Syllabus design (and a bit about coursebooks)

Three questions to start us off:

What is your definition of a syllabus?

How does it differ from a curriculum?

How does it differ from a course plan?

Click here when you have three answers.

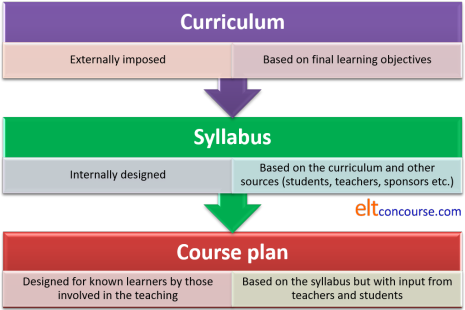

Actually, the questions are quite difficult to answer. They shouldn't be but ELT authorities and practitioners use the terms rather differently. Some would say loosely. For the purposes of what follows, the definitions used in this guide are:

- syllabus

- a list of the topics to be covered on a course. This is usually drawn up by the institution in which teaching takes place sometimes with input from both internal sources (students, teachers, academic managers etc.) and external sources (sponsors, examination boards, ministries etc.).

- curriculum

- an externally imposed and prescribed set of learning objectives and content. Such lists are often drawn up by ministries or other external powers such as examination boards.

- course plan

- a list of the content and ordering of a schedule of work to be covered by a group of learners and their teacher(s). Such lists are usually drawn up by teachers and/or academic managers and based on a syllabus which, in turn, may be based on a curriculum.

Diagrammatically, we can represent the distinction as a hierarchy:

Curriculums (or curricula if you prefer)

do not usually prescribe how a course will be taught; they merely

list what is to be taught and what the learners should be able to do

by the end of a course (or series of courses spread over

considerable time such as secondary school curricula).

Syllabuses (or syllabi if you prefer) often do prescribe the methodology even if only

implicitly (see below).

Course plans are usually set out for a period of days, weeks or

months and are more an overview of the timetable into which day and

lesson plans can be inserted. They are often quite explicit

concerning the design of a lesson in terms of methodology.

|

Types of syllabuses in English Language Teaching |

There are rather too many of these.

The following is available as a slightly shorter PDF document.

The design of a

syllabus often betrays the underlying theory of language and learning to

which the

syllabus writers adhere.

For example, if a syllabus lists only structural items to

be taught, it shows that the writers believe that language is

structurally based and that learning requires the ability to use

structures, grammar and other formal linguistic items successfully.

Nunan (1988:52) points out, in a centrally important text in this area

the traditional distinction between syllabus design and methodology has become blurred

This is because more recently devised syllabus types clearly

require the application of certain types of methodology to deliver

the content. A task-based syllabus, for example, demands the

application of a task-based teaching approach.

Later, Nunan (1991:284) has summed up the point thus:

Traditionally, syllabus design is concerned with the selection and grading of content, while methodology is concerned with the selection and sequencing of tasks, exercises, and related classroom activities. Metaphorically speaking, syllabus design is concerned with the destination, while methodology is concerned with the route. With the development of task-based approaches to language learning and teaching, this distinction has become difficult to sustain.

Here's a list of syllabus types:

| Syllabus | Description | Typical content |

| Structural | A 'traditional' syllabus, listing formal language items to be learned. The ordering of items usually depends on a judgement concerning their complexity rather than communicative utility. Simple forms are handled first, more complex ones later. | Such a syllabus will usually contain

lists of grammar, structures, lexis and phonological features to be covered.

For example, First conditional Gerunds after verbs going to for intentions/plans have got (possession) Imperatives let's + bare infinitive. Past simple vs. Past progressive Present perfect with for, since etc. Words to describe the appearance of people Schwa and other common weak forms |

| Skills-based | This

kind of syllabus targets language abilities rather than the

formal aspects of language. This is sometimes called a process syllabus and is often combined with (or mistaken for) a procedural or topic-based syllabus. |

Usually a list of skills to be demonstrated and taught.

For example, Delivering a short talk Writing a letter of complaint Understanding a lecture Reading an academic article Maintaining and giving up turns Backchannelling |

| Situational | This kind of syllabus will cover the settings in which learners will have to deploy appropriate language. A key distinction is made in such syllabuses between structural and lexical words (by, be, which etc. vs. house, table, gasp etc.) |

Typical content will include items such as: At the doctor's In the post office Travelling by air, train, car Renting a flat |

| Topic-based | This

is a syllabus organised around topic rather than language

structure which has similarities to both a lexical and a

situational syllabus (with both of which it is often combined). These sorts of syllabuses are often designed with a specific group (or age group) in mind or when teaching English for Special Purposes. |

Typical topics in such a syllabus might include: Lifestyles Personal relationships School Technology Religion The weather Negotiating a contract TV quiz games Global heating |

| Lexical | This kind of syllabus focuses on lexical patterns and common ways to express meaning. It usually draws on corpus research to discover patterns and frequencies in the language. |

Typical items would include: Collocational patterns: adjective + noun, adverb + verb etc. Delexicalised verb patterns with make and do by: expressing who, how, when, where would: expressing past habit, unlikelihood |

| Notional | A syllabus which focuses on learning the language to describe universal concepts, notions such as size, temperature, frequency, likelihood etc. |

Typical content will cover lists such as: adequacy/inadequacy desirability/undesirability texture delay/earliness frequency speed |

| Functional / Communicative | A

syllabus which focuses on learning the language to perform

certain functions in the language such as asking for and giving

information, apologising etc. Such a syllabus may subsume within it a notional approach but that is not common. It is common to find it combined with a Situational Syllabus, however. |

Typical content will cover lists such as: Asking about/expressing likes and dislikes Greetings and introductions Offering/accepting/declining refreshment Expressing forgetfulness Expression political opinion Granting forgiveness Service encounters and politeness routines Asking for/offering help |

| Task-based / Procedural | This

kind of syllabus focuses on using tasks to help learners deploy

language communicatively. It is important that the tasks

represent real-world language. This kind of syllabus is often combined with a skills-based or process syllabus. |

Task

types are usually listed and sometimes particularly tasks are

prescribed. For example, Negotiation tasks: reaching a consensus Forward planning tasks: planning an excursion Judgement tasks: writing a review of a film Prioritisation tasks There is a guide to task-based approaches on this site linked in the list of related guides at the end. |

| Learner-generated | This relies on learners knowing what they need to do in English and what they need to learn to master the skills they need. The syllabus is then negotiated between the students and the teacher/institution. |

Typically, these syllabuses end up as lists of concepts, topics,

skills and structures such as: Using the present perfect Writing an email Interacting informally Giving a presentation at work |

| Mixed | This is possible the most common type of syllabus and focuses on combining elements of all syllabus types so that each lesson or series of lessons focuses on different aspects of what is to be learnt. |

Typical content will include items from any of the areas above. In many cases, a mixed syllabus will be a combination of a structural, functional and topic syllabus. Language will be set in a topic area, the structure will be presented and practised and then the learners will focus on using the language to communicate. Many coursebooks prescribe this type of syllabus for reasons explained below. |

This is not, as you would imagine, the end of the story. There are other components of syllabuses which, while not forming a syllabus in themselves, are often inserted into the syllabus. Two of most common ones are

- cultural syllabuses

which list the sorts of things learners need to know about the speech community's shared values and knowledge (for example, systems of government, cultural icons etc.). This kind of syllabus often forms a considerable part of the programme for teaching, for example, immigrant populations. It is often, for obvious reasons, combined with Situational and Topic-based syllabuses. - content syllabuses

in which the language to be taught is drawn from the need to teach and learn a different topic – teaching English through the teaching of other knowledge and skills such as happens in English-medium schools situated in many settings where English is not the official language, for example, teaching sciences in English because the majority of relevant texts are in that language.

Another term for this kind of syllabus is Content and Language Integrated Learning or CLIL, to which there is a guide on this site linked from the list of related guides at the end.

|

Combining syllabuses |

It is rare to find any course or institution focusing on only one of the syllabus types outlined above. Most will combine aspects of two or three syllabuses to try to meet the needs and preferences of learners who may be quite disparate in this regard. For example:

- communicative plus

- Communicative Language Teaching varies.

A strong form of the approach is one in which any formal teaching of structure (including phonology) is abjured, the principle being that learners will acquire the formal aspects of language in the effort they make to communicate in the language.

A weak form, which is more commonly used, sets as its target the enhancement of the learners' ability to use language for real communicative purposes. However that is achieved is a matter for the teacher and syllabus designer (often the same thing).

It is common, therefore, to find a communicative syllabus alongside a structural one with elements of a task- and skills-based syllabus running parallel with additional elements of a situational syllabus and, sometimes, a cultural aspect.

This can be effective in terms of, particularly, the teachers' comfort zones and the learners' expectations of what a language course should involve.

The downside is that the various strands may not be adequately linked so the linguistic resources in terms of structure and phonology required by the learners to attain their communicative goals may not be given adequate attention. This often means that, while the learners are deploying language to achieve some form of quasi-realistic communication, they are not actually learning anything new. Lessons can, in this way, focus only on practice rather than be real learning opportunities. - structural plus

- The other side of the equation is the combination of a syllabus

which is ostensibly structural in nature and takes language items

and the grammar and phonology in order of complexity will have,

grafted onto it, communicative tasks for the learners to carry out

and in which to set the formal aspects they are learning.

This can be effective in showing the learners the real-life relevance of the language they learn as they proceed through the items on the syllabus.

The downside is that in order to achieve the mix, the communicative tasks which are carried out have no relevance to the learners' needs outside the classroom and, while an exercise to use the present perfect simple, for example, to discuss current levels of experience may be a vehicle for the deployment of the structure, its relevance in terms of whether the learners will ever need to do that in the language is overlooked. - task-based plus

- The temptation, when using a task-based approach to teaching, is

to combine the syllabus with elements of a skills-based approach and

even some elements of a structural approach. This is often

done to try to ensure that the learners have the skills and language

they need to carry out the tasks they are set. It is also the

case that elements of a communicative syllabus are implanted in the

syllabus to make the tasks more focused on real life.

The advantage here is that this may overcome the common criticism of task-based approaches that they do not, in fact, lead to learning but to learners deploying language and skills they already know.

The disadvantage is that the principle underlying task-based learning is overlooked, i.e., that the tasks are meaningful to the learners. Task design then tends to be driven by assumed skills, structural or communicative needs rather than the tasks representing real language use for the learners. - situational plus

- Situational syllabuses attempt to set language socially rather

than treat it as a series of items to learn (whether those are

structural, notional or functional). The obvious temptation is

to use the situation as a backdrop for the use of communicative

strategies or the deployment of structural, phonological and lexical

items, rather than focusing on the social nature of a situation.

The positive outcome is that communication is based on recognisable and often familiar settings for the learners who can see the relevance of what they are doing to real-life encounters.

The negative impact is that the social nature of language may be overlooked so the learners use language which is appropriate for the people in the room with whom they are interacting but are not prepared for encounters (whether spoken or written) in which the power relationships, intentions and social distances may be very different. - topic plus

- Topic-based syllabuses are rarely used discretely but

topic-driven courses are quite common. In such a course, for

example, the learners may be exposed to language set in a variety of

topic areas such as education, health, transport

and so on.

This sort of syllabus can readily be combined with situational, communicative, skills-based and lexical syllabuses and the last of these is often a frequent partner.

The advantage is that lexis, in particular, is encountered in a connected field with the nouns, verbs, adjectives and so on most typically encountered together. This makes the teaching of collocation (both lexical and textual) much easier and more consistent.

The disadvantage is that, in an attempt to insert other elements into the topics, realism is overlooked and communicative functions may be inappropriately deployed with learners talking, reading, listening and writing about topics which may, or may not, be relevant or of interest to all (or any) of the learners in a group.

It is particularly perilous to prescribe topics in a syllabus for groups who are not known at the times of the design.

All the syllabus types outlined in the table above can be combined

with others in this way to try to provide some kind of all-round

approach which will engage and be of use to the learners. That's a

positive.

The negative is that this kind of eclecticism can lead to a loss of

focus and the inappropriate insertion of rogue elements into a syllabus.

|

Who determines the syllabus? |

Unless the syllabus is purely learner determined, somebody, somewhere

needs to decide on the targets of a teaching programme. This is

often neither the people who will deliver it nor those on the receiving

end of the teaching-learning process. That is, some say,

unfortunate.

We noted above that curriculums are often decided nationally or

regionally and even in the private sector, may well be determined by

powers somewhat distant from the classroom such as sponsors, agents and

head office managers. Curriculum designers are, into the bargain,

often not concerned with the nitty-gritty of classroom content but

with setting targets in terms of competencies that the learners will

attain by the end of the process. In the UK, for example, the

language studies curriculum is set out by the government and has the

following aims:

The national curriculum for languages aims to ensure that all pupils:

- understand and respond to spoken and written language from a variety of authentic sources

- speak with increasing confidence, fluency and spontaneity, finding ways of communicating what they want to say, including through discussion and asking questions, and continually improving the accuracy of their pronunciation and intonation

- can write at varying length, for different purposes and audiences, using the variety of grammatical structures that they have learnt

- discover and develop an appreciation of a range of writing in the language studied

Source:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-languages-progammes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-languages-progammes-of-study

At what is called Key Stage 3, the government further demands (op cit.) that:

Teaching should focus on developing the breadth and depth of pupils’ competence in listening, speaking, reading and writing, based on a sound foundation of core grammar and vocabulary.

So, the requirement is for a mixed skills- and structure-based

syllabus in schools.

And that requires:

Grammar and vocabulary

- identify and use tenses or other structures which convey the present, past, and future as appropriate to the language being studied

- use and manipulate a variety of key grammatical structures and patterns, including voices and moods, as appropriate

- develop and use a wide-ranging and deepening vocabulary that goes beyond their immediate needs and interests, allowing them to give and justify opinions and take part in discussion about wider issues

- use accurate grammar, spelling and punctuation

Linguistic competence

- listen to a variety of forms of spoken language to obtain information and respond appropriately

- transcribe words and short sentences that they hear with increasing accuracy

- initiate and develop conversations, coping with unfamiliar language and unexpected responses, making use of important social conventions such as formal modes of address

- express and develop ideas clearly and with increasing accuracy, both orally and in writing

- speak coherently and confidently, with increasingly accurate pronunciation and intonation

- read and show comprehension of original and adapted materials from a range of different sources, understanding the purpose, important ideas and details, and provide an accurate English translation of short, suitable material

- read literary texts in the language [such as stories, songs, poems and letters] to stimulate ideas, develop creative expression and expand understanding of the language and culture

- write prose using an increasingly wide range of grammar and vocabulary, write creatively to express their own ideas and opinions, and translate short written text accurately into the foreign language

which strongly implies some kind of communicative syllabus running alongside skills and structure development with an element of a cultural syllabus added to the mix.

What the government is silent about, however, is precisely how the syllabus itself is to be written, what it will contain and how it will be delivered. For that, teachers and schools are obliged to develop their own syllabus or use an off-the-shelf set of teaching materials which provide the syllabus for them.

In non-state sector education, it is rare to find a curriculum set out in such detail but even in small establishments some effort is usually made to list the aims of a programme and the competencies to be attained.

|

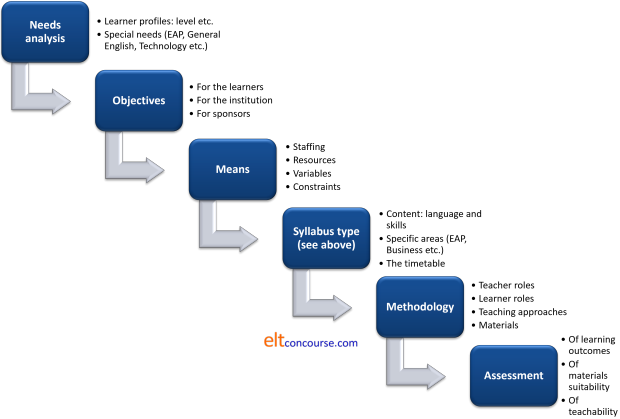

The elements of syllabus design |

Near the end of this guide, you will find a diagrammatic representation of how a syllabus

may be designed in terms of exploiting published materials but, before

we look at that, it is as well to consider how the process of syllabus

design works, whoever is in charge of it.

The following is based, somewhat loosely, on the methodology of

designing a syllabus for a course in Academic English (Jordan, 1997:57)

but the considerations are identical, whatever kind of syllabus you are

involved in devising.

A little explanation:

- The first two steps are linked:

- First, we need to establish the needs of the learners and for

that, see the guide to needs analyses, linked below in the list of related guides.

We need here to bear in mind what the students want, what they

actually need, what any sponsors want and what demands will be

placed on the learners when they have completed the course and start

to use the language.

The list of needs at this stage has to be prioritised because not all will be core needs. A simple way to do this is to divide the needs into two categories:- essential: core needs

- desirable: peripheral needs

- From that, we can identify the goals of the course and there

will usually be a list of these concerning communicative competence,

linguistic accuracy and the skills we are aiming to teach, develop

or improve. This will not be a short list on most courses.

The goals of the course at this stage will be in the form of a wish list because the outcomes of the next step will probably reduce them to what is realistic.

- First, we need to establish the needs of the learners and for

that, see the guide to needs analyses, linked below in the list of related guides.

We need here to bear in mind what the students want, what they

actually need, what any sponsors want and what demands will be

placed on the learners when they have completed the course and start

to use the language.

- The third step involves careful and clear-sighted considerations of what is possible given the staffing, the institute's resource base and constraints concerning time availability and so on. When this step is complete, it may be necessary to re-visit the objectives bearing in mind the constraints that have been identified.

- The fourth step involves a hard look at the possible syllabus types we might use (or a mix of them, in all probability). From this will emerge a timetable which is balanced in terms of how the needs (steps one and two) have been prioritised.

- Next comes considerations of how the syllabus will be delivered

and that involves looking at three elements:

- Approach: what principles of language analysis and language learning theories are we applying?

- Design: how are lessons to be constructed? This will usually involve considering Presentation → Practice → Production vs. Test → Teach → Test or Task-based structures for lessons. It will also involve some consideration of how autonomous the learners can be and how much of the syllabus may be delivered in non-classroom-based environments (learning centres, on-line work, private study etc.). This may well have emerged from the first step of the process where we set out the learner profile.

- Techniques and Procedures: Once we have a general idea of how

most of the lessons will be structured, we can consider the nuts and

bolts of the approach(es) we have selected. Types of tasks,

amounts of individual, group and pair work, teacher roles and so on

as well as the choice of materials (see below) will all be set out

here.

In other words, what will we expect to see happening in the classroom and elsewhere?

- Finally, no syllabus is complete without planning some way to

evaluate its outcomes. We need to assess:

- How well the learners mastered the course content: this involves summative testing at specific points but certainly at the end of the course and, often, some formative testing along the way to see what needs recycling or re-presenting. Often there is an element of self-assessment by the learners included in this process.

- How well the syllabus worked in terms of load on the teaching staff and stresses it induced in the institution. On large courses, some kind of questionnaire for the teachers needs devising but on smaller undertakings a focus group with a clear agenda is probably all that is required.

- How motivating, enjoyable and useful the learners found the course. There is a range of ways to do this and they are often combined – questionnaires, focus groups, one-to-one interviews etc.

As you can see, designing an entire syllabus from scratch is a

demanding and time-consuming process.

Few teachers have the time or the skills to set about writing their

own syllabus from scratch, although course and lesson planning are

expected to be two of their competencies. For this reason, schools

often opt for a coursebook (or books) which in their view will

successfully provide a syllabus which matches the aims of their

programme(s).

|

The syllabus and coursebooks |

Sheldon (1988:237) pointed out that:

ELT coursebook publishing is a multi-million pound industry, yet the whole business of product assessment is haphazard and under-researched.

Coursebook production is a complex, expensive and time-consuming

business (unlike, for example, the cobbling together of a set of

engaging classroom activities into a kind of busy teacher's source

book).

The undertaking requires (or should require) researching the demands of

an international range of curriculum authorities, the setting out of a syllabus, the construction

of the students' book, the teacher's book, a set of audio / video

materials, a website and, often, a test book and set of supplementary

materials. All this material has to be written, edited, re-written

and assembled by a team of dedicated, professional and qualified people

working under an experienced and well-paid editor.

In addition, professional graphics designers and other in- and

out-of-house experts are drawn into the process which may take several

years to complete.

Moreover, all of this work has to be repeated because the course may

consist of a complete set of materials at four or five levels.

It is little surprise that this is not task lightly undertaken.

Publishing houses are not, for the most part, charitable organisations and they want to maximise the financial returns on their considerable investment in the process of creating, marketing, printing and distribution. To do this, they have before them an enormous and potentially hugely lucrative market. The British Council's states it this way:

By 2020, we forecast that two billion people will

be using [English] – or learning to use it.

The British Council, 2013

A market of over a billion people (and rising) is not something at which many publishers are reluctant to aim. A yearly income of €0.05 per learner would yield €50 million.

Accordingly, the focus is on producing materials with the widest possible appeal to the broadest market they can access worldwide. There are significant implications:

- Breadth of content:

An example is given above of what is required from a language-teaching process in UK school and most governments worldwide have developed similar schemes. Unfortunately for course-book authors and their publishers, all the schemes are different, some radically so.

There is little incentive for publishers or writers to confine the market for their efforts too narrowly and, therefore, deny themselves the opportunity to sell their materials worldwide. Consequently, a coursebook or a series of them will endeavour to cover the whole of the content of very disparate curriculums and will include targets, language items and skills which will appeal wherever the materials are used and fit well with whatever form of syllabus is developed locally.

This will be evident, especially, in the structural work covered in course materials so that each part of the series covers the core curriculum of as many state-driven syllabuses as possible. Materials which do not do this run the risk of being locked out of some nations' educational institutions. - Cultural neutrality:

Similarly, publishers and authors will naturally be constrained not to offend or to make their materials too culture bound. Topics and situations which, for example, may appeal to European audiences may have less relevance elsewhere and those which are attractive and familiar in some cultures may be mysterious or offensive in others. - Social neutrality:

By the same token, coursebook producers will attempt not to limit their potential market with materials which appeal to particular age groups, sexes, occupational categories or social classes. - Methodological neutrality / coverage:

There is little point, for publishers at least, in producing materials closely linked to any specific approach or methodology so, for example, content which is only suitable for use in a strictly communicative setting will be abjured and the materials must cater for structural, task-based and lexical approaches, among others.

Hence the tendency for course materials to include a range of activity types and procedures aimed at different approaches to defining best practice and theories about how second-language acquisition is best promoted in the classroom. - Aim neutrality / coverage:

Coursebook writers do not, by definition, know the people individually at whom the materials are aimed. General coursebooks are, therefore, written with general, not to say diffuse, aims in mind because the pressure is to produce materials which have learning outcomes applicable to the widest possible set of needs for using English. Skills work will, accordingly, be evenly balanced usually and the genres of texts used will not be explicitly linked to any particular register. - Learner appeal:

Although learners are infrequently consulted by institutions concerning the content of their course materials and the nature of the syllabus they are obliged to follow, institutions will be concerned to choose material which they feel will be engaging and trusted by their customers and clients. Learners and many teachers often see the coursebook as the syllabus and will be impressed, so the theory goes, by a contents list which is long and broadly based, covering skills, structures, topics and settings of general appeal to the 'middle ground'. - Teacher appeal:

In many institutions, the teaching staff will have limited but real choices concerning the materials they use to deliver the syllabus (which they may have contributed to designing). Hence, authors and publishers are concerned to produce materials which can be used by teachers at all levels of training and expertise. Materials which require high levels of skill in classroom management or language and skills analysis will be avoided in favour of simple-to-use materials which do not require large amounts of preparation. - Formulaic procedures and activities

The way the materials are presented will also follow a consistent pattern with each unit in each part of the course looking very much like all the others apart from the content. Even across a series of coursebooks aimed at different levels of learner, the same phenomenon is apparent with each part of the course mirroring its counterparts at other levels. This makes it easy for even novice or under-skilled teachers to use the materials because, once they are familiar with the formats, the teaching approach follows predictable patterns.

Overall, it may be argued that the combination of these factors will

mean that commercially produced coursebooks will often be bland,

scattershot, predictable, unrealistic, irrelevant and intellectually,

culturally, socially and emotionally

undemanding.

In a word, boring.

In another word, ineffective.

|

The DIY syllabus |

The disparagement of coursebooks in place of a proper syllabus above

may tempt some to abandon the idea of an externally imposed syllabus

altogether and opt for a wholly teacher- (and learner-) generated syllabus directed

towards the needs of the individuals in the group while maintaining

relevance to any imposed curriculum aims.

That might be a mistake because discerning use of commercial materials

alongside the generation of learner-specific elements of a syllabus may

be a better route.

To do that five steps are needed:

This approach to syllabus design, which combines generic material with that which is targeted more finely to your learners, their personalities, their needs and your understanding of how to meet them, seeks to avoid the two most obvious dangers of coursebook-driven teaching by:

- injecting variety of approach, techniques, topics and materials so lessons do not follow the same sequences and employ the same procedures time after time in a predictable and ultimately demotivating way.

- ensuring that the core needs of the group and even the needs of individuals within it can be addressed, getting away from what temporally, physically and culturally distant authors and editors think your students are like.

| Related guides | |

| needs analyses | for a guide to discovering your learners' needs |

| CLIL | for more on content and language integrated learning (teaching English by using it to teach other parts of a curriculum) |

| task-based language teaching | for more on the approach |

| Krashen and the Natural Approach | the five central hypotheses, The Natural Approach in practice and criticisms of the theory |

| motivation | Gardner's four motivational categories, Expectancy Theory and Task, Institutional and Global motivation |

| assessing course materials | the guide to how to evaluate and assess coursebooks |

| The history and development of English Language Teaching | the ways in which theories of language and theories of learning have developed and informed ELT methodologies |

| Communicative Language Learning | for more about the dominant approach and theories of language |

| some alternative approaches | including considerations of syllabus-free approaches |

| lexical approach | for more on what a syllabus might contain in this methodology |

| post-method methodology | for a guide to the reasons many are dissatisfied with any single approach to teaching and learning (including syllabuses and coursebooks) |

References:

Brumfit, CJ & Johnson, K, 1979, The Communicative Approach to

Language Teaching, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hutchinson, T & Waters, A, 1987, English for Specific Purposes:

a

Learning Centred Approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Jordan, RR, 1997, English for Academic Purposes: a guide and

resource book for teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Nunan, D, 1988, Syllabus Design, Oxford: Oxford University

Press

Nunan, D, 1991, Communicative Tasks and the Language Curriculum,

TESOL Quarterly Vol. 25, No. 2, Summer 1991 279 – 295

Prabhu, NS, 1984, Procedural Syllabuses, in Read, J.A.S.

(ed.) Trends in Language Syllabus Design. Singapore: SEAMEO

Regional Language Centre

Sheldon, L, 1988, Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials, English Language Teaching Journal,

42/4, Oxford: Oxford University Press

The British Council, 2013, The English Effect, British Council

2013 / D096

White, RV, 1988, The ELT Curriculum: Design, Innovation and

Management, Oxford: Blackwell

Wilkins, DA, 1976, Notional Syllabuses, Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Willis, D, 1990, The Lexical Syllabus: A New Approach to Language

Teaching, London: COBUILD

Yalden, J, 1987, Principles of Course Design for Language

Teaching, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press