How learning happens: the essential guide

This is not a website about psychology but there are some fundamental

ways of seeing learning that you should know about.

What follows refers to second-language learning, not

how we acquire our first language(s). For that, you should refer

to the guide to

Chomsky and the guide to the

differences and

similarities between first- and second-language learning. Both

guides are linked in the table of related guides at the end.

|

Deductive vs. Inductive learning |

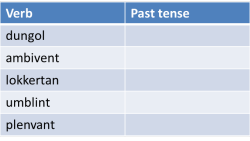

Look at this:

In this language the past tense is formed by adding em- to

the front of the verb if it begins with a vowel or just e- if it

begins with a consonant.

What is the past tense of the following

verbs?

Click on the table when you have an answer.

Easy? Yes, but it was meant to be. The rule was very

simple and most real languages are not at all so accommodating.

What you have

demonstrated is your ability to learn deductively.

You were given the rule and from it could deduce the correct form of the

verbs.

Now try this one.

In this language the plural of some common

nouns is as follows.

What are the plurals of the three nouns at

the end of the list?

What is the rule for forming plurals?

Click on the table when you have an answer.

Not quite so easy because you had three forms to consider. However, if you successfully completed the task, you have demonstrated your ability to learn inductively. You were given the examples and from there you worked out the rule and applied it to the three unknown items.

This distinction in how things are learnt underlies many teaching procedures and the way items of language are presented in coursebooks and other materials.

For example, we can give people a set of rules about how to lay out a

formal letter (sender's address at the top right, recipient's address on

the left, date below the sender's address and so on). Then we can

ask the learners to construct a letter with correct layout. That's

a purely deductive learning approach.

On the other hand, we can give the learners two or three examples of

formal letters laid out conventionally and ask them to look at the

layout. Then we can ask them to work out what the rules are and

apply them. That's an inductive approach.

There are arguments on both sides but the consensus view is often

that inductive approaches are more effective in terms of retention

(because of the effort which is needed) but that deductive approaches

are time efficient in classrooms and good for revision.

It's up to you, of course, which approach you take but you need to

know which it is and why you are

applying it.

|

Which way? |

Much nonsense is spoken about taking either an inductive or a deductive approach to learning. there are three problems with this:

- This is not an either-or distinction. Even if one starts with a purely inductive approach in the classroom, the aim has to be for the learners to hypothesise a rule (preferably the right one) and then apply it to further examples of the target language. The second procedure is, of course, purely deductive. There is little point in putting learners to the trouble of constructing a rule from exemplification if they are not then encouraged to apply it.

- On the other hand, starting with a deductive approach and supplying a rule from the outset nearly always results in the need to refine the rule later to take account of more complex forms. Even if we knew what they are, it would not be possible to supply all the rules for using, say, verb tenses in English so any rule which is presented to learners has to be no more than an approximation.

- Some elements of structure in any language are very complicated and trying to work out what the rules are for, for example, using adjectives in English or getting the case structures right in Finnish from examples only would simply take far too long (and probably fail).

|

Co-text, context and meaning |

How many of the words in the spoof languages above are you able to

remember? Right, one or two at best.

That's because the words were presented to you without any meaning or

context attached to them. It is very difficult to remember

language which has no meaning and is not set in context. If,

however, we put a word in a sentence with some co-text, it's easier for

you to take a stab at the meaning and remember it. For example,

If you don't dungol the dwintii, the water will just keep flowing out.

In this case, we know that dungol is

a verb and that dwintii is a plural

noun (because we remembered the rule better than we remembered the

example, incidentally). It's possible that we won't be wrong if we

imagine dungol means turn off

and a dwint is a tap.

That's much better already. We have added co-text (i.e., other

words around the targets which we do understand).

Language without co-text is not meaningful and very hard to learn.

Now let's add context (i.e., the setting

in which the language occurs):

Now we have context and co-text

so it's much easier to figure out what the language means and how it's

used. How much can you understand now?

Click here when you have a list in your head or on paper.

- we know that umblint is a

verb:

- that can be done by people

- that can be done to objects (it's transitive)

- that might mean something like fetch or get (the younger speaker uses bring in the next sentence so we know it's not that verb)

- whose imperative form doesn't appear to change from the base form

- we know that kluma is a

noun:

- which is singular (referred to as it)

- which means something like watering can because nothing else is on the floor next to the spade

- which can be filled with water (unlike anything else in the picture)

- we know that a genge is:

- a noun which can be the object of bring (so it's probably concrete rather than abstract)

- probably the second object from the left because it looks like something to cut an edge of a lawn with (we may not even know the word for this tool in our first language – do you?)

- singular (there's only one in the picture and the speaker refers to a genge)

- we know that lokkertan is a

verb:

- which you can do to a watering can

- which probably mean something like fill because our knowledge of the world tells us about the relationship between watering cans and water

- whose imperative form is lokkertan (the same as we did for umblint, above)

With a bit of luck, we can also guess that:

Please umblint a glass and lokkertan it with beer = Please fetch a glass and fill it with beer.

We have acquired quite a lot of language from a simple scene and

a four-part dialogue and that's all due to our being given context

and co-text and applying a bit of our knowledge of the world.

Note, too, that we haven't only acquired the meaning of lexis, but

have also gained some insight into word grammar (imperative forms

and plurals etc.).

It is perfectly possible that you will remember the four unknown

words even weeks after you have read this page and that is, of

course, very significant.

Incidentally, you have also probably figured out from your knowledge of the world that the older person is in charge and that phrases such as will you? and please are used to soften the imperative nature of an utterance. Not bad at all.

|

Personalisation |

Right, everyone. Please write down:

- Two things you have at home that you can lokkertan with water

- One thing you can lokkertan with petrol

- When you last used a kluma and what for

- Three things you must umblint today

- If you have ever used a genge

Now, stand up and come to the middle of the room, please. You need to talk to everyone until you find someone who has a list which is completely different from yours by asking questions. Ready? You have 6 minutes. Go.

What's the purpose of this activity? Think for a minute and click here.

- It revises the language and allows people to deploy it in a free(r) stage of the lesson. That helps memorisation.

- It makes the language more memorable because people have to think about themselves and things they have and have done using the target language.

- It allows both you and the learners to check that they have acquired the targets of the lesson.

Personalising the language targets is considered very helpful so it's worth thinking of ways to do it in every lesson you teach.

|

Factors which affect learning |

Before we start this section, think for a moment about what factors inherent to your learners will affect how well they can learn.

Here's a list of factors with some space for comments. Look

through the categories on the left, make up your own mind whether it is

important and why and then click on the

![]() to reveal some comments.

to reveal some comments.

| Intelligence |

There

is some evidence of a correlation between intelligence

(i.e., as measured by IQ tests) and language learning

ability. The evidence is, however, mixed and

theories of multiple intelligence (including linguistic

intelligence) are also relevant here. For more on

that, see

the guide to learning styles on this site, linked below.

|

| Aptitude |

There

is quite a lot of evidence to show that some people are

simply better at learning languages than others.

Tests of aptitude are based on testing the ability to:

distinguish between and memorise sounds,

understand word class and the functions of words

in sentences,

inductively work out grammar and other rules and

memorise vocabulary.

Of course, some individuals may be better at some of these things than others. For example, people may be blessed with a good memory for words but unable to hear intonation patterns and distinguish between sounds easily. |

| Personality |

It is difficult to measure the effect personality

factors may have on learning success. However,

there is some evidence that strongly adventurous and

extrovert people are better at second-language learning and

some to suggest that empathy, self-esteem and lack of

inhibition are also factors. The jury is still

out.

|

| Motivation |

Positive attitudes and high motivation have been shown

to be factors aiding second-language learning. The

problem is to decide whether high motivation leads to

language learning or good language learning feeds back

into high motivation. We enjoy doing what we are

good at.

There is little doubt, however, that classroom techniques which intrigue and involve learners and keep them committed to tasks are beneficial. |

| Beliefs about learning |

There

is some evidence to show that when the learners' beliefs

about how a language is best learned are in conflict with

how the instruction is provided that learning is less

successful. This may be connected to the

motivational factors.

|

| Age |

There

is some evidence of a correlation between age and

second-language learning success, especially with regard to

pronunciation and speaking skills generally. The

younger you start, the more native-like will be your

production.

There is also a good deal of evidence to show that pre-puberty learning is more effective than learning as one ages. Some studies have shown that there is a critical period for second-language learning and that it lies between the ages of 3 and 15. |

A further important factor concerns the relationship between the

learner's first language (or one of them) and the target language.

The more closely related these are, the easier it will be learn the

second or subsequent language.

There are, of course, classroom factors over which you have some

control such as the atmosphere in the room, your approach and the nature of the

environment. Given that many of the factors which affect

learning are not amenable to change by teachers, we should take

advantage of the ones that are.

For more, see the guide to motivation, linked below.

|

Noticing |

Noticing is being consciously aware of the language you see and

hear (noticing language) and the gap between what you produce and what

you should be producing (noticing the gap).

There is a guide to

noticing on this site, linked below.

| Related guides | |

| noticing | for the guide to the a key learning and teaching strategy |

| Chomsky | for the guide to a very influential language theorist |

| learning styles | to see how the (so-called) theories about how people learn are sometimes used to plan |

| motivation | for an essentials-only guide to this area |

| first- and second-language acquisition | for a more technical guide to some of the main theories about how we acquire language(s) |

References:

Lightbown, P and Spada

N, Factors affecting second language learning, in

Candlin, C and Mercer, N (Eds.), 2001, English Language

Teaching in its Social Context, Abingdon UK: Routledge

Lightbown, P and Spada N, 2013, How Languages are Learned

(4th ed.) Oxford: Oxford University Press