Idiomaticity

What springs to mind when you see these images? Click here when you have thought of 6 expressions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

- bite the bullet (suffer an unpleasant and unavoidable situation)

- I'm all ears (I'm listening carefully and am interested)

- a piece of cake (an easy and enjoyable task)

- burn the candle at both ends (work late into the night and begin again in the early morning, thus exhausting oneself)

- let the cat out of the bag (reveal a secret)

- pull someone's leg (play a joke on someone by telling a lie)

There are two important characteristics of the expressions

in black. What are they?

Click here when you have an answer.

- non-compositionality

- this simply means that you can't get the meaning of the expression even if you know all the words in it. There is no way (without clear context) to guess, e.g., what let the cat out of the bag means.

- fixedness

- all the examples of idioms above are fixed: you can't replace

any of the words (except someone in the last case with a

name or pronoun), you can't leave out any of the words and you

can't insert words.

You can, naturally, bite a stick, burn a hurricane lamp, let the donkey out of the stable, release the cat from the bag, bite the 6mm bullet and pull someone's ear but none of the expressions will have the same meanings as these examples.

For a little more on semantics and noncompositionality, consult the guide to semantics linked in the list of related guides at the end.

So, idioms are non-compositional and fixed. End of story,

right?

Not quite, no.

|

Definitions |

An early definition of an idiom comes from the linguist and teacher Henry Sweet (a major influence in the Reform Movement's reaction to grammar-translation approaches, incidentally). He stated:

The meaning of each idiom is an isolated

fact which cannot be inferred from the meaning of the words of which the

idiom is made up.

(Sweet, 1889:139)

Since Sweet's time, the area has been continually revisited by researchers interested in finding out what constitutes idiomaticity in languages and how the various types of idiom can be classified and analysed. What we have ended up with is a confusing muddle of terms, definitions and classifications which is, to say the least, unhelpful. You may, for example, come across any or all of the following terms if you research this area:

| figurative idioms or non-compositional metaphors | to refer to fact that we can often find a connection between figurative, idiomatic and literal meaning. It is for example, just possible to figure out what bite the bullet might mean with some knowledge of pre-anaesthetic surgery. Ditto, perhaps, with have an ace up one's sleeve |

| binomials | to refer to expressions such as time and again, Ladies and Gentlemen which occur as pairs of words, often with a fixed ordering |

| fixed expressions | to refer to idioms which are truly fixed such as an open and shut case |

| semi-fixed expressions | to refer to idioms where some flexibility is allowed. For example, you can throw in the towel but also throw in the sponge, both meaning surrender, and both derived from boxing |

| lexicalised expressions | to indicate that the expression functions as a single lexeme. For example, kick the bucket actually just functions as the verb die |

| opaque expressions | emphasising the fact that is often not possible to work out metaphoric meaning from literal meaning as it is with figurative metaphors. For example, chew the fat |

| frozen collocations | emphasising the fixedness characteristic of some idioms such as a can of worms |

| restricted collocations | referring to those which allow some flexibility but only within a limited range. For example, you can be a big/large/huge fish in a small/little/tiny pond |

| semi-idioms | to refer to anything which seems like an idiom, insofar as it acts like a single word, but is not completely opaque and fixed. One part of the expression has a figurative meaning not found elsewhere but the other part is 'normal' as in expressions such as pay attention or foot the bill |

It is not the suggestion here that such refinements are useless or

deliberately confusing but we are interested in classifications which

will be useful to us as English-language teachers rather than research

linguists so this guide will focus on two the central characteristics of

idiomatic language: fixedness and opacity

(or non-compositionality, if you prefer).

This will be at the expense of some precision so if you are looking for

more, there are references at the end to on-line, more scholarly

articles that you may want to read.

In some analyses, the definition of an idiom includes both fixedness

(the inability to change any of the components) and opacity

(non-compositionality) but both these phenomena exist on a scale from

fully fixed and opaque through semi-fixed and opaque to variable and

easily understood. The definition soon breaks down.

|

Origins |

Although this distinction is not necessary for teaching purposes, it is sometimes helpful in terms of memorisation to know the origin of the idiom one encounters. There are two possible sources (which often overlap):

- Fixed metaphor

Frequently, very influential texts in English, such as the bible, Shakespeare's works and others, contain metaphors which have come into everyday use and become fixed idioms. Some metaphorical uses are obscure in origin. Examples include:

heart of gold

laughing stock

wild goose chase

wear your heart on your sleeve

(all from Shakespeare)

at the eleventh hour

by the skin of your teeth

a millstone around your neck

the writing on the wall

(all biblical)

it gives me the creeps

go on the rampage

(both from Charles Dickens)

spill the beans

straight from the horse's mouth

let the cat out of the bag

count your chickens before they are hatched

out to lunch

just my cup of tea

(all obscure in origin but some may conveniently but speculatively be derived from some occupations) - Historical and specific register origins

Other idioms derive from certain registers: sport, the military, trade, sailing and so on and are often opaque without a certain amount of knowledge of the history of the domains. They are usually not completely opaque, however.

Examples include:

a sticky wicket (from cricket)

cover all the bases (baseball)

run with the ball (rugby or American football)

game, set and match (tennis)

a level playing field (many sports)

plant a seed (horticulture)

plough through (farming)

cut a deal (obscure but possibly from card games)

hit a snag (angling or river navigation)

a loose cannon (from naval warfare)

flash in the pan (musketry)

close ranks (army parade term)

half-baked (cookery)

cut and dried (herbalism)

sail close to the wind (sailing)

|

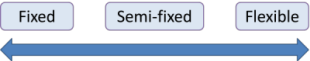

Fixedness |

This is not an on-off characteristic. Some idioms are more fixed than others, some are very flexible. Here's a cline for you to see what's meant. Where would you put the idioms on right in the cline on the left (if idioms they actually are)? Click on the image for some comments when you have an answer.

|

through thick and thin hammer and sickle aid and abet have a blast hit the sack off one's rocker call it a day assets and liabilities left, right and centre |

life or death back to the drawing board cut corners put all your eggs in one basket torrential rain wouldn't be caught dead miss the boat make the grade make the beds raining cats and dogs |

On the left hand end of the cline, we can arrange those idioms which are clearly fixed in which we cannot add words, replace words or delete words without changing the meaning entirely. These include:

- hammer and sickle, aid and abet, life or death

- These are fixed-order binomials, sometimes called frozen

binomials. You can't reverse the order without sounding

odd and neither part can be replaced to maintain the meaning.

Nor can you insert anything between the parts. When they

are nouns, such binomials are treated as singular in English (the hammer and sickle

is, thunder and lightning was

etc.).

They belong on the far left. - left, right and centre

- This is similar but is actually called a trinomial (for a

pretty obvious reason). Other examples are:

blood, sweat and tears; cool,

calm, and collected; win, place, or show; tall, dark and

handsome and so on.

True trinomials like these belong on the left of the cline. - call it a day, cut corners, put all your eggs in one basket, wouldn't be caught dead, miss the boat, make the grade, raining cats and dogs, through thick and thin

- These are all fixed idioms. The last of these (through

thick and thin) is often classed as a fixed

binomial. We can't vary the order of words, insert words,

replace words or delete words in these expressions. We

can't have

put all your eggs in one tray

miss the train

rain cats and monkeys

call it a busy day

cut sharp corners

if we want to retain the meaning.

Note, however, that even with fixed idioms, we can alter the tense and must make the pronouns agree (they called / are calling it a day, he missed / will miss the boat, she'll never make the grade etc.) Other structural changes are possible but very rare such as cut a corner but most are forbidden such as *put all your eggs in baskets or *make the grades.

They belong on the far left of the cline.

On the right we have the most flexible expressions and there are only two of these:

- torrential rain, make the beds

- These are strong collocations because there is a limited

number of possible substitutions with verb + the beds

or torrential + noun. We can, just possibly, have

do the beds and make up the beds and have

torrential waterfalls or torrential rivers but

it's hard to find more replacements. The other way round,

however, produces a wider range of possibilities. The verb

make collocates with an enormous number of nouns (mistakes,

haste, mess etc.) and the number of possible adjectives for

rain is also large (heavy, light, drizzly, hard, thin

etc.). However, some strong collocations are so

predictable as to constitute real idioms. For example,

We pay attention, a compliment and our respects but take an interest, offence, place etc. and give explanations, thanks and promises etc.

It is quite arguable that collocations of this sort do not fully qualify at all as idioms and won't be considered further here. There is a separate guide to collocation on this site, linked below.

The rest of the expressions fall somewhere in the middle of the cline:

- have a blast, hit the sack, off one's rocker, back to the drawing board

- These all have alternates with the same or a very similar

meaning so they are semi-fixed idioms. We can have:

have a hoot

have a whale of a time

hit the hay

off one's trolley

back to square one

which all carry the same sorts of meaning, although they are sometimes stylistically different. Expressions such as these only have a very limited number of alternatives and they belong on the mid-left of the cline. They share other characteristics with true fixed expressions in not allowing deletions or insertions but a severely limited range of alternate words is possible. - assets and liabilities

- This is rather an unusual case because it is a binomial but the

ordering is not fixed (although this is the preferred one).

Other examples of binomials which do not have fully fixed ordering

include:

salt and pepper

see and hear

friends and family

etc.

There is usually a preferred order with all binomials but the reasons for it are complex. See Benor and Levy (no date) for a technical discussion.

There is an interesting exception to fixedness.

Some idioms and even binomials which are normally considered wholly

fixed can be modified with intensifiers. It is possible,

therefore, to have:

I have been rushing hither and

bloody yon all

day

I smell an

extremely large rat

I've missed the

damn/an important boat

have a

total/absolute/complete blast

etc. In particular, the so-called taboo words, bloody,

bleeding, damn etc., are used in this way.

Idioms may be flexible to a certain extent, then, but the flexibility is also analysable by type.

- Conjugation

Idioms which contain verbs are frequently conjugated to conform to the normal rules so, e.g.:

pass the buck

may be

passes, passed, is passing the buck

and so on and the verb can be nominalised as in:

I resent your passing the buck

Pronouns will change in the normal way and may be accompanied by other changes, e.g.:

She bit off more than she could chew

He has bitten off more than anyone could chew - Passivisation

Such idioms can also be made passive so we can allow

They have cooked the books

and

The books have been cooked - Insertion of words (usually adjectives or adverbs)

right at the eleventh hour

teaching new tricks to a very old dog

by the absolute skin of my teeth - Re-formulation

We need a level playing field → We need to level the playing field

She has a heart of gold → Her heart is of pure gold

|

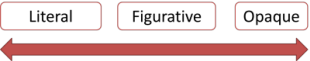

Opacity or non-compositionality |

Again, there's a cline because there are levels of opacity and

transparency. The image below separates them into those whose

meaning is obvious (literal), those where it can be deduced

(figurative uses) and those which are wholly opaque.

As you did above, locate these expressions on the right somewhere on the

cline on the left and then click the image for a commentary.

|

barking up the wrong tree a bitter pill to swallow by the skin of one's teeth bread and circuses kiss and tell heads or tails spick and span holding all the aces at a snail’s pace |

a dime a dozen bite off more than one can chew cut the mustard bob and weave under the weather hot and bothered research and development come rain or shine Tom, Dick and Harry |

Very few of these idioms are going to be on the

far left of the cline. If they were, they would hardly qualify as

idioms at all.

So, we have the first group of idioms whose meaning can be worked out

quite easily from their literal interpretation or whose meaning

is literal, in fact.

- heads or tails, a dime a dozen, research and development, at a snail's pace

- These are the most literal. It is easy to work out what

they mean from understanding their constituents. Many bi- and

tri-nomials fall into this category:

knife and fork

law and order

salt and pepper

sick and tired

red, white and blue

sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll

etc. Many do not have transparent meanings, however, such as

I'm all fingers and thumbs

It's neither fish nor fowl

Most idioms do not fall into this category.

The figurative section is the most crowded and it's a matter of opinion whether an expression falls to the left or right of the centre of the cline.

- barking up the wrong tree, a bitter pill to swallow, kiss and tell, holding all the aces, bite off more than one can chew, hot and bothered, come rain or shine

- In many of these sorts of expressions, only one of the items is

used figuratively so it's possible to work out what's meant.

In others, it is a short step from the literal to the metaphoric

meaning. For example, imagining a picture of a dog barking up

the wrong tree immediately allows you to make the jump to the

metaphorical meaning of barking up the

wrong tree. Equally, if you know something about

many card games, you'll know that

holding all the aces is likely to lead to a win.

Even kiss and tell needs

little context for you to understand its meaning.

With binomials and some other idioms, it's possible to assume that the terms are synonyms or antonyms of sorts and understanding one allows you to understand the whole. hot and bothered and come rain or shine fall into this category.

Finally, there are the wholly opaque idioms:

- by the skin of one's teeth, spick and span, cut the mustard, bob and weave, under the weather, Tom, Dick and Harry

- All these are opaque and you'd have to be very lucky to guess

their meaning even with context to help. Many idioms are like

these and they have to be learned as single units of meaning.

There are also a number of common binomials in which one or both items is only seen in that context. The example here is spick and span but others include:

to and fro

harum-scarum

helter-skelter

hem and haw

nip and tuck

etc.

|

The relationship between fixedness and opacity |

There is a tendency for these two characteristics to rise and fall together. In other words, the more fixed and inflexible the expression, the more likely it is to be opaque in meaning and vice versa.

We can find low fixedness with some expressions but they are likely

to be quite literal in meaning. For example,

as old as ... can be followed

by a number of expressions (God, the hills, Noah etc.) but

opacity is also low.

Similarly, strong collocations such as

a pronounced accent are not firmly fixed (we can have

strong, broad etc. as the adjective with roughly the same meaning)

but they are usually easy to understand (if not to learn).

On the other hand, an expression such as off one's rocker has quite high fixedness (there's only one conventional alternative to rocker, trolley) and it is also quite high in opacity. Extreme cases of fixedness are also, often, extreme cases of opacity. Expressions such as let the cat out of the bag are both opaque and fixed as are binomials such as helter-skelter.

There are, nevertheless, instances, especially with binomials, of low

opacity and high fixedness. In other words, they always occur

together and in the same order but are straightforward to understand.

Examples are:

here and there

hand in hand

dead and buried

etc.

The moral?

Whenever we find a highly opaque expression, the way to bet is that it

is also firmly fixed. The reverse is not always true.

Here's a graphical representation of that. Before teaching idioms,

it is worth 5 minutes of the planning time to consider where in the

matrix the target language items fall.

|

|

Binomials and trinomials |

Because these are so common in English, they merit a short section to

themselves. Many of these items are worth teaching as single

lexemes because they are handy language chunks, they are extremely

common and they are not easily paraphrased.

There are some general characteristics of binomial expressions:

- They consist of two lexical items belonging to the same word

class so they are, noun + noun, verb + verb, adjective +

adjective, adverb + adverb. Examples of the four main

sorts are:

He has lived here man and boy

You can take it or leave it

And that's the truth, pure and simple

I will do it sooner or later

(Rarely, the two items are not of the same word class but follow similar structural forms so, for example:

We were home and dry

in which home is an adverb and dry an adjective but both are joined to the subject by the copular verb. That is probably not something with which to trouble your learners.) - Some are literal (apples and oranges etc.), some are figurative (the chicken or the egg etc.) and some are wholly opaque (milk and honey etc.).

- Some, such as helter-skelter, super-duper etc., contain words found nowhere else.

- When two nouns are joined, the resulting expression is

often singular, e.g.:

Fire and brimstone is all he shouts about

Thunder and lightning is on its way

but, if the nouns are already plural, that is not the case:

His eyes and ears are everywhere

The stars and stripes are flying over The White House - The order of the items is usually fixed although with some,

reversal has no effect. We can have:

She worked day and night

and

She worked night and day

We allow

I'll do it sooner or later

but not

*I'll do it later or sooner - The tenses and numbers of items are normally retained in

both items so we get, for example:

It's done and dusted

It comes with many bells and whistles

I'll name and shame him

There will be some naming and shaming

They were named and shamed

etc. and:

*for all intent and purpose

*It's time to cut and be running

are not encountered. - The items are frequently joined with the coordinator and but there are other possibilities including: but, or, either ... or, neither ... nor, to, after, by, in.

- Often the items rhyme or are, more often, alliterative as

in, e.g.:

make or break

high and dry

house and home

do or die

etc.

In some, a phenomenon called assonance is discernible so for example, a stressed vowel will be the same in both items or a consonant duplicated with different vowels as in harum scarum or tittle-tattle. - Because binomials operate as single lexemes, they are

subject to the collocational forces as all other lexemes so, for

example:

high and dry collocates strongly with the verb leave

high and low collocates with verbs such as look (for), search, hunt and seek

dead and buried collocates with nouns such as ideas, proposals, suggestions, schemes and plans

and so on. - Binomials often intensify, especially reduplicative ones,

so, e.g.:

She went from strength to strength

Ones in which the two items are synonyms have the same effect:

He's at my beck and call

and, perversely, antonym pairs also intensify:

We searched high and low, in and out, in each and every part of the house

Here's a selection.

Fuller lists with some doubtful inclusions are available via a web

search.

joined with coordinators (and or or/neither ... nor etc.)

| above and beyond airs and graces alive and kicking all or nothing an arm and a leg apples and oranges assault and battery back and forth ball and chain beck and call beer and skittles bells and whistles for better or worse bits and bobs bow and arrow by and large cat and mouse the chicken or the egg cut and dried cut and run day or night dead and buried dead or alive divide and conquer do or die down and out each and every eyes and ears far and wide fast and loose fingers and thumbs fire and brimstone first and foremost forever and a day free and clear fight or flight (neither) fish nor fowl fun and games (come) hell or high water (neither) here nor there hit or miss hale and hearty hard and fast hearts and minds here and now high and dry high and low home and dry hope and pray |

horse and carriage intents and purposes kill or cure kill or be killed knife and fork law and order love nor money lo and behold loud and clear make or break man and boy milk and honey more or less nip and tuck nook and cranny nuts and bolts odds and ends pure and simple pepper and salt (colouring) rags to riches rain or shine research and development room and board sink or swim sooner or later take it or leave it salt and pepper (seasoning) seek and destroy short and / but sweet sick and tired slash and burn smash and grab snakes and ladders stand and deliver supply and demand sweetness and light tables and chairs tar and feather tea and crumpets thunder and lightning time after time to and fro tooth and nail touch and go trial and error up and about vim and vigour wait and see wine and roses |

with reduplication

The term reduplicate is a slight misnomer because the words are

duplicated, not reduplicated.

| again and again all in all around and around arm in arm back to back bit by bit bumper to bumper by and by cheek to cheek closer and closer coast to coast day to/ by day elbow to elbow end to end dog eat dog from ear to ear an eye for an eye eye to eye face to face hand in hand head to head heart to heart higher and higher horror of horrors less and less |

little by little lower and lower man to man more and more mouth to mouth neck and neck never say never nose to nose on and on out and out over and over round and round shoulder to shoulder side to side step by step strength to strength through and through time after time (from) time to time two by two toe to toe up and up wall to wall for weeks and weeks woman to woman |

with rhymes or similar sounds

These are often considered a subset of reduplicate phrases but exactly where the border is between a reduplicative and these examples lies is not always easy to determine.

Parts of the words are clear duplicated and the words often rhyme, a

phenomenon encapsulated in the alternative name, ricochet words.

The use or not of a hyphen is often idiosyncratic to the writer as is

whether some are written as one word.

| belt and braces box and cox chalk and talk chit-chat dilly-dally ding-dong double trouble even Stevens fender-bender flim-flam flip-flop hanky-panky harum-scarum helter-skelter higgelty-piggelty high and dry hire and fire hither and thither hobnob hocus-pocus hodge-podge hoity-toity horses for courses hubble-bubble huff and puff hurly-burly |

hustle and bustle meet and greet mish-mash namby-pamby name and shame near and dear nitty-gritty odds and sods out and about pell-mell ping-pong pitter-patter razzle-dazzle riff-raff roly-poly shillyshally time and tide tip-top tittle-tattle town and gown use it or lose it wear and tear willy-nilly wine and dine wishy-washy yea or nay |

patter is a reduction of pat-pat (to hit gently).

blabber is a reduction of blab-blab

paddle is a reduction of pad-pad

and so on.

The technical term for this phenomenon is that the word is a frequentative.

There are fewer of these and they almost always employ and as the coordinator. Examples include:

| beg, borrow or steal blood, sweat and tears cool, calm and collected eat, drink, and be merry ear, nose and throat gold, silver, and bronze guns, germs, and steel healthy, wealthy, and wise here, there and everywhere hook, line and sinker hop, skip and jump judge, jury and executioner left, right and centre lights, music, action |

lock, stock and barrel nasty, brutish and short planes, trains, and automobiles ready, willing and able reading, writing and arithmetic red, white and blue sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll sugar and spice and everything nice tall, dark and handsome Tom, Dick and Harry shake, rattle and roll this, that, and the other way, shape, or form win, lose, or draw |

hyphenation

Many binomials, especially those without a connecting conjunction,

are conventionally hyphenated so we get helter-skelter, willy-nilly,

harum-scarum and so on.

Others are only hyphenated when they are used adjectivally so we get,

for example:

It's a question of law and order

The price is subject to the influence of supply and demand

etc., because these are being used as nouns, but we have:

This is a law-and-order issue

It's a supply-and-demand influence

etc., because these are adjectival uses.

Trinomials exhibit the same phenomenon.

|

Fixed similes |

Similes explicitly compare two items, usually, in

English, with the as ... as formulation.

A number of these constitute a kind of idiom although in almost all

cases they are a) fixed and b) often (but not always) quite literal and

transparent in meaning. They include items such as:

as blind as a bat

as cool as a cucumber

as fit as a fiddle

as fresh as a daisy

as good as

gold

as keen as mustard

as light as a feather

as old as the hills

as regular as clockwork

as right as rain

as safe as houses

as strong as an ox

as stubborn as a mule

as thin as a rake

etc.

Such expressions, too, are often formed from rhyming (or near rhyming)

items and are often alliterative.

The main elements are also, again, usually given equal stress.

A secondary form for these fixed expressions employs the like

preposition. These are not adjectival so often it is a noun

being compared to another or a verb being used figuratively as in

eyes like a hawk

a face like a brick wall

a hand like a bunch of bananas

drink like a fish

smoke like a chimney

fight like cat and dog

eat like a horse

eat like a bird

run like clockwork

cry like a baby

spin like a top

work like a Trojan

be / behave:

like a child in a sweet shop

like a bull in a china shop

like a dog with two tails

like a headless chicken

like watching paint dry

They are almost totally confined to informal speech and writing.

Such clichés are often disparaged in more formal texts.

|

Style and register |

Most idiomatic language is stylistically informal and

inappropriate in a number of situations. Idioms are used

extensively in informal speech and writing (especially in

newspapers), however, so a knowledge of common ones is very helpful

for learners of English. Unfortunately, there are, by some

estimates, 25,000 of them in English.

In more formal contexts, idioms will often be avoided so we are

unlikely to find, for example:

Buckingham Palace announced that the Queen is under the weather

The government negotiators are reluctant to open a can of worms,

said the White House spokesman.

etc.

Learners of the language can be tempted to overuse idiomatic

language in situations where it is not appropriate or they can get

the meaning just slightly wrong and produce, e.g.:

*I'll do it willy-nilly

*The government isn't cutting the mustard for it

In common with many idiomatic expressions, bi- and trinomials are

often informal and common in spoken language.

A few, however, such as first and foremost, more and more,

intents and purposes and others are encountered in formal

writing and some are confined to specific registers such as

economics (supply and demand), the law (aid and abet),

education (reading, writing and arithmetic) or engineering,

politics and commerce (research and development, wear and tear, trial and error, ways and

means).

They are, to some extent, clichés and accordingly much used in

journalese.

The same considerations of grammar and form apply here as they do in

the teaching of any lexis.

It is important to make sure, then, that idiom presentation is set

in an appropriately context (both style and register) and that word class is considered along

with aspects of transitivity and so on.

|

Pronunciation |

-

Most binomials are evenly stressed with the coordinating item

being weakened. We get, therefore:

name and shame /ˈneɪm.n̩.ˈʃeɪm/

fun and games /ˈfʌn.n̩.ˈɡeɪmz/

tittle tattle /ˈtɪt.l̩.ˈtæt.l̩/

shoulder to shoulder /ˈʃəʊl.də.tə.ˈʃəʊl.də/

A few may operate like compound nouns and take the stress on the first element, e.g.:

near and dear (/ˈnɪər.n̩.dɪə/)

but stressing both components equally is more common. - Trinomials are lists but, because they are processed as

single units, the normal list intonation, with rises after each

item and a fall at the end, is compromised. We may get,

therefore, for example:

game, set and match

pronounced as

/ˈɡeɪmset.n̩.ˈmætʃ/

rather than

/ˈɡeɪm.ˈset.ənd.ˈmætʃ/

with the normal pause after the first item and equal stress on all the items.

More commonly, the stress on each item is retained but the intonation does not rise as it would in a list of less connected items:

beg, borrow and steal /ˈbeɡ.ˈbɒ.rəʊ.n̩.ˈstiːl/ - Many idioms operate as single lexemes and only one tone unit

is discernible so we have, e.g.:

I wouldn't be caught dead

/ˈaɪ.wʊdnt.bi.kɔːt.ˈded/

with only two stressed syllables.

Compare:

I wouldn't do that if I were you:

/ˈaɪ.wʊd.də.ˈðət.ɪf.ˈaɪ.wə.ˈju/

with four stresses. - Because of their single lexeme nature, idioms are spoken

rapidly as one chunk so syllable reduction and weak forms are

common. E.g.:

She's bitten off more than she can chew

is often pronounced as

/ʃiz.ˈbɪt.n̩.ə.mɔː.ðən.ʃi.kn̩.tʃuː/

with two syllabic consonants and weak forms (/ə/, /i/). See, too, the pronunciation of and in the binomial examples which is often reduced to a single syllabic consonant (/n̩/).

|

Teaching idiomatic language |

Too often, in coursebooks and study guides, idioms and idiomatic language are relegated to peripheral 'Useful phrases' boxes and then ignored. That's a great pity as it is almost impossible to become fluent in English without acquiring a fair number of idiomatic expressions. In fact:

Most students

are very interested in learning idiomatic language. They recognize

it as an area in which they have difficulties, and appreciate systematic

instruction.

(Irujo, 1986: 242)

There's nothing mysterious about this. We have to make the same judgements that we make when teaching lexis of any sort. In other words, we must consider appropriacy and style, range, learnability, frequency and so on. For more, see the guide to teaching lexis, linked below.

However, idioms and idiomatic language have some characteristics that make certain approaches more worthwhile and productive.

- Context

Idioms occur more naturally in informal story-telling language so that's a good place to situate them. Context will also help learners appreciate issues of style and co-text will often disambiguate meaning successfully. - Illustrations

Because idioms are so picturesque, it makes it comparatively easy to link them to illustrations (see the introduction to this guide for examples). - Figurative meaning

Group and pair-work to decipher figurative meaning is helpful because people see different things in language and have different mental metaphors so they can help each other significantly. Obviously, the more transparent the meaning is, the less hard the expression will be to understand and learn. - Retelling stories

Retelling exercises can be a powerful way of consolidating idiomatic language as can dialogue writing and creative story writing. - Translation

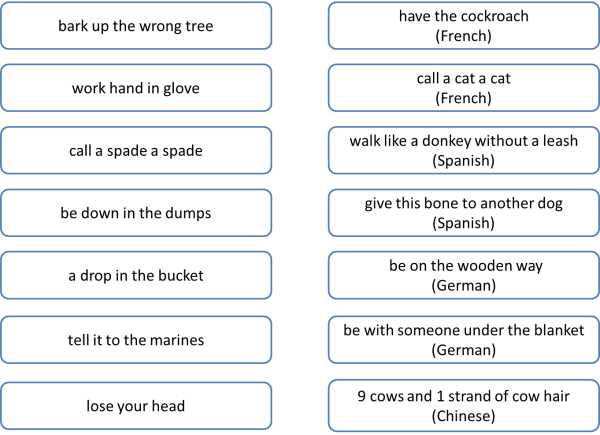

Idioms rarely translate exactly between languages but it is surprising how similar concepts are encoded in idiomatic language. For example, the expression it cost an arm and a leg is rendered in Spanish with something like it cost an eye of your face and in German, a hook in the matter means there's a fly in the ointment. All languages exhibit a rich and picturesque range of metaphorical meaning. It can be educational, interesting and fun to compare how meanings are encoded in various languages and that, too, can help retention.

Here are some examples for fun. Can you match the English idioms on the left to their equivalents in other languages on the right? Click on the image when you have an answer.

You can, of course, get your learners to make up quizzes like this and challenge others to find the English equivalent or figure out the meaning.

More teaching ideas can be found in Irujo (1986)

In the section for learners on this site, there are some exercises to do with idioms and binomials. Check the exercise index under vocabulary for more.

There is a very short test on some terms to help you recall all this.

| Related guides | |

| synonymy | for more on how this and related areas work with more on similes and metaphors (fixed and otherwise) |

| semantics | for a theoretical guide to meaning |

| teaching lexis | for some practical ideas |

| collocation | for more on this form lexical relationship |

References:

Barkema, H, 1996, Idiomaticity and terminology: a multi-dimensional

descriptive model, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Studia Linguistica,

Volume 50, Issue 2, pp. 125-160

Benor, SB & Levy, R, no date, The Chicken or the Egg? A

Probabilistic Analysis of English Binomials, available from

http://www.pdfmanuale.com/file/9GW/the-chicken-or-the-egg-a-probabilistic-analysis-of-english.html

[accessed January 2015]

lrujo, S, 1986, A piece of cake: learning and teaching idioms,

English Language Teaching Journal, 40 (3) pp. 236-242, Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Moreno, REV, no date, Idioms, Transparency and

Pragmatic Inference, available from

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/publications/WPL/05papers/vega_moreno.pdf

[accessed January 2015]

Sweet, H, 1889, The practical study of languages, London:

Oxford University Press (Reprinted in 1964)