple. It is not that we have a polysemous word acting as an adjective (although that happens) but where the scope of modification starts and stops.

The adjective bad is somewhat ambiguous in this respect. For

example:

She felt bad

could imply that she felt unwell or that she felt guilty although

this can be disambiguated with the use of the adverb so:

She felt badly

can only mean unhappy or guilty, not unwell.

Classifiers, epithets and punctuation

There is some ambiguity in written language whether a word is

intended as an adjective (an epithet) or a classifier because:

a senior school teacher

could be interpreted as

a teacher at any type of school who is

experienced and older

or

a teacher who happens to work in a senior school

In the former, the word is adjectival and in the latter it is a

classifier.

Commas are often optional but required when there is possible

ambiguity. For example:

It's a large house plant

is unlikely to be misunderstood as a plant only for use in large

houses but to avoid any ambiguity, it can be written as

It's a large, house plant

Compare:

It's a small garden plant

in which there is ambiguity which can be eradicated by punctuating

it as

It's a small, garden plant

or

It's a small-garden plant

old and new: inherent and non-inherent

meanings

The adjective old may be applied to inanimate and animate nouns

but when it is applied to animate nouns the meaning will vary

depending on how it is used (attributively or predicatively).

So, for example:

He is an old friend

will be understood non-inherently as applying to a long-lasting

friendship, not to the person but

My friend is old

will be understood as applying to the friend, not the friendship.

Unfortunately the word old has two common antonyms: new

and young and they are differently understood depending on

the nature of the noun to which they are applied.

So, for example:

She's a new friend

and

All these students are new

will not be seen as applying to the people but to their recent

arrival whereas

She's a young friend

or

The students are young

can only be understood as applying to the people directly.

However:

There's a new car in the car park

and

That car in the car park is new

are truly ambiguous and could mean

The car has only recently appeared in the car

park

or

The car has recently been manufactured

and only context can disambiguate the meaning.

A further, connected source of ambiguity lies in the fact that

some adjectives can apply to a person and to a relationship so, for

example, while it is clear that:

She's a new friend

They are old rivals

both apply to the friendship and the rivalry, not the people

involved, it is less clear whether the adjectives in

He's a reliable friend

She's a remarkable friend

refer to a reliable / remarkable person or a reliable /

remarkable friendship.

Ambiguity can be avoided by using the adjective predicatively

because then the assumption will always be that it applies to the

person:

My friend is reliable

Her friend is remarkable

Comparative forms

The question here is whether the words more and less

are acting as adverbs modifying adjectives or as determiners

modifying noun phrases. It matters because the meaning changes

depending on the grammatical function of the word. In that

sense, this straddles the boundary line between lexical and

syntactical ambiguity.

Here are three examples:

- They provided more accurate figures

- = They provided more

figures which were as accurate as the old ones

or - = They provided figures which were more accurate than the old ones

- = They provided more

figures which were as accurate as the old ones

- I want more useful work from you

- = I want more work from you which

is as useful as the work you have done

or - = I want work from you which is more useful than the work you have done

- = I want more work from you which

is as useful as the work you have done

- She had less expensive work done

- = She had less work done which

was as expensive as the previous work

or - = She had work done which was not as expensive as the previous work

- = She had less work done which

was as expensive as the previous work

The ambiguity arises from the fact that in:

i.a., ii.a. and iii.a., the words more and less

are determiners referring to the noun phrases accurate figures,

useful work and expensive work

but in:

i.b., ii.b. and iii.b., the words more and less

are adverbs modifying the adjectives accurate, useful and

expensive

It is impossible to tell by looking at the sentences what the words more and less are doing grammatically. Rephrasing as above will remove the ambiguity.

Superlative forms

Compare

The girl is most intelligent

and

The most intelligent girl

both of which are possibly ambiguous because they can mean

either:

The very intelligent girl

or

The girl who is more intelligent than the all

the others

The use of the definite article determiner can disambiguate

this because

The most intelligent girl

will only be understood in the second sense.

The key here is not to word class because in all the examples, the

word most is an adverb modifying the adjective.

However, the word is polysemous because is means very or

extremely and it forms the superlative of an adjective

expressing the uppermost degree.

|

Syntactical ambiguity |

Much of syntactical ambiguity arises from the possibility of, so

to speak, throwing a mental switch to decide which line to take.

Tense forms in English, or most languages, do not have a one-to-one

relationship with time. We use, therefore, present and past

tenses to talk about the future, past tenses to talk about the

present and so on.

There is a good deal more about this in the guides to time, tense

and aspect, linked below, so some examples of the possible

ambiguities will be enough here.

|

-ing forms |

| He's driving |

At first sight, a sentences such as:

He's driving

is not ambiguous, especially when it's linked to an image as here.

However it can mean:

- Driving is what he is doing right this minute

He won't answer his phone. He's driving. - Driving will be his preferred mode of travel for the

foreseeable future

He's driving to work these days because the trains are so unreliable - Driving will be a temporarily habitual form of transport

I don't need the car for a while so he's driving to work at the moment - Driving is what he has agreed to do in the future

I can have another beer because he's driving me home later

This is where we encounter a famous Chomskyan concept.

Chomsky, to whom there is a guide linked at the end, chose to

demonstrate what he meant by deep structure with the example

sentence:

Visiting aunts can be boring

because that can mean:

Aunts who visit can be boring

or

The activity of paying a visit to aunts can

be boring

It is, in fact a bit of a four-way cheat in our terms here because the ambiguity relies on:

- Selecting a transitive verb so that there is manufactured

ambiguity concerning subjects and objects. You cannot, for

example, construct a similarly ambiguous sentence with verbs

like arrive or speak because you get the

unambiguous:

Speaking clocks can be irritating - Selecting a semantically allowable transitive verb. You

cannot, for example, construct a similarly ambiguous sentence

with verbs like explain or show because you

get the unambiguous:

Showing your anger can be inadvisable - Using the uninflected modal auxiliary verb, can, to

disguise the verb-noun concord. You cannot, for example,

construct a similarly ambiguous sentence without the modal

auxiliary because that produces:

Visiting aunts bore me

Visiting aunts bores me

which contain no ambiguity because the first has a plural noun as the subject and the second has a singular gerund as the subject. We don't need to think about deep structure to disambiguate the sentences, simply leaving out the modal auxiliary verb will do. - Selecting a verb which has a gerund form (a verbal noun) and

a participle form which can act as an adjective. You

cannot, for example, construct a similarly ambiguous sentence

with verbs like wear or repair because neither

wearing nor repairing can operate as participle adjectives

although the verbs are transitive.

We allow:

Wearing warm clothes can be useful

Repairing computers needs some care

but not:

*These are wearing clothes

*He is a repairing man

It is quite difficult to make a parallel sentence to the one

Chomsky used although:

Eating apples can be healthy

Drinking water can be good

Cleaning materials may be expensive

Burning rubbish could be dangerous

and just possibly

Climbing plants can be dangerous

(if you are a field mouse)

will show the same kind of ambiguity.

The parlour game is to think of ten more.

In fairness, this was not the point that Chomsky was making.

He used ambiguity as a way of revealing the inadequacies of a

structuralist approach to grammatical analysis and was not concerned

with communicative effect.

Tense-form ambiguity is a much more important issue for teaching.

|

Other non-finite -ing forms |

Misuse of the -ing participle in non-finite

clauses often results in what is called a dangling or unattached

participle. For example:

Getting on the bus, John's wallet fell

from his pocket

is semantically and grammatically flawed because it was not the

wallet that got on the bus.

To avoid this kind of ambiguity, the participle and the main clause

verb need to have the same subject. The use of a finite

clause solves the issue:

While he was getting on the bus, John's

wallet fell from his pocket

In this case, little ambiguity is caused because we know

that wallets do not, of their own volition, take public transport.

However, there are times when the rule is not quite so clear cut.

For example:

I saw Mary getting off the bus

is likely to be interpreted as:

I saw Mary while she was getting off the bus

but could mean:

While I was getting off the bus, I saw Mary

We need to be more careful here because both the possible

subjects are able to take public transport.

In order to repair the ambiguity, we have to rephrase the sentence

as:

I saw Mary when she was getting off the bus

or

I saw Mary when I was getting off the bus

The rule of attachment to the same subject is often relaxed

so we allow:

Being Friday, the staff left

early

which is not ambiguous because the staff cannot be Friday.

On the other hand,

Being optimistic, Mary will

be able to do the job

is ambiguous depending on whether the speaker

or Mary is the optimist.

The ambiguity here is explained a little more (and a little more

clearly) below, under semantic ambiguity.

These sorts of non-finite clauses used to express temporal or causal

relationships can give rise to some ambiguity of meaning.

For

example:

Being in New York, she went to see him

could mean:

While she was in New York, she went to see him

or

Because she was in New York, she went to see him.

In all such cases, rephrasing the thought using finite rather than non-finite verb forms solves the problem as can using the right subordinating conjunction as in the examples above.

|

Adverbial modification |

| He quickly got lunch |

It is often difficult to determine which verb an adverb modifies

when there are two verbs in the same sentence. For example:

The people who came quickly got lunch

has two interpretations depending on which verb is being modified by

quickly:

- The modified verb phrase is came, in which case we

have:

People who were quick to arrive got lunch - The modification belongs with the verb got, in

which case we have:

The people who came got lunch quickly

We can rephrase this to remove the ambiguity as we have done

here. The key is to put the adverb in the right place.

It can also be disambiguated by pausing in speech after quickly

(and signalling sense 1.) or after came (and signalling

sense 2.).

That is straightforward with middle-position adverbs such as those

of manner which are mobile but even easier with adverbs of

indefinite frequency as in, e.g.:

The men who arrived late frequently missed

lunch

vs.

The men who frequently arrived late missed

lunch

because these adverbs conventionally precede the main verb.

There are also times when it is not clear whether an adverbial is

functioning to modify a verb or its subject or object.

For example, in:

His friends at that time were working

could mean:

- His friends were working at that time

which modifies the verb phrase, or - The friends he had at that time were working

which modifies the noun phrase

and unless we know whether the prepositional phrase is modifying

the noun or the verb phrase,

we cannot arrive at the meaning. This is an example, arguably,

of phrase constituent ambiguity, which is considered in much more

detail later. The concepts of syntactical and

phrase-constituent ambiguity overlap with blurred edges.

Simple rephrasing (as above) will disambiguate the meanings.

Finally, there are times when an adverbial can apply to either of

two verbs. When verbs form strings in the syntax (i.e., they

catenate) some ambiguity sometimes arises in deciding which verb the

adverbial is modifying so, for example, in:

She undertook to do the work straightaway

it is not apparent whether

- the undertaking happened immediately

in which straightaway is modifying the verb undertake, or - the doing of the work will happen immediately

in which straightaway modifies to do the work

The intuitive response from many will be that the adverbial

modifies the nearest verb so interpretation b. is probably inferred.

We can disambiguate the sentence by moving the adverbial and

producing:

Straightaway, she undertook to do the work

which signals interpretation a.

|

Conjunctions |

Some conjunctions cause ambiguity issues.

although and while

Both although and while are subordinating

conjunction of concession and occur unambiguously in, for example:

I like reading in the evening while my

husband prefers watching TV

Although I like reading in the evening, my husband prefers

watching TV

etc.

A little care is needed, however, because while is also

a temporal subordinator so, for example:

Although it is raining, I'll take a walk

is unambiguous because although has only one function

but

While it is raining, I'll take a walk

can mean:

Although it is raining I'll take a walk

or

As long as it is raining I'll take a walk

It could also mean:

Because it is raining I'll take a walk

because while sometimes carries the sense of causality

usually signalled by so or because.

but and although

There is also scope for ambiguity with the distinction between

coordinators and subordinators.

In coordinated clauses

we can omit the subject, providing it is common to both clauses so we get, for example:

Mary was exhausted but worked on till six

in which it is clear that Mary is the subject of both clauses.

We cannot do this with subordination so we do not allow:

*Although Mary was very tired, worked on till six

There is, however, a little more to it than that because in a

sentence such as:

He was exhausted but John worked on till six

it is averred by some that He and John must refer

to different people. In other words, He cannot be a

cataphoric reference to John in a coordinated sentence.

This is somewhat questionable and the sentence is at best ambiguous

insofar as He and John could refer to the same

person or to different people depending on context and co-text.

With subordination, on the other hand, cataphoric reference is

assumed so in:

Although he was exhausted, John worked on

till six

it is inevitable that he and John will be assumed

to be the same person.

so and so that: purpose or result?

The conjunction so also causes problems because it

implies both a result and a cause.

It is resultative in, for example:

The night was very clear so I could see the

ships out to sea

It is causative in, for example:

I dug a deep hole so the tree was firmly

planted

However, ambiguity can arise with a sentence such as:

Someone stole my car so I couldn't get to work

which means either:

- The result of the theft of my car was that I couldn't

get to work

or - Someone stole my car to prevent me getting to work

The way to disambiguate is to replace so with because when we are

referring to result and then we get:

Because someone had stolen my car I couldn't

get to work

which is unambiguous, or to rephrase the thought as in b.

The same consideration applies in these examples.

It is resultative in:

The ground was icy so that I was careful how

I walked

in which the care is a result of the ice and so that

is acting as a coordinating conjunction.

It is, however, purposive and a subordinating

conjunction in:

I put salt on the driveway so that the ice

would melt

This means that, e.g.:

He was standing in the light so that I could

see him

is ambiguous and means either:

- The result of his standing in the light was to make him

visible

(coordinating the clauses)

or - He stood in the light in order to make himself visible

(subordinating the second clause to the first)

Again, we have to rephrase to exclude the possibility of ambiguity.

before

Temporal conjunctions can also cause ambiguity if handled

carelessly. For example:

I expected he would be happy with the figures before the meeting

started

can be interpreted either as:

- Before the meeting started, I expected he would be happy with the

figures

or - That he would be happy with the figures before the meeting started was what I expected

The ambiguity can be resolved by moving the temporal clause to the initial position as in a.

if and when

The conjunctions if and when also cause

problems. In, for example:

When possible, the work should be completed

without disturbing the residents

has two interpretations:

- Whenever it is possible, the work should be completed

without disturbing the residents

or - If it is possible, the work should be completed without disturbing the residents

Resolving the ambiguity simply means being careful to use if when a conditional rather than temporal meaning is intended.

if and whether

Consider:

Tell me if you need any help

which has two interpretations:

- Tell me if you need any help

as a true conditional in which the imperative depends on the need for help

or - Tell me whether you need any help

which is not conditional and simply asks for the speaker to be informed

Disambiguation again involves using if only in conditional senses.

because

Some ambiguity may arise with negative causality so, for example:

I didn't come because of the chance that she would be there

may be interpreted either as:

- The reason I didn't come was because there was a chance

she would be there

or - The reason I came was not that there was a chance that she would be there

Only context and intonation (stressing because) will disambiguate

the meaning unless we rephrase the whole meaning as:

There was a chance she would be there so I

didn't come

and

That there was a chance she would be there

was not the reason I came.

This is also considered below when we come to the ambiguity

that negative sentences can evince.

to and in order to

The word to is sometimes just an abbreviation

of in order to.

This can create some ambiguity.

Compare for example:

- I agreed to go to the restaurant

- I agreed to get a bit of peace.

In the first case, we have a to-infinitive doing its

usual catenative job referring to a prospective event.

In the second case, however, to is an abbreviation of

in order to and is not catenative.

Here's a slightly different example:

- I agreed to the proposal to finish the meeting early

is ambiguous because it means either:

- I agreed to the proposal that the meeting should finish

early

or - I agreed to the proposal in order to finish the meeting early

and only rephrasing such as above can disambiguate the sentence.

|

Clause constituents |

This is a major area of ambiguity and the final one to tackle

under syntactic ambiguity.

There is a dedicated guide to disentangling clause constituents on

this site, linked below, so here we will rely on a few examples of

the sorts of ambiguity that can arise.

Here are the examples:

Instrumental phrases

Many case-grammar languages have a way of marking instrumental

case but English doesn't, preferring to rely on prepositional

phrases. Unfortunately, prepositions themselves are

polysemous. The preposition with carries the meaning of an

instrument as in:

I cut down the tree with an axe

and of accompaniment as in:

The man in the corner with the dog.

This causes problems.

For example:

Anne hit the intruder with a chair

is probably not ambiguous at all (but it is conceivable that

the intruder was carrying a chair).

Anne shot the intruder with a knife

is also unambiguous because you can't shoot someone with a

knife so the only interpretation is that the intruder carried the

knife.

However,

Anne hit the intruder with a gun

is truly ambiguous because it can be interpreted as either:

- Anne used a gun to hit the intruder

or - Anne hit the intruder who was carrying a gun

So rephrasing is necessary to make the sense clear.

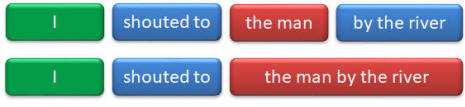

Prepositional phrases as modifiers of nouns or verbs

Take:

I shouted to the man by the river

which has two interpretations:

- By the river I shouted to the man

or

It was by the river that I shouted to the man - I shouted to the man who was by the river

or

It was the man by the river that I shouted to

It depends on whether we consider by the river to be an

independent phrase or one which is attached to the noun.

The subject of the sentence is clear: it is I.

The object, however, can either be:

- the man by the river

or - the man

The adverbial phrase which modifies the verb is then absent (if

a. is the object) or is by the river if b. is the object.

In other words, we have to decide whether the shouting happened by

the river or not.

We can use a diagram to make it clear:

In the first case the verb phrase in blue has the blue adverbial

modifying it with the verb's object in red. The phrase by

the river is independent and can be moved to the beginning to

get:

By the river I shouted to the man

In the second case the verb phrase is unmodified and the object is

in red but by the river is not an independent phrase

because we cannot move it to the beginning and retain the same

sense.

Here are some more examples taken from various guides on this site for you to untangle:

- He used the computer in his office

- Which computer did he use?

- Where did he use the computer?

- The teacher shouted at the boy in room 13

- Where did the shouting happen?

- Which boy did the teacher shout at?

- He cut up the tree in the corner

- Which tree did he cut up?

- Where did the cutting up happen?

- John upset the lady in the garden

- Who did John upset?

- Where did the upsetting happen?

- He read the book on the island

- Where did he read?

- What was the subject of the book?

Disambiguation in writing

In written language, it is impossible to disentangle independent and mobile phrases so rephrasing is the option. This often means:

- Moving the prepositional phrase:

At his office he used the computer - Making a cleft sentence:

It was the boy in room 13 that the teacher shouted at - Otherwise defining the object:

He cut up the corner tree - Making a passive:

The tree in the corner was cut up - Using a relative pronoun clause:

John upset the lady who was in the garden - Changing the prepositions and producing, e.g.:

He read the book about the island

Disambiguation in speaking

In speaking we can deliberately move the tonic syllable to disambiguate what might otherwise be unclear. For example, the sentence:

Anne hit the man with the chair

has two possible interpretations as we saw.

We can disambiguate this in speaking by paying attention to how the utterance is stressed. Like this:

| 1 | Anne | hit the | MAN | with a chair |

| pre-head | head | nucleus | tail | |

| 2 | Anne | hit the man with a | CHAIR | |

| pre-head | head | nucleus | - |

In case 1, the pitch movement is most obvious on the word man

so that becomes the focus of attention.

In case 2, chair is the focus because that is where the

pitch movement occurs.

Disambiguating which meaning is intended by pausing and tone shifts

are what Wells refers to as the demarcative function of intonation,

i.e., the separating off of the crucial data.

Position and direction adjuncts

The usual rule in English is that position adjuncts cannot

co-occur with dynamic verbs of motion but directional adjuncts of

place can so we do not allow:

*He is climbing at the top

because at

refers to place, not direction,

but we do allow

He is climbing to the top

and

He is sitting at the top.

An ambiguity can arise, therefore, concerning whether, for

example:

The children were running outside

means:

When the children were outside, they were

running

or

The children were in the process of moving

from inside to outside

Usually, the assumption will be that direction of movement is

the intended message but that is not always the case.

Because some prepositional adjuncts are always directional, the

ambiguity cannot arise, for example, with:

I'm going to walk into the garden

but can with the preposition in and outside

which refer to both direction and position so

He walked in the airport

might mean he did some walking in the airport or that he moved

into the airport on foot and

They threw it outside the house

might mean they threw it from inside to outside or that it was

outside the house before they threw it.

The former is what people will usually understand.

yes-no questions

Nearly all yes-no questions are, by their nature

ambiguous in terms of what they are asking. Really simple

questions such as:

Is John here?

are not ambiguous because the direction of the question can only be

John's presence or absence.

However, a question such as:

Did Mary cook the turkey last night?

contains four phrase elements (the subject, the verb phrase, the

object and the adverbial of time). It means, therefore, that a

yes-no question could be directed at any of these

constituents. Like this:

Was it Mary who cooked the turkey last night?

Was it last night that Mary cooked the turkey?

Was it the turkey that Mary cooked last night?

What did Mary do to the turkey last night?

and only the co-text and context can disambiguate this in writing

although sentence stress can make the sense clear in spoken

language by stressing Mary, last night, the turkey and

do respectively.

The disambiguation which the cleft forms allows is, incidentally,

one of the motivations for their use although, as we see from the

fourth question, the verb

cannot be the focus of a cleft sentence form and the question is

differently formed. We cannot allow:

*Was it cook that Mary did to the turkey last

night?

There is more on cleft sentences in the guide to them, linked below.

|

Causative structures |

You are probably aware that two verbs in English, have

and get, function in causative structures to place the

focus on what is done rather than who did it. So, for example,

it is easy to see that:

I got my house painted last year

and

I had the report re-written with the new

figures

both signal the fact that the speakers / writers did not affect

the action personally but persuaded, cajoled, required or paid for

others to do it for them. (The guide to the causative which

explains how this is achieved is linked below.)

Unfortunately, the structures themselves allow of multiple interpretations and, in many cases, only context and co-text can help us to the meaning.

Ambiguity arises because the structures themselves are used to signal different meanings so, for example:

- Often the meaning is transparent so, e.g.:

She had her car repaired by the garage at the end of the road

or

She got her car repaired by the garage at the end of the road

are both unambiguously causative structures which signal what she required the garage to do. - She had her car stolen for the insurance money

and

She got her car stolen for the insurance money

both refer to a fraudulent act. - She had her car stolen while she was on holiday

and

She got her car stolen while she was on holiday

both probably refer to an unfortunate event. - She had her foot caught in the lift doors

refers to an unfortunate state or event and is not causative

but

She got her foot caught in the lift doors

can only refer to an unfortunate event not a state but is similarly not causative.

So, standing alone, a sentence such as:

She got the safe broken open

can carry three different senses (fraudulent act, misfortune or

simple causative).

Context is needed to know which is the correct interpretation.

Unfortunately, again, both verbs can signal the speaker's

accomplishment, not the fact that the speaker did not perform the

action personally. Further ambiguity arises because English

does not distinguish the form of a participle used verbally and one

used adjectivally. So, for example:

I got the report finished on time

will usually be interpreted as

I succeeded in getting the report finished on

time

and

I had the report nearly finished when the new

figures came in

signals the fact that the report writing was almost

accomplished. In both cases, the word finished is

interpretable as a participle adjective equal to a (nearly)

finished report .

When the context and co-text do not help, however, ambiguity arises

so, e.g.:

I need to get the car washed for the wedding

can mean:

I have to wash the car for the wedding

or

I have to have the car washed for the wedding

and only context and co-text can disambiguate the senses.

Compare, too, for example:

I go the kitchen floor swept and mopped by

six o'clock

which almost certainly refers to the speaker's achievement,

with:

I got the kitchen floor swept and mopped by

the maid

which is clearly causative.

No ambiguity can arise, therefore, when the adjective is not

derived from a verb so:

I got the figures right

and

I had the figures right

are unambiguous, but

I got the figures worked out

and

I had the figures worked out

are both ambiguous.

These uses of ostensibly causative structures when no causal effect

is implied is non-intuitive and confuses learners easily.

|

Semantic ambiguity |

Now we come to semantic ambiguity caused mostly by the hearer's inability to understand what belongs to what in the utterance.

|

Genitives |

| the gardener's shed |

The genitive in English does more than refer to possession and therein lies a good deal of scope for ambiguity.

In the example above of the shed, for example, it is unclear whether the reference is to:

- a particular gardener's workplace (association)

- a shed owned by a gardener (possession)

- the type of shed typically used by gardeners (description)

Additionally:

- a young man's job

does not necessarily refer to a job held by a young man but refers to a type of physically demanding work - a doctor's surgery

does not usually refer to a surgery owned by a doctor but one in which a doctor (any doctor) carries out medical work - an agricultural worker's cottage

is most unlikely to belong to a particular worker but describes a type of modest building

Rephrasing is the only way to disambiguate but it is often a clumsy alternative and many prefer to leave the ambiguity standing and rely on the context to make it clear which meaning of the genitive is intended.

Another function of the genitive is described as

objective insofar as it refers to the object of a verb. For example:

the woman's imprisonment

probably refers to the fact that the woman is the object and

was imprisoned but it needn't because it can be a subject genitive

as in:

the woman's imprisonment of the children

in which the woman is the subject and did the imprisoning.

From that we can then abstract a genitive:

the children's imprisonment by the woman.

But, in order to disambiguate, we have to select a different

form of the genitive and use the of-phrase, periphrastic

structure instead of the 's inflexion. Then we can arrive at a distinction between:

the imprisonment of the woman

and

the woman's imprisonment

which is less ambiguous, although still not wholly unambiguous.

Another example is:

the man's investigation

which

could mean:

- the investigation into the man

or - the investigation done by the man

If a. is intended then

the investigation of the man

is preferred (the man was investigated, not the man did the

investigation).

If b. is the preferred sense then

the man's investigation

will be preferred, but ambiguity remains.

The rule of thumb is to reserve the of-formulation for objective

genitives and keep with the 's formulation for humans in subjective

genitive expressions whenever there is a need to avoid ambiguity.

|

Negation |

What do you understand by the following negative statements?

He didn't speak to the girl in the red dress at the party.

She didn't meet the man who bought the house on Thursday.

Both sentences are ambiguous and mean either:

- He didn't speak to the girl in the red dress

or

He spoke to the girl in the red dress but not at the party - She didn't meet the man who bought the house

or

She met the man who bought the house but not on Thursday

(In this case, too, incidentally, we do not know whether the Thursday applies to when she didn't meet the man or whether the man bought the house on Thursday.)

We can disambiguate these to some

extent when speaking by stressing the element we want to negate:

He didn't speak to the girl in the red dress at the

PARTY.

She didn't

meet the man who bought the house on

THURSDAY.

He didn't speak to the girl in the red

DRESS at the party.

She didn't

meet the man who bought the

HOUSE on Thursday.

Or, as we saw above we can subtly alter where the tonic stress

falls.

So, in the first two, we have party and Thursday

as the nucleus with no tail and in the second we move the nuclear

stress to dress and house and have a falling tone

on the tails, at the party and on Thursday.

In written language,

no such resources are available so we have to alter the ordering of the elements to make meaning

clearer.

For example:

At the party, he didn't speak to the girl in the red dress.

On

Thursday, she didn't meet the man who bought the house.

Even then,

some ambiguity might remain so to be 100% clear, we need to rephrase

entirely with something like:

He didn't speak to the girl in the red dress until after the

party.

She didn't meet the man who bought the house until the

following Friday.

As you see, the tendency in English to apply negation to phrases

rather than words can lead to a considerable amount of ambiguity.

A general, if sloppy, rule is:

If the negation is ambiguous, hearers will usually assume that it is the final part of the sentence that is being negated.

So for

example:

He didn't drive

means he travelled in a different way

He didn't drive my car

implies he drove his own or someone else's car

and

He didn't drive my car carefully

will normally be understood to mean:

He drove my car carelessly

rather than

He didn't drive my car

In other words, to re-state the rule slightly differently

If there is a danger of some ambiguity, the scope of negation is confined to the final element of a negative utterance.

Occasionally, especially in writing where the use of emphasis, tone units and special sentence stress is less available, some negative statements can be ambiguous and must be rephrased to make the scope of negation clear.

| She didn't praise any of the children | could mean | She praised no children at all | or | She praised only carefully selected children |

| They didn't drink half the beer | Half the beer remains | More than half the beer remains | ||

| This doesn't affect a few of you | A few of you are unaffected | All of you are affected | ||

| He wasn't promoted due to his working style | There was another reason he was promoted | His working style was the reason he wasn't promoted | ||

| I can't understand all of what he says | I understand nothing he says | I understand some of what he says |

In spoken language, the senses can be disambiguated by stressing

the determiners any and a few, stressing the pre-determiners

half

(of) and all (of), stressing the preposition due to and by placing a rising intonation contour

on his working style.

In written English, that form of disambiguation is not available so

careful writers will rephrase to avoid the possible confusion.

English is unusual in forming what is called transferred negation

(for much more, see the guide to negation, linked below). This

means, for example, that we prefer:

I don't think he's coming

over

I think he's not coming

even though the second of these is more logical.

There is, however, a danger of some ambiguity when negation is

transferred (or understood to be transferred). So, for example:

John doesn't think his sister is happy

can be interpreted two ways:

- John believes his sister is unhappy

or - John does not think his sister is happy, he knows she is.

The second interpretation is rare and will be signalled as such, either by the insertion of an additional clause as above or by heavy emphasis being placed on the main verb.

|

Theme and rheme |

Careless handling of theme and rheme often results in ambiguity

or, at least, some confusion.

For example, if we take the two alternative forms:

- She wanted to see her sister so she took the train to London

- She took the train to London because she wanted to see her sister

we need to understand that they are not synonymous and simply randomly selected alternative forms.

In sentence 1. the Theme is

She wanted

to see her sister

and the rheme is she took a train to London

In sentence 2. the theme is

She took the train to London

and the rheme is she wanted to see here sister

The theme is the jumping off point and the rheme acts to

complete the thought.

Now, because rhemes form the following themes in coherent

English, naturally, the first sentence would be followed by a second

saying something about London (the rheme of the first sentence), such as:

While she was there, she took the opportunity to visit the British

Museum

and the second sentence would be more naturally followed by

something about the sister such as:

She was delighted to see her

If we follow the first sentence with something more appropriate to

the second we get:

She wanted to see her sister so she took the

train to London. She was delighted to see her.

in which we are left in a state of ambiguity regarding who was

delighted to see whom because we have been ambushed by the

incoherent use of theme-rheme structure and expected to read or hear

something about London.

Moral: rhemes are used as themes in following sentences to avoid ambiguity.

|

Case pronouns |

Case is not evident in English except in the realm of pronouns where it is critical to understand what did what to whom or whose item was whose.

Consider these two sentences:

- She likes you more than I

- She likes you more than me

In sentence 1., the meaning is that

She likes you more than I like you

but in sentence 2. it is

She likes you more than she likes me

It is only by insisting on the use of the correct case for the

pronoun that the ambiguity can be avoided so the informal

She likes you more than me

could carry either meaning.

The ambiguity is very common because in informal speech, the

accusative (object) case of the pronoun is conventionally used so,

e.g.:

He likes spicy food more than me

would normally be interpreted as:

He is more fond of spicy food than I am

although, because the accusative pronoun, me, has been

used, it really means:

He is more fond of curry than he is fond of

me

The only way to disambiguate is to use rather formal and

correct language and say:

He likes spicy food more than I

to mean we are comparing tastes, and reserve

He likes spicy food more than me

to mean we are comparing taste for food with liking for a

person.

An additional issue with pronoun forms concerns the fact that the

English system is defective, not always distinguishing case, so, for

example, the pronoun you serves for all cases in English.

It is simply impossible in the following to decide what the sentence

means:

He likes Mary more than you

could mean:

He likes Mary more than you like Mary

or

He likes Mary more than he likes you

|

Adjuncts, conjuncts and disjuncts |

There is on this site a guide to adverbials, linked below. For now, we just need to know that adjuncts modify adjective, adverb and verb phrases, conjuncts link whole clauses and sentences together (which is why they are sometimes called linking adverbials) and disjuncts modify the whole of clauses, not just the verb phrase (which is why they are sometimes called sentence adverbials).

Conjunct problems

If the adverb is not separated by commas or by pausing between

separate tone units from the rest of the clause, then some ambiguity

arises. For example:

Her husband was displeased and she ended up similarly unhappy

means that we are comparing her unhappiness with her husband's

displeasure so the adverb is only modifying the adjective, which is

commonly what adverbs do.

However,

Her husband became displeased and she ended up, similarly, unhappy

betokens that we are comparing her ending up unhappy with her

husband's becoming displeased and the adverb is functioning as a

conjunct linking the whole second

clause to the first.

Fronting the adverbs removes the danger of ambiguity so the adverb

in:

Her husband became displeased. Similarly, she ended up unhappy

is only interpretable as a conjunct.

Disjunct problems

One of the examples in the opening tables was:

Being honest, he was seen

as rude

Which is interpretable in two ways:

- My honest opinion is he was seen as rude

or - Because he was honest he was seen as rude

There, it was listed under syntactical ambiguity but it is also a

semantic problem because the hearer does not know who is being

referred to as honest so the issue considered here.

If the speaker wishes to make it clear that he or she is trying to

be honest then the phrase Being honest attaches to all that

follows. It is a style disjunct because the speaker is

signalling how the hearer should understand what is said.

We can rephrase to remove the ambiguity, of course, as:

Because he was being honest he was seen as

rude

or

If I may speak honestly, he was seen as rude

Other disjuncts can also be interpreted as adjuncts unless the phrasing in speech is carefully produced and punctuation is used successfully. Even then, however, ambiguity can remain without rephrasing the thought. For example:

- To be fair, Mary treated everyone equally

- Who is or was being fair, the speaker or Mary?

- To balance the argument, the man was quite objective

- Who is or was doing the balancing, the speaker or the man?

- Speaking confidentially, the accountant has told me the

truth

- Who is or was speaking confidentially, the speaker or the accountant?

and so on.

All three examples have the disjunct separated off by commas at the

beginning of the sentence as is conventional so they should be

understood as disjuncts referring only to the speaker's style.

They will, however, especially in rapid speech, often be

misinterpreted as reference to the subject and verb phrase so rephrasing is

often the only

solution.

Prepositional phrases, despite the polysemous nature of prepositions

themselves, instead of non-finite verb forms often help so we could

get, e.g.:

In fairness, Mary treated everyone equally

On balance, the man was quite objective

Between you and me, the accountant has told me the truth

|

Limiters |

These adverbials (which are almost always adverbs) limit the range

of the verb in some way. The usual list includes:

She only bought a shirt

They even lied about

the results

They just left it where they found it

I merely asked

She nearly succeeded

I simply want an answer

They need careful handling in terms of word ordering to avoid

ambiguity. Some can act outside the adverb role and even when

they are adverbs, placement is important.

For example:

Only he came to the meeting (nobody else came [determiner])

He only came to the meeting (and did not speak [adverb])

He came only to the meeting (and to nothing else [adverb])

He came to the only meeting (and there was only one meeting

[adjective])

all mean something slightly different as do:

She just washed the shirt

She washed just the shirt

because the first implies that she did nothing else to the shirt and

the second that she washed nothing except the shirt.

In AmE the first sentence can also mean

She has recently washed the shirt.

Other examples of what happens when we move the limiters are:

They lied even about the results

They left it just where they found it (in which the

meaning of just changes from only to exactly)

I want simply an answer

The rule of

thumb to avoid ambiguity is to place the limiter immediately before the item it

modifies.

|

Pragmatic ambiguity |

All speakers of all languages, everywhere, occasionally

misunderstand each other. Most will have some kind of idiom

akin to getting the wrong end of the stick although

whatever it is is unlikely to be about sticks.

There is a guide on this site, linked below, to pragmatics which

covers this area in a little more detail. Here, we will deal

with two related concepts.

|

Illocutionary force |

This is to do with what it is the speaker's intention to

communicate, independent of the form of the language used to realise

the function.

For example, a question such as:

Would you like to try that again?

may, in fact, be an imperative meaning:

That was not good enough. Try again

but, if the hearer and speaker are at odds with what it means the

preferred response of:

OK, sorry. I'll have another go

might be replaced by the dispreferred

No, not really.

It may also be a threat along the lines of:

If you try that again, I will retaliate

but the hearer may not comprehend the intention behind the question

and ambiguity and misunderstanding will occur. There is more

on this in the guide to pragmatics, of course.

|

The cooperative principle |

We owe this concept to Grice (who gets much more discussion in

the guide to pragmatics) who was concerned to elucidate how people

figure out what the illocutionary force is that lies behind the

language they hear or read.

He settled on four maxims, the breaking of any of which will signal

some unexpected intention. The four are:

- Quality: Don't say what you believe to be false.

Breaking this maxim can result in some ambiguity because saying, e.g.:

I don't see the argument

may be ambiguous if the speaker intends to say

I disagree

(i.e., does understand the argument but doesn't like it)

but the hearer understands

Please explain again

and goes on to do so, reiterating the argument to the exasperation of the hearer. - Quantity: Be informative enough and don't over-inform.

Breaking this maxim can also result in ambiguity because if a speaker says, e.g.:

There's someone at the door

the hearer (who has heard nothing) may take that to be simple information on which there is no need to act but the speaker may intend

I know you heard the doorbell and I'd like you to answer it

and is deliberately over-informing to make the point. - Relation: Be relevant.

If, in a conversation about getting the car repaired one speaker suddenly intrudes with, e.g.:

By the way, do you have Anne's phone number?

the hearer may suffer from a good deal of ambiguity until the speaker makes it clear that Anne is a car mechanic. - Manner: Avoid obscurity. Avoid ambiguity. Be

brief. Be orderly.

Any of the many ways in which the language can exhibit ambiguity discussed in this guide, whether lexical, syntactical or semantic, can lead to breaking this maxim.

If, for example, a speaker says:

I expected Mary would meet me before I got to the airport

the hearer may perceive ambiguity in terms of whether the meeting or the expecting happened before the speaker arrived at the airport and wonder if the speaker is being intentionally or accidentally ambiguous. It may take a little while to sort this out.

For more, see the guide.

Summary

Here's a diagram that considers the main areas only:

| Related guides | |

| polysemy and homonymy | for some discussion of the fuzziness of these concepts with more examples |

| time, tense and aspect | for more on the mismatch between tense form and the time it refers to |

| adjectives | for more about post-positioning of adjectives and much else |

| lexicogrammar | for some more about how attention to meaning affects syntax |

| Chomsky | for the guide considering his views on ambiguity and much more |

| clause constituents | for the guide to a major area |

| cleft sentences | for the guide to how particular clause constituents may be marked by alterations to the grammar |

| causatives | causatives are frequently ambiguous and interpretation depends on context and co-text |

| negation | for much more about assertive and non-assertive forms and transferred negation |

| adverbials | for much more about adjuncts and disjuncts (and other things) |

| pragmatics | for the guide which contains consideration of the cooperative principle and more |

Reference:

Wells, JC, 2006, English Intonation: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press