Personal pronouns

The clue's in the name. Pro-nouns stand for nouns.

If you have done the guide to them, you'll know that nouns can be

proper (John, Paris etc.), common count (table, dog, house,

excuse

etc.), common mass (love, help, water, happiness etc.),

collective (jury, army, flock, management etc.) and plural (scissors,

contents, clothes etc.). Pronouns

can stand in for any of these sorts of nouns.

|

Person, gender and Case |

Before we can understand pronouns, we need to understand three main grammatical categories.

- person

this refers to who. There are three categories (in English):- First person

- Singular – I, me, my, myself etc.

- Plural – we, us, our, ourselves etc.

- Second person (English does not usually distinguish

between singular and plural –

most languages

do.)

- Singular – you, your, yourself etc.

- Plural – you, your, yourselves etc.

- Third person

- Singular – he, she, it, one, him, her, his, hers, its, herself, himself etc.

- Plural – they, them, their, themselves etc.

- First person

- gender

There are two definitions of gender in English:- a reference to the usual two sexes, male or female, with

regard to social and cultural phenomena as in, for example:

The company does not tolerate gender discrimination - a technical reference in the field of linguistics to a

grammatical category.

French, for example, has two genders which happen to be called masculine and feminine but German, along with a range of other languages has three, including neuter. The naming of genders by sex leads to all kinds of confusion but the term refers, in fact, to a class of nouns and has little to do with the cultural and social definition. There is no obvious reason why, for example, table should be seen as feminine and car as masculine. In German, for example, the term for a young girl is marked as neuter. Some languages have more than three classes of nouns and some have many more (up to 20, depending how you count and including concepts such as animate vs. inanimate, dangerous vs. harmless and so on).

Old English had three genders as does Modern German but there was a confusing and inconsistent use of gender even for nouns which were marked for sex. The Old English word fædernmæg, for example, referred to the paternal side of the family but was grammatically feminine.

In Modern English, gender is only shown in the pronoun system and there is no longer a distinction between, for example, the articles (a, an, the) used for nouns even when the gender is marked on the noun so we have, e.g.:

the duchess

the king

a brother-in-law

a lion

an actress

etc.

In the case of pronouns, however, English is also rather poor in only distinguishing gender in the singular third person.- he, she, it

- him, her, it

- his, her, its

- his, hers, its

- himself, herself, itself

- a reference to the usual two sexes, male or female, with

regard to social and cultural phenomena as in, for example:

- case

this refers to who is doing what to whom or what belongs to whom. There are four categories (but arguably only three in English):- Subject / nominative case –

I or

we refers to

the subject of the verb. For example, in

I smoke

the subject is I and in

John arrived

the subject is John.

In English the subject usually comes first. - Direct object / accusative case – this refers to the recipient of the

action. For example, in

I told John

I is the subject and John is the object and in

She drank the whiskey

She is the subject and the whiskey is the object. - Indirect object / dative case (in many

languages but in English this is also accusative) – refers to the recipient

of a direct object. A verb may have two

objects:

In

I gave the book to John

we have one direct object (the book) and one indirect object (John). In English we can reverse the order of the objects, dropping the preposition, to:

I gave John the book

Languages with case grammars will often distinguish between the two types of object by changing the form of the article or the noun (or both). English does not have a separate pronoun for indirect objects and for this reason, it is hardly worth taking the time to identify the dative case in English. But some languages do. - Possessive / genitive case

– refers to possession (among other things). For

example, in

I saw John's cat

the 's is referred as the 'genitive s' and in

That's my book

my is the genitive or possessive marker.

It is slightly loose to call this possessive in English because in phrases such as:

the leg of the table

the policy of the company

the people's vote

the father of the children

Mary's letter to me

and so on, the sense is not of possession but of origin, description or attachment.

- Subject / nominative case –

I or

we refers to

the subject of the verb. For example, in

Many languages you may speak or have studied make much ado about case

and the technical term for the changes to words that result from

it is called declension, but English is (relatively) simple in this respect.

Before we go on, if there's any doubt that you have understood this,

take a

test to make sure.

|

Personal pronounsThere are three main classes of personal pronouns |

|

Object and Subject |

|

I take a picture of her She takes a picture of me |

These are the most familiar and they look like this:

| subject | object | |||

| 1st person | singular | I | me | |

| plural | we | us | ||

| 2nd person | singular | you | ||

| plural | ||||

| 3rd person | singular | masculine | he | him |

| feminine | she | her | ||

| impersonal | it | |||

| *neuter | they | them | ||

| plural | they | them | ||

- As we will discover throughout, English lacks many pronouns

which exist in other languages:

- English has no polite and familiar forms of address for you. Compare French tu and vous, German du, Sie and ihr etc. In fact, English makes do with only one pronoun for both cases in the singular and the plural where other languages may have up to four forms.

- English uses it for both the subject and the object case.

- English only distinguishes gender in the third person singular. For the plurals, we don't. In this chart, it is referred to as neuter but, because English actually doesn't worry too much about gender for inanimate nouns (with rare exceptions), a better term is probably the impersonal pronoun. It is analysed here rather than in the section on impersonal pronouns simply because it shares structural characteristics with personal pronouns.

- Although English has both subject and object cases, it is, in fact, generally rather lax (some would say downright sloppy) in the use of the correct case form. Here's a short pedantry test. Which of the following would you consider 'correct'. Make a note and then click here for some comments.

| 1 | Who did it? Me. | Who did it? I. |

| 2 | I didn't know who did it but it turned out to be she. | I didn't know who did it but it turned out to be her. |

| 3 | Between you and I ... | Between you and me ... |

In 1, me is actually correct although it

refers to the subject case. If we ellipt (leave out) the verb

because it is understood, English uses the object pronoun for the

subject. So we get:

Who came?

Them.

Who sold it to you? Him.

etc. Put the verb

back in and we have to revert to the subject pronoun.

So we get:

Who came? They did.

Who

sold it to you? He did.

etc.

In 2, it is actually grammatically correct to use she and many would insist on it but

her and other object

pronouns are quite commonly heard in informal speech.

In 3, the correct form is me because all prepositions in

English are followed by the object case. This is an example of

people over-correcting because they imagine, wrongly, that I

sounds better. This phenomenon is called hyper-correction,

incidentally.

|

Possessive or genitive |

| It's mine |

There are also two sets of these:

| possessive determiner | pronoun |

| my | mine |

| our | ours |

| your | yours |

| his | |

| her | hers |

| its | |

| their | theirs |

Notes:

- The difference between the two columns:

In the first column, the words are determiners. They identify or limit nouns in some way just like words like the, some and that do. For example

I ate some bread

I ate her bread

I stole the money

I stole their money

and so on. The words in the first column are sometimes called possessive adjectives but that is rather an old-fashioned term. More accurately, and always on this site, they are possessive determiners.

In the second column, the words can stand as nouns (just like 'proper' pronouns). For example

My coat is here; hers isn't.

Their car is more useful than mine.

We can replace possessive pronouns by reverting to the noun with the possessive determiner so mine = my car, hers = her coat etc. These words are, therefore, referred to as possessive pronouns or nominal possessives. - The reason its only appears once is that it is not

possible to use it as a possessive pronoun. We can use it as a

possessive determiner in, e.g.:

What's wrong with the table? Its leg is loose.

but not as a possessive pronoun because that would give something like

*Which leg is loose? Its.

(It is marginally possible to use its as a possessive pronoun in a comment such as:

I hurt my leg and the dog hurt its

but many would never accept that.) - The possessive determiner its is frequently confused

with the contracted form of it is or it has (it's).

So we get, e.g.:

*Its important to ...

or

*It's leg is broken.

Please don't do this. The form with the apostrophe is always the contraction of is or has. - his is both a possessive determiner and a

possessive pronoun

It is his book

It is his

That can confuse lower-level learners. - English uses possessive determiners to refer to parts of the

body. Many languages will not have parallel structures for

something like

She cut her finger

preferring

She cut the finger

or even

*She cut herself the finger

We do, however, often use the article in passive sentences. For example,

I must have been dropped on the head as a baby

but even here the possessive determiner is possible.

|

Reflexive pronouns |

| Photographing themselves |

English uses reflexive pronouns but does not have an obsession

about them. The language does not, for example, insist that

some verbs are always reflexive as many languages do so we do not

usually say:

I washed myself

allowing

I washed

to be interpreted as reflexive when no object is identified.

| First person | singular | myself |

| plural | ourselves | |

| Second person | singular | yourself |

| plural | yourselves | |

| Third person | masculine | himself |

| feminine | herself | |

| non-personal | itself | |

| *neuter | themselves | |

| plural | themselves |

Notes:

- These are referred to as co-referentials (i.e., they refer to

the same thing) in some grammars.

We don't say, for example,

Sue wrote Sue a note

unless there are two Sues, but prefer

Sue wrote herself a note

When we use an object to refer to the same noun as the subject, in other words, English uses the reflexive pronoun. - English has few obligatorily reflexive verbs. We don't, for example,

meet ourselves (as we do in German), remember ourselves

(as we do in many languages) or (usually) wash ourselves.

However, we can make many transitive verbs reflexive if we want to:

I poured myself a drink

She drove herself home

etc. - This is the area where English actually does have a full set of pronouns, even to the extent of distinguishing between you plural and you singular (yourself vs. yourselves).

- You may hear or (perish the thought) be tempted to use theirselves instead of themselves. It's considered wrong in educated use. See the note on themself below.

|

Intensive pronouns |

Intensive pronouns have, in English, exactly the same form as

reflexive pronouns but they perform a different role.

For example, if we take a sentence such as:

The author congratulated

himself

then we can see that the author and himself refer

to the same person. That is to say that the object of the verb

is the same as the subject of the verb. That's what is meant,

of course, by the term reflexive.

However, in:

The author signed my copy

himself

then we can see that the subject of the verb is still the author

but the object of the verb is no longer the author, it

is my copy and the pronoun himself stands for

nothing at all in the sentence and just helps to emphasise that it

is important to the speaker. In other words, it intensifies

the expression.

The difference is that we can omit the pronoun altogether and still

retain the same meaning of the clause.

Here's another two examples to make the point clear:

- The President helped himself to lunch

- The President himself came to lunch

In sentence 1. we cannot omit the pronoun and arrive at:

*The President helped to lunch

because that makes no sense. The meaning of this sentence is

that the President served lunch to himself and was not waited on.

But, in sentence 2. we can omit the pronoun and arrive at:

The President came to lunch

without altering the meaning of the sentence, although we lose the

emphasis that the speaker wants to signal: i.e., that it is

important.

Above, we were careful to note that in English the reflexive and

intensive pronouns take the same form. That is not a language

universal and sometimes leads to some misunderstanding of what the

sentence really means.

For example:

- In German, the same effect is achieved with the pronoun

selbst which simply means something like self but

stands for all the intensive pronouns (myself, himself,

herself, ourselves etc.). Sentence 2. above then

translates in German as:

Der Präsident selbst kam zum Mittagessen

Scandinavian languages such as Danish do something quite similar as does Dutch. - In French, the effect is achieved by the use of the -même,

which means something like same, combined with the

pronoun. So, for example, sentence 2. above would

translate as:

Le président lui-même est venu déjeuner - Most Romance languages, such as Italian, Spanish and others

such as Greek and so on are referred to as pro-drop languages

which simply means that the subject pronoun is usually not

included in the sentence. So, for example, the translation

of he came in Italian is simply venne (not

lui venne).

To signal the importance of the pronoun, therefore, in a pro-drop language, it is enough to insert it but Italian and other Romance languages also have a word much like French and German (stesso, in the case of Italian) which can be inserted for emphasis.

Because the intensifying pronoun is often the focus of the

sentence, and often where the stress falls in spoken English, we

frequently move it to the end, after the object so, instead of:

I myself did the work

we usually prefer

I did the work myself

with the pronoun shifted to the end.

|

Reciprocal pronouns |

This is a small group consisting of just two multi-word pronouns.

- each other

- E.g., They really dislike each other

- one another

- E.g., They were all talking to one another about the play

The clue to the function of these two lies in the name: they are used when two or more nouns are doing the same thing and doing it reciprocally.

Generally, one another is slightly more formal and less

common. There are those who will insist that one another

may only be used to represent more than two nouns but that is not a

sustainable position although sentences such as

John and Mary

were talking to one another

sound odd to many people.

Using each other is a safe bet in all circumstances.

|

it, its and itself |

As we saw above, the pronoun it is usually analysed as a

personal pronoun because it shares the characteristics of the class (bar

the fact that there is no nominal use). More accurately, in terms

of meaning rather than structure, it should be described as an impersonal pronoun. Generally, as might be expected, the pronoun

stands for singular inanimate objects or 'lower' forms of life so we

have

Where's the wasp? It's behind you.

What's that? It's a new computer program.

and so on.

The pronoun has, however, some quirks in English, not always parallelled

in other languages.

- The pronoun can be used to refer to people:

- If the sex is unknown or unimportant:

That's her baby

Oh? What's its name

Is that child OK? It looks a bit sick. - With personal reference:

Who's speaking?

It's John

- If the sex is unknown or unimportant:

- The pronoun is frequently used for higher animals if the sex is unknown or unimportant. When the animal is, however, familiar to the speaker, the appropriately marked pronoun is preferred.

- It can refer to a previous text, written or spoken, in

the way the pronoun that can be used:

She failed her examination and that was a shock.

She failed her examination and it was a shock. - It can be a substitute for a prepositional phrase:

I put it in the cupboard. It was the obvious place - It can act as an empty or dummy subject when talking about the

time, the weather etc.:

It's snowing

It's almost seven - It can act as in anticipatory subject filling a similar role in

the sentence:

It is difficult to learn grammar

It is a shame that he can't come to the party

It is wrong to speak to her like that

This is a phenomenon also called a dummy or anticipatory it or, sometimes, the existential it.

In languages which have a neuter gender, such as German, Greek and

many Slavic languages, the neuter pronoun overrides the sex of the noun

so, for example, because the German word for the girl is a

diminutive and carries the neuter gender (as das Mädchen), the

correct use is, e.g.:

There is a girl outside and it is asking to talk

to you

Many languages do not deploy a dummy or anticipatory subject and that

can lead to inter-language error such as:

To speak Chinese is difficult

which is grammatical possible but unnatural.

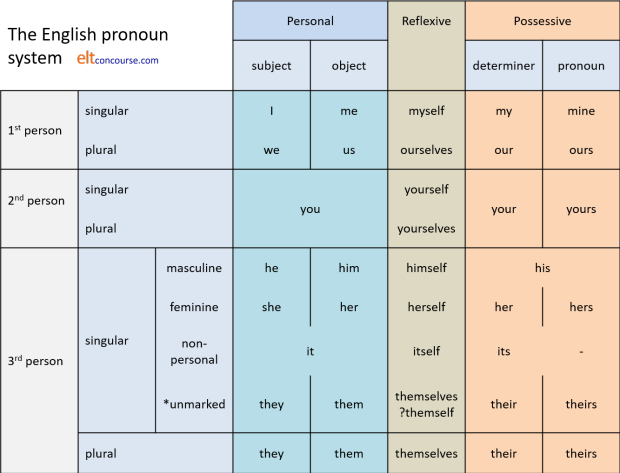

Here's a summary as a graphic so you can save or print it out easily.

Adapted from

Quirk, R & Greenbaum, S (1973:102)

with additions

*The singular unmarked row is a recent addition to reflect the increasing

use of the pronouns they, them, their, theirs to refer to a

singular individual unmarked for gender, avoiding his or her, he or

she etc. See below for a note on the pronoun themself.

ones and one's

Missing from the charts above is the impersonal, rather formal pronoun one. Here's how it works:

- As a subject pronoun, it is singular only and appears in clauses

such as

One must always remember that ... - There is no object pronoun form so we can't have

*He told one that ...

*Give it to one!

etc. It can, somewhat rarely, and quite formally, be used in the passive, however:

One has been told ...

etc. - The possessive determiner is one's as in One must always do one's best.

- There is no possessive pronoun form so we can't have, e.g.,

Whose is that?

*It's ones. - There is a rarely used reflexive pronoun, oneself, which occurs in, e.g., One must try to be true to oneself.

|

Personal pronouns and sexist language |

In olden times (i.e., before around 1990) it was considered acceptable for people to use he, him, his as what is called an unmarked pronoun form applicable to either female or male people. Times have changed and that is no longer the case so we have a number of results:

- The increasing use of plural forms for an unmarked pronoun.

Because English happens not to mark the gender of the referent in the plural, the pronouns they, them, theirs and the determiner theirs are frequently used to avoid the awkward his or her, he or she formulations. For example:

When a new student registers, they are given a test

Usually, it is a simple matter to avoid this in formal language by making the whole utterance plural and having:

When new students register they are given a test

and that conforms to the grammar of the language as well as the norms of a non-sexist culture.

(There are times when this use is almost unavoidable, however, as in, for example:

Whoever said that has got their facts wrong

If someone said they saw me they were mistaken.) - The occasional use in quite formal writing of alternate uses of he, she, his, hers and so on to balance the article or text. This can result in some clumsiness, especially when instigated in alternating paragraphs.

- An increased use of the conveniently unmarked pronoun one.

- An effort by a few people to invent a non-sexist pronoun

set. This is difficult because pronouns are what is known

as a closed-class set of words and introducing new ones into

such sets is a rare and troublesome process. It can happen

but it usually takes many years for a new item to be accepted.

For example, hizzer has been suggested as an

alternative to his or her and heesh as an

alternative to he or she.

In around 1990, a mathematician, Michael Spivak, used three personal pronouns which he sought to establish as unmarked forms. They are:

e for the subject pronouns he and she (pronounced /iː/)

em for the object pronouns him and her (pronounced /əm/ or /em/)

eir for the genitive pronouns and determiners his and her (pronounced /eə/ or /eər/)

To those three others have added:

eirs for the genitive pronouns hers and his (pronounced /eərz/ or /eəz/)

emself for the reflexive pronouns herself and himself (pronounced /əm.ˈself/ or /em.ˈself/)

This set of unmarked pronouns is usually referred to as the Spivak pronouns but has yet to become popular, leave alone conventional.

There are a number of other proposed systems for non-sec-marked pronouns and more on that can be accessed in the guide to gender in English, linked below. - The ad hoc invention of new pronouns as writers go

along. Here's one from the British Broadcasting

Corporation:

the tendency of managers to hire two or more subordinates to report to them so that neither is in direct competition with the manager themself

The pronoun themself does not actually exist in Modern English. It is an uneasy mix of the plural and singular and many users of English would disparage it. See the footnote.

BBC website, 2019 (emphasis added)

|

Non-binary uses |

There is increasing recognition that people do not universally

fall neatly into the categories of masculine and feminine and there

are many who claim to be non-binary and demand to be referred to as

they or them.

One cannot, of course, successfully set down rules for people to use

in this way but it should be noted that the use of the ostensibly

plural they to refer to a single individual unmarked for

gender has a long history going back at least 600 years.

The use of their to refer to a singular person is often

scorned by grammarians but, according to the Oxford English

Dictionary, is attested from at least 1300CE and appears in the

writings of, e.g., Fielding, Goldsmith, Sydney Smith, and Thackeray.

Merriam-Webster made they their word of the year in 2019 to

recognise the increasing use of it to refer to a single person

irrespective of sex.

The above has not covered all the pronouns in English because it is confined to personal pronouns. Words like, all, something, anything, everyone etc. are, or can also be, pronouns. For those, see the guide to impersonal and indefinite pronouns in the in-service section of the site, linked below.

| Related guides (most of these are in the in-service training section and more complicated) | |

| the word-class map | for links to guides to the other major word classes |

| pronouns: overview | for a very brief guide to the whole area |

| impersonal and indefinite pronouns | the guide to the other major class of pronouns |

| pronouns in English | go here for a list (new tab) |

| gender | a guide to how gender works in English and other languages |

| determiners | many pronouns can, in other environments, act as determiners |

| demonstratives | go here for a simple guide to demonstrative determiners and pronouns |

| cohesion | for more on how referencing holds language together |

| markedness | for more on how English marks things for case, gender, number and so on |

Reference:

BBC news website, 2019,

https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20191107-the-law-that-explains-why-you-cant-get-anything-done,

accessed 8/11/2019

Quirk, R & Greenbaum, S, 1973, A University Grammar of English,

Harlow: Longman

Footnote on

themself

There is no entry for themself in the current Oxford

English Dictionary online (https://www.oed.com). However, it

is noted that themself was the normal form of the third

person plural reflexive pronoun until about 1540. It had

disappeared by about 1570. Later, themselves became

the standard form. The form themself is labelled by

that source as rare, disputed or not widely accepted.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary (https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/themself)

notes that the rise of themself, if it occurs, will be

related to the increasingly common use of the singular they.

The editors did not judge that it was anything but rare in edited

and published materials.

The form may be re-emerging but an expression such as:

The manager may consider themself an expert

will still not be widely welcomed in formal writing.