The history and development of English Language Teaching

|

Why the history lesson?

|

If you would understand

anything, observe its beginning and its development.

Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE)

|

Definitions of methodology |

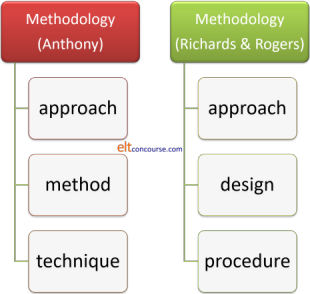

There are two common ways to define methodology in English Language Teaching and, graphically, this is how they look:

The left-hand set was developed by Anthony in 1963. The right-hand set was developed from Anthony's definition later and appears in Richards and Rogers, 2001. Briefly:

- Approach

- For Anthony, an approach was simply a

set of principles or ideas about the nature of language learning

For Richards and Rogers it was similar but explicitly divided into theories of what language is and theories of how learning a foreign language happens.

The second of these definitions has the advantage of being quite explicit. - Method or Design

- For Anthony, method described the plan for the presentation

of language which is consistent with the approach.

Richards and Rogers' concept of design is somewhat broader and covered the practical implications in the classroom: syllabus design, activities and the roles of teachers and students

These are not all that different but again, the latter one is more explicit. - Technique or Procedure

- Technique, for Anthony, was simple any teaching trick or way

of doing something in the classroom such as eliciting,

approaching a reading text, encouraging authentic speaking,

drill and so on.

For Richards and Rogers, too, the term procedure refers to what we see happening in the classroom when a particular approach and design are implemented, day to day.

It actually doesn't matter all that much which breakdown you accept. Both are fairly arbitrary and subjective ways of breaking down a complex area.

|

Once upon a time ... |

The authority in this area is Howatt (1984) and he traces the

development of English Language Teaching far further back than most

people realise it goes. He records the use of dialogues, often parallel

translation ones, to demonstrate rather than inform.

Here's an example, taken from a set of materials enabling French

speakers (probably Huguenots who fled to England from France in the late 17th and

early 18th centuries) to compare the English way of expressing things

with their own language.

It is from Guy Miège (1685), Nouvelle méthode pour apprendre

l'Anglais. It could just as well be used by an English

speaker to learn French.

| Si l'on veut fumer du Tabac, on y trouve non seulement les Pipes & la Bougie, mais aussi en quêques Endroits le tabac même, gratis. Le Caphé & le Thé pavent pour tout. | If you will take Tobacco, you find not only Pipes and Candle, but in some places the Tobacco, gratis. So that the Coffee, or the Tee, pays for all. |

| V. Combien se vend donc la Tasse de Caphé, ou de Thé? | V. How much do they sell a Dish of Coffee or Tee? |

| M. Un sou. | M. A Peny a Dish. |

| V. En verité, cela est commode. | V. Truly, 'tis mighty convenient. |

And so on. This is not too far removed from many modern course materials which, without the translation in many cases, set a conversation in a common environment to allow the language to be demonstrated in action. Truly, 'tis a mighty convenient way to present language for analysis.

|

Grammar-translation approachesThe 19th century saw the first fundamental change. The importance given to the study of Latin and Greek as a way of accessing ancient literature bled over into the teaching of modern languages, too. The approach had (and, indeed, still has) five main strains:

|

|

The aim of the approach was primarily to allow the student access to the literature of the target language. Few people travelled widely and there was little need or opportunity to encounter native speakers or to communicate in the way that, e.g., Huguenot immigrants needed to find the cheapest coffee shops with free tobacco. Grammar translation is not, as some fondly imagine, a thing of the past. Its influence is widely felt. Many self-help teaching manuals (such as the earlier versions of the popular Teach Yourself ... series of books) involve the setting out of grammar rules, followed by a list of translated lexis to learn and then exercises (including translation) to practise what has been studied. Secondary (and even primary) schools around the world adopt the approach consistently and it may have been part of your learning experience.(Since 2012 the Teach Yourself series has abandoned the presentation of rules in favour of a so-called 'discovery method' which encourages the learner to figure out the rules from the examples. More later on the difference in these approaches to rule-learning.) |

|

|

Reactions to grammar-translation approaches and the Reform Movement |

Starting in the 19th century and continuing to the present, the grammar-translation approach has been criticised primarily because it focuses on form at the expense of meaning and communicative ability. Many early critics drew on analogies with how we learn our first language. By the end of the century, the Reform Movement's fundamental principles had been established by Henry Sweet as:

the primacy of speech, the centrality of the connected text as the kernel of the teaching-learning process, and the absolute priority of an oral methodology in the classroom (in Howatt, op cit.: 171)

Methods arising from the Reform Movement include two which are still significantly influential:

- The Natural Method which sought to emulate the ways in which children learn their first language and

- The Direct Method which arose from it and was popularised by Maximilian Berlitz and still in use in many schools. The Berlitz Method is now a registered trade mark. The Direct Method was so called because it insists that only the target language is used from day one of the course and meaning is conveyed by pointing, gestures, tone of voice etc. Of course, today, many methods take a similar approach, denigrating or forbidding the use of translation.

|

The Oral Approach or Situational Language Teaching |

Early in the 20th century, there arose in the UK an approach to teaching which relied on two principles:

-

That language should be taught and presented in a social context: a situation.

-

That the focus of the syllabus should be on word order, inflexion and the distinction between structural words and content words. (For more on this distinction, see the guide to function words on this site.)

The outcome of this was productive and

many teaching materials still rely heavily on

presenting language, often via dialogues, in settings such as 'at

the coffee shop' or 'in the station' etc. You are probably

familiar with some of them.

As two of the founders of the approach state

The language a person originates ... is always expressed for a

purpose.

(Frisby and Halliday in Richards and

Rogers (2014: 48).

The approach's view about how languages are learned rested on

the same basis as the audio-lingual approach (see below).

|

Audio-lingualism: a scientific approach |

Richards and Rogers (op cit.: 13) describe the

Direct Method as

the product of enlightened amateurism

but

change was on its way, as was a world war.

In 1942, the USA found itself in urgent need of a large number of

foreign-language speakers and turned

to academia for help.

At the time, powerful twin views of language and learning were

emerging in the United States and so was born The Army

Specialized Training Program, a fast and scientifically grounded

approach to teaching languages.

|

Twin theories of audio-lingualism |

|

In order for a methodology to be truly recognisable as such, it is arguable that it needs to have a consistent theoretical basis. Audio-lingualism's claim to have these rests on:

|

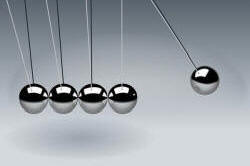

Behaviourism is the theory of learning that still underlies how you train your dog or drill your learners' pronunciation. It can be visualised like this:

Briefly, and somewhat unscientifically:

- The process starts with a stimulus, say, a question from the teacher such as Where did you go yesterday? put to the organism (in this case, a learner of English). The stimulus can elicit a variety of responses but only the 'right' one will be reinforced.

- So, for example, if the organism responds with I go to the cinema the teacher will negatively reinforce it with No, that's wrong or simply not reinforce it by saying nothing.

- If, on the other hand, the organism produces the preferred response, I went to the cinema the teacher will reinforce it with Yes, that's right! (preferably in a loud and enthusiastic voice because the strength of the reinforcement is critical in instilling the correct habit). In this case, the reward is the teacher's approval but it could just as well be a chocolate biscuit.

- Enough Stimulus > Response > Reinforcement cycles will see the habit instilled and the language acquired.

Audio-lingualism is still a very influential approach. It

underlies drilling language in the classroom, setting mechanical (and

not so mechanical) exercises, exposing learners to patterns of language,

repetition of language and much else. The concept that good

language habits are born of repeated practice and exposure is by no

means unknown in almost all classrooms.

The idea that learners can figure out rules unconsciously for

themselves, given enough data to work on and exposure to language

samples that exemplify the rule we would like them to acquire, underlies

much of modern inductive learning approaches in the classroom.

More on the meaning of 'inductive' follows. But first, we need to

consider the criticisms which have been levelled at behaviourism.

Unsurprisingly, this approach to language learning (or any

understanding of behaviour in humans) has not been without its critics.

For a cogent and compelling one, see Koestler (1964).

The most serious critic of behaviourist approaches to language learning

remains Chomsky and it is to him we turn next.

|

Chomsky |

Noam Chomsky, an American linguist, is probably most famous

in language teaching for his work on transformational generative

grammar but it is his aversion to behaviourist learning theories

and structural linguistics which concerns us here.

He is famously cited as asserting (2003:349):

Language is not a habit structure.

Ordinary linguistic behaviour characteristically involves

innovation, formation of new sentences and patterns in

accordance with rules of great abstractness and intricacy.

What this means is:

- structural linguistics is inadequate to describe language and

- behaviourist learning theories are inadequate to describe how language is learned.

In other words: it's all wrong.

The key criticisms of behaviourism are fourfold (and they aren't all Chomsky's alone):

- Unpredictability

- How do you know what someone will say when presented with a stimulus? In our example, above, of the teacher eliciting the past tense of the verb go, what happens if the learner (or the organism) produces the perfectly correct Somewhere I've never been before or What time last night? or any other of many thousands of possible responses.

- Reinforcement

- Reinforcement does not occur regularly. Parents and others

regularly approve statements that are true (or cute) rather than

grammatically accurate. For example, in response to seeing a

horse if a child produces Look at the big doggy!, many

adults might respond positively because it's a cute and endearing

thing to say, albeit wrong. How, then, do children learn to

see where the meanings of words start and stop?

Equally, if a child says It a horse! in response to a follow-up question, adults might well be tempted to approve because it's right rather than correct the grammar. - Response strength

- is variable. We don’t always shout our approval. In fact, it's sometimes more effective to reply in hushed, awe-struck tones.

- Innovation

- Speakers of all languages consistently produce novel and unique utterances. For example, I may say There's a green dodo in my cantaloupe juice. Whatever you may think of my state of mind, you will understand what I am saying although you and I have never heard or said it before. If language is a habit structure, how did I do that? By the way, Chomsky's famous example of this was Green ideas sleep furiously.

The criticisms of structural linguistics are quite technical and complex. Here we will take just two:

- Ambiguity

- Take this famous example: Visiting aunts

can be boring

It could mean:

Aunts who visit can be boring

Visiting your aunts can be boring

If we want to understand the sentence we need to go beyond the rules of structural linguistics and consider what is called 'deep structure'. We do this by considering whether the word visiting is a participle adjective describing aunts or a gerund of the verb visit. - Rules of use

- This is a famous citation from Hymes (1971:278):

There are rules of use without which the rules of grammar would be useless.

For example, if I say It's cold in here I may be asking you to shut the window, telling you to put the heating on, advising you to get dressed or any number of other things and we don't know what it means solely by applying grammatical rules. We use rules of use. See the guide to form and function for more.

For much more on Chomsky, his criticisms of Structural Linguistics and something on the Language Acquisition Device and Universal Grammar, follow the guide to Chomsky.

|

Cognitivism |

Theories of cognitivism (as opposed to behaviourism) underlie much of post-behaviourist language teaching.

Cognitivism is concerned with the investigation of how people think – their internal mental states. In our field, this means thinking about how people process language and information to construct dependable rules for its use.

If you are given a rule and then told to apply it by deducing what the correct form should be, you are using your brain to extrapolate from a rule to a single example of language.

For example, if you are told the rules to form regular past tenses in English and then asked for the past tense of smoke, live, pack etc., you should be able to come up with the correct forms.

That's deductive learning.

If, on the other hand, you are

given the examples first (pack-packed, live-lived,

smoke-smoked, type-typed, garden-gardened etc.) and then

asked to state the rule you could use your brain to generalise

that verbs ending in -e take -d and those not

doing so take -ed.

That's inductive learning.

This is a fundamental distinction.

There are those who will aver that one or the other is 'better'

but that's an oversimplification. It may be that some of

us are better at one form of thinking than the other or that

some forms of problem are more susceptible to being solved by

one way of thinking than the other. It may also be a

combination of the two.

Either way, looking at learning through this lens focuses on the

fact that humans make sense of the data they are given by making

hypotheses about the truth. That's a cognitive view of

behaviour and learning.

|

Where next? |

Taken together, the following led to a rise in the 1960s and 1970s of a new approach to language teaching:

- criticisms of structural linguistics (and the growth of descriptive rather than prescriptive grammars)

- criticisms of behaviourist theories of learning (and an emphasis on cognition)

- a recognition that language is primarily a means to communicate (and not only a set of grammatical rules and lexis)

- a recognition that learners need to know how to deploy the language they are learning in order to communicate

That approach is usually called Communicative Language Teaching or CLT. It has become so dominant that there is a guide devoted to it linked in the list of related guides at the end.

| Related guides (some linked above) | |

| Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) | a separate guide devoted to the most ubiquitous methodology |

| Task-Based Learning | an approach often seen as a subdivision of CLT |

| The Natural Approach | Krashen and Terrell's approach |

| Some alternative approaches | a guide which includes approaches such as Total Physical Response, Dogme and others |

| The Lexical Approach | a guide to an approach which focus on lexis rather than grammar |

| Chomsky | a guide to some of Chomsky's most influential theories |

| form and function | a fairly basic guide to the differences |

| syllabus design | the design of a syllabus often reflects a view of the best approach to teaching it |

| first- and second-language acquisition theory | an overview of the theories of how we acquire our first and learn a second language |

There's a test on this that you can try if you like but you are not expected to have remembered all this for the purposes of most training courses. You are, however, expected to know about it.

References:

Berlitz: more information at www.berlitz.com

Chomsky, N, 1957, Syntactic Structures. The Hague/Paris: Mouton

Chomsky, N and Otero, C. P, 2003, Chomsky on Democracy & Education, Psychology Press

Hymes, D, 1971, On communicative competence. In Pride, J & Holmes J (eds.), p 278, Sociolinguistics, London: Penguin

Koestler, A, 1964. The Act of Creation. New York: Penguin Books

Howatt, APR, 1984, A History of English Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Richards, JC, and Rodgers, TS, 1986, Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Skinner, BF, 1948, Verbal Behavior, available from http://www.behavior.org/resources/595.pdf [accessed October 2014]