Time, tense and aspect: overview and index

If you feel comfortable with the following concepts ...

- time, tense and aspect

- perfect, progressive, continuous, habitual, iterative, durative and prospective aspects

- the distinction between progressive and continuous aspects

- the distinction between stative and dynamic verb use

- perfective, perfect and imperfect verb forms

- telic and atelic clauses

- finite and non-finite verb forms

... then feel free to use this index to go to the area that interests you.

| Talking about the Present | Talking about the Past | Talking about the Future | Talking about Always |

| There is also a guide to: | |||

| Teaching tense and aspect | |||

Otherwise, read on ...

|

Clearing some conceptual decks |

Before we can look at tense forms, meaning and use in English, we have to get four things clear:

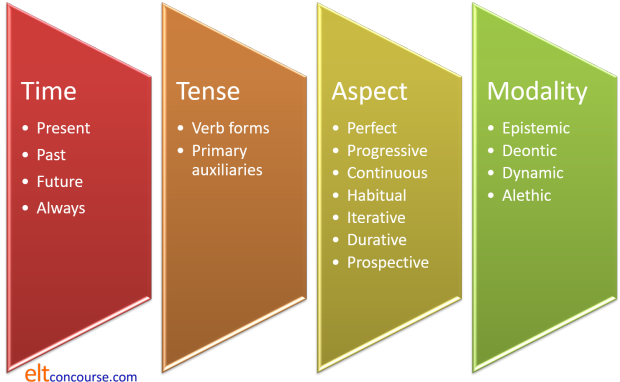

- Time:

- This is a non-linguistic concept of when

an action or a state is set. It is non-linguistic

because the relationship between time and grammatical form is

often unclear with past forms used to speak about the future,

future forms appearing in the past and so on.

Traditionally, we have three choices:- Now: the action / state is set in the present, e.g.:

I am on the train

Please come with me

If you could come with me, it might help - Past: the action / state is set before the present,

e.g.:

She arrived late

I was to have attended the meeting but couldn't be there

Where would he have gone next? - Future: the action / state is set after the present,

e.g.:

My train leaves soon

Do you think she will be at the party?

I will have been here for years by then - but we can add a fourth and that concerns Always: the

action / state is set in the past, the present and the

future, e.g.:

I like apples

She is working too hard these days

We tend to go to bed quite late

This expression of time in a language is often called timeless because it is not, obviously tied to a specific time.

Habitual expressions fall into this category along with expressions of liking and disliking which are assumed to apply to the past, present and future.

- Now: the action / state is set in the present, e.g.:

- Tense:

- No, not that sort.

This is the name we give to the form the verb takes. It refers to the form of the verb and the grammatical function of any primary auxiliary verbs involved. In English it is often averred that there are just two:- past tense: e.g., made rather than make

- present tense: e.g., comes rather than came

- but we'll add a third because English most certainly does exhibit future forms (such as will go rather than goes) even if it has no 'proper' future tense signalled by an alteration in the form of the main verb as many languages do (and many don't)

- Aspect:

- This refers to how the user

of the language views the event or how the event is experienced. There are many

of these and they are signalled in languages in a bewildering

number of ways. For the purposes of analysing English

verb form, meaning and use, we'll focus on:

- perfect: relating two times (past to pre-past, present to pre-present, future to post-future). An alternative way to see this (explained below) is that perfect aspects set times within other times.

- progressive: ongoing

- continuous: current

- habitual: routine

- iterative: repeated

- durative: long lasting

- prospective: looking forward

- Modality:

- The expression of tenses is often allied to modality because, by

definition, the future is uncertain, we may speculate about the

past and we may not be sure of our facts even in the present.

In all tenses, we can speak of our concerns with regard to willingness,

ability, uncertainty, likelihood, permissibility or duty.

Modality concerns the view that the speaker / writer wishes to convey regarding four key concepts:- the truth or otherwise of a proposition: relating to how

the user of the languages perceives the likelihood of

something being the case. For example, expressing

doubt or certainty.

This is known as epistemic modality, from the Greek for knowledge. E.g.:

That might have been her father

She'll probably be late

I expect he's upstairs

etc. - obligation: relating to the language user's

understanding of whether an obligation or its lack is

intended to be expressed. The obligation can vary in

strength and be legal, ethical, moral or advisory.

For example, there is an external obligation, an internal sense of duty, a lack of obligation or an expression of advice.

This is known as deontic modality from the Greek for being a needed duty. E.g.:

They shouldn't have told you that

It would be better if you didn't

You ought to stay

They don't have to go - ability and willingness: this expresses the language

user's view concerning how possible it is for someone or

something to do what the verb suggests or how willing they

are to do it.

Because of the sense of power and willingness, this is called dynamic modality from the Greek for power. E.g.:

I couldn't safely have driven any faster

I won't be able to come

I will get it done for you

I can't help, I'm afraid - necessity: concerns the language user's view of a sense

of inevitability so any statement which implies an

unavoidable logical conclusion falls into this category.

Essential truths about the workings of the natural world or

concepts of definitions of states fall into this category.

It is called alethic modality from the Greek for truth.

If it was the colour you described, it must have been a buzzard

Even on Pluto, Newton's laws will apply

Two and two must make four

- the truth or otherwise of a proposition: relating to how

the user of the languages perceives the likelihood of

something being the case. For example, expressing

doubt or certainty.

Here's the cut-out-and-keep guide to summarise this.

Modality is not included in what follows because that is covered elsewhere in the section dedicated to modality which you can go to here.

|

Some examples to make this clear |

| Example | Time | Tense | Aspect |

| That'll be the postman | Now | Future simple | Continuous |

| he is here now | signalled by the auxiliary, ''ll' + bare infinitive | he is standing outside the door | |

| I have always arrived on Sunday | Always | Present perfect | Habitual |

| signalled by the adverb | signalled by the form of the verb and the auxiliary | this is a routine | |

| He thinks so | Now / Always | Present simple | Continuous |

| this is, was and will be his state of mind | signalled by the -s inflexion | this is a current state | |

| John is writing a book | Now | Present | Progressive |

| this is one of his current occupations | signalled by the auxiliary, is + -ing | this is an ongoing or background action | |

| John is always banging on about it | Always | Present | Iterative |

| signalled by the adverb | signalled by the auxiliary, is + -ing | a repeated action | |

| Murray hits a backhand down the line | Now | Present | Progressive |

| commentary on current actions | signalled by -s | describing an action in progress | |

| I have finished | Present | Present perfect | Perfect |

| describing a current situation | signalled by the form of the verb and the auxiliary, have | the present with an embedded past idea | |

| I leave tomorrow | Future | Present | Simple |

| signalled by the adverb | signalled by base form of the verb with a Ø inflexion | a one-off event | |

| I was staying at the Ritz then | Past | Past | Durative |

| signalled by the adverb | signalled by the auxiliary, was + -ing | the state went on for some time | |

| She lived in France as a child | Past | Past simple | Durative |

| signalled by the prepositional time phrase | signalled by the regular past-tense form | only certain verbs can be used with this meaning | |

| He's going to fall | Future | Present | Prospective |

| signalled by the context | signalled by the verb forms | current opinion of an event after now | |

| What will you do if she doesn't arrive? | Future | Present | Simple |

| signalled by the if-structure | signalled by -s | a one-off event | |

| What would you do if she didn't arrive? | Future | Past | Simple |

| signalled by the if-structure | signalled by the auxiliary, did + n't + bare infinitive | a one-off event |

We can see from even this short list, that time, tense and aspect do not exist in a one-to-one relationship. Tenses are not, formally, tied to time and aspect is not always signalled by formal changes in the verb.

|

The starting point |

Before we can consider how English encodes notions of time,

we have to decide what sort of tense system it actually has.

This may not be a question many practising teachers ask but it

is important.

This site works from the premise that English has a very simple

tense inflexion system but a complex aspectual

tense system.

What do we mean by this?

Well, if, for example, we take the past tense of a verb in

English such as walk, we find that the only change we

have to make to the base form of the verb is to add -ed

to the verb and that gives us walked, of course.

If we form what we are pleased to call a simple future in

English, we simply add an auxiliary verb and arrive at will

walk. Those are the only changes we

make to simple aspects.

Even when we make a progressive form, we can see from what

follows that very small changes are required.

That means that the language is defective when we compare

it with two other reasonably closely related languages such as

French and German. Here's how it looks:

| Person | Past verb forms | Future verb forms | ||||

| Language | English | French | German | English | French | German |

| First singular | walked was/were walking |

marchais | ging | will walk will be walking |

marcherai | werde gehen |

| Second singular familiar | gingst | marcheras | wirst gehen | |||

| Second singular distanced | marchiez | gingen | marcherez | werden gehen | ||

| Third singular | marchait | ging | marchera | wird gehen | ||

| First plural | marchions | gingen | marcherons | werden gehen | ||

| Second plural familiar | marchiez | gingt | marcherez | werdet gehen | ||

| Second plural distanced | gingen | werden gehen | ||||

| Third plural | marchaient | marcheront | ||||

You can see that in the past in French, there are five possible

forms to choose from and in German, there are four. For the

future, for which French can inflect the verb itself, we have a

choice of six forms and in German, which also uses an auxiliary verb

for the tense, the verb of choice gives us five forms to choose

from.

Our choice depends on whether we are talking about first, second or

third person forms, whether we are being polite and distanced or

familiar and friendly or whether we are referring to plural or

singular subjects.

English does none of that and is wholly defective in this respect,

relying on a single form for all persons, all social relationships

and all numbers.

To complicate matters further, French also has an aspect system and

the verb forms above are just one of the possible selections because

French also uses the verb have [avoir] to form a

tense superficially similar to the English present perfect but which

does not signal the same kind of relationship to time at all.

The past tense forms in French set out above qualify for translation

into English as imperfective forms, akin to I was walking

rather than I walked. The same form is used,

incidentally, when English would employ the used to

formulation for past habits. When French forms the tense with

an auxiliary verb such as in:

J'ai marché

the translation would be I walked, not I have walked.

German, too, can form a tense in a similar way but that form, too,

does not carry the same aspectual considerations as the English form

does. It is quite arguable, in fact, that German does not have

an aspectual tense system at all. The German tense formed with

an auxiliary such as in:

Ich bin gegangen

can be translated either as I walked or I have walked.

Equally, as we see above, Standard German makes no distinction

between imperfective progressive events and perfective simple ones.

To some extent, too, both French and German are defective because

neither language distinguishes the verb forms for all

numbers, persons and social relationships. English, however,

is almost wholly defective.

The examples above are of other European Indo-European languages

which are closely related (comparatively) to English. Other

inflecting languages, such as the Slavic languages, other Romance

languages like Spanish and Portuguese and Greek exhibit the same

kinds of inflexions for person, social distance and number.

When we venture beyond this language grouping, things become even

more complex and distinct.

If you find yourself teaching an inflecting language, considerable

classroom time needs to be devoted to teaching and correcting the

inflected forms of tenses.

The moral in all this is that proceeding in English to focus on

form rather than meaning is not a sensible way to go. The

tense forms themselves can be taught in minutes, even when we form

aspects with the very irregular verb be.

The focus in teaching English has to be placed on meaning and for

that to succeed, aspect is the key.

To do that, of course, requires you to become something of an expert on aspect in general and to be able to identify what the aspects in English do in terms of communication of notions and perspectives. For that to happen, some common confusions need dispelling.

|

The confusion between progressive and continuous |

| I think they're talking nonsense |

It is unhelpful to assume that continuous and progressive are

simply alternative words for the same aspect (although many grammars

do). We may, somewhat

loosely, call the tense form something like present / past /

perfect etc. continuous but when we consider aspect, we need to be a little

more careful.

Nevertheless, it is true that in English little distinction in verb

forms is made between continuous and progressive aspects so, for

example:

John is working at his desk now

is progressive insofar as it refers to an action in progress, and

I am staying at The Ritz

is continuous insofar as it refers to a background state rather than

an action currently in progress (I may be nowhere near The Ritz at

the time of speaking).

As we shall shortly see, both these aspects can be realised through

apparently simple forms of the verb, although the

construction with the primary auxiliary be and the present

participle is the most common choice.

It is important that teachers of English are aware that other

people's languages may reserve explicit verb forms to distinguish

between progressive and continuous aspects. Other languages,

such as German, make no distinctions at all.

- Continuous aspect

- describes a current state of affairs such as, e.g.:

I believe in fairies

He loves me

He is loving the attention

He hated me

We are on holiday

She is living in a guest house

etc.

The clue is in the name – the aspect refers to the speaker's perception that something is a continuing state of affairs rather than a progressive or repeated action.

The continuous aspect does not always require the auxiliary + -ing. It can be inherent in both the simple form and the auxiliary + -ing forms of the verb. This is especially true, of course, with verbs such as think, believe, hate, understand, like etc. which contain the sense of the continuous semantically so do not exhibit any grammatical signalling of the continuous state.

Some of the examples above are simple tense forms but they nevertheless refer to a continuous state. - Progressive aspect

- describes an ongoing action such as

I'm typing this sentence

He runs the length of the field and scores

She is taking liberties

We were eating in my favourite restaurant

etc.

The clue is in the name – the aspect refers to the speaker's perception that something is, was or will be in progress, i.e., an ongoing action.

Notice, again, that the progressive aspect does not always require the auxiliary + -ing. It can be inherent in both the simple form and the auxiliary + -ing forms of the verb. For example

Look, I now turn over the paper and there is the shape

Here she comes!

I acknowledge receipt of your letter

all of which imply an ongoing action but none of which uses the auxiliary plus -ing form.

The simple form for a progressive action is, however, more rarely used than the simple form for a continuous state.

The -ing form of the verb can lead to some ambiguity

because it can signal both continuous and progressive aspects of the verb.

That is to say, it can signal a

background event which is perceived as taking place in the

present but is not necessarily something being done right this

minute or a progressive, ongoing action happening now.

For example:

She is studying French at university

could imply

that right this minute she is in a classroom or the library

actively studying but probably refers to a continuous background event. She may not, at the time of speaking, be

anywhere near the university in question. Compare this

meaning with:

She's in the garden, pulling up weeds

which, because of the nature of the act and the prepositional

phrase, almost certainly does refer to the present moment and is

progressive rather than continuous.

The same form can also signal repeated events when it is used

with a verb which cannot be conceived as progressive or

continuous such as knock in:

Someone is knocking at the door

which is not progressive or continuous but iterative in meaning.

See below under telicity for more on this.

|

The confusion between stative and dynamic |

| I'm thinking about it |

Much of the confusion evident in describing verbs as either stative or dynamic arises from the inability to distinguish between continuous and progressive aspects.

There is a distinction between, e.g.,

I am thinking

and

I think that ...

It is the distinction between the progressive aspect (I am

thinking) and the continuous aspect with a simple verb form (I

think). In the second of these, the verb is akin to believe (i.e., a

continuous state of mind) and

in the first, it describes an ongoing (that is to say progressing) action or process.

For this reason, if no other, it makes sense to speak of stative vs. dynamic uses of verbs.

Even verbs which do not refer to mental states may be used in

both senses so, for the picture above, for example, we might say:

She sat down on the bench (active use)

She sat on the bench for a while (stative use)

She suddenly sat on the bench (active use)

She was sitting on the bench (stative use)

She was just sitting on the bench when she remembered

what time it was (active use)

I saw her sit on the bench (active use)

I saw her sitting on the bench (either use depending

on the context)

Many other languages make no such distinctions between these uses of verbs and the expressions I go and I am going or I think and I am thinking are indistinguishable. English is not unique but it is slightly unusual. In particular, the use of progressive forms of tenses is often determined by a verb's stative or dynamic meaning (not its form). That is to say, the issue is semantic not grammatical.

Therefore, it is misleading and error-inducing to speak of stative or dynamic verbs (although many grammars use the terms as a shorthand). It does, on the other hand, make sense to consider the meaning of the verb in question and consider whether the use is stative or dynamic.

|

The confusions between perfective, imperfective and perfect |

There are three concepts here:

- Perfective

- is the term used to indicate that an event or state is

completed. For example,

Napoleon died in 1821

is a perfective form which may or may not have present relevance but is clearly finished.

I went to Margate last Thursday

is another example of a perfective form in English.

I have given up smoking

is also a perfective form (because the action is completed) which happens to be in the perfect aspect as well, in this case because it has direct relevance to the present. We are making a crucial distinction here between perfective events and perfect aspects.

The perfective can be contrasted with the ... - Imperfective

- which is the term that indicates an event is not completed.

Examples are:

She was playing tennis with John

I have lived here all my life

In neither case is the event perceived as finished. The form of the verb is described as imperfect.

Many languages, the European Romance languages among them, distinguish perfective and imperfective notions by alterations to the form of the verb. The past tense forms in French, set out above, qualify for translation into English as imperfective forms, as was explained there. - Perfect

- is the term used to signify an imperfective or perfective

state or event which

has a certain tense structure and carries a notion of the relativity

of two events.

For example,

I have been to America

is a perfective (the act of going to America has been completed) but is a perfect tense form indicating that the past event is set in the present (and, therefore, has present relevance of some sort).

I have lived here all my life

is imperfective (but still a perfect form) because it also signifies some present relevance (in this case that the state is probably (not certainly) current).

The perfect is, in English grammar, contrasted with the simple.

Many other languages, again, make no such distinctions between

these uses of verbs and the expressions I went and I

have been are indistinguishable. English is not unique

but it is slightly unusual.

Some languages are much clearer about perfective and imperfective

forms. For more on other languages, see

the guide to aspect.

|

Telicity: terminative, punctual and durative verbs |

This is a related phenomenon in languages.

The term telic comes from the Greek,

τέλος [telos], meaning end.

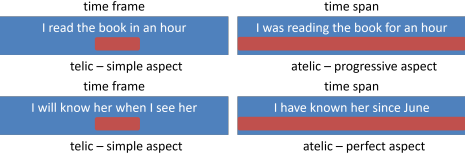

The concept of telic and atelic verb phrases concerns whether an

activity is seen as finished or unfinished. To grasp the

point, compare:

- I read the book for two hours

- I read the book in two hours

Sentence 1. suggests that I did not finished the book so

the verb phrase is atelic: no end is in sight.

Sentence 2. suggests that I finished the book so the verb

phrase is telic: the end point is clear.

This matters in English because we can say:

I was reading the book for

two hours

but we cannot have:

*I was reading the book in two hours.

The distinction here is between:

- a time span adverbial such as

for an hour

throughout the week

this year

which are all usable with progressive aspects of the verb so we allow:

She had been running for a while

They had been working throughout the weekend

I have seen her this year - a time frame adverbial such as:

in a minute

within a week

during the month

which are generally seen with a simple aspect of the verb so we allow:

She will arrive in a day or so

I will get it to you within a day or two

He crashed during the race

The implication for English grammar is that verbs in the

progressive aspect are almost always possible with a time

span

adverbial but not with a time

frame adverbial.

A time frame refers to a period of time within which an action

or event is set to finish but a time span is simply a period of time with

no indication of an end to an event.

In other

words, perfective forms, which are by definition telic, generally

imply a time frame (even when it is not stated) but not a time span.

For example:

- I had been reading for an hour

is possible because for an hour refers to the time span in which the reading occurred, but

*I had been reading in an hour

is not possible because in an hour refers to a time frame - I was cycling for a week

is acceptable because the adverbial refers to a time span

but

*I was cycling in a week

is not allowed because the adverbial indicates a time frame - I have lived here for a year

is allowable because the adverbial indicates a time span

but

*I have lived here in a year

is not allowed because the adverbial indicates a time frame - I was reading when the telephone rang

is allowed because the telephone call occurs within a time frame but the reading is set within a time span

but

*I read when the telephone rang

is not allowed because the reading is set within a time span.

The situation is complicated by the fact that verbs are generally telic or atelic depending on their meaning so the phenomenon of telicity is as much semantic as grammatical. For example:

- I finished the book in an hour

is telic by its meaning, because the adverbial refers to a time span, and - *I finished the book for an hour

is not possible because the adverbial refers to a time frame rather than a span. - I was cooking when the telephone rang

has the atelic verb cooking which is imperfective and the perfective rang which clearly had an end point so is telic. Compare: - I cursed when the telephone rang

in which both verbs are telic and perfective. - I strolled home in an hour

is telic because we can discern the end or goal of the activity but:

I strolled around the town in an hour

is not because stroll around is atelic in meaning so we need around for an hour.

If a diagram helps, it looks like this:

Some languages, for example Finnish, Estonian, Czech and Hungarian, reserve a special verb form to signal telicity but English often does it through tense aspects with and without adverbials.

|

A semantic issue |

In some languages (notably Russian) a distinction is made in

the form of the verb between those which are terminative and

those which are durative. English makes no such

distinction in form but the concepts account for some of the

stative / dynamic, perfective / imperfective and progressive /

simple tense forms that can be used. The use of the term

concepts here, of course, implies that we are

talking about meaning not grammar directly. In other words

the focus is semantic.

- Terminative verbs suggest either of two closely related

ideas

- a change of state which cannot, by its nature, be a

progressive or currently continuing event, for example

She struck the match

They opened the box

I sat down - an action which cannot continue because it is punctual

or momentary, for example

The glass broke

I wished her good morning

They slammed the door

- a change of state which cannot, by its nature, be a

progressive or currently continuing event, for example

- Durative verbs imply no such condition, for example

She sang at the party

I looked at the paper

I was working in the office

Most verbs are, in fact durative, or can be understood that way, and include drink, drive, eat, enjoy, live, play, sing, sleep, stay, talk, wear, work and hundreds more. See below for a list of examples of non-durative verbs.

When terminative verbs which imply a change of state are used in

progressive forms, they can be made durative so, for example, we can

distinguish the sentences above as:

She was peeling the potatoes

They were opening the box

I was sitting down

Terminative verbs which imply that an action cannot progress are

less often used in this way and cannot usually be made durative so

we do not usually encounter:

*The glass was breaking

*I was wishing her good morning

*I was glancing at the clock

When terminative verbs are used in the progressive aspect, the

implication is that the action was repeated. They are, in

other terms, iterative so the last example strongly implies:

I glanced at the clock repeatedly.

Durative verbs are commonly used in both the simple and progressive

forms to imply continuous or progressive states. For example:

I lived in London at that time

(continuous)

She stayed in a guest house on holiday (continuous)

They were studying at university then (progressive

or continuous, i.e., an action or a background

state)

He was running in the park (progressive)

Some terminative verbs can also be referred to as punctual or

momentary verbs because their meanings cannot allow a durative

interpretation. This is, therefore, a semantic

not a grammatical distinction.

These verbs include those which refer to instant events such as

arrive,

bang, begin, break, bump, burst, chop, crash, detonate, dip, dive, drop, explode,

flash, glow, hit, jolt, kick, light, meet, name, open, pop, quip, rap, shatter, shoot, slam, smash, spit, spurt, steal,

stop, tap, thump, upset, volunteer, wake

etc.

For example:

She is tapping on the window

cannot refer to a durative event because the verb itself is punctual

or momentary. The sentence can only be interpreted as

iterative in aspect because the action is being repeated.

One the other

hand:

She is playing squash with her brother

is durative (and possibly prospective) and implies a progressive

action rather than a momentary one.

Other examples include these pairs of sentences:

| Progressive | Iterative |

| The light is glowing | The light is flashing |

| She was aiming | She was shooting |

| The dog was growling | The dog was barking |

| The rain is falling | The rain is splashing |

Some verbs are interpretable either way depending on the co-text and

context so, for example:

I am sitting on the train to London

almost certainly means that the action is durative and current

(i.e., continuous) but:

I am taking the train to work these days

almost certainly means that the action is repeated (i.e., iterative)

and the adverbial, these days, reinforces that sense.

Verbs such as steal also live on the borders between

punctual and durative meanings so they can work as punctual and as

durative verbs depending on the context. For example, we can

have:

He's stolen my pen

which is clearly a momentary event so

He's been stealing my pen

makes little sense unless one believes that a pen can be stolen

multiple times. Make it plural (pens) and it works:

He's been stealing my pens

clearly relates to an iterated event.

On the other hand,

Someone's been stealing vegetables from my

garden

is a possible punctual verb used iteratively.

The verb work shares this characteristic. so, for example:

I've been working too much recently

strongly implies a series of working days rather than a single

event.

All the speaking verbs, say, speak, talk and tell,

work this way, too.

|

An example of telicity and punctual vs. durative verbs in action |

| knock, knock |

To get this distinction really clear, you need to get the

difference between the word continuous and the word

continual. The first refers to an unbroken state so, for

example:

The car makes a continuous growling noise

means that the noise is not interrupted but

The car makes a continual growling noise

means that the noise comes and goes.

So, continuous means constant and continual

means often repeated.

We'll take the examples of the punctual verb, knock. and

a durative verb wear. The first is a punctual verb

because, by definition, the action is momentary and

cannot be extended but it can be repeated. The second is

durative because, by definition, the action

continues for some time.

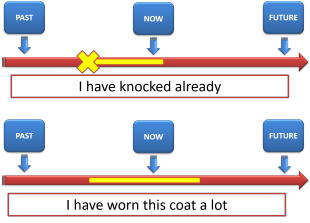

So, if we say, e.g.:

I knocked

we are clearly using the verb telically because we perceive that the

action is completed (so it's also perfective). Equally, if we

say:

I have knocked already

we know that this is a present tense message implying something

like:

So there's no need to knock again

or whatever and here, too, the meaning is perfective and telic

because, by definition, the verb cannot be durative. The verb

is also telic, of course, because by its nature the action had an

obvious end point in time.

A durative verb such as wear sends a very different message

because:

I have worn this coat a lot

can be interpreted as meaning that I am wearing it now so is

durative in meaning extending from the past into the present and the

immediate future. In other words, the verb is atelic because

no end point is recognisable to the hearer.

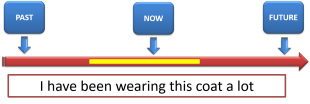

The time lines look like this:

in which the first one shows the current effect of the action and

the second shows the durative nature of the verb wear.

In both cases, the yellow line is deliberately extended into the

immediate future as well as the present because this perfect tense

in English refers to the present in relation to the past, not the

other way round. That's why it's called the present

perfect, of course.

Now, if we say:

I have been wearing this coat a lot

we are not, fundamentally, changing the meaning which is signalled.

The time line will still be the same, to wit:

and all we are doing is emphasising the duration of the verb.

That's not all it does because the use of a progressive also makes

the idea of the action continuing into the future more emphatic.

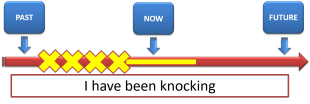

However, if we try the same trick with the verb knock,

we cannot use the same time line because:

I have been knocking

must be represented with something like:

in which it is clear that the use of a progressive form of a

punctual verb results in an iterative aspect. It also implies

quite strongly that the knocking will go on.

In other words:

Simple use of a punctual verb = telic

and perfective.

Progressive use of a punctual verb = atelic, imperfective and

iterative.

Simple and progressive uses of durative verbs = atelic and

imperfective.

If we want to signal an iterative aspect of a durative verb, the

simple form + an adverbial (such as again and again, repeatedly,

frequently, repetitively, continually, time after time etc.) is

the only choice so we allow, e.g.:

I have worn this coat again and again

However, we cannot signal iterative uses of a durative verb using

the progressive form because:

*I have been wearing this coat again and

again

is not allowed (in English) although:

I have been wearing this coat all year

means continuously, not continually

(i.e. constantly, not repeatedly) so is fine.

With punctual verbs the case is altered because both:

I have been knocking again and again

I have knocked again and again

are both allowed although the use of the adverbial in the first case

is unnecessary and the second form is slightly odd because English

speakers would usually keep it simple and select the progressive

form without the adverbial to convey the message.

English, of course, does not distinguish these senses

structurally (although it often uses adverbials, as we see, to make

the sense clear) but other languages sometimes do change the form to

distinguish the meanings. This is, of course a source of error

for learners who may choose:

I was hitting it with a hammer

when no iterative sense is intended. This type of covert error

is quite common.

The moral is that this matters in the classroom because if we try to

teach tense forms without considering what sort of verb we are

using, people will get confused and things wrong.

The distinction can be shows by presenting two different images

like, e.g.:

|

|

| He was hitting it with a hammer | He hit it with a hammer |

In the guides which are linked from here to present and past time, some attention to durative and punctual verbs will be given, especially in the guide to talking about the past because that is where the distinction is often important.

There is also a guide on this site to lexicogrammar, which considers how the meaning of the lexis we use determines and sometime subverts the syntax (new tab).

|

Relative and absolute tense forms |

Here, we depart slightly from a traditional description of tense forms in English and take a more functional view of what the forms actually do and the meanings they realise.

- Absolute tense forms

- These locate an event in time relative to the here and now,

i.e., the time of speaking or writing. For example:

She will take the 6 o'clock train

sets her action as lying in the future from now.

She caught the 6 o'clock train

sets her action in the past seen from now

She is getting on the 6 o'clock train

sets her action in the present or the present concerning a future arrangement

She was sitting on the train

sets the continuous state in the past

She will be sitting on the train

sets the continuous state in the future - Relative / relational tense forms

- These take it a step further and relate what is happening

relative to an absolute tense. For example:

She has caught the train and is working on her laptop

sets the present (working) in relation to a past event (getting on the train). In other words, it embeds the past in the present. The present has been altered by a past event because the implication is that she could not be working on her laptop had she missed the train.

She had caught the train and was working on her laptop

sets the past (working) in relation to the pre-past (getting on the train). In other words, it embeds the pre-past in the past.

She will have finished by the time the train gets to London

sets the future (finishing) in relation to the post-future (getting to London). In other words, it embeds the future in the post-future.

Relational tense forms do not stop there. For example:

She was sitting on the train, reading a book

is absolute in the sense that the events are fixed in time relative to the present as we saw above.

However,

She was sitting on the train when she realised her mistake

sets the realising in relation to a background event and

She had been going to work but had forgotten her laptop

sets the working as a future in the past (although one that did not happen).

An alternative way of seeing these forms is to consider what is being expressed in terms of time and the relationships between events and states, like this (following Lock, 1996: 149):

| Time | Example | Explanation of the concept | Visualised green for present orange for past blue for future |

| The present in the present | He is working in the garden | The verb form refers to now set relative to now |

|

| The past in the present | He has worked in the garden | The verb form refers to pre-now in relation to now |

|

| The present in the past | He was working in the garden | The verb form refers to the present set in the past |

|

| The past in the past | He had worked in the garden | The verb form refers to the pre-past set in the past |

|

| The present in the future | He will be working in the garden | The verb form refers to the present set in the future |

|

| The past in the future | He will have worked in the garden | The verb form refers to the past set in the future |

|

| The future in the present | He is going to work in the garden | The verb form refers to the future set in the present |

|

| The future in the past | He was going to work in the garden | The verb form refers to the future set in the past |

|

Seen this way, complex tenses which combine aspects can be explained conceptually.

The visualisation in colour on the right of these tables appeals to some learners. Do not present them all at once!

The page of example timelines to demonstrate some of the relationships set out here may help if you are considering teaching from this standpoint. Click here to go there (new tab).

|

Finite and non-finite forms |

In these guides, we are mostly concerned with finite verbs forms

(i.e., those marked in some way for person or tense). There is

a guide to

finite and non-finite forms on this site.

It should not be forgotten that non-finite forms can also signal

aspect, even if they do not signal time or tense. For example:

| Forms | Meaning | Aspects |

| Feeling rather shy, he put his hand up | At the time he felt shy and at the

time he put up his hand: two processes, one continuous (the feeling) which is non-finite and one instant (the action) which is finite |

continuous and simple |

| Being rather a tall man, he reached it easily | Two verbs, one a permanent state (tall) which is non-finite , the other an action (instantaneous) which is finite | continuous and simple |

| Arriving at station, he realised he was late | Two simple actions (arriving and realised), the first non-finite and the second finite | simple |

| If you will just hear me out | Two verbs (one apparently future but actually present and referring to willingness) and finite, the other an infinitive (non-finite) | simple |

|

Moving on |

If the distinctions above are clear to you, it's time to look at the ways English refers to time and the speakers' perceptions of time.

To check that you have taken this on board,

try two tests.

If you would like a terminology matching task, there is one

here.

|

Guides to times, tenses and aspectsIn what follows this site takes a somewhat alternative view of tense grammar. |

|

Wrong way round #1 |

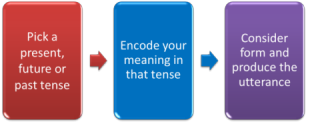

Many grammars, especially those aimed at students, start with the name of the tense, explain its formation and then list the ways in which it is used and the meanings we make with the forms. It works along the lines of, e.g.:

The present progressive is formed by

taking the appropriate present tense form of the verb to be, and

following it with the -ing form of the verb (omitting a

final 'e' if it is present) so we get, He is having lunch with

his mother.

We use this tense to talk about current

actions in progress, temporary states, the arranged future and ... etc.

That is familiar to most learners and teachers and may be

reassuring. However, it is a non-functional way to proceed.

It is non-functional because it presumes a mental process something

like this:

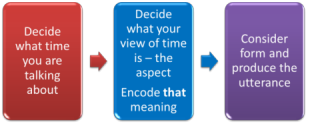

Here, we are going to work the other way: we will start with the

meanings we want to make and identify the major ways to make these

meanings using verb forms and their aspects.

This assumes a mental process more like:

In these guides, the assumption is that you know (and can teach) how the tenses

and aspects are formed because, as we saw above, English has a very

simple set of inflexions and frequently none at all.

We are only considering meaning and

function.

|

Wrong way round #2 |

The second way in which what follows may be different from

what you have read or seen elsewhere on the web is that we also

try to get the thought processes the right way round when it

comes to choosing adverbials to express aspectual meanings.

Here's an example, from the web, of getting things the wrong way

around when referring to the uses of the simple past tense in

English:

with for – to express the duration of

something in the past

They lived in Hong Kong for 8 years.

We waited for 2 hours for our train.

The reason this is the wrong way around and misleading is threefold:

- Only some verbs can be used in this sense of a durative

aspect with the past simple form and those are, as was explained

above durative verbs like live, stay, wait and so on which imply

long-lasting events or actions

We cannot use this form with punctual verbs such as light, hit, open etc. because that gives us:

We lit the fire then

We hit the drum then

She opened the parcel then

all of which imply a simple, short, finished action.

To make them signal a durative event, we are forced to use a progressive tense form as in:

We were lighting the fire then

We can, however, form, for example:

They lived in Paris then

and imply a durative aspect because the verb itself carries that sense and cannot refer to a simple, short, finished action. - This has nothing at all to do with the prepositional phrase with for. It may be appropriate in some senses to add for two hours / years / months etc. but that is not a determiner of the tense form to use. We do not start by selecting a prepositional phrase and then select a tense form to match it.

- In any case, confining the form to the preposition for

is both misleading and prescriptive and almost bound to lead to

a teacher-induced error. There is a wide range of other

adverbials which it may be appropriate (or not) to use with this

aspect of the verb and they will include, e.g.:

at that time

when she was a child

in the 1950s

and hundreds more.

Here's the list. Click on the area that interests you.

| Talking about the Present | Talking about the Past | Talking about the Future | Talking about Always | Teaching tense and aspect |

Reference:

Lock, G, 1996, Functional English Grammar, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press