Understanding reading

The best way to improve your knowledge of a foreign language is

to go and live among its speakers. The next best way is to read

extensively in it.

Nuttall (1996:128)

If this is true, then one of the greatest benefits we can give our students is the confidence and willingness to read extensively in English. There are more reasons for this.

|

What the research shows |

- Frequent readers have better vocabulary

- Frequent readers use grammar more accurately

- Frequent readers have positive feeling about the language

- Frequent readers show higher motivation

- Frequent readers have better listening, speaking and writing skills

It can, of course, be argued that the causation may work both ways. Frequent readers may read frequently because they have better vocabularies and find it easier, are more motivated in any case and so on.

|

Reading: the mechanics |

For many of us, reading seems such a commonplace skill that we

overlook how complex and difficult it is to learn. A much-cited

figure is that it takes around 600 hours of instruction to learn to read

with any fluency and some people never truly master the art even in

their first language. We should not, therefore, treat the area

lightly or assume that our learners will simply transfer the skill from

first to subsequent languages.

Being able quickly to read a text and grasp the meaning and

organisation requires a reading speed of around 200 words per minute and

a native speaker of English will usually achieve something around 300

words per minute (Nuttall, 1982: 36). Speeds below 200 words per

minute will usually result in non-comprehension because each word is

being processed too slowly for the overall meaning to be gathered.

For speakers of languages which do not have an alphabetic writing system

or use a different alphabet, attaining those sorts of speeds is a

challenge.

This is especially true for people whose first languages use logographic

or syllabic writing systems and even those which have an alphabetic

(i.e., more or less phonemic) system may use a range of alphabets as

well as writing right to left or top to bottom.

For more, see the guide to

spelling in English.

To get a flavour of what it is like to decode an unfamiliar text, try

this:

![]()

and that is in English. It's even more difficult in a language you

are just beginning to master.

|

Eye movements and word recognition |

When we read, we do not move our eyes smoothly along a line of text but focus roughly speaking about one third of the way along each word for a matter of about 200 milliseconds. We do this because, so the theory goes, it allows us to focus both on the shape of a word and on its initial two letters which carry so much of the information. We can view 3 or 4 characters to the left of our main focus and around 6 spaces to the right. This allows us simultaneously to decode the current word and begin processing the next word. If the next word is short enough, we can jump over it completely and focus on what follows. Then, in something like 30 milliseconds, our eyes jump to the next word. Thus, we work our way along the text in very small and very rapid jumps. The technical term for this fast movement between fixation points is, incidentally, saccade.

As we fixate on each word, we need, of course, to recognise it very

quickly. Native speakers can do this almost instantly with very

well known words but are slower when it comes to unusual items. We

also tend, quite often, to backtrack and re-read function words which

allow us to get the connections between phrases. So, for example,

in reading a sentence such as:

Give me a lift and I'll buy you a pint

we may return to re-read the coordinator and to figure out that

it is, in fact, acting as a conditional subordinator in this sentence,

not as an additive coordinator which is its usual role. (The

sentence could be rephrased as If you give me a lift, I'll buy you a

pint.)

It has been suggested that having an active schema (or set of conceptual associations) allows native speakers to skip large sections of text because we can predict what comes next. However, research (reported in Schmitt, 200: 47) shows that, in fact, most of the text is focused on and processed in the way described here.

|

Types of text. What do we read? |

Here's a list of possible text types that anyone might read in a day or so.

| newspaper article | a novel | this web page |

| bus timetable | TV schedule | recipe |

| restaurant bill | maintenance instructions | news website |

Now think about how we read these things. Do we, for example, read every word? Do we move logically through the text, line by line? Do we read very carefully or just glance about? When you have an answer, click for some comments.

- When we are dealing with some texts, for example, a recipe or a set of maintenance instructions, it's important that we understand nearly everything. If the book says twist anti-clockwise or do not allow it to boil, it's important that we get it right.

- With other texts, we can be a bit more careless. Typically, on a news website, people will run their eyes across the links looking for a story that interests them and then access the text for a more detailed look at the information. Even when we are quite interested in a story, we still often won't read every word, preferring to skip to the important (for us) bits of the story.

- Other texts, such a bus timetable require different approaches. We can't usually just read from top to bottom, left to right because we don't want the information from most of the text. We only want to know when the next bus goes to where we want to be, usually. If you are looking for a name in a telephone directory, don't start at page one and read till you find it.

- Depending on how much we are engaged, reading a novel requires a different approach, too. We will usually read with some care and even back-track to re-read sections but we can ignore parts of the text and simply follow the story. If we are getting a bit bored, we may even start to glance through the text to find out what happened in the story.

- If we are trying to learn something or prepare for an examination, we will often read and re-read with some care, making sure we understand the text. Is that how you are reading this?

It's clear, then, that we deploy different skills depending on:

- the sorts of text we are accessing

- our reasons for reading

|

Types of reading. How do we read? |

- Scanning

- This is the bus timetable kind of reading. We scan the text looking for key data such as Destination, Time, Bus number etc. It's also how we might find a telephone number or scan an encyclopaedia entry to locate a specific bit of information such as numbers or lists of events.

- Skimming

- This is how we might approach a TV schedule if we don't know what we want to watch. We run our eyes quickly across the text to get a general idea of what each programme is about. Once we find something that interests us, we read it for detail and find out when it's on and where. We are interested in the gist, not the detail at this stage.

- Intensive reading

- We deploy this skill when we are concerned to understand as much as we can. Maintenance instructions, recipes, study texts and so on are the typical things we read like this. Often we will read things more than once and we will usually try to understand every word of the text. We almost always use this approach with short texts containing key information.

- Extensive reading

- We read extensively when we are reading for pleasure and also when we are hoping to get some general information. In this mode, we usually don't read extremely carefully and we can ignore words we don't know. We may backtrack sometimes if we get lost but usually we simply read through the text, following the writer's organisation. Novels, magazines, newspaper articles etc. are all accessed like this.

To see if you have understood what you have read so far, try

this short test.

|

Bottom-up and top-down processing |

You will encounter these terms both in the discussion of listening and reading because they are applicable to both.

- Bottom-up processing

- involves the learners using knowledge of the meaning and pronunciation of words, knowledge of the grammar of the language and how texts fit together to understand the meaning of what they read.

- Top-down processing

- involves learners using their knowledge of the world and the type of text they are reading to (its usual organisation and the topics) to fill in gaps with intelligent guesswork and prediction.

It is important to understand that neither of these processes occur in isolation. Good readers continuously deploy both bottom-up processes to understand structure, meaning and nuance and top-down processes to understand the purpose of a text, its intended audience and its writer's communicative intentions.

There is a clear implication here:

We need to make sure that we use a range of texts and

procedures to ensure that our students get adequate practice in all the

reading approaches.

|

The knowledge |

From here on the discussion of reading skills becomes slightly more technical. If you are reading this guide because you are taking or have just taken an initial training programme, you probably do not need much more than we have already covered. However, if you are going on to further training or are simply interested in learning more, read on.

Before going on to thinking about how to teach reading skills,

it is worth pausing to consider what knowledge learners need to

bring to the process of understanding what they read. In other

words, we need to look for some kind of syllabus for reading

skills which goes a little beyond simple descriptions of top-down

and bottom-up processing, important though they probably are.

Reading is not a passive process.

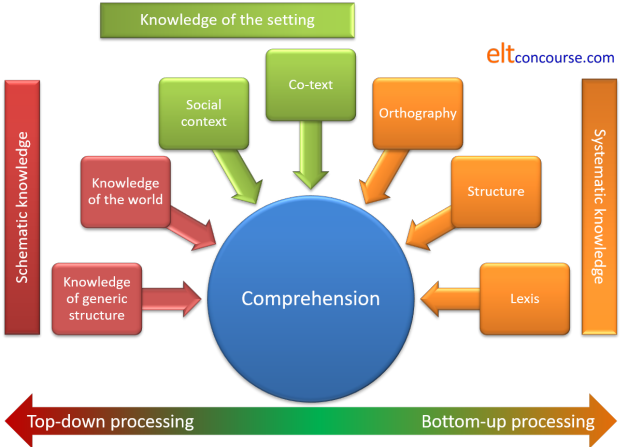

Here's a diagram with some notes. The diagram is divided by

colour into three parts.

Think a little about the meanings and implications for teaching in each of the areas on the diagram and then read on for some notes.

- Schematic knowledge is sometimes referred to as part of

top-down knowledge although that is an inaccurate or at best a

partial way to understand the area.

- Knowledge of generic structure involves a number of

issues which are covered in more detail in the guides to

genre (linked below). Briefly, however, we need to

consider:

- text staging: genres have culturally conventional

stages for information to occur. Written texts, in

particular tend to fall into a number of recognisable

genres which have their own peculiarities and culturally

determined ways to present information.

For example, a narrative (such as an short story or an email telling a tale) will begin with orientation which will provide information about the who, the when and the where of the story. The second stage will usually involve the identification of a complication or problem, the third stage will relate how the problem is solved or what resolution is found to the complication and the final stage (the coda) will usually concern the writer's personal response to the story.

Recounts, such as news reports follow a slightly different format but orientation will usually come first setting out what happened, where and when followed by a record (usually in chronological order) of events. Towards the end of the text there will often be some reorientation and (especially in newspapers) some direct evaluation of the events from witnesses and others affected by whatever has occurred.

A procedural text, for example, will have a very different structure because it is designed for a different cultural purpose (to explain how something is done) and this will usually start with the goal of the process (why you are doing it) and then go on to tell you about the materials and resources you will need before setting out, step-by-step, how the process is managed. A recipe is a good example and so are texts explaining software or hardware connections and so on.

Knowing how these sorts of texts, whether written or spoken, are structured in terms of where the information comes is very helpful to readers because they will be alert to spot each stage separately rather than being faced with a mass of data. - elements of the language: all genres will use

language elements of different sorts to help them

fulfil their cultural purposes.

Taking the example of a news report recount, such a text will conventionally contain circumstances of time and location (in the centre of the city, off the coast of Dover, in the early hours of the morning, during the rush hour etc.). Conventionally, too, the orientation phase of the text will concern itself with events having present relevance to the reader and this will, in the course of things, often involve the use of relational tense forms such as Two men have been arrested, the police have sealed off the area, ambulances have now left the scene and so on. The rest of the text, recounting events will usually be pinned to past time markers, yesterday, at four o'clock etc., and use simpler tense forms. There is a guide, linked below, to tense and genre.

The text will normally revolve around what are called behavioural or material process verbs such as do, go, become, collapse, sink, swim and so on.

Finally, in the evaluation section of the text, we may well find projecting verbs such as neighbours reported, a police spokesman asked for, the Prime Minister accused etc.

If the reader is primed to focus on decoding circumstances and verbs of this sort, comprehending a text becomes a good deal easier.

- text staging: genres have culturally conventional

stages for information to occur. Written texts, in

particular tend to fall into a number of recognisable

genres which have their own peculiarities and culturally

determined ways to present information.

- Knowledge of the world goes beyond the text. We

rarely come to a text knowing nothing of its content or

topic in advance. We know, for example, that the

little booklet that comes with a new router is unlikely to

contain a recount or narrative or a text discussing safe use

of the internet. In fact, of course, we will expect it

to contain a procedural text telling us the goal and the

materials and the steps to take to achieve the goal

(connection). One reason a lot of us struggle with

such texts is that they are often translated from languages

with different cultural conventions for text staging.

Equally, of course, we know what newspapers are for and what forms of text they usually include (and these vary from straight news reports of events (recounts), through expositions in the opinion and letter pages, discussions in the financial and political sections and procedural advice in other life-style pages). Newspapers are a rich source of reading material and it is certainly motivating for learners to be faced with something locally relevant and interesting but we need to take a bit of care to focus on one text type at a time.

Visual clues are also very helpful and one reason why newspapers tend to head reports and other text types with eye-catching graphics or images.

If the learners' knowledge of the world concerning the topic of the text is activated early on in the process, it becomes a good deal easier for people to understand what they read.

- Knowledge of generic structure involves a number of

issues which are covered in more detail in the guides to

genre (linked below). Briefly, however, we need to

consider:

- Knowledge of the setting also comes in two distinct parts,

one requiring top-down processing and one requiring more formal

bottom-up knowledge.

- The social context is critical, of course because our

knowledge of it allows us to predict the purposes for which

someone is writing. The assumption we all start from

is that people write to communicate something and knowing

the writers' intentions helps very

considerably with understanding what they write.

What we are discussing here is the tenor of a text which is revealed through the types of language that the writer uses. A text designed to convince us of the truth of an argument, for example, will often contain extensive use of modality referring to duties and obligations whereas one which is designed to persuade the reader that it is a logically argued discussion will be much less dependent on strong modality and rely more on hedging and expressions of modest conclusions. Recount texts will contain almost no modality at all because they are concerned with facts and events, not feelings about truth and advisability. Procedural texts will contain a good deal of sequencing data (often using numbered points and so on) and stories will concern themselves with the mental processes of the characters.

The social context includes, too, an understanding of what the writer feels about the audience. If we know, for example, that someone is writing to colleagues in the same profession, we will expect certain amounts of shared knowledge to be assumed but a writer recounting events in a foreign country will be at some pains to set the scene and explain the local context. Local newspaper reports will be less concerned with such matters, of course.

The social setting will very often give us that information before a word is spoken. - In addition to contextual clues, more sophisticated

readers also rely on co-text data. For example,

knowing that, in a discussion text, Con the other hand prefaces

a counter argument and nevertheless precedes a

reinforcing point is helpful information.

Knowing, too, about other discourse features and being alerted to their importance is also helpful. Here, the functions of conjunctions, pronoun referencing and so on will play a part. For example, relative clause structures are a feature of many written text types and being able to unpack what follows pronouns such as who, which, that as well as adverbs such as where, why and so on in their post-modifying roles is critical to understanding the content of what one is reading.

- The social context is critical, of course because our

knowledge of it allows us to predict the purposes for which

someone is writing. The assumption we all start from

is that people write to communicate something and knowing

the writers' intentions helps very

considerably with understanding what they write.

- Finally, we come to the purely bottom-up processing skills

on the right of the diagram and these all focus on understanding

the formal nature of the language.

- Orthographic knowledge is the place to start, naturally, because reading in an unfamiliar script or in a language which uses very different punctuation conventions is often troublesome and may block understanding altogether. English is often and sometimes unfairly criticised for having a loose relationship between spelling and pronunciation so it is sometimes the case that a learner will simply not recognise a word, such as thorough or disputed, in its written form which has previously only been encountered in speech.

- Structural knowledge is important because, for example,

it allows us to set events in time by focusing on tense and

aspect, to see how writers' intentions vary through the

modality they use and to understand that tense forms are

intended to set a state, action or event in absolute time or

to connect it relatively to other times. The

difference between

The victims were taken to hospital

and

The victims have been taken to hospital

is not random.

This structural knowledge is often underestimated by those who feel that top-down processing is the new normal. - Lexis or semantic knowledge is, naturally, vital for reading comprehension. Some unknown words my be safely ignored (especially if, for example, a word is identifiable by its co-text as an adjective or adverb) but too many unknown items will effectively block comprehension. Hence the need to train readers in the art of ignoring some words and inferring the meanings of others from co-text.

That's quite a lot, isn't it, so reading skills cannot be approached in a haphazard manner. All these areas of knowledge need to be in place and they all need to work together to make reading comprehension function at all.

| Related guides | |

| skills teaching | this is an overview of what you and your learners need to know when developing or practising skills |

| teaching reading | for the essentials-only guide to how we can develop our learners' reading skills |

| teaching reading | for the in-service guide to the area which is more detailed |

| genre | this is the in-service guide to genre which covers the most important aspects of identifying the characteristics of a range of genres |

| tense and genre | for the guide to how certain tense types conventionally occur in certain text types |

| pages for learners | click through to reading exercises or reading lessons. You can incorporate the materials into your own lessons |

| inferencing | for some help with how we figure meaning from context and co-text |

| synonymy | for more words with similar meanings and the perils of assuming they are the same |

| teaching vocabulary | for the in-service guide to teaching meaning |

| context | for a guide to the essentials of context and co-text |

When you are happy that you have understood this page, click here to

go

on to some teaching ideas.

Or click here to go to

the guide to

assessing reading skills.

Reference:

Nuttall, C, 1996, Teaching reading skills in a foreign language,

Oxford: Heinemann English Language Teaching

Schmitt, N, 2000, Vocabulary in Language Teaching, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Other references you may find helpful

include:

Alderson, J. C, 2000, Assessing Reading, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Bamford, J & Day, RR (Eds.), 2004, Extensive Reading Activities

for Teaching Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Grellet, F, 1981, Developing Reading Skills, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Hudson, T, 2007, Teaching Second Language Reading, Oxford:

Oxford University Press

Sanderson, P, 1999, Using Newspapers in the Classroom,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Urquhart, AH & Weir, CJ, 1998, Reading in a Second Language:

Process, Product, and Practice, Harlow: Longman

Wallace, C, 1992, Reading, Oxford: Oxford University Press