Input and intake

|

The concept of input is perhaps the single most important

concept in second language acquisition. ... In fact, no

model of second language acquisition does not avail itself

of input in trying to explain how learners create second

language grammars Gass, 1997:1 |

Note the comment that

learners create second language grammars.

In all of what follows, the key premise is that learners do not

acquire a second language by a process of repetition practice or

drilling. The assumption here is that learners take an active

part in learning by:

- developing hypotheses based on the language they hear and read

- testing these hypotheses against the reality of new input

- refining the hypotheses to match the new reality

In other words, second-language learning is a cognitive process. Nearly all second-language acquisition theorists would concur with that, incidentally (but many do not).

|

Input and Intake |

There is a key distinction between these two terms:

- input refers to all the target language that the learner reads and hears

- intake refers to the part of input which the learner comprehends and acts on to develop his or her internal grammar of the target language and its rules of use

It has been assumed by some that input alone is sufficient to

develop second-language ability and those who have picked up a

language simply by listening and reading what is around them in its

native-speaking setting may well concur. The key distinction

for our purposes, however, is whether input becomes intake

unconsciously or whether a conscious process of noticing and acting

on the input is required for it to become intake.

Here we have to follow a small theoretical diversion.

- Input becomes intake unconsciously

-

This is one of the central tenets of Krashen's distinction between learning and acquisition. As he puts it: -

Language acquisition is a

subconscious process; language acquirers are not usually aware

of the fact that they are acquiring language, but are only aware

of the fact that they are using the language for communication.

The result of language acquisition, acquired competence, is also

subconscious. We are generally not consciously aware of the

rules of the languages we have acquired. Instead, we have a

"feel" for correctness. Grammatical sentences "sound" right, or

"feel" right, and errors feel wrong, even if we do not

consciously know what rule was violated.

(Krashen 2009:10) - There is a separate guide on this site to Krashen and the Natural Approach, linked in the list of related guides at the end.

- Input + active noticing becomes intake

-

Noticing is discussed in an article by Schmidt (1990:138) in which he identifies three issues:

(1) the process through which input becomes intake, related to the issues of noticing and subliminal perception - (2) the degree to which the learner consciously controls the process of intake, the incidental learning question

- (3) the role of conscious understanding in hypothesis

formation, the issue of implicit learning.

Schmidt doubts, in fact, whether learning can happen at all without conscious noticing and intent. He concludes: -

subliminal language learning is impossible, and that intake is what learners consciously notice

Op. cit.:149 (emphasis added)

These two standpoints cannot be easily reconciled because

Krashen's position is that acquisition, rather than mere learning,

occurs unconsciously and Schmidt's position is that this is

impossible. To support his assertion, he discusses the way in

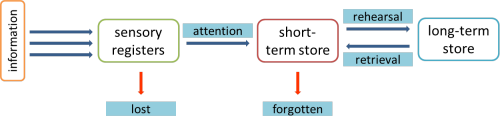

which information is processed. A pictorial view of what

happens, based on Kihlstrom, is presented by Schmidt (op cit.):

To explain:

- The sensory registers accept data from a number of sources, primarily what we hear and what we read. If we pay them no attention (as we might pay no attention to a passing car while we are watching TV) no memory is retained at all. The information is lost.

- If we do pay attention to the data (i.e., notice what we read and hear actively), the data are placed in the short-term memory store (also called working or primary memory).

- Finally, the data have to be processed in some way in order to remain in long-term memory and one way of doing that is to produce what we have heard, write what we have read and so on. That is what is meant by rehearsal and retrieval. Without this, items are deleted very quickly, in a matter of seconds, from the short-term memory store.

About the only ground on which both theories agree is that the input, however it is processed, has to be comprehensible to the learner.

|

Processing input into intake |

Learners will, theory has it, identify input worth noticing because there is a communicative intention behind the data. Someone is trying to communicate something so it's not just noise.

The question remains to discover what happens in the learner when she/he is consciously converting input into intake. In this process, the learner will be noticing one of two things and may be noticing both at the same time:

- Noticing the gap: the difference between the input data and

the language the learner can produce.

For example:- I pronounce the word comfortable as /kʌm.fɔː.ˈteɪb.l̩/ but my teacher just said /ˈkʌmf.təb.l̩/. I need to adjust how I say this word. I'll write it down now.

- I said:

A fire is in the forest

and the person I spoke to said

Did you say, "There's a fire in the forest"?

I need to remember to use the There is formula to sound more natural. I'll try saying it now.

- Noticing the form: the way in which the input data exemplify

how the language should be used. For example:

- I heard some people talking and one said:

Let the kids go early

and the reply was

I allowed them to go early yesterday

so, let is not followed by to + the infinitive but allow is. Hmm. I'll make a note and try to remember that. - I read:

We discussed the matter fully at our last meeting. We do not need to talk it over again.

So, the verb discuss does not need a preposition and we can use a separable phrasal verb talk over to mean the same thing. I'll make notes.

- I heard some people talking and one said:

The assumption is that we have mental language-processing mechanisms to deal with these issues. It has been described like this:

What happens to learners is that as they encounter

input, their internal mechanisms begin to make connections between

formal features of language and the meanings they encode. The mechanisms responsible for syntax

work on these data to establish the nature of the syntactic rules

the language has.

(VanPatten and Wong, 2003:408)

The reason this occurs is to do with an internalised knowledge of language that we all possess: Universal Grammar. As an example, a learner encountering a language in which the verbs are heavily marked for person, number, gender and tense may note the fact from only one or two examples but, once alerted to the fact that this is an inflected language, the learner will be primed to notice further inflexions and apply a cognitive process to figuring out the system and its exceptions.

|

Is learner output learner input? |

In traditional classrooms, learners have been encouraged and in some cases forced to produce language from the outset. Input-based theories do not require that. In fact, Krashen and Terrell's Natural Approach explicitly confirms the fact that learners should only speak when they feel ready to do so.

Output from learners is not input to the learning process:

- It cannot, by definition, be above the current level of the learner.

- Output from other learners is often flawed and a poor target

for useful noticing. Swan (2005) puts this rather forcefully:

If one was seeking an efficient way of improving one’s elementary command of a foreign language, sustained conversation and linguistic speculation with other elementary learners would scarcely be one’s first choice. - Even in a conversation-driven approach, such as Dogme, output from other learners will only form a small part of input worth processing as intake, and proponents of the approach will refer to the texts and other language-rich materials that learners can bring to the class.

- Task-based approaches in which learners cooperate to achieve a task are often cited as times when learners can absorb language from each other, effectively, peer teach. That this may sometimes happen is not in doubt but that it is the most efficient way of learning language and getting input that can be turned into useful intake most certainly is arguable.

- Language drills in the classroom may well be a way of the

teacher inserting new input but, because it is clear that it is

a drill and not a communicative act, the language will not be

noticed in the same way.

The fact that a teacher believes that something needs drilling is an acceptance that most if not all the learners are producing flawed language in some way, structurally or phonologically. If this is the case, encouraging learners to listen to each other, by drilling only parts of a group at a time, for example, is positively counterproductive.

Language worth noticing is language produced by someone who wants to communicate something.

|

Affordances and information theory |

Affordance theory originates from the work of the American

psychologist James Jerome Gibson (although others have attributed it

to ecology) and focuses on the perceived possibilities in the

environment.

For example, when you see the door handle above you are probably

aware that its main affordance is that pressing it down will open

the door but there are other affordances that will occur to you

(such as making it a place to hang your clothes, an attractive

decoration in its own right, something you can

pull without pressing and so on).

The more immediate and obvious the function is, the more efficiently

something has been designed (a principle that is, or should be,

close to the hearts of software designers, of course).

It is assumed that when a learner looks at a text or hears some

language (wherever it originates), the main affordance of the text

should be clear, i.e.

This is something I can use as input and convert into intake.

An example might be the language produced by other learners

during a classroom conversation (such as might appear in a Dogme

approach). If this language is perceived to have an obvious

affordance in terms of being useful and noteworthy input, it may be

used for that purpose but, if the affordance that is perceived is

merely that it is language already mastered being used to express a

mildly interesting thought, attention will fade.

In other words, output from other learners will often be ignored.

If, on the other hand, the output comes from the teacher and is

focused on language the learners clearly do not master (yet), then

its main affordance, providing the language has been carefully

designed, will be obvious:

This is language I need and can

incorporate into my repertoire.

Salient information

An allied point concerns the perceived usefulness of the information that

is carried by the input: its saliency.

For example, if, on seeing someone pushing a wheelbarrow full of

earth across a garden, we can readily notice that the wheelbarrow is

carrying a load of something, earth in this case. However,

that is not the only information being carried. Depending on

how primed we are to notice important information, we may also

perceive that the event contains the data concerning the

labour-saving nature of wheelbarrows and that may be the most

important information if we, too, are concerned with moving heavy

materials around the garden (or anywhere else).

So it is with language.

A learner may, for example, use the information contained in a

clause such as the first one in:

While watching the

game, I noticed that the referee was biased against Margate

United

to understand that the noticing happened during the game and that we

do not know at which point it occurred exactly. That is in the

nature of the non-finite clause.

Another learner, concerned more with syntax than meaning may note

something completely different. For example, that it is

possible to ellipt the subject and the primary auxiliary verb (I

was in the first clause) because the items are common to both

clauses or easily understood from the co-text.

A third learner may extract the information that non-finite

participle clauses can be used as time subordinators and a fourth

may learn something about the meaning of the word biased

and its dependent preposition (against).

What is noticed will depend on the direction of attention and the

information the hearer / reader already has or wants to get.

|

Classroom implications |

So, what we need to do is provide rich, comprehensible input, help

our learners notice the salient features and let them do the rest,

right?

Not quite. There are some issues for classroom

practice:

- Comprehensible input

Krashen asserts that input should be comprehensible (and few dare disagree) but at just above the learners' current level of control. Unfortunately, this begs some questions:- What constitutes 'comprehensible'? Is this input 10% above the learners' level, 20% or what? What level of comprehension is required for the input to be converted to intake?

- Whose comprehension? Most teachers teach groups and their abilities in both reading and listening may vary very widely. One learner's comprehensible input in terms of reading text may be another learner's mystery and one learner's listening comprehension may be another's misery.

- The solution seems to be to contrive input that is comprehensible in terms of the targets rather than wholly comprehensible. There may be surrounding language which is not immediately comprehensible to everyone but, providing the language which contains the targets of instruction is comprehensible, input can convert to intake.

- Rich input

Most writers in the field recognise that rich language input is needed to help learners encounter and notice the patterns of the language they are learning. If one only ever encounters a single genre, a single register or a single style with a narrow topic range, the data simply aren't there to help the process. There is a serious issue here, too:- Overly rich input may

disguise the very phenomena we want the learners to notice

because the richer the input, the less frequently in

proportion the items will occur.

Having to read 300 words to encounter two uses of a particular tense form is not an efficient use of learners' time. - The solution is to

strike a balance between richness and focus. Texts

need to be graded, and probably quite contrived at lower

levels, to ensure that the targets are salient enough to be

effectively noticed and processed.

Maintaining naturalness is something of a challenge but can be achieved with care and thought.

- Overly rich input may

disguise the very phenomena we want the learners to notice

because the richer the input, the less frequently in

proportion the items will occur.

- Targeted input

Many will also agree that it is the teacher's role to manipulate input to select stretches of language that contain something worthy of noticing but which happens to be at the right level. However,- It is not easy to select or alter texts in a way which allows this because the result is often an unnaturally densely packed text or one which contains too few of the examples of the form.

- A solution is to

adjust the text so that the targets are in some way

highlighted. With written texts, this can be done by

highlighting sections,

varying font size

and colour and so

on.

With spoken texts, this is more challenging but pre- and while-listening tasks can be devised which force learners to focus on the language targets in the text. For example,

Listen and write down the words John uses to make polite requests to his boss.

This time, listen to how the boss responds and write what language she uses exactly.

Packing texts with numerous examples of the targets is known as input flooding and making the targets stand out in some way is referred to as input enhancement, incidentally, and there's a bit more to this in the guide to noticing, linked below.

- Noticing is self-selecting

One strength of an input approach to teaching is often noted as being that it allows the learners to pay attention to the language they need in their setting and for their purposes (as well as their level). However,- This may work with sophisticated adult learners with clear learning aims but will not be effective with younger learners (who may have no current need for the language) or for those with vaguer and less concrete aims and purposes.

- A solution is to

raise awareness in the learners of where their productive

ability falls short of their language needs. A

Test–Teach–Test approach is often effective in this regard,

as is a task-based tactic.

Obliging the learners to deploy their current interlanguage to achieve a communicative outcome, and then noting the gaps between what they can do and what they need to be able to do is often effective.

These are not insurmountable problems, of course, but their solutions need some thought and care, especially concerning what input is provided and what exactly the learners are being asked to notice and turn into intake.

| Related guides: | |

| noticing | a separate guide concerning how to turn input into uptake |

| The Natural Approach | Krashen and Terrell's approach |

| Some alternative approaches | a guide which includes approaches such as Total Physical Response, Dogme and others |

| The Lexical Approach | a guide to an approach which focus on lexis rather than grammar |

| Chomsky | a guide to some of Chomsky's most influential theories |

| syllabus design | the design of a syllabus often reflects a view of the best approach to teaching it |

| unlocking learning | this is a guide in the Delta section which considers four theories of learning and their classroom implications |

| first- and second-language acquisition theory | an overview of the theories of how we acquire our first and learn a second language |

References:

Gass, SM, 1997, Input and interaction in second language

acquisition, Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum

Gibson, JJ, 1977, The Theory of Affordances, in Shaw, R

& Bransford, J (Eds.), Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing,

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Krashen, S, 2009, Principles and Practice in Second Language

Acquisition, Internet

Edition

Krashen, SD & Terrell, TD, 1983, The natural approach: Language

acquisition in the classroom, London: Prentice Hall Europe

Schmidt, R, 1990, The role of consciousness in second language

learning, Applied Linguistics 11: 129-158

Swan, M, 2005, Legislation by Hypothesis: The Case of

Task-Based Instruction, Applied Linguistics, 26 (3): 376-401.

VanPatten, B & Wong, W, 2003, The Evidence is IN: Drills are OUT,

Foreign Language Annals, Vol. 36, No 3, pp403-423