First and Second Language Acquisition Theories

What's the relevance of First Language Acquisition to teaching an additional or second language?

Good question. There are a number of reasons we should know a little about First Language Acquisition (FLA, in the trade):

- It provides a kind of benchmark for theories of Second Language Acquisition (SLA). The theories are parallel in many ways.

- A good deal of methodology in SLA has been premised on the theory that we will acquire a second or additional language in the same way we acquired our first language(s).

- The way the human brain operates in language learning is not radically different (so some theories assert) whether we are learning our first or additional language(s).

At each stage in what follows, we'll be considering how theories

of first language acquisition are relevant to teachers of additional

languages.

Here, then is a run-down of some major theories and hypotheses

concerning how people acquire their first language(s).

|

Innateness: language is in our genes |

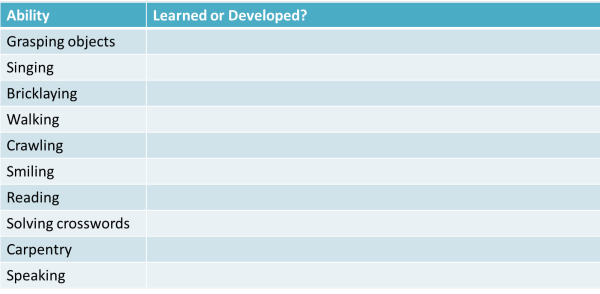

You were not born with the ability to speak, ride a bicycle, play the piano, type, play chess, walk or dive for pearls. What concerns us here are the abilities you naturally develop as opposed to those which you are taught.

Some of this is quite easy. Divide this list into learned

(i.e., taught or self-taught) abilities and those which naturally

develop in all normal children:

Click on the table when you have done that.

It is clear that some behaviours, such as the ability to grasp

objects or walk are biologically determined because all children,

regardless of their culture, learn to do it pretty much at the same

stage in their development. For example, most babies learn to

sit, then roll over, then crawl and finally walk between the first 9

to 12 months of life (some take a bit longer and some skip the

crawling bit, preferring a bottom shuffle). None, however, has

to be taught the skill.

Babies in all cultures learn to talk between 18 and 28 months of

life.

Some behaviours are never naturally acquired so if you never learn

to ride a bicycle or play a decent game of chess, you will not

magically develop the ability to do so, no matter how long you live.

The question for this guide is whether using language to

communicate is in the same category as walking or the same category

as playing the piano.

This has fairly profound implications but don't expect the

definitive answer here.

|

Biologically controlled behaviours |

Aitchison (1989:67 et seq.), drawing on Lenneberg, suggests there are 6

characteristics of biologically determined behaviour. As you

look through the list, ask yourself whether speaking a language meets each of the

criteria.

Then click on the

![]() to reveal some comments.

to reveal some comments.

| The behaviour

emerges before it is necessary |

Children use language before they need it.

Children are fed, clothed and looked after well into life (sometimes until well after puberty). Children do not need language to survive. What is surprising is that language develops at more or less the same stage in life regardless of the culture. |

| The behaviour

appears without the individual making a conscious decision |

A child does not, it seems clear, suddenly decide to

learn a language.

Individuals may decide to learn other skills, such as bricklaying or playing the flute, but these skills are clearly of a different order from speech. |

| The emergence

of the behaviour is not triggered by external events

(although the environment needs to be sufficiently rich for

it to develop) |

Children begin to talk even when their immediate

environment is unchanging. They live in the same

place with the same people, eating the same food and

doing pretty much the same things.

The trigger, if there is one, seems to be something internal in the child's development. And that can only be a development in the brain because, physically, there is no reason why a six-month-old baby shouldn't be able to talk perfectly well. On the other hand, however, as the tragic tales of feral children or those brought up isolated from other people demonstrate, language cannot adequately develop without a rich environment with plenty of data for the child's brain to work on. |

| Direct

teaching and intensive practice have relatively little

effect |

If you are learning to lay bricks or play the oboe,

it is quite likely that the amount of teaching and

practice you get will be directly related to your

eventual skills level.

Not so with language, it seems. Although carers often make explicit efforts to correct children's language production, the evidence is that it has almost no measurable effect. The pointlessness of overt correction has been noted by numerous researchers. (Aitchison 1989:69) Practice, too, as we shall see, is not a determining factor in first-language acquisition. |

| There is a

regular series of milestones as the behaviour develops, and

these can usually be correlated with age and other aspects

of development |

All children seem to develop speech in the same way,

reaching certain milestones at approximately the same

age. For example, in English, children develop

word inflexions at around two years of age, and

questions and negatives slightly later. Mature

speech is generally achieved by around 10 or 11 years of age.

Moreover, there is a documented and researched order to which items in a language are acquired. For example, in English, it appears that, with minor variations, the progressive -ing structure, the plural -s and articles are acquired before the 3rd person -s, the regular past-tense endings and contracted verbs such as "she's a teacher". There is more on milestones below. |

| There may be a

critical period for the acquisition of the behaviour |

Again, some of the evidence for a critical period

for language acquisition (often cited as between 2 and

13 years of age) comes from tragic cases of brain

damaged or isolated / feral children. In such

cases, it has been noted that language development

proceeds much more slowly and may never result in fully

formed language skills.

This is, you should note, a very controversial area of research and theorising and has been for decades. |

|

Milestones |

Lending weight to the innateness theory is the often-observed

milestones which all children go through on their journey to fully

competent language use.

The usually cited milestones for first language acquisition are

as follows but evidence is not apparent that the same sequence is

observable in second-language acquisition. There are some

similarities but the parallels are not close.

| Age | Language stage |

| Birth to 3 months | crying, gurgling, non-speech noises |

| 3 to 6 months | babbling |

| 6 to 12 months | intonational babbling |

| 12 to 18 months | words and set phrases |

| 18 to 24 months | increasing vocabulary and rudimentary grammar |

| 24 to 36 months | inflexions and transformations |

| 36 to 60 months | approximation to adult speech patterns |

|

The evolution of the ability to process languageThere is, unsurprisingly, some debate among evolutionary biologists concerning how such a mechanism may have evolved. Recent genetical research is pointing to a set of genes including one called FOXP2 (pictured). It would be a gross oversimplification to

dub this 'the language gene' as much else, including the

interactions between this gene and a range of others, is involved in

the ability to process language. However, the gene appears to

be central to our ability to process and produce language and people

who lack it or in whom it is mutated or inactive cannot handle

language. There is a good deal more about theories concerning the evolution of language in the guide, linked below. |

|

Issues and objections |

Firstly, while there is strong evidence that some

language-learning ability is innate, a good deal of the theory

has been based on just one language, English. From that,

theorists of universal grammar have averred that the essential

building blocks of language structure are common across all

languages and that these items are what the language acquisition

device is aimed at: noun phrases, verb phrases, adjective

phrases and so on.

This ignores the enormous diversity of structural phenomena

across the range of some 6000 to 7000 languages on earth, many

of which are poorly if at all described. Some, it has been

persuasively demonstrated, get along quite happily without

adjective or adverb phrases at all, for example, choosing to

inflect the noun phrases or verb phrases instead.

Secondly, innateness theories fail, it has been argued, to explain the great differences between spoken and written language. If we are genetically programmed to learn language, whence come these differences?

Thirdly, innateness theories have been criticised as greatly underestimating the effects of culture and community on the language-learning process. In many languages, males and females speak differently and employ different grammatical structures and in some, children's language is substantially different from the language of adults. It is difficult to account for these differences on the basis of inheritance of language-learning abilities or pre-programming for language at all.

Fourthly, we need to ask how this innate program arose. If there is indeed a language learning module hard-wired into the brain of humans, how did it evolve? The genetic changes which would have had to occur are dramatic and it is difficult to see how they could have arisen gradually in the usual piecemeal fashion which evolution favours.

Finally, there seems to be some evidence that different language modules are acquired at different times and in different ways. Critics of the critical period hypothesis point to the fact that some language-deprived children well past the assumed critical period actually do manage to learn the lexicon and syntax of a language (although others don't) and it has often been noted that second-language learners can often acquire native-like vocabulary and syntactical abilities but may never acquire the phonological system of a foreign language.

Nevertheless, the conclusion that many have reached, based on the

evidence, is that the ability to acquire language is, indeed, innate

to humans (and only humans).

For a little more on that debate, see the guide to language

evolution, linked below.

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

There are a number of implications for ELT professionals, of course. They come down to the assertion that we should not assume that a second or subsequent language can be acquired using wholly different mental processes from the ones used to acquire one's first language. It is not, after all, as if human mental processes are fundamentally altered in any way as we grow up.

- teaching children

- If the innateness theories are right, then what is required

is simple exposure at the right time to a rich linguistic

environment rather than explicit instruction. Instruction

may, in fact, be counterproductive or, at least, pointless.

Teachers of children should also bear the acquisition order in mind and not expect or try to demand production of certain forms before the child is 'ready' to learn them.

Practice and correction, too, are pointless. - teaching older children and adults

- Again, if the theories are right, especially concerning the

critical period hypotheses, then we should not expect adults to

acquire language simply by exposure.

We should also expect them never to acquire wholly native-like production if instruction is carried out after the critical period. There is, indeed, some evidence to suggest that in pronunciation especially, older learners never acquire native-like production skills.

The influence of innateness theories is readily seen in some

methodological approaches which rely on rich input and exposure to

language alongside the abjuring of formal practice and instruction.

For more in this area, see the guides to

Krashen and the

Natural Approach and Chomsky, both linked below.

|

Imitation theory: I speak what I hear |

This theory rests on the fact that children speak the language(s)

in which they were raised. A child taken from an English-speaking

environment at an early age and raised in an Urdu-speaking

environment will acquire Urdu as its first language just as

indigenous children will. The child's genetic background is

wholly irrelevant.

The theory is that imitation must have a role to play because the

connection between a word's sound and form and its meaning is

arbitrary: you cannot infer the meaning of a word from its form so

you must hear it spoken in a clear context to be able to imitate its

use.

For example, you may know, through learning at an early age that the

word frog refers to a small amphibian creature but there is

nothing in the written or spoken form of the word that can tell you

that. All languages exhibit this sort of arbitrariness so the

same animal is represented as:

rana (Spanish)

broască (Romanian)

padda (Afrikaans)

granota (Catalan)

varde (Latvian)

żrinġ (Maltese)

and so on.

Unfortunately,

however, Imitation Theory explains little else of what we know about

language acquisition.

Bergman et al (2007:315)

They go on to explain three major problems with Imitation Theory. From reading what has been said above, what are they? Click here when you have an answer.

- Children's speech is different from adults' speech

Children do not produce fully formed sentences. The evidence is that they progress from 1-word utterances (acquired around 12 months) to 2-word utterances (around 18 months) and then go on to more complex utterances with longer sentences until they start to make rare or complex constructions around 5 years of age.

Indeed, children will often reduce an adult's statement to comply with their current productive capacity. On hearing, for example, something like The train goes through the tunnel an 18-month-old child might reduce it to Tunnel train and an even younger child might reduce it to one imperfectly formed word such as trai'. Children routinely reduce what they hear to conform to their current Mean Length of Utterance or MLU. - The U-shaped learning curve (see below)

If imitation were all there was to acquiring language, then the U-shaped curve, going from correct production of irregular forms to overgeneralisation of the rule to recognition of the irregularity (e.g., from went via goed and then back to went) simply would not occur because a child would very rarely, if ever, hear the incorrect form in order to imitate it. Children must, therefore, be actively forming hypotheses about language structure. - Innovation

Both children and adults are capable of forming utterances they have never heard. In fact, the number of possible utterances in a language approaches infinity. A child might, for example, say Cow river fall even though no adult has ever said it to her. Adults, too, produce language never before heard. For more, see the guide to Chomsky, linked below.

|

The U-shaped learning curve |

This refers to a phenomenon which has been frequently observed

and researched.

English exhibits a number of irregularities in inflexions, notably

the changing of the middle vowel or consonant to make a past tense form (as in

make-made, buy-bought rather than *maked, buyed

etc.) and in irregular

plurals (such as child-children, mouse-mice etc.)

Children often acquire the irregular form and then revert to an

inaccurate regular form before once more acquiring the irregular

form. So, for example, a child may produce The mice ran up

the clock, then begin to say The mouses runned up the clock

before settling on the correct version later.

If this is true, the importance is obvious: it means that language

cannot be being acquired by simple imitation and practice. If

it were, children would never produce something like *comed

instead of came for the simple reason that they would never

hear it. In other words:

There is not a shred of evidence

supporting a view that progress towards adult norms of grammar

arises merely from practice in overt imitation of adult sentences.

Ervin, (1964:172) cited in Aitchison

(1989:74)

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

A number of approaches to and techniques in teaching languages

appear to be based on the assumption that people learn language by a

process of imitation of a model.

Behaviourist-based approaches in particular, such as Total Physical

Response, Situational Language Teaching and audiolingualism

emphasise the need for learners to repeat (and be rewarded for)

correct models set in a clear context.

Why do you drill in a classroom if you don't believe imitation and

repetition are

effective?

If the aim is to reflect how a person's first language is acquired

and Imitation Theory is so flawed, then any methodology based on it

will be similarly imperfect.

|

Reinforcement Theory: praise, correction and reward |

The theory claims that children learn to produce correct language

because they are praised and rewarded (by adult approval) when they

do and are corrected when they don't.

It has, of course, close connections with Imitation Theory (because

correction demands imitation, for one thing) and with behaviourist

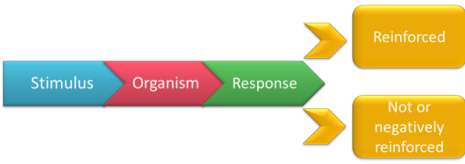

theories of learning. Behaviourist theories assert that

learning takes place by the alteration of habitual behaviour. Here's a

very brief summary:

- The process starts with a stimulus, say, a question from a carer such as Who did you see? put to the organism (in this case, a child). The stimulus can elicit a variety of responses but only the 'right' one will be reinforced.

- So, for example, if the child responds with I seed Tom the carer will negatively reinforce it with No, say I saw Tom.

- If, eventually, the carer can persuade the child to produce a correct utterance, the response will be rewarded (i.e., reinforced) with something like Oh! That's lovely! and the child will learn the form.

- Enough Stimulus > Response > Reinforcement cycles will see the habit instilled and the language acquired.

There are three fundamental problems with the

theory. From what has already been said, what are they?

Click here when you have an answer.

- Carers do not focus on form; they focus on content

For example, if a child produces a well formed but untrue statement, carers are more likely to correct it or at least avoid reinforcing it. So a true but incorrectly formed statement may receive praise and a correctly formed but untrue statement will receive censure of some kind. - Cuteness will be reinforced

Carers and other adults have frequently been observed reinforcing false structure and lexical use simply because it is cute and endearing. Thus Choo-choo Bang-bang! while meaningless, uncommunicative and poorly formed may produce a positive response in doting adults. - Even when adults do focus on correcting form, the research

shows that it is almost wholly ineffective. Here's an

example (from Bergman et al, op cit.: 316):

Note that the child is not producing random forms. The child is clearly operating to a rule but the rule differs from the adult's rule and direct attempts at instruction fail.Child: Nobody doesn't like me. Mother: No, say "nobody likes me". Child: Nobody don't like me. (repeated 8 times) Mother (now exasperated): Now listen carefully! Say, "Nobody likes me." Child: Oh! Nobody don't like me.

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

Much that is recommended in classrooms in terms of praising

learners and error correction is based (even implicitly) on this

kind of behaviourist theorising. It is a short step from

asserting that all learners respond positively to praise and that

praise motivates them to perform better to suggesting that

reinforcing acceptable language will lead to the instilling of

correct language habits.

In other words, a teacher wedded to a cognitivist view of learning

may be using the praise to motivate while one coming from a

behaviourist direction will be using praise to reinforce a response.

You can't tell by watching and it may be the case that the learner

is responding in one way, another way or both ways.

|

Active Construction of a Grammar Theory |

This theory "holds that children

actually invent the rules of grammar themselves"

Bergman et al (op cit.:316)

The theory is allied to Innateness theory insofar as the ability to

develop rules is presumed innate but the rules themselves will

depend on the structure of the language which children hear around

them.

It has been compared to a kind of switchboard effect which operates

on the data the child hears.

So, for example, a French child

will notice that in the language it hears, the adjective normally

follows the noun (un évènement fantastique)

and the switch for noun–adjective ordering will be thrown. A

child in an English-speaking environment will hear, by contrast,

a fantastic event and throw the switch the other way (for an

adjective–noun language). Enough exposure will result in the

switch becoming permanently fixed but French and English children

will still have to be aware of the restriction to the rule in order

to be able to produce un petit problème and the people

responsible correctly.

Such hypothesising about language form neatly explains the U-shaped

learning curve described in this guide. When first acquired,

the rule is applied indiscriminately and then it is later amended to

account for exceptions.

|

Issues and objections |

The theory, of course, depends on the assumption that small

children have well developed cognitive abilities and that is by

no means demonstrated by a number of studies. For example,

the ability to recognise that the length of an object is not

dependent on its position or that the volume of a container is

unaffected by its shape are not shown by very young children

(and indeed by all adults).

The fact, too, that all children seem to develop language in

more or less the same stages at the same ages would lead one to

believe that all children everywhere and in all environments

have exactly the same cognitive ability to form

and amend hypotheses about language as they hear it spoken

around them. That is not borne out by the data.

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

If learners (of whatever age) of a second or subsequent language are applying this kind of cognitive rule-forming behaviour to the language they encounter then concepts such as noticing and the positive role of error in the refinement of language theory in the minds of learners become even more important. See the guides to noticing and to error, both linked below in the table of related guides, for more.

|

Connectionist Theory |

Connectionist theory is based on the assumption that as we learn,

we create neural connections in the brain which reinforce the

learned behaviour.

For example, if a child encounters the word mouse in

relation to operating a computer frequently, the connection between

computer control and a mouse will be formed and the more often the

word is met in this context, the stronger the connection will

become. If, later, the child encounters the same word as

descriptive a small, furry rodent, then a

different network connection will be made to accommodate the newly

discovered use of the word.

A problem for the Active Construction of Grammar

Theory is the starting point. That theory explains the

production of false items such as feets, He showeds me

or mouses as evidence that learner is making

overgeneralisations from rules imperfectly acquired in terms of

their restrictions.

Anecdotally, you may be able to think of the same phenomenon

occurring with learners of English as an additional or second

language.

However, when children are asked to make past tenses or plurals from

nonsense words which resemble real but irregular forms, they do not,

apparently, apply the grammar rules but respond in terms of

statistical likelihood. It is conceivable that, having learned

that the plural of mouse is mice that children

will assume that the plural of the nonsense word flouse

will not be flouses as active construction theories would

suggest but may opt instead for frice by analogy with

mouse-mice.

Another example (again, from Bergman et al), is that when asked to form

the past tense of fring, many children will suggest

frang or frought (by analogy with ring and

bring etc. respectively) rather than the structurally

predictable fringed. In some varieties of English, we

do indeed find, for example, the use of brung as the past

forms of the verb bring.

Hence, too, one might encounter a suggestion that the plural of

noot would (or might well) be neet not noots

and it is true

that many native speakers of English will prefer handkerchieves

as the plural of handkerchief by analogy with

wolf-wolves etc. and the status of roof-roofs/rooves

is unclear.

It has been suggested here that humans make neural connections in

the brain based on the frequency of what they hear rather than

making rules based on the structure of what they hear.

|

Statistical reasoning |

Another way to explain this process is to rely on inferencing (to which there is a dedicated guide on this site, linked below). It works like this:

If you are presented with the names of six horses in a race and

no other data at all, you would be correct in thinking that your

chances of backing the winner are 6:1 against, i.e., a roughly

16.67% chance that you would win.

However, if you are also told that of the six horses only number 5

has ever won a race before against similar opposition and that all

the others have finished last or second to last in their previous 3

races, you might adjust your expectation of which horse will win

based not on intuition or guesswork but on the statistical

probabilities the new data have supplied.

The theory is that human learning happens like that.

Now take the situation in which you are faced with trying to

decide what form of a verb will follow the verb arrange in

a sentence such as

I arranged __________ tomorrow

and the choices are:

- going

- go

- will go

- to go

- goes

- went

All things being equal, you might think that you have a one-in-six

chance of hitting on the right form. However, all things are

not equal because you already know that the following sentences are

correctly formed:

I hope to go

I agreed to go

I asked to go

I decided to go

I remember going

I recall going

I enjoyed going

The reasoning (which is mostly unconscious) goes like this:

- In all the correct forms I know, none takes the bare infinitive, the present with -s, the will + infinitive structure or the past tense so I can dismiss choices 2, 3, 5 and 6 for the moment.

- I now have a choice between alternative 4, to go, or alternative 1, going, as the correct form. Shall I toss a coin to decide?

- No. I also know that all the forms with -ing

that I know are correct are concerned with the past. I

already know, for example:

I remembered meeting her

I finished painting the doors

They admitted breaking the window

etc. are correct uses and I can see that the remembering, finishing and admitting all come after the actions of meeting, painting and breaking. - However, I can also see that the forms I know that are

correctly formed with a to-infinitive work the opposite

way around. I know, for example, that:

I hope to see her

I promise to come early

I expect to talk to her

are all correct forms and that the hoping, promising and expecting all come before the seeing, coming and talking. - Statistically, therefore, I will select:

I arranged to go tomorrow

because the arranging must precede the going.

and you'll be right, of course.

What you have done is apply probabilistic reasoning based on

your other knowledge of the language and assumed that, statistically

speaking, you'll be right to bet on the favourite.

Just as in horse races, of course, this will not always result in a

win (or bookmakers would all be out of business). If you apply

the same process to a sentences such as:

I look forward ____________ tomorrow

you will not get the right answer. An outsider has won the

race, in this case.

Dennett, 2017:269, puts it this way:

... the brain's strategy is continuously to create "forward models," or probabilistic anticipations, and use the incoming signals to prune them for accuracy – if needed. When the organism is on a roll, in deeply familiar territory, the inbound corrections diminish to a trickle and the brain's guesses, unchallenged, give it a head start on what to do next.

What we do next, of course, is understand and, if necessary, act on the linguistic data we are receiving.

It may also be the case that both Connectionist and Active

Construction of Grammar strategies are being deployed

simultaneously.

That is a conclusion to which many have arrived in the face of the

evidence for both theories which is slowly accumulating.

|

Issues and objections |

There are those who consider that the connectionist view of

language acquisition adds nothing substantial to the theory of

active construction of grammar. What it does is add

another layer of cognitive processing and there is nothing

within active construction theory that denies that.

The fact that all languages contain many examples of

non-intuitive and exceptional structures also presents problems

for the theory. We might assume, following the statistical

analogy approach, that all of the following are, for example,

allowable but children rarely, if ever, produce such forms.

If the brain is indeed forward modelling from data it already

has, why is that?

unsage (by analogy with unwise)

I look forward to see you (by analogy with I

want to see you)

I concealed behind the door (by analogy with I

hid behind the door)

I suggested to go out (by analogy with I

expected to go out)

However, the fact that adult learners do produce such forms

consistently provides some evidence that the connectionist view

has more relevance to the teaching of languages to adults and

the existence of analogy errors has long been accepted.

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

If the two approaches are being combined, in fact, by mature learners as well as children, there are some implications especially for how language is presented and which language is selected for presentation.

- Connectionist theories clearly have a good fit with approaches such as The Lexical Approach and focuses on collocation and colligation. If it is true that learners (of whatever age) are applying some kind of statistical analysis to the language data they are exposed to, then it makes sense to design materials which contain statistically likely rather than unlikely combinations of words and structures.

- Chunking of language, too, is important because chunks such as air conditioning + unit, steering + committee / wheel etc. lend themselves to the formation of neural pathways in the brain.

- Getting learners to notice connections in terms of

colligation will also be effective if connectionist theories

hold water. The acquisition of, e.g.:

I allowed him to go

Mary permitted him to come

I forbade him to speak

etc. will be facilitated if they are presented together and frequently encountered but presenting them alongside

I made him go

I let him speak

etc. will be positively counterproductive.

The same consideration would apply to all compare-and-contrast rather than notice-the-similarity approaches.

|

Social Interaction / Constructionist Theory |

This theory places great emphasis on the kinds of social

interaction in which people encounter language. The argument

is that it may be combined with both Connectionist and Active

Construction of Grammar theories to explain how the richness, or

otherwise, of the data the learners encounter will be exploited.

It seeks also to explain how it is that children slowly develop the

ability not only to use language accurately but also appropriately.

Theoreticians in this area focus a good deal of attention on what is

called child-directed speech. Such speech tends to be

delivered with excessive intonation range and pitch and to be

simplified and repeated for comprehension. From it, the child

learns to decode its meaning before going on to be able to

comprehend and produce more complex and appropriate adult-to-adult

language.

Bergman et al (op. cit.: 318) draw on Gleason and Ratner (1998) for the following example of child directed vs. adult speech:

- See the birdie? Look at the birdie! What a

pretty birdie!

(accompanied by high voice pitch and gesture)

vs.: - Has it come to your attention that one of our better-looking feathered friends is perched upon the windowsill?

The problem which immediately arises, of course, is that children do acquire the ability to produce and comprehend the second example, and they do it effortlessly and very quickly.

|

Issues and objections |

While interesting, there is little actual evidence that the

theory is sustainable. Intuitively, one might consider

that social interaction is vital for the development of

appropriate language use but that can also be explained by the

direct correction of children by adults when they produce

inappropriate language and by imitation theory.

That exposure to language in use is required for language

acquisition has never been in doubt. What role the nature

of the interactions between children and carers plays in the

acquisition of language is.

|

Relevance to (English) language teaching |

In terms of second-language acquisition, the theory states

that learning is constructed by the learners. This is

usually contrasted in educational theory with what is labelled

as a transmission model in which knowledge is handed down from

above.

The criticism of that is, naturally, that social constructivists

are setting up an unrealistic 'traditional' model in order to

suggest how social constructivism is superior.

It is, moreover, asserted that learning is primarily a social

activity. This means that knowledge and skills are not

acquired by individuals operating alone but only through

interaction with others.

This makes the theory a good fit with communicative classroom

approaches which forefront real communicative tasks and

emphasise interaction with peers and others.

Clearly, much of Communicative Language Teaching lays great

stress on natural and appropriate language as the target of

instruction and this theory sits well with such an approach.

The procedure of introducing simplified language and then refining

it for appropriate and accurate communicative effect lies at the

heart of such an approach.

Teachers, while not exactly producing typical child-directed

language often are observed to use unnaturally emphasised intonation

patterns and stress as well as a good deal of gesture.

It has sometimes been a criticism levelled at a communicative

approaches to language teaching that while the approach has a

well worked out theory of language, it is less certain about a

theory of learning. Enter social constructivism to the

rescue.

Unfortunately, the theory is somewhat silent concerning the

mechanisms through which learning takes place (unlike, e.g.,

connectionist and active construction theories). It may,

therefore, be wise to reserve judgement or, at least, to take

the view that while social interaction is undoubtedly a useful

and motivating factor in second-language acquisition, it cannot

be the whole truth or individual silent learning would be

impossible. If you are reading this page alone, is it the

case that you are unable to learn from it because you are not

interacting with others?

Such considerations have not stopped some from asserting that

social constructivism is the way in which learning

happens.

Here's an example:

We believe that learning is best

conceptualised through a social constructivist theory of learning. A key tenet of this is the view that learning

is constructed by the learner, as opposed to the traditional,

“transmission” model of teaching and learning in which knowledge is

passed on to students fully formed, ready to be assimilated.

Furthermore, learning is primarily a social activity – knowledge and

skills are constructed through interaction with others.

Harrison, 2019 (Senior Education Manager,

Cambridge Assessment English)

|

Are adults and children all that different? |

Well, it depends on the theory you accept, doesn't it?

It seems clear that concepts such as critical period only apply to children (and the evidence is there to suggest that adult learners have far more trouble learning an additional language than children do). Methodologies which purport, therefore, to be based on how a child learns and that such an approach is applicable to adults and more mature children should be handled with care and some scepticism because there is evidence that children and adults learn differently, not least because of their very different experiential backgrounds and because all normal adults have already acquired a perfect knowledge of their own language.

Other theories, such as Imitation and Reinforcement theories (the

basis of drilling and repetition and much else) as well as Active

Construction of Grammar, Connectionism and Social Interaction theory

may be just as applicable to mature learners of an additional

language as they are to immature learners of first languages.

The argument here is that we do not abandon or lose access to our

cognitive abilities as we mature. We may use the abilities

differently, some might argue more effectively, as adults.

If so, there are obvious consequences for the design of materials,

classroom procedures, error correction techniques and much else.

|

Differences between first- and second-language acquisition |

There is little doubt that the processes through which we learn our first and second languages are related. However, there are also critical differences. Here's a short list, based on Cook, undated, and on Ellis, 1994:107, drawing on Bley-Vroman 1988):

| Issue | First-language acquisition | Second-language learning / acquisition |

| Success | Normally, we learn our first language with 100% success. | Success is variable and some learners are clearly more successful than others. Achieving 100% success in acquiring a second language is vanishingly rare. |

| This, of course, rather depends on what is meant by success. The goals of first- and second-language learning are often very different so success cannot be easily compared. | ||

| Variation | All children learn their first languages in what appears to be exactly the same way and by going through the same stages. | Second-language learners may take a variety of approaches, either self-imposed or imposed by the setting in which they learn. |

| Goals | The goal of first-language acquisition is native fluency. | Second-language learners vary in their goals. For some, native-like fluency is not important and an adequate level of achievement may be reached long before anything approaching 100% mastery. Few second-language learners see native-level mastery as a realistic or necessary goal. |

| Motivation | A child's motivation is simply not a relevant consideration. | The level and type of motivation have been shown to have a marked effect on learning outcomes. |

| Fossilisation | Fossilisation is unknown in children's language development. | Second-language learners often cease to improve their mastery of the language and may even return to previous, lower levels of competence. |

| Intuitions | Children develop quite sophisticated intuitions regarding correctness. | Second-language learners are often not able to form intuitive judgements of correctness. |

| Instruction | For first-language acquisition to be successful, no explicit instruction is needed. | Most second-language learners have some instruction, either institutionally (in classrooms) or via self-help and reference resources such as dictionaries and grammars. |

| Correction | In first-language acquisition, studies have revealed that overt correction is neither required nor effective. | Most second-language learners respond positively to correction and try to take note of it to improve their abilities. |

| Affective factors | Providing only that the data are available in sufficient quantities, children's attitudes to learning have no effect or are simply irrelevant. | Second-language learning is heavily influenced by affective factors including attitudes to the classroom, the other members of a group (if any), the teacher, the materials, the institution and the target-language culture. |

Variation in how learning takes place is discussed below.

|

Healthy, critical scepticism |

This guide has been a brief one and only covered the salient features of a range of popular answers to the questions:

- How do people learn a language?

- Is the way that we learn / acquire our first language similar to the way we learn / acquire a second language?

Reality may be more complex than theorists will have us believe. The ways that learning happens are still obscure and work goes on with, occasionally, flashes of insight and new evidence to support one theory or another. This does not mean that the various ways in which learning may or may not happen are mutually exclusive. Some theories are presented as take-it-or-leave-it choices but humans are complex animals with the capacity for complex behaviour and ways of thinking about the world. To aver that all of them learn all facets of all languages in the same way is much more likely to be wrong than right.

It may turn out to be the case, for example, that we learn the grammar of our first language in one way and the grammar of a second or subsequent language very differently. We may learn to pronounce our first language by a process of imitation and repetition but learn the pronunciation of a foreign language by combining a deliberate cognitive process with some hard listening to spot the gap between what we produce and the native-speaker models we encounter. It has been suggested that we approach the acquisition of our first language very differently from the way we approach learning a new language and we may learn different facets of the new language in different ways. The suggestion, again briefly, is that:

| Target | First language acquisition | Second language learning |

| Grammar | By a process of setting a mental switchboard and using our language acquisition device to act on elements of universal grammar | By actively making hypotheses concerning structure and refining them as and when new data come to light and by extrapolating from the known to the unknown |

| Lexis and meaning | By attending to how words are used around us and developing mental pictures of what a word means | By connecting our experiences with the ways in which the target language describes the world, via translation when that's appropriate |

| Pronunciation | By hearing, imitating and repeating the sounds of adults around us | By noticing the gap between our efforts and the sounds of the models we are given and attempting to narrow it to an acceptable difference slowly and deliberately or by frequent repetition |

| Appropriate communication | By noting corrections from adults and imitating the ways in which they talk to each other and to us | By taking part in interactions with peers (often other learners) and focusing deliberately on issues of style and register in our own production |

If this is the case or even part of it is true, looking for a theory which explains all learning is a doomed undertaking. Worse, it will constrain teachers' behaviours and planning to a degree which will not be helpful to the learners.

| Related guides | |

| second-language acquisition | for a guide to some current theories |

| how learning happens | for a fairly simple guide to the area |

| language evolution | for the guide reviewing some major theories in the field and a little more on problems with innateness theory |

| inferencing | for a guide in which there is a little more about how humans use statistical reasoning to understand language |

| noticing | for the guide to techniques for encouraging learners to notice language and to notice differences between their language and what they encounter as models |

| error | for the guide which considers the types and sources of error and the development of interlanguage |

| Krashen and the Natural Approach | for the guide to a very influential idea |

| Chomsky | for the guide to a very influential theorist |

| types of languages | for a guide which sets out the structural ways in which languages differ |

There's a simple matching test on this area.

References and other sources:

An enormous amount of research, some of it focusing very narrowly

on the acquisition of particular structures,

is available to one who looks for it in the discussion of

first-language acquisition. Not all of it is

relevant to ELT.

Aitchison, J, 1989, The Articulate Mammal, London: Unwin

Hyman Ltd

Bergmann, A, Hall, K & Ross, S (Eds.), 2007, Language files:

Materials for an introduction to language and linguistics,

Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University Press

Cook, V, n.d., First and Second Language Acquisition Notes

available at www.viviancook.uk/SLA/L1%20and%20L2.htm

Dennett, D, 2017, From Bacteria to Bach and Back, UK:

Penguin Random House

Ellis, R, 1994, The Study of Second Language Acquisition,

Oxford: Oxford University Press

Harrison, G, 2019, Developing teachers: key principles in the

Cambridge English approach to teacher education, Cambridge:

UCLES, Professional development, Teaching (available at: https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/blog/developing-teachers

[accessed October 2021]

Todd, L & Hancock, I, 1986, International English Usage,

Beckenham: Croom Helm