N ticing

ticing

There's nothing particularly new about the concept of noticing. Teachers have long developed ways to draw their learners' attention to particular aspects of grammar, lexis, meaning, style, register, notion, communicative function and so on on which they want them to focus.

|

Types of noticing |

There are two:

- Noticing aspects of the language to which you are attending – noticing the language.

- Noticing the difference between what you hear or read and what you produce – noticing the gap.

|

Types of knowledge |

There are two types of this, too:

- Explicit knowledge is shown when a learners

can apply the rule and can also state the rule they are applying.

For example a learner says:

The window was broken by one of the girls

and not only constructs a correct sentence but can explain how a passive is formed with the verb be, where the agent comes in the sentence and how it is introduced by the preposition by. - Implicit knowledge is knowledge of the

correct form without the ability (without conscious effort) to

state what the rule is.

For example, a learner may be able to produce something like:

I'll come if you like

without being able to explain why the first verb phrase is formed with will and the infinitive and the second is a simple present tense of a stative use of the verb like.

One purpose of raising learners' ability to notice language is to

make the implicit explicit and the explicit automatic.

The reason for the first part of this is that the ability to

articulate a rule allows a learner to be able to construct an

almost infinite number of parallel utterances because, as the term

rule implies,

the structure is regular and predictable.

The reason for the second part is that once a rule has been

acquired, it can be applied almost without conscious thought because

it has been internalised. That makes the learner more fluent,

more able and more natural.

|

Some theory:Learning vs. Acquisition

|

As the headings suggest, there are four theories underlying the encouragement of noticing in the classroom.

|

Theory #1: Acquisition vs. learning |

A central tenet of Krashen's view is that there is a distinction

between learning (a conscious process of rule gathering) and

acquisition (an unconscious, natural process of learning which comes

almost without effort). For more, see

the guide to

Krashen and The Natural Approach, linked in the list of related

guides at the end.

There are many, however, who do not agree and take the view that

learning a language is a conscious process and noticing is part of

that.

|

Theory #2: Input + 1 |

Another of Krashen's hypotheses concerns the nature of the input

to which a learner is exposed.

The argument here is that, for optimum effect, the input a

learner receives should be a) comprehensible and b) just above the

level of the learner. This is sometimes abbreviated to INPUT +

1 or just i + 1. Many see this as an intuitively correct hypothesis for if

the input is incomprehensible, no sense can be made of it and no

learning can take place but if the input is below the learners

competence, they are not challenged to improve, given the

opportunity to acquire new

language or notice the gap between his / her own production and the

heard / read models.

|

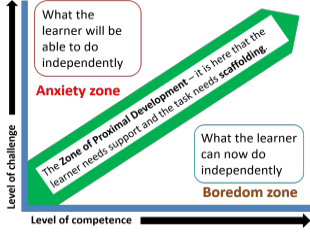

Theory #3: The Zone of Proximal Development |

The ZPD is a construct developed by Vygotsky and concerns the

optimum place in which learning happens. It may be defined as

a task or challenge which the learner can successfully complete with

only a small input from a more knowledgeable other.

Below this zone, the learner is not challenged, learning little or

nothing and becoming bored.

Above this zone, the learner is over-challenged, learning little or

nothing and becoming anxious and frustrated.

It looks like this:

|

Theory #4: Guided discovery / Discovery learning |

Later theorists have tied the idea to scaffolding which is the

process by which a teacher (or other more-knowledgeable other) may

lead a learner to a new skill or new knowledge by filling in a small

gap in the learner's ability.

For example, there is little point in presenting a very low-level

learner with a complex third conditional form such as:

If I hadn't invited her she would have been upset

and hoping that she or he will magically absorb the structural

nature of the clauses by noticing how they are constructed.

That will not happen. However, if we present a learner who can

already form a correct sentence in this style with something like:

If I hadn't invited her she

MIGHT

have been upset

then there is a good chance that the learner will not only notice

how the modal auxiliary verb is used but also how it affects the overall

meaning of the sentence.

This is because the learner is operating in the Zone of Proximal

Development and the task is not too easy (so the learner will not

benefit or get bored) and not too difficult (so the learner will be

overwhelmed by the data and become anxious).

Guided discovery, incidentally, also applies in mainstream

non-language-teaching methodology and refers to asking learners to

do their own research to discover what it is they need to know.

The term ‘guided’ refers to the fact that the teacher’s

responsibility is to direct learners to the most useful sources of

information rather than making them find their own way.

Also slightly incidentally, we should distinguish between

independent discovery learning in which the learners are left alone

to complete a task and find the data they need until it is time for

feedback and assisted discovery learning, which is what most people

understand by the term guided discovery, where the teacher is

involved throughout the process.

Noticing, then, is often a form of scaffolding of the learners'

efforts to help them move forward, incrementally, from the known to

the unknown.

There is a fuller guide to scaffolding and the ZPD linked in the

list at the end.

|

Input vs. Intake |

Underlying all the following is the distinction between input (the information the learner is exposed to) and intake (the information the learner actually assimilates). The argument is that without conscious noticing of language, intake simply doesn't happen. In other words, it is not possible to learn a language unconsciously.

Overall, Ellis sums up the arguments like this and suggests that:

the distinction between conscious

'learning' and subconscious' acquisition' is overly simplistic.

It is clear that 'acquisition', in the sense intended by Krashen,

can involve some degree of consciousness (in noticing and noticing

the gap).

Ellis 1994:363

He goes on to say that one possibility

is that explicit knowledge functions as a facilitator, helping

learners to notice features in the input which they would otherwise

miss and also to compare what they notice with what they produce.

Ibid

What learners are becoming aware of in this analysis is the possible affordances that the language input offers. By affordances is meant the possible uses one sees in the phenomena one experiences and the input one perceives. Just as we may see more than one affordance of a fist-sized rock (paper weight, weapon, hammer etc.) so we may see uses in the language we are exposed to.

For example, if a learner notices on one occasion that the adjective

bored forms the comparative and superlative forms with

more and most rather than adding -er or -est

to the stem as most single-syllable adjectives do and then notes the

same phenomenon with the adjective tired, he or she may

latch on to an affordance and hypothesise, correctly, that all

adjectives, regardless of length which are formed from the past

participles of verbs will follow the same rule. Then the

noticing will have the effect of allowing the learner accurately to

produce

They became even more lost

rather than

*They became even loster

|

Salience |

It is not certain, of course, that any two learners will notice the same things. What is noticed depends on the direction of attention and the salience of the information: its usefulness to the learner as an affordance. For example, from a piece of language such as:

Peter, being in charge for the moment, decided that this was the most important job

a learner who is focused on syntax may extract the fact that a relative

clause containing the verb be may be reduced by ellipting

both the relative pronoun (who) and the verb (was)

without affecting the meaning. To do that, she has to

reconstruct the sentence mentally as:

Peter, who was in charge for the moment,

decided ...

She may also notice, if primed

to do so, that this is different from the way her language does

things and the way she uses relative clauses in her own output.

She has noticed the gap.

Another learner, whose attention is on meaning, may note that the non-finite verb form (being) may be used to provide background information to the verb decide.

Yet another may notice that the verb be can, in fact be used in the progressive form and that contradicts information already given by a teacher that we do not use the verb in the continuous or progressive aspect. Another gap has been noticed.

What is noticed depends on two things;

- The affordance (i.e., usefulness that the learner perceives in the information)

- The direction of attention (on forms, meaning, aspect and so on)

The first of these can be estimated from experience, the second can be exploited deliberately.

What is noticed will depend to a large extent on what philosophers of language (and other things) call the learner's Umwelt which means the set of affordances (potentialities) that is perceived. In Dennet's terms, these are:

the things [the] agent should have in its ontology, the

things that should be attended to, tracked, distinguished, studied.

The rest of the real patterns in the flux are just noise ...

(Dennett, 2017:128 [emphasis in the

original])

The trick to using noticing, if there is one, is to filter out

the noise and leave the potentially useful information in focus.

|

Another way |

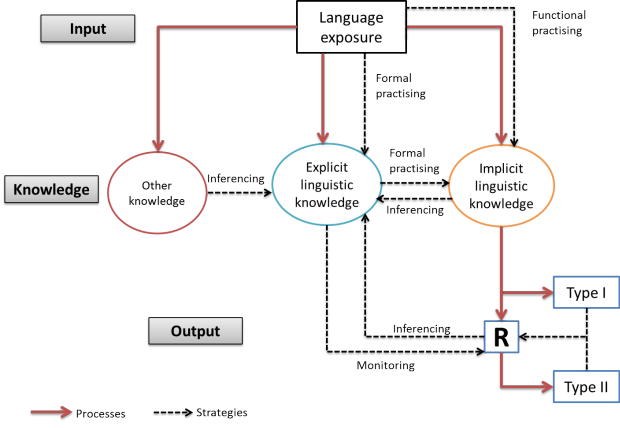

There is one theory of learning that neatly combines the ideas of subconscious and conscious learning with notions of implicit and explicit knowledge as well as showing the relationship between learning and acquisition. It looks like this (from Bialystok 1978:71). Look at the model and try to figure out what is going on. When you have some answers, click on the diagram for an explanation.

|

And it needs a little explaining, doesn't it?

|

Naturally, such a grand theory of language learning has not been without its critics and the model has undergone and will, no doubt, continue to undergo further changes. However, the central ideas of implicit vs. explicit knowledge and the learner's ability to inference between them have not been seriously challenged.

|

Noticing in the classroom (and beyond it) |

If you have come this far, you will have appreciated the need to encourage our learners to notice language they receive as input and also to notice the gaps between their output and the language they see and hear. What we are talking about here is:

- input enhancement (making the target item stand out in some

way)

or - input flooding (devising presentation material in which the target item occurs multiple times)

Input enhancement and input flooding may, of course, be used together for even greater effect.

How do we do this? Here are some ways.

|

The use of colour |

In any text,

it is possible to draw learners' attention

to what they

should be noticing as the focus

of the teaching and learning cycle so, for example,

in this text all

the prepositions are highlighted

in bold red font to draw the learners' attention

to the forms you

want them to notice. It's a simple trick but one which

in many people's

experience brings rewards.

You will have noticed the prepositions in that text which

are the targets of your noticing. It is almost impossible to

ignore them when they are highlighted

in red but easy if they are not in red.

Any class of function words, conjunctions, pronouns, determiners,

modal auxiliary verbs etc., can

be

treated this

way.

|

Being clear and explicit |

Teaching a form in class is half the battle (or less) and needs

to be backed up with explicit noticing of the form by the learners

in other settings. So, for example, if you are teaching

obligation forms or the meaning of must it pays off to

make sure your class bring into school examples that they have read

or heard of the forms in use (e.g., Bicycles must not ..., No

parking, No smoking, It is against the law to ..., Please do

not ... etc.)

Equally, for example, when handling a difficult concept such as the

so-called second conditional, it pays to make sure that learners

listen out for it in your own speech or that of speakers of English

whom they encounter and notice and record what they hear.

|

Working on receptive skills |

Learners cannot notice what they don't hear, read or understand so it

is important that we pay attention to receptive skills to provide

them with the ability to hear, read and notice what more able or native

speakers say and write. That way, when they are in any kind of

interaction, or reading a text of any kind they can be saying things to themselves such as

Oh,

I see, the stress is on the last syllable, I would have said that

this way ...,

That interesting, the word can be used to mean ...

etc.

|

Avoiding cognitive overload |

There is some evidence that if learners have to focus on form and

meaning simultaneously, then intake may be reduced rather than

enhanced and if you go along with that theory, you need to separate

them in your teaching to give learners the space to notice one or

the other.

That does not mean that it is necessary to handle form before

meaning or vice versa: the ordering you choose will depend on a

number of factors, including

- The complexity or otherwise of the form – the more complex the form, the more necessary it is to separate noticing its peculiarities from noticing its communicative effect. This is especially the case when your learners' first languages are dramatically different in terms of form from English.

- How obvious the meaning is – if the setting is explicit and no ambiguity is likely to arise, meaning can be handled easily before form. However, with targets such as complex modality and subtle nuances of meaning, it is important that meaning is dealt with without your learners having to struggle with figuring out the form simultaneously.

|

Input flooding |

Once is never enough in terms of noticing. If you really want input to result in intake, learners have to be flooded with noticing opportunities. Adapting or constructing texts in which the target language occurs repeatedly is one way of doing that. Authentic texts do not usually exhibit this so it is a reason to construct specific materials for noticing tasks.

Learners may be led to notice something on Monday and have

completely forgotten about it on Tuesday morning. For

input to become intake, and for an item to become embedded in

long-term memory, data have to be processed in some way, by, for

example, saying aloud what we have heard or writing what we have

read – and doing it more than once. This is sometimes

called rehearsal and retrieval.

Some have suggested that a minimum of nine separate exposures to an

item may be required.

|

Demanding tasks |

Tasks which demand the use and understanding of the target forms will be more effective than those in which the learner can use alternatives so task construction needs to bear that in mind.

If, for example, you want to focus on unreal conditional forms, make

sure that the practice materials require the use of the forms as in

If I were a ... etc. which is just about the only possible structure

to talk about something you are not.

The issue here is avoidance. Many learners will be tempted to

avoid the use of certain language items for a number of reasons,

including

- Because they are intrinsically difficult – the form of the third conditional or perfect modal auxiliary verbs such as He couldn't have been driving that fast etc. are examples of structures often avoided simply because they are structurally and phonologically difficult (/hi ˈkʊdnt əv bɪn ˈdraɪv.ɪŋ ˈðæt fɑːst/).

- Because the learner is unsure of the appropriacy of the item to perform a communicative function – making the settings and roles of participants clear is important or learners will be unsure of style and avoid the item altogether.

- Because you have risk-averse learners who see error of any kind as face threatening and will stick to what they know is right rather than risk making a public error.

|

Gap-fill tasks |

Setting a listening task with a text containing gaps where the

target form occurs forces learners to listen specifically for what

you want them to notice. This is not the same as a testing

procedure; it is a real noticing activity.

Another noticing activity is to give learners a text in which there

are differences between what is heard and what is read. If the

items you target are those which your learners currently avoid for

some reason (see above), this can be an effective way of getting

them to notice the gap between what they say and the target forms.

Another is a dictogloss activity in which learners are tasked with

reconstructing a text (rather than writing it down as they hear it)

after the text has been presented. Dictogloss activities focus

explicitly on noticing the gap because the eventual comparison of

what they have written with the original will often show the places

where the learners' production differs from a model.

|

Salience and input enhancement |

This is a question of focus.

Whichever type of teaching approach you favour, be aware that

learners will only easily notice that which is made explicitly

important. Underlining,

colour,

highlighting etc. are all

worthwhile techniques as is the use of voice tone, volume and so on.

This applies not only to teaching the formal systems of the language –

it is centrally relevant to skills teaching. Learners need not

only to employ a skill, they need also to be able to say what skill

they are using and why.

The simple technique of setting aside time at the end or after a

phase of a lesson for the learners to reflect on and

articulate what they have encountered so far is effective

in making the target more salient and memorable.

Learners' ideas of what the targets of a teaching routine are may

well differ from the teacher's idea unless you have some way of

forcing attention where you want it to be.

That can be done by, for example,

- Setting up buzz groups in which the learners try to identify what they have learned.

- Getting everyone to stand at the end of a lesson and, in turn, to state one thing they have learned before they can leave (effective with, e.g., teenagers).

- Getting the learners to select and rank the most important things in the lesson from a mixed list of central and peripheral issues.

- Compelling learners not only to use a specific sub skill to achieve a task but also to articulate the nature of the subskill they have employed.

|

Problematizing |

One common but arguably underused stimulus to noticing is

deliberately making something a problem. That may seem

contradictory but is, in fact, a rather simple procedures which

requires learners to notice a language item or phenomenon that they

have hitherto not been aware of.

For example, if asked to visualise (or sketch or identify) a picture

of:

Deer in a forest

and

A deer in a forest

learners may at first be mistaken in thinking that the images will

be very similar because they have not noticed up until now that

words for animals are often not marked for plural in English.

The word deer is extreme in this case, having no marked

plural form at all (which is not the same as saying it has no

plural). Words for other animals may have plural forms (fish

is an example) but the form is only used when specific numbers or

special types are being considered.

| The first sentence should conjure up an image like this: |

|

| and the second, an image something more like this: |

|

It is only when learners have, so to speak, been led down the garden

path into making the error that they can notice the issue.

Another example might be to play the same trick with:

A shop selling coffees

and

A shop selling coffee

where the mass vs. count use of the noun can be explicitly noticed.

A further way of using the down-the-garden-path approach might be to

alert learners to the usual way of forming plurals in English

(adding -s or -es) and then, once they have

managed to form the correct plurals of a range of nouns, such as:

bag → bags

leg → legs

class → classes

match → matches

etc.

to ask them to pluralise this set:

pony

foot

calf

handkerchief

potato

etc.

In being led down the path to error, the theory is that learners

will have problematized the issue and be more aware of the

subtleties of morphology in this respect. Correction will,

therefore, result in noticing.

At a more advanced level, for example, asking learners to complete

the following with a second logical clausal complement can be

instructive:

She didn't need to do it ...

She needn't have done it ...

because the first implies something like

... so she didn't bother

and the second implies

... but she went ahead anyway

As Ellis (op cit. p 640) reports:

First, Tomasello and Herron suggest that the 'garden path' technique encourages learners to carry out a 'cognitive comparison' between their own deviant utterances and the correct target-language utterances. Second, they suggest this technique may increase motivation to learn by arousing curiosity regarding rules and their exceptions.

The first of these suggestions is another way of saying that the technique helps learners to notice the gap.

A great range of specific language phenomena can be brought to

learners' attention in this way and it is particularly helpful in

getting learners to notice irregularities or marginal cases of

language use.

| Related guides | |

| Krashen and the Natural Approach | for the guide to this set of hypotheses |

| how learning happens | for a general and simple overview |

| second-language acquisition | for a guide to some current theories |

| scaffolding and the ZPD | this guide discusses how noticing can lead on to the shaping of learners' output by locating learning in the Zone of Proximal Development |

| Bloom's taxonomy | this is a way of classifying and grading the cognitive demands of tasks and activities |

| input and intake | for an obviously related guide |

| inferencing | for more on a related and important learning skill |

| unlocking learning | this is a guide in the Delta section which considers four theories including noticing and their classroom implications for learning |

If you would like to test yourself, there is a noticing exercise on all of this. Click here to go to it.

References:

Bialystok, E, 1978, A theoretical model of second language

learning, Language Learning 28: 69-84

Ellis, R, 1994, The Study of Second Language Acquisition,

Oxford: Oxford University Press

Dennett, D, 2017, From Bacteria to Bach and Back, UK:

Penguin Random House

Krashen, S, 1982, Second Language Acquisition and Second Language

Learning on-line version available at

http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/sl_acquisition_and_learning.pdf.

Schmidt, R, 1990, The role of consciousness in second language

learning. Applied Linguistics 11: 129-58.