The sentence: an essential guide

No, not that sort of sentence.

Note: if you don't know the difference between a subject and an object or your complement from your elbow, it may be wise to follow the guide to subjects and objects which introduces some fundamental concepts.

At some point, all approaches to English grammar take the sentence as a basic unit of language. But there's a problem:

|

What is a sentence? |

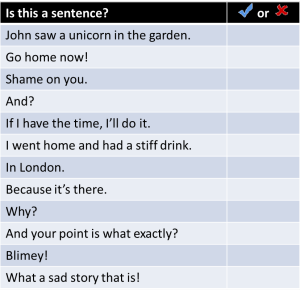

Of the following, which, to you, constitutes a sentence?

Click on the table when you have looked at each one and decided whether

it is a sentence in English.

Whether you had the same answers or not doesn't matter at this stage. Look again and decide for yourself what the criteria are to get a tick in the box. There are two essential criteria. Click here when you have decided what they are.

- A sentence must contain a finite verb (that is a verb with a tense or person marker)

- A sentence must contain a subject (usually a noun) which governs the verb

There's an exception to Rule 2 in the table. What is it?

Right. The sentence Go home now! gets a tick in the box but has no obvious subject. The subject of imperatives like this is usually implied in English.

Many grammars will use the term 'clause' instead of 'sentence'. There's a good reason for this which does not need to concern us here. All you have to remember is that a clause is a group of words containing a verb. So, for example, I'm going is a clause but on Tuesday is not a clause (it's a phrase).

|

Four sorts of sentence |

There are four types of sentence in English:

| Sentence type | What it is | Example | Comment |

| Simple | One noun phrase as the subject of a (finite) verb | Mary didn't believe him. | This is a finite clause which can stand alone |

| Compound | Two clauses (or more) of equal importance | Mary didn't believe him but John was adamant. | Both

parts of a compound sentence can stand alone so we can have: Mary didn't believe him. John was adamant. Usually, they are joined with something like and, or, but |

| Complex | Two clauses, one of which is subordinate (depends on) the other | Mary didn't believe him although he seemed very sure. | The second part of this is a subordinate clause: it cannot stand alone and retain the same meaning |

| Compound-complex | A combination of compound and complex sentences | Mary didn't believe him although he seemed very sure but I accepted what he said. | These sorts of sentences are sometimes difficult for learners to unpack and occur more in writing than speaking |

|

What do sentences do? |

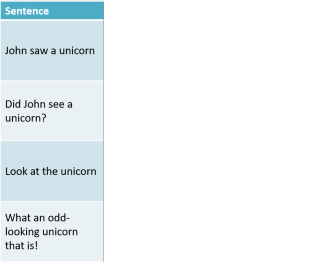

Sentences have four fundamental functions in language. Decide what the function of each sentence below is and then click on the table for an answer and some comments.

|

Unfortunately ... |

... there's another problem. The sentence type does not always

define its function. For more on this, see

the guide to form and

function (linked below) but if you have already done that, the following will be

straightforward.

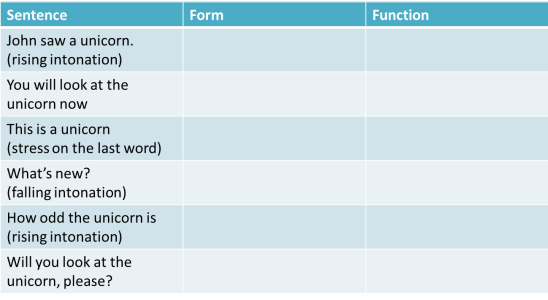

Can you complete the table again, stating what the form and function of

each sentence is? Click on it when you have an answer.

Generally, people expect the form to indicate the function so this sort of mismatch will cause problems for learners of the language. There are general rules, however.

- Any form of sentence can be interrogative with the right intonation. (Some languages, such as Greek, rely wholly on intonation and have no question form at all.)

- Offers are usually in the form of imperatives or questions (a

phenomenon common to many languages) so we can have, e.g.,

Would you like a drink?

or

Have a drink

etc. - Statements are frequently used as imperatives so we can have

You left the door open

meaning

Please close the door. - Interrogative forms can make positive or negative statements so

we can have

Do you ever listen?

meaning

You aren't listening

and

You're driving, are you?

meaning

You are obviously driving. - Tag questions such as

She's managing the office, isn't she?

can function as real questions when the intonation rises and as simple positive statements when it falls.

|

Statements; declarative sentences |

| I'm free at last |

Statements, sometimes referred to as declarative sentences can be recognised easily because the subject comes before the verb. These sentences state facts or opinions (and are not always true). They can be:

- Statements of the truth:

Water boils at lower temperatures at higher altitudes - Statements of opinion:

I may be able to come on Thursday - Requirements:

You must bring a pen and paper with you - Speculations:

She might have missed the bus - Wishes:

I hope the weather stays nice

and that is a short list.

Negative statements follow the same structure and are also declarative sentences. For example:

- Statements of the truth:

The temperature never falls below zero in this country - Statements of opinion:

I don't think she's coming now - Requirements:

You can't turn left at the end of the road - Speculations:

She might not have had time to talk to him - Wishes:

I hope she doesn't think I'm rude

|

Questions: interrogative sentences |

| Where were you that night? |

There are four ways sentences can be interrogative:

- By placing the auxiliary before the subject (called a

question inversion). For example:

Will you have time later?

Did she talk to her mother about it?

Has she seen it?

etc.

These questions usually require a simple yes/no/don't know answer and when they are used in classrooms, they are referred to as closed questions.

Sometimes such questions can be what is known as alternative questions such as:

Did she say she saw a unicorn or was I hearing things? - By using a wh- word (who, whom, where, when, what,

how, why) at the beginning of the sentence. Most of these

words need the auxiliary verb to come before the subject.

For example:

Why did she cry?

Where were they?

Who(m) did you call?

When can you come?

How did she do?

Why has she left?

What did she say?

etc.

but the words who and what can also be the subject of the question and not require the change in word order. For example:

Who told you that?

What broke? - By using a rising intonation on a statement form. For

example:

That's her mother?↑ I can't believe it! - By inserting what is called a question tag at the end,

separated by a comma, after a statement. For example:

That's where he lives, is it?

She was angry, wasn't she?

They don't live here now, do they?

The went out, didn't they?

She didn't show up, did she?

etc.

The usual form is that a positive statement is followed by a negative tag and a negative statement by a positive tag but there are many exceptions.

Forming question tags is quite tricky in English and there is a separate guide to this sort of question, linked below.

|

Commands: imperative sentences |

| Stand still! |

Commands are sometimes referred to as imperatives but, technically,

it is the verb which is in what is called the imperative mood.

Commands are exceptional in not usually have an obvious subject but

you is generally implied. They can be quite complex or

consist of only a single word. For example:

Talk to the boss about that if you aren't happy

Don't make her angry by arguing

Come early, please

Stop

Rarely, we can include the subject as in, for example:

You mind your own business!

but such sentences are quite assertive and cannot be softened with

please.

|

Exclamations: exclamatory sentences |

| What a silly thing to say! |

These are sentences which have an introductory wh-phrase

(what or how) but the word order which follows

is unchanged (unlike wh-questions). For example:

What a fool he is!

How silly of me to say that!

Understanding these sorts of sentences is not too challenging because many languages work in a similar way. However, forming them correctly is more difficult because:

- Exclamatory sentences with what are usually formed

with what + a noun phrase as in, e.g.:

What a beautiful sunset that is!

What interesting neighbours you have! - Exclamatory sentences with how are usually formed

with how + a complex adjective phrase which acts as the

subject of the sentence and the verb phrase is often non-finite

(usually an infinitive with to) as in, e.g.:

How thoughtful of him to write!

How daft of me to forget her name!

You will be forgiven for deciding not to focus on the form of exclamatory sentences in your teaching because they are somewhat rare and generally unnecessary. The other three sorts of sentences are, however, essential for anyone who wants to speak a language even at a very low level of competence.

| Related guides | |

| negatives and questions | for a more on these two areas |

| form and function | an essential guide to how form differs from function and vice versa |

| sentence grammar essentials | for a guide to how sentences can be broken down and understood |

| question tags | a separate guide to this form of question in English |

| basic course grammar section | for a straightforward guide to how sentences are formed |