Word class: the essentials

Because this is an overview of 10 word classes, it contains links as you go along to more focused guides for most word classes. Those links open in a new tab (except for those in the table at the end) so you can follow them and then close the page to come back to this one.

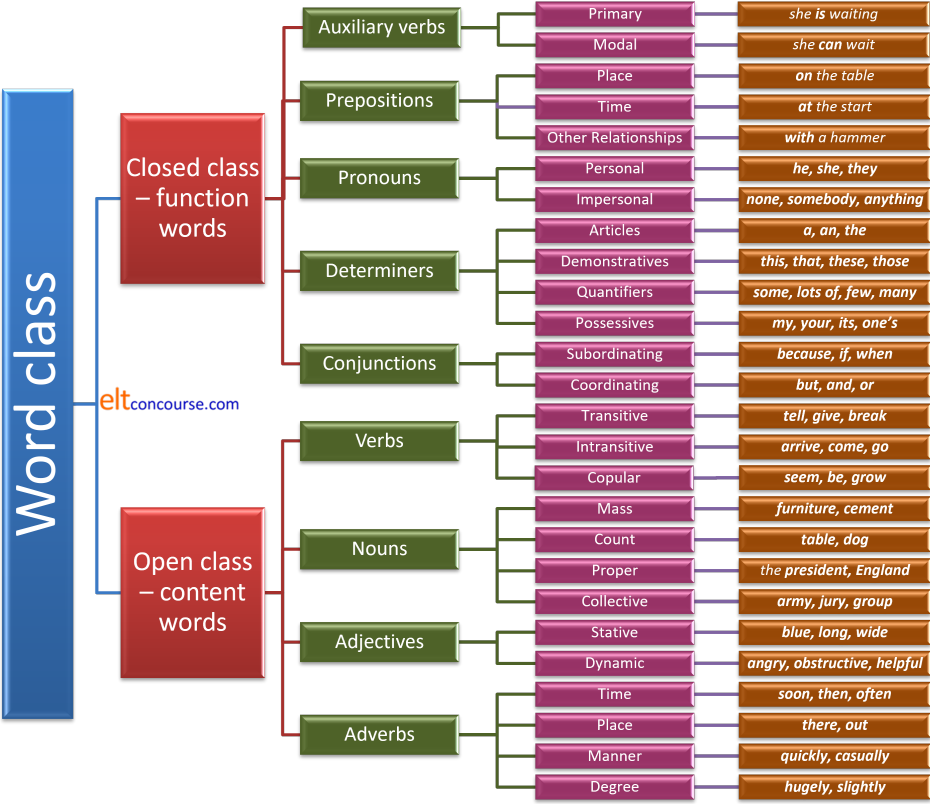

Generally, 10 classes of words are recognised in English. These

are sometimes called parts of speech.

Take a piece of paper and see how many you can remember from school

and then click here.

Now ask yourself why these are divided into two groups.

When you have an answer, click for the answer.

Group A words are called

open-class items because in theory we

can keep adding more to the list indefinitely. Languages

consistently create new nouns, for example, to describe new events or

objects.

Group B words are closed-class items. We do not usually create

new prepositions (although we can) and introducing a new pronoun into

the language is extremely rare (although people keep trying).

There are other classifications which we could use and popular one

is to divide words into member of two groups:

-

Major word classes:

- Lexical or main verbs (which are verbs which carry intrinsic meaning such as hear, encourage, avoid, jump etc.)

- Nouns

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

-

Minor word classes

- Auxiliary verbs, which carry no intrinsic meaning but function to express how the speakers feels about the main verb (must, can, should etc.) or operate to make tense forms (have in he has arrived, be in he is laughing etc.). The first group of these are called modal auxiliary verbs and the second group are primary auxiliary verbs and there are guides to all of them on this site.

- Pronouns

- Determiners (which includes articles and demonstratives in the first division above)

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

There is no simple way to divide the hundreds of thousands of words in the language as we shall see shortly.

One reason for separating word classes into these two

fundamental types is to allow us to think more clearly about

the language.

Closed-class, functional items are the concern of grammar but open

class items are the concern of lexis.

So, for example, choosing the correct item to go into a gaps

like this:

Mary gave John the video and

__________ was delighted with __________

is fundamentally a grammatical issue of selecting the

correct pronoun.

However, choosing the correct item to go in the gaps in

this:

Mary went into the __________ and

__________ the fridge to get some cold juice

is a matter of making appropriate lexical choices of the set

(technical term) of nouns or verbs which can fill the gaps

and make an acceptably comprehensible statement.

|

Determiners: the missing class |

There is, in fact, a word class missing from this list which is

used in more modern grammars: determiners.

Determiners are words which modify nouns (just as adjectives,

demonstratives and articles do). In older grammars,

determiners were often classed as adjectives (we can have few

dogs and fewer dogs) or as demonstratives (these

books, that man) or as articles (the car, some sugar)

or even as pronouns.

This is not satisfactory in many ways so the modern term for words

such as each, all, more, the, a, several, these, either etc. when

they come before nouns is simply

determiner.

There is an essential guide to determiners on this site linked in the list of related guides at the end but how determiners work in English is not a simple matter to analyse and is the subject of a separate (and more difficult) in-service guide. Following the second guide successfully will be quite difficult if the area is new to you. You will almost certainly need to understand issues of (un)countability in nouns before tackling it.

|

|

Mini-test Now click for a test to see if you can identify what these different word classes actually do in the language. Don't worry if you don't get it all right. It's explained below. |

|

Overlapping word classes |

It is a mistake to assume that we can look at a word and, from its appearance

or meaning, consign it to one of the 10 or 11 word

classes we have identified. That's not how it works.

In fact, we consign words to classes by their positions in sentences

and their grammatical function. Meaning comes a distant third.

This is what is meant:

- Some words are only members of one word class. So, for example, ceiling is a noun and nothing else, decide is a verb only, between is a preposition and so on.

- Many thousands of words can be members of two or more word

classes, however, depending on what they are doing in a sentence

so, for example, in:

Please clean the car

the word clean is operating as a verb but in:

The car is clean already

the word is operating as an adjective. - Some words have characteristics of more than one word class

so, for example:

that is a demonstrative determiner which has a plural form like nouns (those)

little is a determiner (and sometimes a pronoun) which has comparative and superlative forms (less and least) which makes it work like an adjective.

Another example is that in

He is running

the word running is clearly a verb but in

Running is good exercise

the word is operating as a noun but still looks like a verb (and retains its verbal meaning).

And so on. Do not be tempted to jump to conclusions and

suggest to learners that a word is always assigned to one of the

main classes. Context is vital.

The phenomenon we see here is called gradience or categorical

indeterminacy which simply means that we accept that word-class

boundaries are sometimes fuzzy.

|

Three ways to judge word class |

How we assign words to classes can be managed by considering three factors, the last of which is the most powerful and accurate. They are:

- We can look at the meaning of words so we get rules such as:

- Words which describe things or people are adjectives

- Words which refer to objects and people are nouns

- Words which refer to actions are verbs

- Words which say where, when, how often or how an action is done are adverbs

This works OK when the words in question are well behaved but, unfortunately breaks down when we encounter words such as:

- politeness which is descriptive rather than referring to an object or a person but is not an adjective

- misfortune which is a noun but doesn't refer to an object or a person

- exertion which refers to an action but is not a verb

- frequency which refers to how often something happens but is not an adverb

- We can look at the form of words so we get rules

such as:

- Words which end in -ly are adverbs

- Words which take a plural form with -s or -es are nouns

- Words which take -d or -ed to show a past tense are verbs

- Words which can be altered to show degree by ending in -er or -est are adjectives

Again, this works well for many thousands of well-behaved words but breaks down when we consider:

- put which is a verb that doesn't change at all to show tense

- sheep is a noun which does not take a plural ending at all (but can be plural)

- information is a noun but it has no plural

- likely is an adjective which ends in -ly

- often is an adverb that doesn't end in -ly

- absent is an adjective which has no endings for degrees

- We can look at the grammatical function of a word

and see where it occurs in the structure of the language (its

distribution is the technical term). This does give us

workable rules because we can suggest:

- Nouns fill the gap in

The __________ broke the window - Verbs fill the gap in

She __________ the parcel - Adjectives fill the gap in

She was very __________ to see her mother - Adverbs fill the gap in

They __________ came to my house

- Nouns fill the gap in

There are other tests we can apply to decide on word class but in what follows, we will be using a combination of all three, depending mostly on the last one.

|

Key characteristics of word classes |

|

Nouns |

Apart from obvious (and slightly inaccurate) distinctions between abstract

nouns (beauty, hope etc.),

concrete nouns (apple, table etc.) and proper nouns (James, Canada etc.), there is a key distinction

learners (and you) need to understand:

countability

and uncountability.

(There is a dedicated guide in this part of the site to mass and count

nouns linked in the list of related guides at the end.)

- Countable nouns can be preceded by a number (two cats),

a or an

(a dog) and a few (a few letters). They usually take plural endings.

In the plural, we use a plural form of the verb with them (are

not is, for example).

So we get, e.g.:

Two people have arrived and the woman is his sister - Uncountable nouns are better referred to as mass nouns and

cannot be preceded by a number or a few (but can be preceded by

some and a little) and only take plurals in unusual meanings when we make

them countable. We use the singular form of the verb with these.

The bare form of mass nouns can stand alone so we allow:

Milk is nourishing

but not

*Cigarette is bad for you

|

Task On a piece of paper (or in your head if you have the memory for it), divide these into the two groups: mass or count: sugar, pea, furniture, happiness, sheep, army, money, attention, pliers, coffee, teacher, food, door, discomfort, information, luggage, suitcase, chair and then click here for some comments. |

It's not as easy as it looks, is it? There are two important things to understand.

- Some words (such as sugar and door) are clear cases of

uncountable and countable examples. Others are more complicated

because we can use them in both ways with different meanings.

Compare

You have my attention (mass)

with

His attentions are unwelcome (countable).

Some nouns, such as sheep are countable but take no plural. Some obviously countable things, such as money, are treated as mass nouns in English.

Virtually all mass nouns can be made countable in English when we are using them to classify things. For example

There are some coffees which are too bitter for me

They have lots of German wines on the list etc.

We also use mass nouns casually as if they were countable as in, for example:

I'll get the coffees

which is just a short way of saying

I'll get the cups of coffee - Different languages deal with these things differently.

In German, for example, information is a countable

noun. In Greek, so is money. When introducing a

noun, remember that students will probably presume it's

countable unless you make it clear otherwise.

So you'll get people saying furnitures and it'll be your fault, not theirs!

Nouns are quite a complicated area of the language and there is

an essential guide

to nouns linked at the end and also a more complicated and detailed

in-service guide to nouns on this site.

|

Verbs |

Verbs in English, and many other languages, come in three distinct flavours. This is what they are:

- Lexical or main verbs

MOVE!

These are what most people think of when they are asked to give an example of a verb.

The verbs in this class carry their own meaning and can often stand alone and still make sense so, for example, we can understand what is meant if someone says:

Go

Speak

Read

Explain

Drink

and so on.

They also have a meaning which can be defined quite easily when they occur in phrases and longer units of language as in, e.g.:

She left

We spoke to them

She altered it

I drank the beer

and so on.

This is an open class of words so we can invent new verbs for actions and states which we want to decribe. Hence we get, for example:

Text me with the date

Google it

Upload the data

and so on. - Copular or linking verbs

LOOKING GOOD

These verbs also carry some kind of meaning but cannot be understood when they are used in isolation so, for example, while we can happily understand:

She grew angry

They got lost

We were in London

That appears correct

and so on, we cannot understand:

She grew

They got

We were

That appears

because we do not know what the subject of the verb is being linked to. Without that information, the statements make no sense. - Auxiliary verbs

EMPTY

These verbs carry no meaning at all because they are members of a closed class of functional words and their role in the language is grammatical. They cannot stand alone and mean anything to most people unless another main verb is understood.

All the highlighted verbs in the following examples are auxiliary verbs of some sort:

We were given the money

She has sent the letter

I had been told about it

She can't sing

I must go soon

They got their house repaired

We daren't ask

That should help a bit

You may be able to see from that list that there are two main sorts of auxiliary verbs:- Primary auxiliary verbs

These function to form tenses and other structures in the language and on this site, we recognise four:- have

which makes what are called perfect tenses such as in:

She has finished

They hadn't arrived in time

I will have sold it by then

and also makes what are called causative structures as in:

She had the work done

I had my pocket picked

They had the house swept

and so on. - be

which makes progressive tense forms such as in

She is working tonight

They are spending a week in France

She is always thinking of you

and also operates in English to make what are called passive sentences as in:

I was told

Mary isn't being invited

She will be sacked

and so on. - do

which is used in English to make questions and negative forms (and sometimes to emphasise a lexical or main verb) as in, e.g.:

Do you like this wine?

Did she see him?

Didn't he call?

I don't understand

We didn't go

I do enjoy it

etc. - get

which is not always considered a primary auxiliary verb but functions as one, like have, to make a causative as in, e.g.:

I got the house painted

She got him to paint the garage

etc.

and can also be used to make what is called a dynamic passive clause as in, e.g.:

The house got damaged in the storm

They got allowed into the club

- have

- Modal auxiliary verbs

These do not (with one exception) make tense forms or other grammatical structures. What these verbs do is to make the speaker / writer's stance clear. For example:

I can arrange that (expressing ability or willingness)

You should go home (expressing obligation)

I might help (expressing possibility)

It must break under that pressure (expressing a general truth)

(The exception is the verb will and its past tense, would. This verb can express the speaker's point of view as in, for example:

She will do it if you ask (expressing her willingness)

I would come earlier if it helped (expressing my willingness)

but it can also function as a primary auxiliary verb to make a future form as in:

I will be 40 tomorrow

She will have told her

The next train to arrive at platform 3 will be the 4:10 for London Paddington

They would have arranged it earlier.)

- Primary auxiliary verbs

All these forms of verbs have their own essential guides on this site and the following guides will open in new tabs:

lexical or main verbs | copular verbs| primary auxiliary verbs | modal auxiliary verbs

If you want to learn much more, try the in-service verbs index.

There is another key distinction which concerns lexical or main

verbs only.

Can you divide

this list into three groups? Think about how you use the

words in a sentence.

smoke, give, go, enjoy, breathe, beat, come, arrive, listen, see, hear, feel, say, speak, think, carry, jump, reciprocate

Click here when you've done that.

| Used with an object | Used without an object | Used both ways |

| give enjoy beat feel say carry |

go come arrive listen think reciprocate |

smoke breathe see hear speak jump |

The issue here is called

transitivity. Transitive verbs take an object,

intransitive verbs don't but some verbs can do both.

We can say

I smoke

with no object so intransitive, and

I smoked a cigarette

with the object so transitive.

We can say

She carried the box

transitive

but not

She

carried.

because carry is always transitive.

We can say

I arrived

He went

She came

but not

*I arrived / went / came the airport.

because arrive, go and come are all intransitive verbs.

Sometimes, there's a change in meaning:

He can hear

and

He can hear it

are different meanings of the verb.

When you teach a new verb, bear in mind that languages deal

with transitivity differently. In some languages, for

example, you can say

I jumped the table

meaning

onto, not over, or

She

listened the music.

Set verbs in a context and

make sure that your learners are aware of whether they are

transitive, intransitive or both.

There is an essential guide to lexical or main verbs, linked above.

|

Conjunctions |

Here's another list to categorise. Conjunctions can

coordinate two clauses or they can

subordinate one clause to another

(making one clause depend on the other).

For example:

He makes the beds and he does the washing up

is an example of

and working as a coordinating

conjunction. Both parts of the sentence are meaningful without the

other.

I won't make the beds unless you do the washing up

is an

example of unless acting as a subordinating

conjunction. We can't understand the second clause without

reference to the first.

Here's the list to categorise.

but, after, although, as, and, as soon as, because, before, if, in order that, so, unless, until, when

Click here for the answer.

| Coordinating | Subordinating |

| but so and |

after although as as soon as because before if in order that so unless until when |

Notice that so appears in both columns. It can be

coordinating, as in

He is a farmer, so is his brother

and

subordinating as in:

I did the washing up so you can make the beds.

There are many more subordinating conjunctions and they carry a range of

meanings: conditionality (if, unless), consequence (so),

reason (because), time (when, until) etc.

Once a learner is able to use coordinating conjunctions, it's time to

teach subordination.

There is a third type of conjunction

you need to know about: correlating (or correlative) conjunctions.

Here's the list:

both ... and, just as ...so, (n)either ... (n)or, whether ... or,

not only ... but (also)

Can you make an example using these? This class of

conjunctions is confined pretty much to linking ideas inside sentences

rather than linking sentences together. Click

here for some

examples of them in use.

Both John and Mary are coming

Neither Fred nor I can open it

Either you do it now or you can wait until I have time

I don't know whether they are coming separately or together

The problem is not only important but (also) urgent

There is an essential guide to conjunctions linked at the end and from there you can go on to a more advanced guide to conjunctions on this site. Both guides also deal with correlating conjunctions (the third sort).

|

Prepositions |

This a notoriously difficult area of English because there's seems

little rhyme or reason to which preposition we use where. The

other issue, as usual, is that languages differ. Some languages

don't use prepositions at all, preferring postpositions, so we

get The bridge along.

But there are some rules.

- Distinguish between movement and position:

- I went to the station (direction of movement)

- I arrived at the station (position)

- Distinguish between exact place and general place:

- He is in the station at the booking office

- He is in London at the station

- Distinguish between exact time and approximate time in the same

way:

- He came at 6 o'clock in the morning

- The earthquake happened at 4 in the afternoon, on a Monday in March

- Distinguish between prepositions which describe absolute

position and those which describe things from the speaker's point of

view:

- The house is between two trees / the house is next to / near the cinema / the house is opposite the church (wherever you are standing)

- The house is behind the trees / the house is in front of the garage (from where you are standing)

There is an essential guide to prepositions on this site linked at the end.

|

Adjectives |

There is, of course, a separate essential guide

to adjectives linked at the end so this will be brief.

Adjectives in English modify nouns (usually) to distinguish them in

some way and (usually) come in

one of two places:

- Before the noun they describe (attributive use):

- a fat cat

a huge house

etc. - After the noun they describe and linked to it by a verb such as be, look like, taste, smell, appear etc. (predicative use):

- The cat is fat

The house appeared huge

etc.

|

Articles |

Articles are a sub-class of determiners. We said above that

we would explain why we are usually concerned with only nine word

classes and it is because articles used to be considered a separate

class but are now included as a subset of determiners. They

have, however, some important characteristics and are usually

treated as a separate target for teaching purposes.

Again, there's

a guide to the

essentials of articles linked at the end and from there you can

access a

more advanced guide to articles on the site.

There are only three true articles in English: a, an and

the. The other choice in English is no article at all

and that is usually represented by a zero sign, like this: Ø.

The zero article is important because it is used in English to refer

to all instances of something.

(Some analyses will include some in the

list but it's actually not an article although it can work in a very

similar fashion.)

A few examples are all that's needed here:

a house,

a university,

an apple etc. (The

choice of a or an is determined by the sound

at the beginning of the following word,

not the spelling.)

the house,

the man I met etc.

Ø people often complain,

Ø cars pollute,

Ø smoking is bad for you,

Ø water is a scarce resource etc.

The rules for deciding which article to use are not easy so go to the guide to articles for more detail. Essentially, the rule is:

Decide what you are talking about. There are only three choices:

- One of many – indefinite specific reference (a house, a person, an idiot etc.)

- All of them, everywhere – generic reference (Ø people, Ø tigers, Ø computers etc.)

- This one exactly – definite specific reference (the woman on the corner, the train for Ø London, the visitors to the park, the tourist industry etc.)

|

Adverbs |

Adverbs are words which modify just as adjectives modify

nouns.

In English, adverbs do three things:

- They modify verbs (hence the name):

I walked slowly

She went outside

They enjoyed the play immensely - They modify adjectives:

She is extremely rich

They were deeply unhappy

That's an unnecessarily rude thing to do - They modify other adverbs:

He drove extremely carefully

She came very late

They talked quite amicably

In many languages they are not distinguished from

adjectives but English is not like that.

There is an

essential guide to adverbs on this site linked below so a few examples of

what is meant will do here:

He walked slowly and

carefully to the door

(answering how?)

He's is coming soon

(answering when?)

He sometimes tells tall stories

(answering how often?)

They wandered around

(answering where?)

She mostly enjoyed the

party (answering to what extent?)

etc.

|

Pronouns |

Pronouns are a sub-class of what are called pro-forms and stand

for nouns or ideas.

There are guides to pronouns on this site accessible from

the initial plus

words index.

Pronouns usually stand in for or replace nouns so instead of saying:

The

rain fell and the rain was heavy

we can say:

The rain fell

and it was heavy.

And, instead of:

When I read the book, I realised how good the book was

we can say:

When I read

it, I realised how good the book was

In the first example, the pronoun refers back to the noun (rain)

and in the second it refers forward to the noun (book).

Sometimes, pronouns can stand for whole clauses or even longer

pieces of language as in, for example:

Getting the report written up and delivered to the right

people on time was difficult but she managed

it

in which the pronoun it stands for the whole of Getting

the report written up and delivered to the right people on time.

Essentially, there are two sorts:

- Personal pronouns. For example:

- Mary didn't have a pen so I

gave her mine

(instead of

Mary didn't have a pen so this person gave Mary the pen belonging to this person) - Other pronouns. For example:

- Somebody is at the door

(instead of An unknown person is at the door)

Nothing is too much trouble

(instead of No action is too much trouble)

He wanted money so I gave him some

(instead of The male person wanted money so this person gave the male person some money)

|

Demonstratives |

Demonstratives are a sub-class of determiners.

There are four of these in English (this, that, these, those),

although some other expressions work rather similarly,

and they refer to what we want to talk about. In other words,

they demonstrate or point out what we are referring

to. There are two decisions to make:

- Is it near or far?

- Use this or these for things near to you:

I want this one

I can give you these tickets

Use that or those for things further away:

Can I have that one?

Take those tickets over there - Is it singular, mass or plural?

- Use this and that for singular or

mass nouns:

Give him that wine

I didn't ask for this meal

Use these and those for plural nouns:

Can I take these glasses?

I haven't opened those bottles yet

Demonstratives can also act as pronouns:

I don't want these apples

(demonstrative), I want those

(pronoun).

Demonstrative determiners are considered in the essential guide to determiners, linked below.

|

Interjections |

This is the simplest class of all. These words are not, in

a sense, 'real' words because they represent noises things and

people make. For example:

"Ouch!" he cried.

"Aaargh!

I've done it again."

"Pssst."

he said.

The car went 'clunkety-clunk' and

stopped

|

Words and phrases |

In this guide, for the sake of simplicity, we have been focusing

on individual words to identify the classes into which they fall.

However, all word classes can sometimes be represented by phrases

so, for example, in:

Dogs are often faithful

we have four single words acting as representatives of word classes

(nouns, verbs, adverbs and adjectives respectively).

However, in:

Peter's old dog has been almost always

faithful and loving

we have phrases forming representatives of phrase classes but

their grammatical functions are parallel. The phrases are:

noun: Peter's old dog

verb: has been

adverb: almost always

adjective: faithful and loving

Here are some more examples of phrases acting in the same ways as single word classes:

- nouns

- car : William's old Volvo

house : corner house with a blue door - verbs

- went : must have been going

have : can't have had - conjunctions

- so : in order to

but : either ... or - prepositions

- on : in front of

by : at the back of - adjectives

- black : old, green French

sunny : cold and wet - adverbs

- usually : now and then

carefully : slowly and thoughtfully - determiners

- my: all the

the : half the many - pronouns

- her : each other

us : one another

There is nothing particularly mystifying about this but it is worth bearing in mind that when we talk of word class, we really mean word or phrase class.

Summary

The following is a basic summary which leaves out rather too much

but covers the essentials of word classes.

You can click on the green areas of your choice to go to the

essential guide to the individual word classes.

You can get it as a PDF document by clicking

here.

|

An important distinction |

This distinction is one which confuses people new to the analysis of English (and sometimes, alas, people who should know better).

- Word class

is to do with an item's syntactical function but that does mean that it is the same as grammatical function.

For example, we know that in something like:

Put the old __________ on the table

we can fill the gap only with a noun or a noun phrase to get something like:

Put the old grammar books on the table

We know too that the phrase grammar books is a noun phrase and that this is how we talk about its class. - Grammatical function

is to do with how the items fit together in a sentence or clause. In the example above, the phrase grammar books is the object of the verb put.

Other word class items can also perform the grammatical function of the object of a verb and they are highlighted in black in these examples:

I think in the corner is a good place

I want to go

She told me

We can also make a noun or noun phrase the subject of a verb and that is the grammatical function of the highlighted items in:

Fred went home

The grass grew too long

The people in the corner have not ordered yet

and so on.

But other word-class items can also function grammatically as subjects so we may also find:

To visit would be wonderful

Under the stairs is the best place

We left early

and so on.

Grammatical function refers to what the item is doing in relation to the rest of the sentence but that is different from an item's word or phrase class.

The three grammatical functions are usually confined to:- subjects: The old lady gave her the money

- indirect objects: The old lady gave her the money

- direct objects: The old lady gave her the money

(The situation regarding grammatical function is actually a bit more complicated than this, but, providing you are clear about the difference between word class and grammatical function, that's enough.)

Click for a test of the key elements of word class.

| Click on the green sections

of the diagram above for the guides to individual word classes. Other related guides are: |

|

| the word-class map | this link takes you to the index of guides to word classes on this site including ones in the in-service area |

| initial plus words and vocabulary index | from here you can track down other guides related to words and meaning |

| in-service lexis index | for more advanced and technical guides to various areas of lexis |

| word and phrase class | for a more advanced guide to the area which assumes knowledge of this guide |

| articles: essentials | for the initial plus guide to the area |

| (un)countability | for a guide which focuses on this area |