Four ways to unlock learning potential

There isn't a word in English to describe something midway

between a method and a technique. Procedure is the best we can

find.

The term is slightly misleading because these are not procedural

techniques like drilling, nominating, waiting and so on. Nor

are they purely teaching behavioural formulae such as concept

checking or Dictogloss.

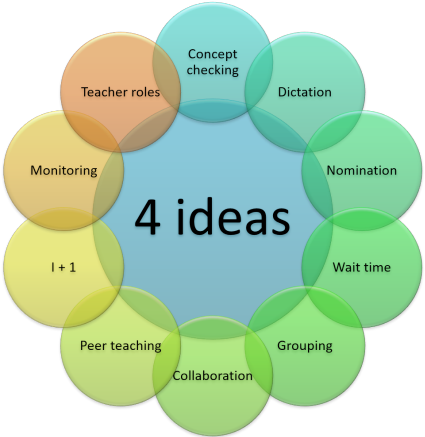

The four procedures, for want of a better word, described here

underlie a good deal of teacher behaviours in the classroom which

can lead to real learning.

|

Why these four? |

Good question.

There is, of course, a very large range of possible procedures and

techniques which good teachers use appropriately to enhance learning

in the classroom.

Some are managerial issues such as grouping learners effectively,

nomination, drilling, concept checking, instructional language,

questioning and so on.

Others are purely techniques such as eliciting, dictation of one

kind or another, using games, using music, song and poetry, schemata

activation, warmers and so on.

What is special about these four is that they are at one stage

removed from pure technique because they are the reasons why the

technique is employed.

It can be envisioned like this:

The graphic is intended to show that these four ideas lie at the

heart of much good teaching (not all of it) and are surrounded by a

cloud of second-level behaviours which depend on one or more of the

key ideas. The outer ring is meant to be indicative rather than exhaustive.

If you have taken an initial training course, you may well be

familiar with all the techniques in the outer ring because

second-level behaviours such as the ones listed above constitute a

good deal of what participants on such courses learn about and

should be

able to employ in the classroom. Many are taught by

demonstration and modelling followed by imitation by the trainee.

However, rarely mentioned on such courses is why the techniques are

being employed at all because such courses are usually short and

staunchly practical with little time or interest to discover deeper

reasons why we do the things we do in the classroom.

One reason why this guide is in the Delta section, although it is

linked from elsewhere, too, is that an essential difference between

initial- and diploma-level training lies precisely in investigating

what underlies good practice.

These four top-level ideas are:

- Noticing

- Input vs. output

- Inferencing

- Scaffolding

All four depend on four overarching hypotheses to do with learning and we'll summarise those first to set the scene.

|

Overarching hypotheses |

It has not gone unnoticed by most language teaching professionals

that learning only happens when the learner is ready for it to

happen. Most teachers have experienced times when they know

that what they are doing is not working in the sense that, although

the learners may seem busy, involved and active, nothing new is

being acquired.

At other times, the golden classroom moments, we have also been

aware that what is happening is contributing to real progress.

Learners are moving on, almost visibly, from where they were towards

where they want to be.

Underlying this phenomenon are four connected hypotheses concerning

what happens when people learn.

|

This is not to do with grand theories of

motivation concerning, for example, the difference between

intrinsic and extrinsic motivation or between instrumental

and integrative motivation. For that, see the guide to

motivation linked in the list of related guides at the end. Here, the concern is based more on the individual's understanding of what is useful and usable. There are three related elements:

This is the basic starting point for learning. If valence, expectancy and instrumentality are all low, learning is unlikely to happen no matter how entertaining and interesting the lesson is. |

|

This is a key concept and describes where the learners' current

language mastery stands on a scale from knowing nothing of the target

language to complete mastery. Diagrammatically, it can be pictured

like this:

In other words: without a knowledge of where the

learners' interlanguage is, we can't set sensible aims for

anything:

lessons, tasks, questions, activities etc. |

|

This is a cognitive

theory of learning and the one which will, for the most

part, be accepted here. The theory rests on the assertion that learners of a language are actively hypothesising what its rules are and refining their hypotheses as more data become available. It explains, among much else, the fact that second language learners may apply a newly-acquired rule indiscriminately and, for example, put and -ed ending on all verbs to show past tenses before they refine the hypothesis and link the phenomenon only to regular verbs in English. It will also explain errors such as *Do you can come? as evidence that the learner has made a hypothesis that all verbs form questions in this way in English. Only later will the learner reconstruct the hypothesis to exclude modal auxiliary verbs from the scheme. Evidence for this includes what is called the U-shaped learning curve. It has been observed that learners will often begin with the correct form and say, e.g.: I went to the party but will later produce: *I goed to the party because before they acquired the rule, they merely reproduced a chunk of heard language but, having learned the rule they applied it too widely. Later, they will grasp the rule's limitations and revert to the correct form. What follows assumes that learning is not a matter of imitation and repetition (although that may play a role) but an active cognitive process in which the learner is engaged not passively receiving. There is more on this in the guide linked below. |

|

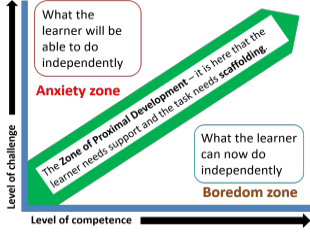

The ZPD is the Zone of

Proximal Development and the word proximal implies that it

is the zone in which the learner is closely approaching mastery

of any skill or language item and just needs a small amount

of help from a More Knowledgeable Other (which can be the

teacher, a peer or even a coursebook writer) to take the

next step to learning. The assumption is that learners need to be operating in the ZPD in order efficiently to learn. It can be pictured like this:  Step outside it to the right where a task is too easy and learners will learn nothing and be bored. Step outside it to the left where the task is too difficult and learners will become anxious and overwhelmed and be unable to learn. Staying in the green zone means that learning and teaching are happening in the most useful place and learners are being neither over- nor under-challenged. There is more on this in the guide linked below. |

These four mega-hypotheses underlie all that follows here and reference will be made to them after each discussion.

In what follows, we shall not be focusing on how to encourage

noticing, how to make input into intake, how to help people to infer

meaning or how to scaffold tasks and smaller learning units.

For that kind of information, refer to the links at the end to each

guide to the four areas.

Here, we are looking at what underlies the choice of approach or

procedure, not what the procedure involves.

|

Noticing |

It has been asserted, famously by Krashen, that language may be

acquired by an unconscious process of 'picking it up' and there are

those who would assert that they have, indeed, done just that.

Krashen's point is that acquisition is a process similar to the way in which children

acquire their first language(s). It requires meaningful and

frequent interaction in the language in which the speakers are not

focused on form but on meaning.

This is not to say that Krashen dismisses instruction altogether

because he goes on to state:

The classroom is of benefit when it is the

major source of comprehensible input.

Krashen, 1982

and elsewhere, he makes it clear that for lower-level students,

the classroom may be the only place where comprehensible and useful

input is obtained.

Learning is, however, a formal procedure which focuses on the

explanation of rules and correction of language form and Krashen

states:

When acquirers have rich sources of input

outside the class, and when they are proficient enough to take

advantage of it (i.e. understand at least some of it), the classroom

does not make an important contribution.

Ibid

Ellis, reviewing this, points out that:

It is clear that 'acquisition', in the sense intended by Krashen,

can involve some degree of consciousness (in noticing and noticing

the gap).

Ellis 1994:363

He goes on to say that one possibility ...

... is that explicit knowledge functions as a facilitator, helping

learners to notice features in the input which they would otherwise

miss and also to compare what they notice with what they produce.

Ibid

There are, as Ellis notes above, two forms of noticing:

- Noticing features of the language that you need to learn

- Noticing the difference between what you produce and the target with which you are presented

If Krashen is right that all that is needed for language

acquisition to occur is meaningful and frequent interaction in the

language in which the speakers are not focused on form but on

meaning, then deliberately encouraging noticing has no place.

However, if Ellis is correct and one of the major functions of the

teacher is to act as a facilitator and help learners to notice

salient input, then it certainly does have a place.

There is guide devoted to noticing on the site, linked below, but

here we are concerned not with the how and what of noticing but the

when, why and where.

All of the mega-hypotheses outlined above play a role here:

- Motivation

- Noticing will not be effective, however cleverly it is

encouraged, if the learner is unconvinced that the language or

skill which is the target is useful, relevant and central to the

learner's aims.

In other words, the targets of noticing must be explicitly linked to the learners' perceived needs and contribute to the notion that what is being pointed out, by whatever means, will help him/her to use English successfully. - Interlanguage

- Without a good understanding of where a learner's current interlanguage lies between zero knowledge of the target language and full mastery, it is not possible to identify what should be noticed and what can safely be ignored because it is either already part of the learner's competence or so far beyond the learner's abilities that the time is wasted because there is simply too much that needs to be noticed.

- Active construction of grammar

- This concerns what the learner does with the what he or she

has been encouraged to notice.

Noticing the gap, for example, becoming aware that a more natural way of saying:

He will perhaps not come

could be

He might not come

will allow the learner to perceive the gap between his/her production with the clumsy perhaps clause and the smoother model using the modal auxiliary verb. However, if language is not learned by a process of refining internally constructed rules, the time is wasted, of course.

Noticing the features is a parallel event. A learner who is encouraged to notice the tense structure in, e.g.:

I had my house painted

may be able to construct an internal grammar which includes some kind of clause-parsing mechanism such as

Ah, I see, it is past tense of have + the object + past participle of the main verb and means that I got someone else to do it.

This will, however, not happen unless the next condition is also fulfilled. - Is it in the learner's ZPD?

- The nature of the ZPD means that the learner must be led to

notice not all and every feature of the language but the

features which are of concern just above his or her current

level of ability. Too obvious and nothing is learned, too

obscure and nothing is learned.

This means in the classroom that tasks need to be set which encourage the learners to notice the features that contribute to an incremental small step (i.e., lie within the zone of proximal development) and all that is required is a small nudge in the right direction.

|

Input and Output |

The concept of input is perhaps the single most important

concept in second language acquisition. ... In fact, no

model of second language acquisition does not avail itself

of input in trying to explain how learners create second

language grammars

Gass, 1997:1

Note the comment that

learners create second language grammars.

The key premise is that learners do not

acquire a second language by a process of repetition practice or

drilling. The assumption here is that learners take an active

part in learning by:

- developing hypotheses based on the language they hear and read

- testing these hypotheses against the reality of new input

- refining the hypotheses to match the new reality

In other words, second-language learning is a cognitive process involving, as we saw above, the active construction of an internalised grammar (and more). Nearly all second-language acquisition theorists would concur with that, incidentally.

Input refers to all the target language that the learner reads

and hears.

intake refers to the part of input which the learner comprehends and

acts on to develop his or her development of an internal grammar of

the target language, the interlanguage.

We can already see how the input-intake hypothesis is closely

related the mega-hypotheses outlined above.

There is a fuller guide to the notions of input and output, linked

below. Here a summary of the mechanism which is proposed will

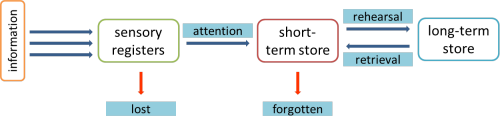

suffice. A pictorial view of what happens, based on Kihlstrom, is presented by Schmidt:

To explain:

- The sensory registers accept data from a number of sources, primarily what we hear and what we read. If we pay them no attention (as we might pay no attention to a passing car while we are watching TV) no memory is retained at all. The information is lost.

- If we do pay attention to the data (i.e., notice what we read and hear actively), the data are placed in the short-term memory store (also called working or primary memory).

- Finally, the data have to be processed in some way in order to remain in long-term memory and one way of doing that is to produce what we have heard, write what we have read and so on. That is what is meant by rehearsal and retrieval.

Here's how the four mega-hypotheses impact on this notion of how input becomes intake:

- Motivation

- If the input we receive is obviously irrelevant and

peripheral to the kinds of language we think we need, we will

pay less or even no attention to the data. Input, in other

words stalls at the starting grid.

The second question in the summary of expectancy theory outlined above is:

Does the learner believe he/she can successfully learn English from this input and these tasks?

If the answer is no, the process goes no further and the input is ignored.

The obvious classroom implication is to make the materials which we present as engaging and relevant as possible. Making materials and their contents relevant is not just a motivational factor or part of what has been called edutainment. It is a critical factor in ensuring that input is treated with enough attention for it to have a chance of becoming intake. - Interlanguage

- A good understanding of where a learner's current

interlanguage lies allows the teacher to select input which is

targeted at the perceived gaps in the learners' interlanguage.

This is not just a matter of interest and engagement, it is also to do with selecting language in the input which will, incrementally, move the learners' interlanguage one step along to the right, towards mastery of the language.

The nature of the way in which input may become intake lies on the right of the diagram above and the process of rehearsal and retrieval needs to be carefully focused on the state of the learners' current interlanguage or the process will falter at best, collapse at worst.

Again, this point merges with the final one about the ZPD. - Active construction of grammar

- This concerns what happens when we encourage the process of moving from the short-term to the long-term memory store. The theory is that actively engaging with the language, making and amending or adjusting hypotheses, aids this process because rehearsal and retrieval can only be achieved if the language is cognitively processed. That means active construction of grammar, not just being told about it.

- Is it in the learner's ZPD?

- If the input is outside the ZPD, then, again, the process

falls at the first hurdle. Overly simple or overly

difficult input means that the learners are operating

outside their ZPDs and not processing the language at all either

because it is boringly simple or intimidatingly difficult.

Attention may be present, especially in motivated learners but, if the material is outside the zone, the language cannot be recorded even in the short-term memory and it certainly can't be processed in a way that allows it to enter the long-term store.

|

Inferencing |

Inferencing involves making logical deductions based on data to

which we are exposed. For example, if you are standing in a

railway station on Platform 6 and you hear:

This is the 4:45

you will probably, and probably rightly, infer that this means that

The train which is on this platform is the

one timetabled to leave at 4:45

you don't need to have it spelled out for you because the other data

around you tell you that the utterance is not referring to a bus, an

aeroplane, a meeting or a horse race.

There are two main reasons why inferencing is an important skill to

practise:

- No user of a language can possibly know all the words, structures and expressions in the language so we have to infer meaning from what we do know.

- Very few texts, whether spoken or written, actually contain all the information we need fully to understand them. Speakers and writers will always assume some prior knowledge in their hearers and readers.

We infer from three general sources (although each can be subdivided as the guide to inferencing, linked below, makes clear.

- Extra-linguistic sources:

These include:- knowledge of the world

this was what you used to understand the train announcement - knowledge of people's motivations

this is how you figured out that the announcer had some data to impart - knowledge of roles in society

this is how you knew to trust the message you heard

- knowledge of the world

- Intra-linguistic sources:

These include:- lexis

we will expect any text, written or spoken, to include terms related to its subject so, when reading a recipe or listening to a platform announcement, we will expect to find terms such as mix, cook till done, chop, oven, pan, eggs etc. and platform, times, depart, arrive, numbers etc. respectively and will not be primed at all to hear or read rhinoceros, spade, carburettor, seaside or surgery etc. - structure

we can assume from our general schema to do with texts that the essential information will be presented in a predictable order with a recipe listing ingredients before procedure and a train announcement telling us what the train is before giving times and platform numbers. This is called our generic knowledge of information staging of texts.

- lexis

- Inter-lingual clues

These are mostly to do with words or structures which have cognates in other languages.

For example, if you are a Germanic language speaker then words like land, drink, is, garden, sea, ship, fruit and so on will not be mysterious or hard to decode. Equally, if your first language is Romance in nature then words like operation, amplifier, contradiction and express will be equally transparent to you.

For the most part, too, structures such as comparatives, determiners and quantifiers will also be accessible at least receptively.

On the other hand, if you are a speaker of a non-Indo-European language such as Japanese, Mandarin, Arabic or Thai such resources will be far less available and functionally absent.

There's no doubt at all that the ability to infer is something that needs attention in the language classroom although there is ample evidence to assume that people do this kind of thing all the time in their first languages and hardly ever think about it.

However, here too, the influence of the mega-hypotheses can be felt.

- Motivation

- If the input we receive is too poor to make sensible

inferences from it, then motivation will be a factor.

Asking people to guess what something might refer to without providing them with adequate data to do so is frustrating for them and ultimately dysfunctional.

Asking people to infer meaning at all is, in some circumstances, something that needs careful handling.

The third question in the summary of expectancy theory outlined above is:

Does the learner believe the learning will help him/her to use English successfully?

If the answer is no, because a learner is not (yet) convinced that guessing is a useful procedure, then the lessons to be learned from inferring in any way will be lost. - Interlanguage

- A good understanding of where a learner's current

interlanguage lies allows the teacher to imagine what is and is

not actually inferable from the data that are present.

Clearly, if the level of a learner's vocabulary does not allow prediction of terms which might appear in a text, then he or she will not be alert enough to spot lexical chains or be able to infer what the lexis might actually mean.

Again, this point merges with the final one about the ZPD. - Active construction of grammar

- Inferring from context is not always a reliable procedure

because learners can, and often will, form hypotheses about the

language they are presented with which are false. This

wastes time and cognitive energy because the hypothesis has to

be discarded, rather than adjusted, if it is too far adrift from

reality.

For example, if in a recipe one encounters:

slice, chop, fry and then grate the vegetables

a learner might assume that fry is just another way of cutting vegetables (based on knowledge of slice , chop and grate) and miss out an important step.

The hypothesis about the meaning of fry then has to be discarded because it is too far from the truth to be usefully amended. - Is it in the learner's ZPD?

- If the input is outside the ZPD, then, again, the process

fails because there is either no need to infer the meanings

because

the language is familiar and the task lies to the right of the

ZPD illustrated above or there simply isn't enough familiar

language from which sensible inferences can be made and the task

lies to the left of the ZPD. Either way, the effort to

encourage inferencing has failed.

Inferencing only works at all if a task lies firmly in the green zone.

|

Scaffolding |

As the guide to scaffolding, linked below, makes clear, there is a good deal more to it than just helping or assisting learners to reach their targets. It is an active process inextricably linked to the notion of the Zone of Proximal Development.

In brief, scaffolding involves six elements (based on Wood, Bruner and Ross 1976:98):

- recruitment: gaining the learners' attention to what the target is and encouraging them to believe it is important to them

- reduction in degrees of freedom: simplifying the task by reducing the number of constituent acts required to reach solution

- direction maintenance: keeping the learner motivated and on task by chopping up the task into doable sections

- marking critical features: helping learners to notice the gap

- frustration control: the teacher's assistance should make the acquisition of the target language or skill less, not more, stressful than working alone

- demonstration: presenting an idealised version of the language you want the learners to acquire. (It may also involve demonstrating part of a task but not all of it, in order to make the task doable at all.)

This is a long way removed from the loose way in which the term scaffolding is coming to be used in English Language Teaching where it seems, rather too often, to be a synonym for helping or supporting. The key difference is that scaffolding is a consistent, active process which involves collaboration between teacher and learner to shape the emerging language.

Here, too, all the mega-hypotheses play a role.

- Motivation

- This impinges on the first and third elements of scaffolding

set out above.

Learners need to believe that being helped and supported to reach the targets is a better (or at least no worse) way of proceeding that simply being told the right answer. The object is to raise their interest in and commitment to tasks.

It may, for example, involve the teacher making it clear that polishing and improving their production will make them more effective speakers or writers in English or convincing them that the target item is worth learning.

In other words, it addresses the second motivational question:

Does the learner believe he/she can successfully learn English from this input and these tasks?

Point f. above is also affected by issues of motivation but less globally. We are talking here of task motivation in terms of frustration control. The teacher's assistance should not be so overbearing as to remove all motivation to work on the task and not so minimal that the learner feels as if he or she is floundering. It's a narrow line to walk. - Interlanguage

- Scaffolding is all about moving learners incrementally along

the interlanguage cline between zero knowledge and full mastery.

If you don't know where they are on the cline, this can't be

effectively done.

It also involves incremental, small steps, not huge leaps. The object of scaffolding is to provide just enough assistance and no more to allow learning to happen.

Again, this point merges with the final one about the ZPD. - Active construction of grammar

- Part of the hypothesis is that learners are continually revising

and revisiting their hypotheses about how the language they are

learning works. That is what is meant by active

construction.

The task of scaffolding is to aid this process, not by presenting data that fly in the face of everything the learner thinks she or he knows but by presenting data which can be used to revise a hypothesis even if only very marginally. A marginal step along the interlanguage cline is better than falling off the ladder altogether. - Is it in the learner's ZPD?

- Scaffolding relies on a careful identification of the ZPD.

It cannot work at all outside the green zone illustrated above.

Point d. above refers to salient features and these are only salient if they are limited to one or two extra skills or pieces of knowledge that the learner needs to complete the task satisfactorily. Any more than that and you are encouraging guesswork, any less and no learning is happening at all.

Scaffolding comes in many guises and may involve partial demonstrations (as opposed to models to follow slavishly), direction (as in helping learners to know where to look in texts for specific data), supplying partial answers to tasks and so on. It is not so much the what of scaffolding that is important but the how and why.

|

The level of challenge |

Underlying what has been discussed in this guide is a fifth principle: getting the level of challenge right. If, as is frequently assumed, learning occurs when people make connections between what they already know and new data then the level of challenge is crucial. Too little and no new connections can be made, too much and connections can't be perceived.

Challenge is not only to do with the difficulty of the language

or skill which learners are required to master, i.e., the level at

which one is teaching. It is also to do with the cognitive

effort that the learners are asked to expend on a task.

In particular, the work of Bloom and many others in the area of

designing a taxonomy of educational objectives is influential and

informative.

Very briefly, the revised taxonomy measures the level of cognitive

challenge as follows:

- Level 1: remembering

This involves simply the ability to recall a fact. For example, that the past tense of undertake is undertook. - Level 2: understanding

This involves some deeper thought to get to grips with a fact. For example, that certain items or events have characteristics in common. For example, that there are some simple (and not so simple) rules about how to form comparatives and superlatives of adjectives. - Level 3: applying

This involves using knowledge and understanding to make a decision. For example, knowing that a lion is a carnivorous animal, understanding what that means and applying it to being cautious in approaching the animal. In language-learning terms, this means applying a rule you have acquired to more examples of the language to see if the rule is working. - Level 4: analysing

This requires the application of levels 1 to 3 and then going on to breaking things down into constituents to understand fully what is happening. For example, breaking complex noun phrases into understandable and classifiable constituents or being able to recognise the different forms of multi-word verbs are both analysis tasks. - Level 5: evaluating

This involves using all the processes in levels 1 to 4 and judging how well, for example, one's use of language measures up to the models with which one has been presented. It may also require the learners to evaluate the level of formality they need to aim for in certain settings or the level of formal accuracy that is required. - Level 6: creating

This is the most demanding level of all because it requires the use of the previous 5 levels in order to synthesise data into a new and original work. This, obviously, requires independent and quite sophisticated language use but it is simultaneously a high-demand cognitive process for which people need adequate preparation if a task is to be completed to their and others' satisfaction.

For a more detailed consideration of Bloom's taxonomy and its various revisions, see the guide, linked below.

|

What's the relevance to Delta? |

There is a difference, fairly easily discernible in a classroom by an observer, between a competent but undertrained teacher and a very good teacher whose practice is firmly based on principles. The former is someone who

- knows how to use some noticing techniques

- can provide some comprehensible input just above the learners' current level

- can help learners to infer meaning

- can assist them when they are doing tasks or asking questions

The latter, however, is someone who can do all of that and:

- knows when and how to use these techniques appropriately

- is aware of the level of cognitive challenge that tasks present

- and understands the difference between:

- being told and noticing

- being exposed to language and getting usable input

- inferring and guessing

- helping and scaffolding

This is what assessors often mean when they write something like

This candidate is a good teacher at an initial training level but not quite there yet at Delta level.

You, of course, need to fall into the second category and that

means not only applying the techniques but understanding them and

being able to select them appropriately and use them effectively.

That is much more than mastery of technique.

Now, if you care to, you can use the links below to find out more.

| Related guides: | |

| motivation | for more on concepts of motivation including some of the above and much more |

| interlanguage | this concept is described in the guide to handling error in the classroom |

| active construction of grammar | this underlying theory is discussed along with and in contrast to other theories of second-language acquisition |

| Krashen and the natural approach | for more on some very influential hypotheses of the role and place of the classroom |

| Bloom's taxonomy | the six-level categorisation of cognitive challenge and achievement |

| scaffolding and the ZPD | for more on the ZPD and its links to the ideas of scaffolding (and distinguished from helping and support) |

| noticing | for a fuller guide to this area of classroom technique |

| input | for the fuller guide to the distinctions and connections between input and intake |

| inferencing | for much more on how we do it and how we can practise it in the classroom |

| methodology refined | this is a longer guide which attempts to place approaches, methodologies, hypotheses, procedures, techniques and classroom solutions in some kind of framework |

References:

Ellis, R, 1994, The Study of Second Language Acquisition,

Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gass, SM, 1997, Input and interaction in second language

acquisition, Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum

Krashen, S, 1982, Second Language Acquisition and Second Language

Learning on-line version available at

http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/sl_acquisition_and_learning.pdf.

Krathwohl, DR, 2002, A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview,

Theory into Practice, Volume 41, Number 4, College of Education, The

Ohio State University

Schmidt, R, 1990, The role of consciousness in second language

learning. Applied Linguistics 11: 129-58.

Vygotsky, L, 1962, Thought and Language, Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press

Wood, D, Bruner, J and Ross, G, 1976, The role of Tutoring in

Problem Solving, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol.

17, 1976, pp. 89 to 100, Pergamon Press