Chomsky

Why does one writer get a whole guide to himself?

Quite simply because he is so influential. His ideas penetrate nearly all areas of the study of language. Henk Van Riemsdijk, himself an influential figure and Professor emeritus of Linguistics at Tilburg University, The Netherlands, writes:

I had already decided I wanted to be a

linguist when I discovered this book. But it is unlikely that I

would have stayed in the field without it. It has been the single

most inspiring book on linguistics in my whole career.

In Chomsky

(2002)

Frank Palmer (1971:135) has said of the book that it was

the book that first introduced to the world the most influential of all modern linguistic theories, 'transformational-generative grammar'.

The book in question was: Syntactic Structures, first published in 1957.

Word of warning: what follows is an overview of the classic

version of Chomsky's theories concerning Transformational-Generative

Grammar (TGG). As such, it can only do some injury, minor, it

is hoped, to the complexities and subtleties of the approach.

For more, consult the literature. There are some references

at the end but there is a wealth of literature in the field.

In addition, there is Chomsky's own website at

www.chomsky.info

and many more or less reliable websites covering the area. The

briefest of overviews concerning some theories of Chomsky in cartoon format can be viewed at

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=7Cgpfw4z8cw.

|

Part 1: Transformational-Generative Grammar (TGG) |

Background: Structural Linguistics

Attached to the name of Bloomfield and his followers,

Structural Linguistics is/was the attempt to apply a truly scientific

approach to grammar. Although all linguists are concerned to

study structure, or patterns and regularities, in language, of

course, Bloomfield's central concern was with a mechanistic and

purely empirical approach to language study, looking for structure,

not meaning.

Structural linguistics defined the essential building blocks of

language as phonemes and morphemes, the latter consisting of

combinations of the former, and the approach to analysing grammar

was to divide the language up into its 'Immediate Constituents'.

Hence, we have IC analysis: Immediate Constituent analysis.

The details of IC analysis need not concern us here but the result

was to analyse language according to a branching tree diagram.

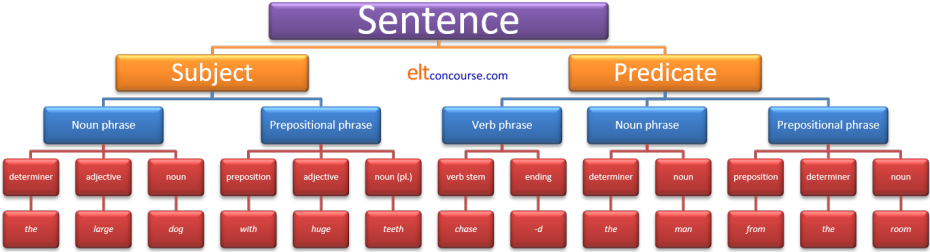

IC analysis can be quite illuminating. Here's an example of

what is meant. If we analyse the sentence

The large dog with huge teeth chased

the man from the room

into its immediate constituents we

can do so like this:

(Here, we have not inserted a row of phonemic analysis below the

level of morphemic analysis but it is possible to do so and break

down each morpheme into its constituent phonemes so we would have,

e.g.:

the = /ð/ = /ə/

large = /l/ + /ɑː/ + /dʒ/

dog = /d/ + /ɒ/ + /ɡ/

etc. and so on for each morpheme.)

This kind of analysis can be fruitful because it is simple to

see that we can substitute the sequences of morphemes in the bottom

row with others and, while maintaining the same analysis, apply it to

any number of sentences. We can analyse, e.g., a sentence such as

The old man with grey hair dropped his keys

in the street

which follows the same pattern:

| Determiner | Adjective | Noun | Preposition | Adjective | Noun | Stem | Ending | Determiner | Noun | Preposition | Determiner | Noun |

| the | old | man | with | grey | hair | drop | -(p)ed | his | keys | in | the | street |

While such an analysis works well for many examples of well-formed sentences, there are some problems.

|

Problem 1: embedding |

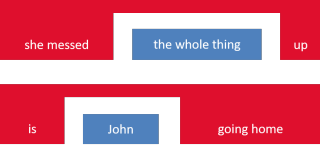

This all works very well when sentences behave themselves and come along quietly with all the constituents in order. However, the first problem strikes when we consider sentences such as:

- She messed the whole thing up.

- Is John going home?

The problem is that while it's easy to see that the verb phrase in

sentence 1. is

mess + -ed + up

and in sentence 2. it is

primary auxiliary + stem + -ing

no simple tree diagram will

allow this separation of verbs by objects (sentence 1.) or verbs by

subjects (sentence 2.).

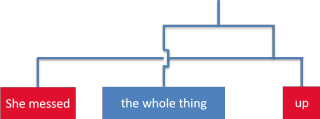

It has been suggested that one could represent these sorts of embedded ideas this way:

or we could have crossing lines like this:

but that defeats the purpose because IC analysis depends on the possibility of substituting sequences with other sequences and discontinuous phenomena like these are not sequences at all.

|

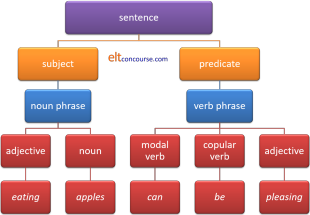

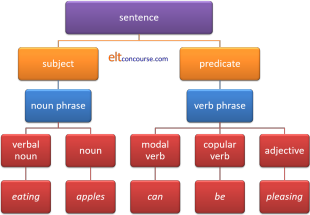

Problem 2: ambiguity |

The issue here is to know how to divide the

constituents up and what class of word or phrase to assign to each.

Try

analysing:

Eating

apples can be pleasing

this way and you'll see what is meant.

What's the difference between the following?

|

|

Click here when you have seen the difference.

The only difference is in how we describe the first word. If it's an adjective then it refers to the fact that the sorts of apples we call eating apples can be pleasing but if it's a noun (i.e., a gerund), then we are referring to the act of eating apples which can be pleasing. If we remove the modal, it becomes clear:

- Eating apples are pleasing.

- Eating apples is pleasing.

A more famous example of this problem

for structural

linguistics is:

Visiting aunts can be boring.

Is it the action of

visiting aunts or the aunts themselves which/who can be boring?

There is a guide to ambiguity on this site, linked at the end, which

considers this sentence in particular (and accuses Chomsky of

cheating a bit).

|

Transformational-generative grammar to the rescue |

Clearly, Chomsky's ideas have two parts so we'll take them individually.

|

Transformational |

Instead of relying on tree diagrams to represent how sentences

were constructed from individual morphemes, Chomsky was concerned to

discover the patterns by which one sentence could be transformed

into another. The classic example is the passive in English.

How is

Mary allowed Peter to go home

transformed into

Peter was allowed to go home, by Mary?

Here's how

(Chomsky, 2002:43):

If S1 is a grammatical sentence of the

form

NP1

— Aux — V— NP2,

then the corresponding string of the form

NP2

— Aux + be + en — V — by + NP1

is also a grammatical sentence.

To explain:

S1 is the first or kernel sentence.

NP1 and

NP2 are the noun phrases (Mary

and Peter in our examples).

V is the verb (allow in our examples)

Aux stands for the tense marker,

not necessarily an auxiliary verb, (the past of allow and

be in our examples)

en is the marker for past participle.

So the rule for transforming the active, kernel

sentence into the passive is:

- put NP2 first

so we get:

Peter ... to go home - add the

tense of the verb be

so we get:

Peter was ... to go home - add the past participle of the main

verb

so we get:

Peter was allowed ... to go home - add by

so we get:

Peter was allowed by .... to go home - insert NP1

so we get:

Peter was allowed to go home by Mary

Easy, and the last two steps are optional, of course, because by step 3. we have a well-formed passive-voice clause.

|

So what? |

So quite a lot.

Instead of the cumbersome tree diagrams for every sentence, we now

have a set of rules to work from to transform kernel sentences

(i.e., the original from which we make the transformations) into

others and we have a way of dealing with both the embedding problem

and the ambiguity problem we met above.

|

Embedding |

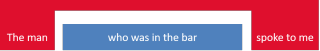

For example, if we take a sentence such as

The man who was in the

bar spoke to me.

the structural linguistics analysis

would either have lines crossing each other or result in the kind of

block diagram we saw above, like this:

However, we can look for the kernel sentences which make it up and then work out the transformation rules. Like this:

- The kernel sentences are:

- The man spoke to me.

- The man was in the bar.

- The transformation rules are:

- Place the second sentence after the first NP in the

first sentence.

That gives us:

The man the man was in the bar spoke to me - Replace the second NP with who.

That then gives us:

The man The man who was in the bar spoke to me

- Place the second sentence after the first NP in the

first sentence.

We can do the same thing with other forms of relative pronoun sentences, transforming, for example:

- I cut down the tree

- The tree was hanging over the gate

by using similar rules to generate:

- I cut down the tree the tree was hanging over the gate

which involves placing the second sentence after the noun phrase in the first sentence - I cut down the tree the tree

which / that was hanging over the

gate

which involves replacing the second noun phrase with which or that

Other relative pronoun sentences can be generated slightly differently so from:

- I cut down the tree

- The tree was hanging over the gate

we apply other rules:

- Move the first sentence to the front of the second and

produce:

I cut down the tree the tree was hanging over the gate - Delete the first noun phrase to produce:

I cut down the tree the tree was hanging over the gate - Delete the second verb phrase and produce

I cut down the tree was hanging over the gate

This is called the relative transformation, by the way.

|

Disambiguating |

The often-cited example of an ambiguous statement which

transformational-generative grammar can deal with is:

The

shooting of the hunters was terrible.

The ambiguity, of course, is that we don't know whether the

hunters were bad shots or whether they were shot.

Here's how TGG can unravel the problem:

- The key noun phrase is the shooting of the hunters

- This noun phrase can come from two possible kernel

sentences:

- The hunters shot (something)

- The hunters were shot

- Once we know which of the kernel sentences produced the noun phrase we have disambiguated the sentences.

This is an example of the workings of deep structure. I.e., the structure of the sentence which derives from the nature of the kernel sentences and is below the surface structure traditionally analysed in structural linguistics. There are two possible deep structures here identifiable from the two possible kernel sentences.

As another example, we can take our earlier

sentence

Eating apples can be pleasing.

Can you apply

the transformational approach to disambiguating the two meanings?

Click here when you have.

- There are two possible kernel sentences:

- Something can be pleasant

- (Someone) eats apples

- If the sentence derives from (can be transformed from) a., the meaning is that we are referring to apples grown to be eaten rather than cooked.

- If the sentence can be transformed from b. then the meaning refers to the act of eating apples.

|

Generative |

The idea of a grammar being generative is the second string of the theory.

Simply put, this means that the grammar must be capable of generating 'all and only' the grammatical sentences of the language. This does not mean that it must do so, only that it must be capable of doing so. For example, a generative grammar must be able to produce She likes apples but not Like apples she and so on.

There is a fundamental difference of approach here from that taken by structural linguists.

- Structural linguists were concerned to identify the sentences of the language and then analyse them. In other words, they collected a corpus of data and then analysed the data working from the phonemes making up each morpheme upwards to make the tree diagram we are familiar with.

- A generative approach is not concerned with what has been

observed but with what is possible. A corpus of data (even

a huge, modern computer-based one),

however large, cannot contain all the sentences of a language

and will inevitably miss some out. This is because any

language contains an infinite number of

possible sentences.

For example, I can say,

The man who was in the room was reading.

I can then add another relative clause to make

The man who was in the room which was on the second floor was reading

and I can continue to add clauses to make, e.g.,

The man who was in the room which was on the second floor which was part of the building which was in the High street was reading

and so on ad infinitum. There is theoretically, no limit although the sentence will, of course, become unmanageable and harder and harder to understand as it grows. That's not the point; the point is that it is theoretically possible never to come to the end of the sentence.

In Syntactic Structures, Chomsky demonstrates the generative nature of this sort of grammar by considering the form of the negative in English. This is not the place to repeat all the steps but the conclusion is (op cit:62):

The rules (37) and (40) now enable us to derive all and only the grammatical forms of sentence negation

As you may imagine, rules 37 and 40 are somewhat complex but that they can be used to produce all and only the grammatical forms is not in dispute.

|

Competence and performance |

The key here is that TGG is not concerned with analysing that which is actually said but with establishing the rules concerning what can be said. For many, involved as they are in analysing what people actually say and write, this is a central weakness of Chomsky's position.

- What is actually said by speakers of the language is called performance and is not the concern.

- What is possible for a speaker to say is called competence and is the concern.

According to the theory, then, what happens is that speakers of a language work to an internalized set of rules from which they generate grammatically accurate language. The proper concern of grammar studies, then, is to find out what these rules are and that cannot be done solely by looking at what is said but by considering what can be said.

There are, however, obvious problems with this simple distinction:

- Who judges what is and is not grammatical? Is, e.g.

This car should have been being serviced

grammatically correct? At a formal level, none of the 'rules' of the language has been transgressed but many would reject such a sentence.

Chomsky's response to this charge was to rely on what he termed intuition and that is a native speaker's judgement of correctness and appropriacy. - How complex do we allow sentences to be? Is, e.g., our

example above

The man who was in the room which was on the second floor which was part of the building which was in the High street was reading

acceptable? If it is, how about something like

The old, tall, talkative and somewhat eccentric man who was in the long, thin, well-lit, poorly decorated room which was on the second floor which was part of the newly-built but apparently only half-finished building which was in the bustling and crowded High Street which was in the centre of the small but attractive and rapidly growing town which was in the County of Kent which is in the South-East corner England was reading a book which he had recently bought from a shop on the corner?

Native speakers know that they need to draw a line somewhere but it is extremely difficult to generate a rule to say where that line lies.

|

Re-write rules |

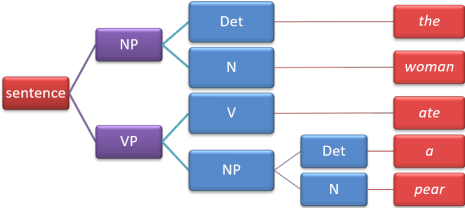

Re-write rules look similar to the structuralist tree diagrams we have seen above but they are different insofar as they are intended to generate grammatical sentences rather than simply analyse them. Here's an example to generate (not simply analyse) the sentence:

The woman ate a pear.

Breaking this down, we can get:

| 1 | S | → | NP + VP | i.e., the Sentence should be re-written as Noun Phrase + Verb Phrase |

| 2 | VP | → | V + NP | i.e., a Verb Phrase consists of a Verb + a Noun Phrase |

| 3 | NP | → | Det + N | i.e., a Noun Phrase consists of a Determiner + a Noun |

| 4 | V | → | ate | i.e. the verb in this case is the past form of eat |

| 5 | Det | → | the, a | i.e., there are two distinct determiners (both articles) |

| 6 | N | → | woman, pear | i.e., there are two nouns |

We can, of course, represent this sort of phrase structure

analysis in the same kind of branching tree diagram we saw above.

So we get:

What is exemplified here, by the way, are PS-rules (phrase structure rules).

There are two things to note:

- Rules like these will generate a number of different

sentences, e.g.,

The woman ate the pear

A woman ate the pear

A woman ate a pear.

The rules will also generate unacceptable sentences, however, such as

The pear ate the woman

A pear ate a woman

The pear ate a woman.

It will also generate the truly ungrammatical:

A man stood the forest

A person arrived a hotel - We can combine re-write rules with transformational rules

and that, as we saw above, can transform

The woman ate a pear

into

A pear was eaten by the woman

by the removal of the second noun phrase to the front of the sentence and making changes to the verb as above.

In other words:active passive NP1 — Aux — V — NP2 → NP2 — Aux + be + en—V— by + NP1 The woman tense of verb (ate) the pear transforms into The pear tense of be (was) participle form (eaten) by the woman

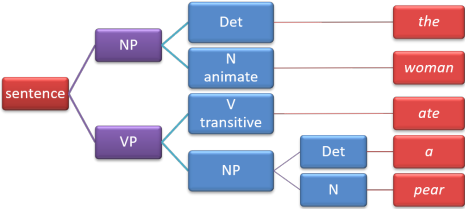

However, getting around the problem of generating statements such

as

A pear ate a woman

A person arrived a hotel

is not an easy matter.

This is done by stating upfront what kind of main verb is permitted

with what kind of noun. We forbid a certain class of noun

(i.e., here, ones as subjects which are not animate) and certain

classes of verb (i.e., ones which are not transitive). Then

the restrictions only have to be stated once in either our

phrase-structure or transformation rules which we apply.

So we get:

Now this form of phrase-structure analysis cannot generate

The pear ate the woman

or

A person arrived a hotel.

because The pear is not animate and arrive is not

transitive.

What's more, applying these restrictions to the kernel sentence

means that our transformational rules cannot produce

The woman

was eaten by the pear

but will generate

The pear was eaten

by the woman.

The rules will also produce odd-sounding sentences such as

The bear ate the house

although we could get around that by

specifying the kind of noun which slots into the

NP2 position

but, recall, we are concerned with

possible sentences, not language that is

actually produced.

Such an approach, combining the phrase-structure

rules with transformational rules, can generate, for example,

- The dog broke the window.

- The window was broken by the horse.

- A picture was stolen by a thief.

- The man injected the dog.

- The vet cured the dog.

- Some men broke the door.

- Those people enjoyed the fruits.

and so on and so on. Each and every sentence produced in this way will be grammatical. That is the power of phrase-structure rule generation.

|

Part 2: The Language Acquisition Device (LAD) |

We have seen above that the rules governing the generation of

grammatically correct sentences are subtle and at times very

complex. The question naturally follows:

How do we learn the rules?

A behaviourist view of learning would state that we simply hear

and repeat correct utterances in our first language and attend to

the feedback (positive or negative) that we get from, e.g., parents

and other adults.

We adjust what we say according to the type of feedback we get like

this:

- Reject language behaviour which is negatively or not reinforced.

- Commit language which seems to be approved to our longer-term memory.

|

Examples of the problem |

As an example, we'll use question formation in

English and start with a declarative sentence:

A unicorn is in the garden

and make the question:

Is a unicorn in the garden?

and that was simple enough because the rule is to take the

primary auxiliary verb and move it to the beginning. That

means we can generate any number of correct interrogative forms by

applying the simple rule so, for example:

A man is outside → Is a man outside?

You can see it → Can you see it?

John was in the garden → Was John in the garden?

and so on for, quite literally, millions of sentences.

However, now make a question from:

A unicorn which has a golden horn is in the garden

Click here when you have done that.

The

question now is that if we apply the rule we induced from the first

example (i.e., move the auxiliary verb to the beginning), we get:

Has a unicorn which a golden horn is in the garden?

and that's nonsense.

The rule now is: move the second auxiliary verb to the beginning but

leave the first one alone. Then we get the acceptable (if

slightly unusual):

Is a unicorn which has a golden horn in the garden?

That is a complex and non-intuitive rule. However, it has been demonstrated that all children by around the age of

four can do this unfailingly and never produce the nonsense.

Here's a second example of the issue, one often cited as counter

evidence to a behaviourist view of language acquisition.

When we decide whether or not to put an -s ending on the

base form of the verb requires us, in English, to make 4 decisions:

- whether the verb is in the 3rd person

- whether the subject is singular or plural

- whether the action is present tense

- whether the action is in a simple, progressive or perfect aspect

Then, having considered those four points, to learn the system children must:

- Notice that some verbs come with an s- ending in some sentences but not in others

- Search for the grammatical causes of this phenomenon (rather than accepting it as random variety)

- Sift out all the irrelevancies and identify the causal factors (1 to 4 above)

By around three years of age, children get this right at least

90% of the time.

Not only that but en route they use it inappropriately (bes,

gots etc.) which they can't have heard so are not

imitating because those malformed examples cannot have been heard.

The fundamental problems Chomsky (and others) see with how children manage to produce such complex grammar so early are:

- There aren't enough data:

Children acquire language very quickly and are making complex, grammatically correct sentences at a very early age. By this stage in their development, they simply haven't been exposed to adequate information about the language to be able to do so.

This is a debatable point because, in fact, normally brought up children are exposed to enormous amounts of data, certainly enough to base a linguistic corpus on before they are five years old. - The data are not always grammatical:

Studies show that carer-speak is focused on meaning not structure and that very young children in particular are exposed to a lot of language which is ungrammatical. If that is the sole source of their production, much of it would remain at the 'Get choo-choo' level of speech.

This, too, has been challenged and, for example, one study found that of 1500 utterances analysed, only one was ungrammatical (or a disfluency, in the jargon). The study found that the speech of carers directed towards children was 'unswervingly well formed'

(Newport, Gleitman and Gleitman, 1977:121, cited in Moerk 2000:96) - Reinforcement is unreliable and inconsistent:

- adults do not consistently respond positively to grammatically correct utterances. They respond to meaning (and sometimes cuteness) more often than not, however malformed the child's language output is.

- adults do not always provide loud and enthusiastic reinforcement (as the behaviourist theory would require). They often speak quietly, or even not at all, in response to whatever the child produces.

Chomsky states it this way:

Language is not a habit structure. Ordinary linguistic behaviour characteristically involves

innovation, formation of new sentences and patterns in accordance

with rules of great abstractness and intricacy.

(Chomsky (2003) p 349)

There's an allied problem that, although many animals communicate

with each other (sometimes sending quite sophisticated signals),

only humans have developed such a complex and subtle system of

communication: language. (And if you have trouble with that

idea, try the guide to theories of language evolution, linked

below.)

The conclusion is that something else is going on.

What is going on according to Chomsky is that the child is using a genetically inherited Language Acquisition Device which is hard-wired in the structure of our brains. We are, therefore, inherently prepared to analyse the structure of whatever first language(s) we are exposed to as infants.

What this means is that, before we even leave the womb, our

brains are prepared for the kinds of phrase structures and

transformational rules we will need to process the language we hear.

Some have compared this to a kind of internal switchboard with which

we can categorise input making guesses and assumptions such as

"Aha! This language uses a Subject - Object - Verb ordering but

seems to place adjectives after nouns"

and so on.

How this works lies in the field of first-language acquisition

theories, to which there is a guide on this

site (linked below).

An allied concept is known as the Critical Period Hypothesis which is the source of a good deal of debate concerning its existence and, if it exists, its definition. The two key issues are:

- The definition.

Many theorists will claim that it starts around the age of three and stops at around the age of 13 (or so) by which time it becomes much more difficult for people to acquire native-like use and pronunciation of the target language. - Whether and what extent the LAD is available to adults.

The assumption is often that children acquire a second or subsequent language quite easily because, some say, they retain access to the LAD. After a certain age, it is argued, people have to rely on less efficient generalised learning mechanisms. An intermediate position is taken by those who contest that some elements of the system remain available but some are forever lost to adults, particularly the ability to attain native-like pronunciation.

|

The evolution of the ability to process language |

There is, unsurprisingly, some debate among evolutionary biologists concerning how such a mechanism may have evolved. Recent genetical research is pointing to a set of genes including one called FOXP2 which looks like this:

It would be a gross oversimplification to dub this 'the language gene' as much else, including the interactions between this gene and a range of others and with the environment, is involved in the ability to process language. FOXP2 is what is known as a transcription gene. It does not have a direct effect but it acts to switch on, or off, other genes. What these other genes are exactly and what they do is still not fully understood. However, the gene appears to be central to our ability to process and produce language and people who lack it or in whom it is mutated or inactive cannot handle language. Incidentally, this gene has been identified in the DNA extracted from Neanderthal bones (and it also occurs in echolocating bats and songbirds).

There is a good deal more about theories concerning the evolution of language in the guide, linked below.

Summary

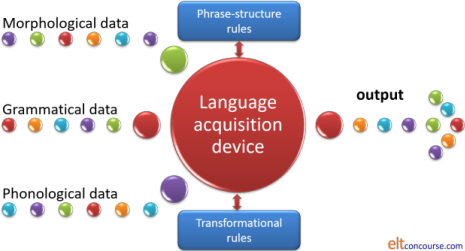

The LAD can be visualised as operating in combination with phrase-structure and transformational rules something like this:

|

Part 3: Universal Grammar (UG) |

An allied theory is that there is, therefore, something called

Universal Grammar. This is supposed to be a set of categories

and rules common to all languages, no matter what their individual

grammatical structures are like and no matter what sorts of

languages they are (isolating, agglutinative, synthetic and so on).

The basis for this reasoning is that without such a UG, children

would have nothing on which to use the LAD.

Pinker sums up the viewpoint of those who accept the idea of a Universal Grammar like this:

According to Chomsky, a visiting

Martian scientist would surely conclude that aside from their

mutually unintelligible vocabularies, Earthlings speak a single

language

Pinker, 2007: 232

This has obvious implications for teaching:

- If a UG exists then our learners already have the concepts of things such as noun phrases, adjectives, verb phrases and so on and can use these universal concepts to understand the structure of a language they are learning.

- It is not, in other words, new to them that we can use the kinds of tree diagram, phrase-structure analysis we saw above.

- It will also not be new to them that we can, by employing comprehensible rules, transform a set of kernel sentences into a new structure.

Not to take advantage of learners' inherent knowledge would seem, therefore, to be somewhat perverse, wouldn't it?

|

The sceptics |

There are many, however, who are deeply sceptical of the sustainability of many of Chomsky's theories (with the possible exception of a general acceptance that humans are, indeed, genetically disposed to learn languages).

|

Scepticism #1 |

Studies in comparative linguistics reveal that the existence of language universals is questionable. Evans and Levinson put it this way:

Languages are

much more diverse in structure than cognitive scientists generally

appreciate. A widespread assumption among cognitive scientists,

growing out of the generative tradition in linguistics, is that all

languages are English-like, but with different sound systems and

vocabularies. The true picture is very different: languages differ

so fundamentally from one another at every level of description

(sound, grammar, lexicon, meaning) that it is very hard to find any

single structural property they share. The claims of Universal

Grammar, we will argue, are either empirically false, unfalsifiable,

or misleading in that they refer to tendencies rather than strict

universals.

Evans & Levinson, 2009:2

Evans and Levinson, and others, go on to point out that the supposed 'big four', nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, are not, in fact universals of human language at all. There are languages which cope happily without adverbs and some without adjectives (Lao, for example). The jury is still out (and has been for over 100 years) considering whether there exist languages without verbs or nouns but there are certainly languages which combine verbs with nouns so that something like the verb cut will vary depending on what is being cut so the expression for cutting wood, for example, will be a different verb from cutting meat and so on.

On the other hand, there are word-class categories in some languages

which do not have equivalents in others. Examples are the

classifiers which exist in many East Asian languages, ideophones

(single words to describe entire events or states) and obscure (to

speakers of Indo-European languages) categories such as positionals

(which refer to how objects are arranged in space)

and coverbs (which function a little like delexicalised verbs in

English but are syntactically unique).

They sum up, op cit.: 14 like this:

the great variability in how languages organize their word-classes dilutes the plausibility of the innatist UG position

|

Scepticism #2 |

The other connected criticism directed at Chomsky is his dependence on the analysis of just one language: English. He defends the position, unapologetically like this:

I have not hesitated to propose a general

principle of linguistic structure on the basis of observation of a

single language. The inference is legitimate, on the assumption that

humans are not specifically adapted to learn one rather than another

human language ... Assuming that the genetically determined language

faculty is a common human possession, we may conclude that a

principle of language is universal if we are led to postulate it as

a ‘precondition’ for the

acquisition of a single language.

(1980, p. 48)

The counter argument to this is that, in fact, languages differ

very fundamentally from English in an almost infinite number of

ways. Many, for example, will not even have a recognisable

passive structure or recognisable embedded relative clauses.

In some languages, for example, verbs contain adjectives and in

others, adjectives themselves are marked for tense like verbs.

Rare and, to many, exotic languages exhibit a bewildering and

unfamiliar set of structural and lexical systems which cannot be

interpreted using Chomskyan grammar. generative or otherwise.

Some, e.g., Tofa (a Siberian language) has a suffix (-sig)

which may be appended to any noun and carries the meaning of

smells like. Others may have a range of affixes which

denote particular sounds and so on. Even superficially simple

concepts such as wh-words may vary across languages which

require the speaker to think about the type of noun in consideration

before selecting the correct form of How many ...? to use.

Even superficially simple verbs such as go and give

may be rendered in ways which require the speaker to consider the

direction and type of travelling which is being undertaken or the

nature of the object of the verb give. Such

subtleties are not, it seems, accessible through transformational

generative grammar of the sort that Chomsky outlined.

The issue here is that many cognitivists are not particularly

interested in or well informed about the possible structures of

languages with which they are unfamiliar and the counter argument is

that language typologists are too interested in the minutiae of rare

language structures to see the bigger picture. The truth may

lie somewhere in between.

|

Scepticism #3 |

Chomsky was concerned, in his words, to learn something about human nature via the task of studying the properties of natural languages. (Chomsky, 1974:4)

Unfortunately, many argue, this has been interpreted so narrowly

so that the content of what people say has been lost from the task

of studying the properties of natural languages. Chomsky

himself (ibid. emphasis added) refers to the

structure, organisation,

and use of

languages but the last part has been neglected. He also,

incidentally, refers to languages in the plural which goes some way

to countering the objections above.

The argument goes on that we cannot understand people's languages if

they are divorced from their cultural and social contexts and

studied in a vacuum.

With reference to language teaching and English Language Teaching in

particular, Hymes stated (1971:278):

There are rules of use without which the rules of grammar would be useless.

For example, a rule of use in English-speaking cultures is that

direct statements of wishes are generally perceived as rude so they

are normally tempered or rephrased to provide some distance.

It is perfectly possible in English and probably in all languages to

say:

I want that

or

Give me a coffee

but, in English and a range of languages, there is a rule of use

which disallows such directness and requires something like:

I would like that

or

Please give me a coffee.

Honorifics, too, are subject to rules of use just as strict as

rules of grammar. English has a fairly simple system requiring

honorific use in some settings (courtrooms, schools, formal meetings

and so on) but Japanese, to take a well-known example, appends

honorifics to nouns and verbs in a complex manner which is not,

arguably, something that structural linguistics of any sort can deal

with adequately.

So, before we get too enthusiastic about using Chomskyan theories to inform our teaching we should remember that he was addressing the ways in which:

- the language is structured at an abstract level (i.e., at the level of competence not performance).

- our first (not subsequent) languages are acquired.

Chomsky is not fundamentally concerned with second language teaching and learning. That his theories may inform those who are, is another matter.

| Related guides | |

| Krashen and the Natural Approach | for the guide to this set of hypotheses |

| how learning happens | for a general and simple overview |

| first-language acquisition | for a guide to some current theories and how they may be relevant to teaching languages |

| second-language acquisition | for a guide to some current theories |

| language evolution | for the guide reviewing some major theories in the field |

| language, thought and culture | for an overview of theories linking language and thought and whether one determines the other or vice versa |

| input | for a related guide concerning what we do with the language we hear and read |

| ambiguity | for the general guide to other forms of ambiguity in English |

| types of languages | for a guide relevant to Universal Grammar |

| communicative language teaching | for more on a non-structural view of teaching and learning |

References:

Chomsky, N, 2002, Syntactic Structures (2nd Edition), New

York: Mouton de Gruyter

Chomsky, N, 1980, On cognitive structures and their development:

A reply to Piaget, in: Language and learning: The debate

between Jean Piaget and Noam Chomsky, pp. 35–52, Harvard, Mass.:

Harvard University Press

Chomsky, N, 1975, Reflections on Language, New York:

Pamtheon

Chomsky, N and Otero, CP, 2003, Chomsky on Democracy & Education,

Psychology Press

Evans, N & Levinson, S, 2009, The Myth of Language Universals:

Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science, in

Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Hymes, D, 1971, On communicative competence, in Pride, J & Holmes

J (Eds.), Sociolinguistics, London: Penguin

Lyons, J, 1970, Chomsky, New York: Viking Press

Moerk, EL, 2000, The Guided Acquisition of First Language Skills,

Stamford: Greenwood Publishing Group

Palmer, F, 1971, Grammar, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Pinker, S, 2007, The Language Instinct, New York, NY:

Harper Perennial Modern Classics

(For more on FOXP2 and its role in language development, try the

eminently accessible ScienceDirect article at

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929707629024)