Lexicogrammar: the interface

There is a noticeable tendency in language teaching to treat

meaning and structure as if they were self-contained areas of

knowledge about language.

It is, however, fairly clear that, for example, the distinction

between these two sets of sentences:

- I am feeling ill

- I feel ill

- I am living in Paris

- I live in Paris

is not simply one of whether the speaker chooses to use a

progressive aspect of the verb.

Sentences 1. and 2. are, for most purposes, synonymous and it makes

little difference whether the speaker chooses to use the verb

dynamically, as in 1., or statively, as in 2.

However, sentences 3. and 4. are different in meaning as well as

structure. Sentence 3. implies a temporary condition but

sentence 4. implies a permanent one.

The essence of the difference lies not in the grammar, which is

common to both pairs, but in the meanings of the verbs.

Put another way, the grammar and the meaning of words are not

separate systems treatable as discrete units but are interdependent.

That, roughly speaking, was what Halliday meant when he coined the

term lexicogrammar to describe the language system. In his

words:

grammar and vocabulary are not different

strata; they are the two poles of a single continuum, properly

called lexicogrammar

Halliday / Matthiessen (2014: 24)

This guide is a short one, focusing on some obvious but important examples of times in which it is unwise to treat the systems of the language as if they were either grammar or lexis (i.e., structure or meaning carrying items) but to consider both systems together. Before we do that, it is necessary to take a short diversion into understanding our terms.

|

Syntax and lexis |

If we choose to separate the systems for the sake of argument, we

can, of course do so and consider syntax as separate from paradigm.

There are two types of relationship at work here:

- Syntagmatic relationship

- This describes the relationship which work horizontally between words. Subjects use Verbs, Verbs sometimes take Objects, Adjectives modify Nouns, Adverbs modify Verbs and so on. The relationship is to do with syntax (from the Greek meaning to arrange together).

- Paradigmatic relationships

- Relationships work vertically in the sense that Noun

phrases can be replaced by other Noun phrases, Verb phrases by other

Verb phrases, Adjectives by other Adjectives, Adverbs by other

Adverbs and so on. The relationship is to do with word

and phrase class. The word paradigmatic derives from

paradigm (from the Greek meaning to show

side by side).

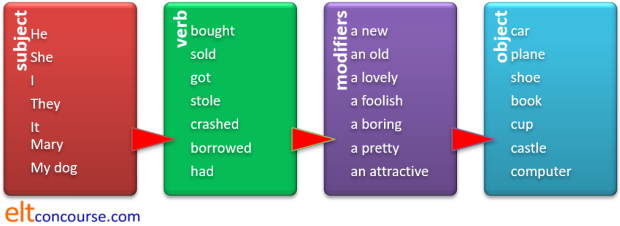

It works like this:

Each slot in the sentence can be replaced by words and phrases in the same classes to make new sentences (some of which might make sense) virtually ad infinitum. The boxes give examples of items in a paradigmatic relationship; the red arrows show the syntagmatic relationships.

For many purposes in the classroom, it makes some sense to analyse language this way and separate out considerations of syntax from considerations of lexical relationships and word and phrase class.

However, the purpose of this guide is to explain why syntactical

arrangements alone do not explain the systems of a language and

lexical relationships alone also cannot do so.

In order to do that, we'll take some examples of where the interface

between grammar and meaning provides some insights.

|

Oh, that's just an exception |

There is a temptation, worth avoiding in the classroom, to

suggest that anything which appears to break a syntactical rule

qualifies as an exception and needs to be learnt separately.

So, for example, we might suggest that a syntactical rule is

exemplified by allowing, e.g.:

She walked to work

but forbidding

*She walked the way to work

and stating that the rule is that this verb is, in English,

intransitive. So far, so good and so simple. However,

when learners then encounter:

We walked the dogs

I walked her to the door

I walked an hour

They walked three miles

it is not terribly helpful to tell them that these are merely

exceptions to the rule. What we have, in fact, is an example

of something which happens frequently in all languages:

meaning has altered what is syntactically possible.

What has happened is that our syntactical rule has been refined to

take semantic issues into account and is now:

- When walk means go on foot it is intransitive.

- When walk means exercise or take for a short journey on foot it is transitive.

- When walk mean accompany, it is transitive.

- The verb can be used with distances and times as direct objects.

and the issue is solved by appealing to meaning, not syntax.

Exemplification follows of some of the key areas in English where semantic considerations work with (not against) syntactical issues to refine the rules of usage.

|

The article system |

A particular source of confusion for learners from many language

backgrounds is the article system in English which compels speakers

to consider a range of factors which they may not have to think

about in their own languages including specificity, definiteness and

countability before deciding on the correct article to use. We

get from these considerations a rule which states that abstract

ideas take a zero article (Ø) because the reference is non-specific,

non-definite and uncountable. Thus it is that we can have:

I don't approve of prejudice

She was in danger

and not

*I don't approve of a prejudice

*She was in a danger

or

*I don't approve of the prejudice

*She was in the danger

and all works well until we encounter, e.g.:

The prejudice against women is unacceptable

A prejudice he still has is to assume all politicians are

lying

There is a danger of it breaking

The danger is clear

which appear to break the rule and must, therefore, be treated

as exceptions and separately learned.

A little thought, however, reveals that the issue is not

syntactical, it is semantic. Many mass nouns describing

abstract concepts can:

- be used both as mass nouns and as count nouns so we get,

e.g.:

The friendships she has are important to her

The sorrows of the family were many

It is a pet hate of mine

and so on. - be modified to move the concept from a generic, non-specific

meaning to a definite and specific reference so we can also

have:

He is one of the loves of her life

Dinner was a real delight

The dangers inherent in the process are clear

(This small semantic issue also explains, incidentally, why we have:

The United States

and not

*The America)

No rule is being broken in these cases because the meaning of the nouns has altered to allow the general syntactical rules for article use to be followed.

The alternative to labelling some uses of the article system in

English as exceptions to the rules is to invent an unnecessary rule

to explain certain uses. We get, then:

She bought a new flat. The flat was on

the second floor.

explained by the invention of the known-unknown rule which

states that the unknown instance is preceded by the indefinite

article and a known reference by the definite article.

However, semantic considerations can be used to make this clear

without enjoining learners to acquire a new rule.

When the reference is indefinite but specific, the use of the

indefinite article is customary so we can explain:

A man called while you were out

and

A letter has arrived for you

by invoking the meaning intended that I know what

sort of thing I am referring to (so references are specific to

man and letter) but not exactly which

thing is in question (so the references are indefinite).

When the reference is to something both specific and

definite, the rule is to use the definite article (because we know

both what it is and which it is). This explains:

The bathroom is upstairs

because we know we are referring to a specific and definite

room. Of course, if we said:

A bathroom is upstairs

it would be clear that we are now referring to one bathroom

from a possible number of them and that would be specific reference

to a bathroom but indefinite reference to which bathroom and no rule

is broken.

If we apply that rule to the first example, it is clear that the

first reference to flat is specific (we know what it is)

but indefinite (we don't know which it is). The second

reference is, because of the meaning, not the

grammar, to something which is both specific (we know what it is)

and definite (we now know which it is: her new flat) so we

follow the usual rule and use the definite article for specific,

definite reference. The issue is, therefore, solved by

applying the rules and considering the meaning of

what is said rather than by inventing a new rule to explain it.

The guide to the article system in English, linked below, contains more consideration of semantic issues which, when ignored, lead to the invention of new rules and the invocation of exceptionality to explain what is actually a tightly rule-bound, lexicogrammatical system albeit one profoundly affected by meaning.

|

The passive voice |

The system explained above is the traditional way of viewing the systems of a language

and in many cases it does make sense to separate them and teach,

say, the formation of passive-voice clauses as if it

were possible to analyse them without reference to the words and

meanings embedded in them.

Therefore, we can, taking a purely syntactical approach suggest

that:

The man drove the car

and

The car was driven by the man

describe the same proposition.

It's a short step from there to stating a rule that an active-voice

clause with a transitive verb taking a single object can be

transformed into a passive-voice equivalent.

Thus, it follows that we can present learners with, for example:

| Active | → | Passive |

| The children broke the plates | → | The plates were broken by the children |

| The car damaged the fence | → | The fence was damaged by the car |

| She will do the work | → | The work will be done by her |

and so on, quite literally, ad infinitum.

However, if we take that approach, we will soon run into trouble and

be forced to explain that although something like:

Her daughter resembles her

is a well-formed active-voice clause with a discernible subject, a

transitive verb and an object as one would expect, so we can,

following the rules of syntax make:

*She is resembled by her daughter

and arrive at a perfectly formed (and just about understandable) clause

which is nevertheless disallowed in English. The reason it is

disallowed is not that it is a syntactical or grammatical exception,

it is to do with the meaning of the verb itself.

What we have to do is look at the meaning of transitive verbs and

the relationships they have to their objects.

Here's what is meant:

Most transitive verbs imply that the subject of the clause is acting

on the object and so it is that we can make acceptable passive forms

from, for example:

John kicked the ball → The ball was

kicked

Mary told a joke → The joke was told

The storm damaged the house → The house was damaged

and thousands more clauses containing transitive verbs in which the

object is altered or acted on by the subject.

However, if we consider, for example:

She has a lot of money

They possess four houses

The chair lacks a leg

The tank contains 45 litres

The bottle holds a gallon

This shirt fits me

The boy took after his father

then it is clear that the subject of the verb is not acting on

the object in the same way that the subjects act in the first set of

three examples.

What these verbs do is express a relationship between the subject

and the object rather than signalling that the object is affected,

changed or acted on by the subject and that is the reason that they

do not form passive clauses. We cannot have:

*A lot of money is had by her

*Four houses are possessed by them

*A leg is lacked by the chair

and so on.

So our rule for how to form the passive in English has to be revised

to include the meanings of the verbs, not just their syntactical

relationships with other elements in the clause.

|

Relative pronoun clauses |

Relative pronoun clauses might, at first sight, be the subject of

syntactical issues alone because considerations of whether or not

that can be used, whether or not the pronoun may be omitted

and whether or not the clause can be reduced by ellipting the

pronoun and the verb seem to be solely syntactical issues to do with

case and tense forms.

They are, however, also subject to issues to do with the language

user's intentions and the meanings which are expressed in a number

of ways:

- English distinguishes between defining and non-defining (or

restrictive and non-restrictive or identifying or

non-identifying, as you prefer) relative clauses and the type of

clause has a syntactical effect on how they may be constructed

(with or without the ellipsis of the pronoun or allowing the use

of that etc.).

However, the choice of clause type is not defined grammatically, it is determined by the meaning that the language signals.

We cannot allow:

*The United States President who is here at the moment will speak later

because we cannot define that which is unique so, in English (but not in other languages for the most part), we have to select a non-defining structure and mark it by punctuation or tone group prosody allowing only:

The United States President, || who is here at the moment, || will speak later.

In other words, the nature of the subject of the clauses determines the type of clause we are allowed and that is a meaning issue. Any uniquely identifiable subject is disallowed in a defining relative clause and that will include people (identified by name or position), places (identified by name, such as France, Germany, Asia, Mars etc.) and so on.

Therefore, we cannot allow, for example:

*Germany which is the richest country in Europe || is much admired

or

*Number 10 Downing Street which is in the centre of London || is well known

and can only have:

Germany, || which is the richest country in Europe, || is much admired

or

Number 10 Downing Street, || which is in the centre of London || is well known

The effect of this is to allow a certain ambiguity (another meaning rather than syntactical issue) to creep in so we may encounter, for example:

The president of the company that is very successful

which could refer to a successful company or a successful president and has to be disambiguated by selecting the appropriate pronoun rather than that and having either:

The president of the company which is very successful

or

The president of the company who is very successful

and that is how the meaning the speaker wishes to signal determines the syntax. - The choice of pronoun in English is heavily dependent on

both the type of noun referent and the case of that noun.

That is to say, issues of both meaning

and syntactical role are in play.

We find, obviously, that who and whom are used to refer to people and the latter is accusative only. There are, however, some more subtle relationships to do with the meaning of the referent that are seen:- The pronoun which may be applied to people but

only if the person in question is unknown to the speaker so

we can allow:

The police officer which arrested her made his report

but we do not allow

*My local police officer which arrested her made his report

and the difference is purely to do with the relationship between the speaker and the subject of the clauses. - Similarly, the pronouns which

and who(m) may both be applied to collectives of

people so we can allow both:

That's the committee which decided

and

That's the committee who decided

and the choice will often depend on how well the people in the group are known to the speaker.

However, immediately, there is a knock-on syntactical effect because, in BrE at least, the verb and pronoun concord will be altered so we get:

That's the committee which decided the issue and it presents its report later

vs.:

That's the committee who decided and they present their report later

and that is an example of meaning altering syntax rather than syntax being determined by grammatical relationships alone. - An allied issue is that the pronoun who can be

used to refer to some higher animals but only to ones with

which we are acquainted so we can state:

My dog, who hardly barks at all, is a much loved family pet

but we cannot state:

*A dog, who barked all night, lives somewhere close, I think

and we are forced to select which or that as the pronoun.

- The pronoun which may be applied to people but

only if the person in question is unknown to the speaker so

we can allow:

- We can reduce a relative clause from, for example:

He lives in the house which was built by his brother

to

He lives in the house built by his brother

without recourse to worrying about the meaning because this is a syntactical issue subject to discernible structural rules which can be set out in a paragraph or two (as is done in the guide to the area, linked below).

There are, however, two issues to do with meaning which come into play to determine whether a reduced clause is permissible (or to be recommended):- Time and tense:

We cannot reduce a sentence such as

He lives in the house which has been built by his brother

to

He lives in the house built by his brother

because we lose the perfect aspect of the verb and send a different signal.

We can also not reduce:

He is going to live in the house which will have been built by his brother

to

He is going to live in the house built by his brother

because the sense of the proposition is not maintained and the second sentences implies that the house is already completed but the first makes it clear that it is not. - The nature of the subject:

If the subject of both clauses is the same, i.e., they are co-referential, then only a non-defining clause can be used so while we can allow:

The woman who is a gardening expert will be here later to help

in which we define the woman, as one among many, we cannot reduce that to:

*The women a gardening expert will be here later to help

because we know that the woman and a gardening expert are the same entity and we cannot define the same thing twice. We have, therefore, to make the clause non-defining and only allow:

The woman, a gardening expert, will be here later to help

Issues of co-reference are to do with meaning, not syntax.

- Time and tense:

All of these issues (and more are considered in the full guide to the area) are to do with the meaning we wish to achieve and are not, fundamentally, syntactical issues at all.

|

Adjuncts |

Part of the definition of an adjunct is that it is extra

information, often concerning the verb phrase, which is not essential to the clause and

can be safely omitted without damaging the syntax and acceptability

of the clause.

We get, therefore:

She left in the morning

That day, she left

He walked over the hill and down the lane to my house to see

me

and in all of those we have adverbial adjuncts adding information to the verb

phrase which can be omitted (albeit, of course, with a loss of

information) so we can equally have:

She left

He walked

and, because the verbs are intransitive, a two-word clause is well formed.

The same effect will work with transitive verbs although the object

must be retained unless they are ambivalent (like, e.g., eat):

She painted the house yesterday in the

sunshine

They opened the box very carefully and slowly to see what it

contained

Last week he timetabled the meeting later than usual to allow

people to arrive

and they can all be well-formed without the adjuncts as:

She painted the house

They opened the box

He timetabled the meeting

although, again, information is lost.

However, if we try this trick with some other verbs which have a

different sort of meaning, we encounter a problem. To see what

it is, try removing the prepositional phrases from:

He put the box in the corner

He placed the lamp in the corner

He rested the rock on the edge of the wall

We ventured further into the cave

She stayed in a hotel by the river

and then we get the unacceptable:

*He put the box

*He placed the lamp

*He rested the rock

*We ventured

*She stayed (unless the meaning is remain

rather than reside)

and there is, now, a need to consider meaning as well as syntax

to get to the root of the issue.

Again, as we saw with the formation of passive clauses it is the

relationship which the verb signals that matters.

If, as in these examples, the verb expresses a sense of positioning

something (either oneself or another entity), then the place adjunct

is compulsory, not optional.

Verbs that do this include keep, lay, place, plonk, position,

put, rest, set, site, situate, stick, stuff.

and they are described as PP complement verbs.

The issue is, of course, semantic, not syntactical and to get the

structure right, we have to know that the prepositional phrases are

not adjuncts at all and that is a matter determined by the meanings

of the verbs.

PP complement verbs are, therefore, not exceptions to the rules, they are part of the rules.

|

Tense and aspect |

A good example of the relationship between meaning and structure concerns the use in English of the perfect aspect of the verb combined with a progressive form as in, for example:

- She has been working really hard recently and needs a break

- They had been waiting for the train for hours and were frozen stiff

and in both cases, we can see that the effect of the aspects is twofold:

- The progressive form emphasises the

duration of the event

and - The perfect form serves to embed one event in a second event which it alters or enables in some way

Despite the fact that many languages do not do this kind of thing

at all, the sense of the aspects in English is learnable and

teachable.

However, again, when we use different verbs which carry different

sorts of meaning, it becomes clear that there's a problem with

simple explanations. Consider:

- Someone has been stealing vegetables from my garden

- She had been switching the heating off and on and the house got colder

Although the structures (i.e., the syntax) of sentences 1. and a. and 2. and b. are parallel, it is clear that the meaning is not.

The issue here is to do with what are called punctual or

momentary and durative verb senses.

Some verbs, such as live, work, stay,

study, read and a host more can be perceived as taking

up a time frame of some measurable length. For this reason, we

allow:

She has been living here for years

She has been working on the problem this week

I have been staying at The Ritz

They had been studying French at university

I had been reading Goethe lately

Other verbs cannot be used in the same sense and so the aspect which

the syntax of the verb phrase signals is very different:

He has been hitting it with a hammer

They have been arriving late most mornings

The light had been flashing

She has been tapping at the laptop keys

I had been upsetting my neighbours by parking there

and in all these cases, the sense is not of a progressive

action, it is of a repeated or iterative action.

Certain verbs, referred to as telic (i.e., starting and finishing

almost simultaneously) in sense, cannot successfully be used with

progressive aspects at all because they produce rare or odd forms

such as:

*They were popping the champagne cork

*"That's my little success," he was quipping

and so on.

To be clear, this is not a distinction between stative and

dynamic uses of the verbs (that comes next), it is dependent on the

meaning of the verbs alone.

Punctual verbs, for your reference, include at least: arrive,

bang, begin, break, bump, burst, chop, crash, detonate, dip, dive,

drop, explode, flash, glow, hit, jolt, kick, light, meet, name,

open, pop, quip, rap, shatter, shoot, slam, smash, spit, spurt,

steal, stop, tap, thump, upset, volunteer, wake.

With those verbs, a progressive form signals a repeated short

action, not a durative one. In some cases, moreover, an action

cannot be repeated at all (they are telic in the real sense) and the

progressive form is, therefore, not even allowed so for example:

*I had been waking my sister

*They have been naming their child

*When I dropped it, the glass was shattering

*The bomb was detonating

are all malformed, not because they are syntactically flawed but

because they are semantically flawed.

Again, the meanings of the verbs do not lead to exceptions to the aspect rules of English, they are part of the rules.

|

Stative and dynamic use |

It is often averred that some verbs are always used statively and others in a dynamic sense so we get lists such as:

- Verbs of possession or relations between things

be, appear, consist, contain, cost, have, depend, fit, include, involve, matter, mean, measure, owe, own, possess, seem, weigh - Verbs of sensations

feel, hear, look, see, smell, sound, taste, touch - Verbs referring to emotional states

adore, appreciate, care, desire, dislike, hate, hope, like, love, mind, need, prefer, value, want, wish - Verbs referring to mental processes and states

agree, astonish, believe, concern, deny, disagree, doubt, expect, flabbergast, forget, imagine, impress, know, please, promise, realise, recognise, remember, satisfy, suppose, surprise, think, understand

There is no denying that many of these

verbs do occur much more frequently in simple tense forms than in

progressive ones. On the other hand, a few, such as

measure, are actually more frequently used dynamically.

Of the others, most are used both statively and dynamically with,

often, a shift in meaning and syntax is not independent of meaning.

Almost all these so-called stative verbs can be used dynamically and

it all depends on what the user of the language means and we can

take examples from the same four categories to show this:

- She is appearing in the play

They are having trouble with their son - She is not feeling well

The engine's sounding a bit rough - She was hoping for better weather

They are wishing her happy birthday later - She is denying all charges

I was forgetting all about the need to book a table

It is, in other words, rare to discover a verb in the lists above

which cannot be used dynamically and all of them take progressive

forms in non-finite clauses so we routinely allow:

Containing only four grams, the bottle is

tiny

Depending how he feels, he'll be here later, I expect

Seeing everyone's already here, let's start

Tasting the soup again, the chef pronounced it ready

Caring little for long walks, I stayed at home

Needing some supplies, we went to the supermarket

Realising the danger, they backed away from the edge

Understanding his difficulty, we didn't press the matter

It is probably clear by now that simply labelling verbs as stative or dynamic is an inadequate and potentially harmful approach to take because it ignores meaning.

|

Adjectives |

| two old friends |

When asked for a rule of thumb to explain what adjectives do in

English it is simple to say something like they describe or

modify a following or preceding noun or noun phrase

and that works well until we encounter times when they don't

(really).

By some estimates, around 40,000 words in English qualify as

adjectives and the majority of them are unproblematic for learners.

If you are reading this somewhat esoteric guide, you will probably

be aware that we can say:

The woman was young

and

She was a young woman

and there is little to tell between those two propositions so most

adjectives can be used predicatively or attributively (as they are

respectively in these examples).

If we leave it at that, we have a reasonably good rule for the

syntax of adjective use which will hold up well for thousands of

adjectives.

However, the in-service guide to adjectives on this site is a long

one and that betrays the fact that all is not so simple.

|

Inherent vs. non-inherent uses |

While it is possible to say, for example:

My friend is old

which will mean that he or she is somewhat advanced in years, when

we use the adjective attributively as in:

She's an old friend

we are confronted by the fact that the adjective now describes the

friendship rather than the friend. The fact that the word

friendship does not appear in the clause at all is somewhat

confusing if we are taking a purely grammatical approach and

focusing on word order and syntax.

We have, therefore, to take a semantic tool to the mechanism and see

why this is happening. To do that, we have to consider what is

an alienable or inalienable characteristics of the noun we are

considering. That is to say, are the characteristics we wish

to describe related to the noun or part of the noun itself?

For example, if we say:

That woman is small

we are referring to an inalienable, inherent quality of the woman and we can

also phrase that as:

She is a small woman

so both types of syntax are available to us.

Another way of saying this is that the characteristic of smallness

is inherent in the noun and in neither case is the woman's size

subject to her or anyone else's will.

However, when it comes to alienable qualities, the case is

altered so if we say:

She is a small businesswoman

using the adjective predicatively, we find that the reference now is

to the type of business the woman runs rather than the woman

herself.

Even attributively with:

The small businesswoman at the back asked a question

we are constrained to understand that it is the business to which

the adjective refers, although attributive use can produce some

ambiguity.

The rule, such as it is, is semantic not syntactical and, briefly states:

Any adjective which cannot apply to a relationship will automatically be understood as referring to an inherent property of the noun

That means, for example

My friend is tall

can only be applied to the person because tall cannot be

used (because of its meaning) to modify a relationship.

Other adjectives which have to be considered semantically rather

than syntactically include: close, long-standing, nodding, good, intimate,

distant, old, bitter, devoted, great and more.

So, for example:

They are bitter enemies

will be seen to apply to the

enmity not the people

She's a distant cousin

will be seen to apply to the

kinship not the person

She's a long-standing member of staff

will be seen to apply to the employment, not to the person

and so on.

Another semantic issue concerns the adjectives new, old,

young and elderly which can be variably applied

depending on the intended meaning and no syntactical rule is

available to help us out so:

She's a new colleague

will be taken to refer to the relationship not the person, but

She's a young colleague

will be taken to refer to the person not the relationship, and

He's an old friend

can only refer to the relationship, but:

He's an elderly friend

can only refer to the person.

This is not, lest we get carried away into the stratosphere of a lexical approach, a question of collocation. It is an issue with meaning.

|

Dynamic vs. stative use |

While we can have, as we saw above, both:

She's a young girl

and

The girl is young

further semantic issues arise from the meaning of the adjectives we

use and the message we want to send.

If we wish to imply that the characteristic is under the control

of the person (or thing) in question then we are forced to employ

the predicative word ordering. We get, therefore:

The police officer was patient

and that strongly implies that she may have become impatient at any

moment.

However, if we say:

The patient police officer talked to the men

the implication is that the officer was always patient and not just

at that time.

This phenomenon also affects imperative uses of adjectives, so,

while we can accept:

Don't be angry

because we understand that being angry or not is a factor which

the hearer can control, we cannot accept:

*Don't be English

because one's nationality is a state not a factor under the

personal control.

The same phenomenon also affects whether a verb may be used

progressively or statively so there is clearly a distinction

between, e.g.:

John was being interesting

and

John is an interesting man

The rule is that stative adjective use can be both predicative and attributive but dynamic adjective use demands only the predicative form.

And this is, of course, a semantic rule which determines a syntactical event.

|

Proleptic use |

The general rule is, as you know, that adverbs modify verb

phrases and adjectives noun phrases so we get:

Work slowly

and

The work was slow / It was slow work

This is, naturally, a purely syntactical rule to do with examining

the structure of the sentence or clause and determining what word

class is

being modified and then selecting the correct word class to fill the

slot in the clause. There is no difficulty filling slots such

as:

Mary was driving __________

and

Mary is a __________ driver.

However, here are some examples in which the rule appears to

break down:

Hammer it flat

Make it wet

Play it loud

Pull it straight

Roll it smooth

Pull it tight

and in all these cases we have a simple imperative clause with a

transitive verb and a pronoun object. The syntactical rule

should allow only an adverb to fill the slot but the sentences are

all well formed.

The solution lies in meaning, as usual. The adjectives here

are not being applied to the verbs (because that is disallowed by

the rules of English syntax) but to the objects of the verbs which,

in this case, are pronouns but could be nouns so we can have:

Hammer the iron flat

Make the paper wet

Play the music loud

Pull the cloth straight

Roll the pastry smooth

Pull the rope tight

Meaning, not syntax, rules.

|

Transitivity |

It is a fairly simple matter to divide verbs in English into those that:

- Intransitive verbs:

which never take an object such as: go, come, arrive, cough, happen and a few hundred more and form clauses such as:

She arrived at the hotel

but not

*She arrived the hotel - Ambivalent verbs:

which may take an object or not such as: break, close, drive, finish, eat, smoke and hundreds more and form clauses such as:

We ate late

and

We ate lunch - Transitive verbs:

which are those that must take an object such as: believe, consider, lose, receive, take and hundreds more and form clauses such as:

I lost my wallet

but not

*I lost - Ditransitive verbs:

which are those that can take both a direct and an indirect object such as: ask, give, hand, tell, offer, pay, promise and a few hundred more (probably) which form clauses such as:

They gave the money

They gave me the money

They gave the money to me

but not

*They gave

and the rules we apply to the verbs are all syntactical to do with where we place the objects (if they are permitted) and what order they come in.

However, a glance at the following examples will show that there are also lexical, semantic rules in action here, too.

- He considered the issue

He considered her a fool - The chair broke

She broke the chair - He read a book

He read them a story - She called at seven

She called her father - She built me a house

She built a house for me

She brought me a shirt

She brought a shirt to me

Here are some notes:

- The first of these examples concerns the meaning of the verb

consider. If it means think about, then

it is monotransitive and conforms to the usual rules.

However, if it means deem or regard, the two

objects become co-referential and the verb takes an object

complement.

The syntax is altered to take account of the meaning. - Here we have a case of the appropriacy of the subject.

If the subject is animate (or at least active) and acts upon the

object, the verb is transitive and must take an

object.

If, on the other hand, the subject is inanimate, the verb is intransitive and cannot take an object while retaining the same meaning.

In the second case, the verb means damage seriously and in the first, it means become unusable.

In the second sense, too, we have what is called an ergative form. The ostensible, semantic object of the verb is, in fact, the chair but the ergative use raises it to the syntactical subject. - With this pair the focus falls on the meaning of read. When it means speak aloud, the verb can be ditransitive or monotransitive but when it takes its usual meaning, the verb is stubbornly monotransitive. The syntax, again, has to be altered to take account of meaning.

- The verb call means either visit (in which case it is intransitive) but when it means telephone it is transitive or intransitive. Moreover, when it is used transitively, it can only mean telephone.

- This is a clear case of a ditransitive use of the verbs but,

unfortunately, the dative shift with build only works

with the preposition for and not with the usual one, to. So

we allow:

She built a house for me

but not

*She built a house to me

The verb bring is more forgiving and allows both formulations.

The reason lies in the meaning, as usual. When the indirect object is the beneficiary, the usual choice falls on for but when the indirect object is the recipient, the choice usually falls on to.

The verb bring can imply either a recipient or a beneficiary and that is why both pronouns are allowable with the dative shift so we can have:

She brought a shirt to me

with the indirect object as the recipient

or

She brought a shirt for me

with the indirect object as the beneficiary

Hence, too, we have, for example:

She sent me the letter

She sent the letter to me

because the indirect object is the recipient but we can also allow:

She cooked me a meal

She cooked a meal for me

because the indirect object is the beneficiary.

That's rather subtle but a question of meaning not syntax.

Other verbs depend heavily on meaning for syntactical accuracy.

For example, speak and talk can be intransitive

(when they mean say aloud or exchange information and

ideas) but say and tell are never

intransitive. The verb tell, when it means inform

is transitive and can be ditransitive but does not allow the dative

shift at all because the meaning does not concern the indirect

object, it concerns the information so:

He told me the train was delayed

is not convertible to

*He told the train was delayed to me

However, when it concerns the act of communicating rather than

informing, the dative shift is allowed

She told a lie to her boss

So, because the sense of the verb has shifted, so the syntax shifts

to follow.

The other notable feature is when the direct object of tell

is a nominalised clause, an indirect object is required because the

meaning of the verb is inform and that verb is, by nature,

transitive.

We allow:

She told me when the meeting started

but not:

*She told when the meeting started

and the syntax is under the control of the lexis.

| All the issues covered above appear in the guides to the relevant areas but here they are brought together. For more, try: | |

| passive voice clauses | for more consideration of the constraints on passive voice structures |

| relative pronoun clauses | for some consideration of both meaning and syntax with these forms |

| place adjuncts | for a little more on PP complement verbs |

| tense and aspect | for lots more on the uses of aspects in English |

| stative vs. dynamic uses | for more on verb types in this regard |

| adjectives | for the in-service guide to the area |

| the article system | for the in-service guide to the area |

| verb types and clause structures | for a good deal more on clause structures and verb meanings |

Reference:

Halliday, MAK, 2014, Halliday's Introduction to Functional

Grammar, 4th Edition, revised by Matthiessen, C, Routledge:

Abingdon, Oxon