Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning in language. It is a

sub-discipline of the science of semiotics which, roughly speaking,

is the study of meaning in general. There is, of course, a

distinction between meaning and meaning expressed via

language.

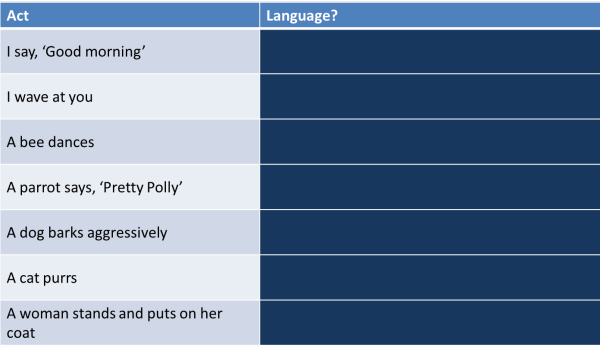

For example, which of the following represents meaning expressed

through language? Click on the table when you have an answer.

Whatever our personal views about whether dogs and cats

understand (or use) language or whether true language is a

phenomenon confined to humans, in what follows, we will be

discussing spoken or written language not the many other ways in

which meaning can be expressed. We will not, for example, be

dealing with body language but what follows does apply to the

various sign languages used by people around the world.

There is a guide to language evolution, linked below, which contains

some consideration of whether language is confined to humans or may

be said to be used by other animals.

|

Words, lexemes and lemmas (or lemmata) |

The guide to morphology, linked at the end, takes trouble to distinguish between a word and a lexeme and explains why many tests for identifying what a word actually is fail. You should go to that guide for more detail.

Here we will simply note that the term word applies in

this guide to any meaningful item in English which can be made by

applying the normal rules of morphology. By this definition,

the following are lexemes even when they contain more than one word:

The European Union, Mars, washing machine, happiness,

undoability, redefinability, colourlessness, go on, look

forward (to)

Not all of these will be found in a standard dictionary, of course,

but that doesn't stop them from carrying a single significance and

functioning as words in English.

Strictly speaking, a lexeme is often defined as a set of related forms of the same word so, e.g., speak, speaking, spoken, spoke are all various forms of the single lexeme speak.

A lemma is what dictionaries use as headwords from which other forms are derived. You would not, for example, expect all the forms of the lexeme speak to have a separate entry in a dictionary. You would simply go to the lemma and from there discover, perhaps, that the past tense of the verb is irregular.

|

What does mean mean? |

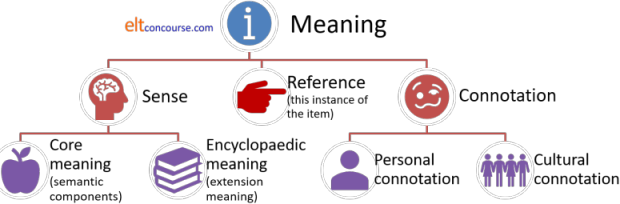

There are three fundamental forms of meaning.

- Sense

This refers to a word's general significance.

For example, we can probably agree on the sense of the word coin. The word, as a noun, means a small metal unit of currency. This is the word's sense or its denotation.

One word can have a range of senses in which it is used. For example, coin can be a verb (with a number of meanings) and the word bank can refer to a business that deals with money, the side of a river, a verb meaning rely and a verb meaning deposit money. All of these are senses (or denotations) of the word. For more, see the guide to polysemy, linked in the list of related guides at the end. - Reference

This refers to the actual thing I mean (or the action etc. but for simplicity's sake, we'll focus on nouns). In other words, it is this instance of the word's use.

For example, if I say, The coin on the book, I know (and so do you) that I am referring not to coins in a general sense but to a particular one I have in mind. However, just by looking at the words, we have no idea what exactly I am referring to and in a different setting the referent (thing referred to) may be different. - Connotation

This refers to a second level of meaning above denotation and is often personally or culturally determined. For example, the words quack and doctor carry the same sense (medical practitioner) but mean very different things. The same can be said of a whole range of near synonyms such as youth-teen, child-brat, newspaper-rag, speech-sermon, dirt-filth, police officer-copper-cop and so on.

The distinction between denotational and connotational meaning goes under a variety of guises in the literature including extension meaning vs. intention meaning, definitional information vs. contextual information and core meaning vs. encyclopaedic knowledge.

The last of these is the route taken below.

Fuzziness

Before we leave a discussion of what words mean we need to deal

with the borderlines of meaning. For example, we may know what

we understand as the distinction between related verbs such as

climb and scramble but identifying exactly at which

point a scramble becomes a climb and vice

versa is quite difficult and will probably vary between

speakers of the language.

We may equally be comfortable distinguishing, for example between

these related terms:

claw vs. talon

tooth vs. fang

tree vs. bush

hill vs. mountain

fire vs. blaze

red vs. pink

ill vs. poorly

walk vs. run

expect vs. anticipate

and so on.

However, precisely where we draw the line is clearly debatable.

Partly, we are discussing here something called troponymy.

Because, for example, walk and run (as well as

amble, stroll, wander, gallop, trot and so on are ways of

moving on legs. In other words, they have a relationship of a

special kind of hyponymy.

The guide to lexical relationships, linked at the end, has a little

more on hyponymy and troponymy.

Often, we decide where the borders between meanings are on the basis of:

- contrasting the meanings with other related word so, for example, we may distinguish between red and pink by deciding whether it is a colour more closely approximating to rose or crimson.

- the context in which it occurs, preferring fang for the tooth of a large carnivore and tooth for that of a smaller animal or person.

- comparison with a prototype so we decide where the line is drawn between a mountain and a hill by simply comparing the size, characteristics and shape of what we see to a well-known prototype of a mountain such as Mont Blanc.

Meaning is, therefore, partly dependent on sense relations or categories of related meaning. This is the meat and drink of semantics.

Some words, of course, do not exhibit any obvious fuzziness and

they are mostly those which are carefully defined in certain fields

or are associated with particular objects. Examples of such

words are:

aspirin

carbohydrate

triangle

logarithm

DVD

server

etc.

However, among experts even more than among lay people some terms

may be the object of heated debates and the precise point at which a

planet such as Pluto is downgraded to that of dwarf planet, for

example, was only settled in 2006 and many non-astronomers will

still refer to it as the ninth planet of the solar system.

|

Two distinctions of meaning |

|

Core meaning |

Allied to the distinction between denotation and connotation is

the concept, variously described and classified, of some sort of

core or basic meaning of a word and its meaning for whomever reads

or hears it.

Here we need to distinguish, as Aristotle did some time ago, between

a word's essential meaning and its reference meaning.

Aristotle referred to essence: the

essential qualities of a thing without which it loses its identity.

For example, if I hear:

Look. There's a dog in the garden

I will not randomly peer through the window trying to understand

what is meant but will immediately be alert to spot a four-legged,

furry object which matches my mental picture of dogness.

I have probably never seen the dog in question but I will

immediately recognise it because I have a set of mental constructs

which applies only to dogs. I will, therefore, not waste my

time looking at trees, ponds, unicorns or elephants because that is not what I

am primed to see.

What I am looking for is something which contains the semantic components of the word dog. I.e., it is animate, furry, four legged and of a certain size (a somewhat variable component).

How we do this is slightly mysterious but to try an explanation,

here's an example. Given a resource like this,

if someone says:

Please give me that cup

it will not be difficult for most people to recognise the object

which is being spoken about from a range of possible containers and

other objects in sight even if the cup in question has never been

seen before. To do that, people need a mental prototype of a

cup which distinguishes it from other sorts of objects. And to

do that, we assign characteristics (either positively or negatively)

which we use to distinguish cups from other objects. For example,

we may select the following as part of the essence or core meaning of the term

cup:

| Quality for cups | Yes | No | Maybe |

| designed to hold liquids |

|

||

| made of china or porcelain |

|

||

| made of glass |

|

|

|

| for hot liquids |

|

||

| roughly cylindrical |

|

||

| plastic |

|

||

| of any colour |

|

||

| transparent |

|

||

| with a handle |

|

||

| holding less than .5 litres |

|

||

| with a saucer |

|

However, if someone says,

Please give me that glass

we will recognise it by a different set of prototypical features:

| Quality for glasses | Yes | No | Maybe |

| designed to hold liquids |

|

||

| made of china or porcelain |

|

||

| made of glass |

|

||

| for hot liquids |

|

||

| roughly cylindrical |

|

||

| plastic |

|

||

| of any colour |

|

||

| transparent |

|

||

| with a handle |

|

||

| holding less than .5 litres |

|

||

| with a saucer |

|

When it comes to more closely related concepts, speakers of a

language will often disagree about what to call something.

For example:

Would you like a cup or a mug of coffee?

Did she stroll or amble here?

In the first of these examples, we have two hyponyms which bear

some relationship to a hypernym such as

food container.

In the second of those two examples, we encounter a

relationship between words called troponymy. That is to say,

both the words amble and stroll are ways of

further defining the concept of walk. However,

exactly how the nature of strolling differs from that of

ambling, wandering, sauntering, rambling, mooching and so

on is quite obscure and native speakers of a language are unlikely

to agree completely about where to draw the lines.

For a little more on these two concepts, see the guide to lexical

relationships, linked in the list at the end.

To further complicate matters, individuals will vary in the characteristics they see as essential and those which are optional. Between cultures, variations will be even more obvious with German speakers, for example, often excluding potato from the general category of vegetable.

The selection will be made on the basis of choosing the object

which ticks most of the boxes and excluding those with forbidden

characteristics.

What we do, in the jargon, is to carry out a semantic or

componential analysis of,

in our example,

the terms cup and glass. When we do that, if

we are faced with two similar objects (or actions, adjectives or

whatever), we may use the optional

characteristics above to make our choice. So, for example, we

may exclude a container made of glass which has no handle in favour

of a glass one with a handle when we are searching for the cup in

question.

Alert readers will, however, have noticed a snag with an analysis like this: the distinctions are fuzzy at the edges. Some cups are made of glass, some glasses are made of plastic and so on. Aitchison, 1987, suggests that in addition to the prototypical features of the object, people also apply those characteristics with which they are most familiar so that, for example, speakers from certain cultural backgrounds may insist that all cups have handles and come with saucers but for others that distinction may not apply.

|

Encyclopaedic knowledge |

In addition to all this, there is a distinction between the core

meaning (what we have discussed up to now) and what is sometimes

called encyclopaedic knowledge or extension meaning which refers to

what we know about the word from our general knowledge of the world.

Schmitt, 2000: 27, provides the example of the term bachelor,

the semantic analysis of which would be +human, +male, +adult and

-married or, in other words, an adult, unmarried, male human.

The issue here is that while the semantic definition holds true,

there's a lot we know about bachelors which is not included.

As Schmitt points out, this knowledge includes the fact that

bachelors are often young, date women

and have exciting lifestyles and none of that

information can be captured by a purely semantic analysis because it

forms part of the schema that native speakers have, in certain

cultures, concerning the state of bachelorhood. As Schmitt

points out, the core definition of bachelor would include

a divorced, middle-aged man with

several children or a male

who is unmarried, but living with his partner but our

encyclopaedic knowledge might act to exclude such people from the

definition.

The issue is twofold:

- Core semantic features of a word will be limited and can be taught by exemplification and helping learners to notice where the word starts and stops and how the concept is distinguished from similar concepts (as in the difference between cup and glass discussed above).

- Encyclopaedic knowledge is open ended and varies between cultures and individuals within cultures. The schema which for each person is activated by encountering a word such as farmer, for example, will be variable and some individuals (and some cultures) may exclude, for example, someone who has a smallholding on which she works part time or a large landowner who lives in the city and rarely visits a farm.

Encyclopaedic knowledge, incidentally, is part of the ability to

recognise impossible collocation. For example, if we encounter

words such as lacy, silky, smooth, velvety etc., our

knowledge of the world tells us that they cannot be applied to any

noun in the whole English lexicon (of which there are over 85,000).

One cannot have, for example,

a velvety rhinoceros

simply because the animal doesn't come that way.

Equally, of course, we know that verbs such as assert or

enjoy cannot have inanimate subjects because tables and

houses etc. do not do these things. Poetically, we may allow

many kinds of odd combinations for effect, of course.

For more in this area of what is called suppositional or

pre-suppositional meaning. See the guide to collocation,

linked below.

|

Kinship terms and the packaging of information |

Core meaning and encyclopaedic knowledge is well exemplified when

considering kinship terms.

For example, in English the terms are relatively simple. We

can, for example, say:

He is my grandfather

That is my niece

That is her aunt

and so on.

From our encyclopaedic knowledge, we know that grandfather

is a male parent of someone's parents and we can define other

kinship terms in the same way: female offspring of a bother or

sister, sister of a parent etc.

However, when we ask what information is encoded in the terms, the

situation is somewhat rough and ready. When someone says, for

example:

That is my nephew

we know only that the person in question is one generation removed

(down the family tree) and is male. We do not know:

- whether the person is related to the speaker by blood or marriage

- whether the person is older or younger than the speaker

- whether the person is the son of a sister or a brother

- whether the person is the son of an older or younger sibling

- whether the person is a boy or a grown man

Equally, someone may say:

That is my uncle

and again, the details of the person and the precise family

relationships that exists remain unclear. In many

English-speaking societies, the man in question may not even be

related in any way to the speaker but the term uncle simply

denotes an older male friend of the speaker's parents. Even

less informative in this respect is:

That is my cousin

in which we do not even have access to the information about the

person's sex.

This is because languages encode the meanings that are socially

important and English-speaking culture, presumably, has seen no need

historically for the relationship details to be made clear.

Other languages will encode different data and make any or all of

the relationships (blood vs. marriage, older or younger, male or

female, connection to other family members and so on) clear in the

term that is chosen. Some, such as Sudanese, will be much more

informative and have words for cousin which distinguish

between

father's brother's children

father's sister's children

mother's sister's children

mother's brother's children

Others may be even less informative than English. Some

Hawaiian languages, for example, do not distinguish between sibling

and cousin at all.

Kinship terms are just one of the areas in which languages choose to encode what is culturally important to them. Some languages will have single words to describe events and objects which need a whole sentence in other languages to explain. For example, some languages, will have separate verbs for go which distinguish whether the verb means go uphill, downhill, on foot or on horseback and others will have separate nouns to describe the same animals at different stages of their development and usefulness.

|

Schemata |

Schemata (singular schema) are sometimes called frames

or scripts.

The significance is that they activate our encyclopaedic knowledge

through context and that has very obvious implications for the

classroom and the teaching of lexical meaning.

For example, if one considers a simple sentence such as

The glasses were broken

it is likely that, without any other context, most people will have

their schema concerning glass drinking vessels activated.

However, given the context of being able to read a label and the

sentence

My glasses were broken

it is likely that the schema which will now be activated concerns

spectacles.

Given, as another example, the sentence:

The party was united

vs.

The party was noisy

it is likely that wholly different schemata will be activated simply

by the difference in the adjective used to describe party.

Because encyclopaedic knowledge, on which schemata work, is

variable from individual to individual and the core meanings of

words are not easily translated across languages or between

cultures, it becomes very important for teachers to provide adequate

data to allow learners to notice (or be told) what is and is not

included in a concept represented by a lexeme.

At the outset, it may be enough to define, for example, the verb

harvest by reference to well-known examples such as gathering

wheat, rice, vegetables etc. but that may not be enough to

distinguish the word from the idea of pick (as in flowers,

blackberries or other wild fruits) and it almost certainly won't be

enough to allow learners to understand that harvesting data

is possible but picking data has a wholly different

meaning.

Word meaning is learned incrementally with the learners'

understanding of limitations and inclusions in the meaning of a

lexeme being refined as more data become available.

It is, therefore, as important to help learners understand what is

excluded from a word means as it is to convey what is included.

For example, the comparatively simple idea conveyed by the word

steps (which might be explained as a series of flat surfaces on

which to climb up or down) needs to be refined by excluding carpeted

wooden examples inside houses but which will include metal external

fire escapes while probably excluding internal stone fire escapes.

The concept of register (i.e., the field, in Halliday's 1978

analysis) in which a word occurs is critical in this area.

If, for example, we know that we are listening to or participating

in a conversation about a parliamentary debate, we will almost

certainly understand the word minister differently from how

we would understand it if the conversation concerns church

employees.

Little by little, we are now moving from word and sentence

meaning to utterance meaning and here we trespass on the territory

of pragmatics. So be it.

However, before we move on, here's a summary of the story so far:

|

Compositionality |

You will readily see that knowing the senses of the individual

lexemes in a clause or phrase usually allows you access to the overall

meaning. For example, knowing the meaning and/or function of

completely, problem, the, is, clear, me, to

You can arrive at the meaning of the sentence:

The problem is completely clear to me

and

To me, the problem is completely clear

and even

Completely clear to me is the problem

That is what is meant by compositionality.

However, there are many instances of language when knowing the

sense of the constituent parts of a string of words will not allow

you access to the overall meaning. You may, for example, know

the meanings of

family, he, black, of, sheep, the, is

but that will not allow you to understand

He is the black sheep of the family

This is what is meant by non-compositionality. Idioms and

phrasal verbs are familiar examples of non-compositionality but it

is not an either-or distinction. Some idiomatic expressions

can be understood with access to the concept of metaphor and such

items vary in the level of transparency. So, for example

He put the meeting off until Wednesday

is reasonably transparent with an understanding that the particle

off frequently carries the meaning of away from

as in, e.g.:

He took the plate off the table

and

application of the meaning of the prepositional phrase helps, too,

of course. However,

He put up with her

is almost completely obscure unless you are aware of the meaning of

the multi-word verb put up with (=tolerate).

When it comes to idioms, some are often used quite literally and

some can only be understood as metaphors. For example:

She won by a hair's breadth

is an idiom in English which is fixed so you can't change

hair to strand or breadth to width

and retain the same meaning. It is, however, reasonably

transparent in suggesting a narrow margin of victory.

On the other hand, something like:

He made it by the skin of his teeth

is less transparent insofar as teeth do not have skin for one

thing. Indeed,

That doesn't cut the mustard

is almost wholly obscure and must be understood as a single

idea (not good enough).

There are, in other words, various levels of non-compositionality.

For more about this, see

the guide

to idiomaticity, linked at the end, which also covers the notion of fixedness.

|

Use and Usage

|

The distinction here is between sentence meaning and utterance meaning and lies at the heart of communicative language teaching. The distinction can be summarised:

Usage means focusing on the meaning

attached to something as an instance of language isolated from

context. It is its signification

(what it means).

Use refers to the meaning of something when used for communicative

purpose. This is its value (what

it does).

For example:

A: Why don't you see a doctor if you are feeling so ill?

B: Mount Everest is very high and Mercury is the nearest planet to

the sun.

B's statement has significance (we know what is meant) but no value

(it communicates nothing useful).

(Widdowson, 1978)

Utterance meaning can be quite obscure and include attempts at

satire, irony and so on. Two obvious examples are hyperbole

and litotes.

Hyperbole is deliberate exaggeration for effect in, e.g.

There were millions of people at the party

It weighed a ton

when in neither case do we literally mean millions or a

ton.

Litotes is the polar opposite way to get the same effect in, e.g.

You'll find the centre of London a bit busy on Monday mornings

I drove to Greece and back from the UK so I've done a few miles

when in neither case is the downtoner (a bit and a few)

meant literally. The centre of London is actually extremely

busy at this time and there are more than a few miles between Greece

and the UK.

|

Communicative force |

Another way to distinguish between sentence and utterance meaning

is to consider communicative force.

If for example, someone says:

The food is on the table

there are three possible communicative forces in play:

- Locutionary force

- The 'basic' or sentence meaning of what is said.

In our example, this would correspond to the meaning that the food is in the place I have specified. No more, no less.

Another way to say this is that you have understood the propositional content of the utterance. - Illocutionary force

- The meaning intended or the meaning perceived – the

utterance meaning.

In our example, the statement could mean, Please sit down and eat or a number of possible meanings such as It is getting cold. - Perlocutionary force

- This refers to the fact that an utterance like this may actually produce a reaction in the hearer. If, in this example, the hearers immediately come to the table, sit and begin to eat then the perlocutionary force of the statement has been demonstrated. In some instances, the simple utterance results in the effect. For example, I now pronounce you man and wife may result in the marriage with no intervening linguistic form.

The distinction between sentence meaning and utterance meaning is important for language teachers, of course. The distinction is also used to divide semantics proper (i.e., the study of sentence meaning) from pragmatics (i.e., the study of utterance meaning) but the distinction is neither clear cut nor universally accepted.

|

Gricean maxims |

Herbert Paul Grice's work is relevant in the area and to the

teaching of language using any communicative approach. It

bears some analysis here although it is also relevant to other areas

in this site.

If one starts from the premise that utterances have some kind of

illocutionary force, i.e., an intended meaning which the hearer

understands, we need to know something about the principles at work

which allow the meaning to be understood.

Grice's work is not, of course, without its critics so the following

is, at best, the theory, at worst, simply a hypothesis. There

are four main maxims which determine how interactions proceed.

Overriding all four is the Cooperative Principle. In Grice's

words, this is:

Make your contribution such as it is

required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose

or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.

(Grice 1989: 26)

The four maxims we follow to achieve this are:

- THE MAXIM OF QUALITY:

- Don't say what you believe to be false.

- Don't say things for which you have no evidence.

- THE MAXIM OF QUANTITY:

- Be informative enough.

- Don't over-inform.

- THE MAXIM OF RELATION:

- Be relevant.

- THE MAXIM OF MANNER:

- Avoid obscurity.

- Avoid ambiguity.

- Be brief.

- Be orderly.

The issue here is not that we always follow these maxims but that we are subconsciously aware of them. When any are broken, we are immediately alert to the fact that something other than the sentence meaning is intended.

- Example 1:

- If in answer to

What time's dinner?

the response is

But you promised!

Then, on the face of things, the maxim of relevance has been breached because the response is not obviously relevant to the question. However, if the hearer is alert, she/he may presume that the response means something like

I'm not cooking because you promised to do it so you tell me when it'll be ready. - Example 2:

- If the response to:

I'll get myself a beer

is

There's a shop down the road, just by the post-office which sells all kinds of drinks, including beer

Then, on the face of it, the maxim of quantity has been breached because this is just too much information. However, the illocutionary force to which the hearer may be alerted could be

You should go and buy your own beer and not keeping helping yourself to mine. - Example 3:

- If the response to:

Lend me $200

is

Pigs might fly

Then it seems that both the maxim of quality and the maxim of relevance have been broken but the response may simply mean

It is about as likely that I will lend you $200 as pigs flying (i.e., not particularly). - Example 4:

- Jokes are rich sources of maxim breaking precisely because

they rely so often on unexpected responses to utterances.

For example:

I rang the bell of a bed-and breakfast place and a lady appeared at a window.

"What do you want?" she asked.

"I want to stay here," I replied.

"Well, stay there then," she said and closed the window.

which breaks the maxim of quality at least and probably the maxim of relevance by deliberately misunderstanding what is meant by here.

There's a good deal more on Gricean maxims and their classroom implications in the guide to pragmatics on this site.

|

Jokes and breaking maxims |

Here's a joke for you to try. What maxims are being broken?

Click here when you have an answer.

There is a woman

sitting on a park bench and a large dog lying on the ground in front

of the bench. A man comes along and sits down on the bench.

MAN: Does your dog bite?

WOMAN: No.

(The man reaches down to stroke the dog which bites him.)

MAN: Ouch! Hey! I thought you said your dog doesn't bite!

WOMAN: He doesn't. That's not my dog.

The

woman breaks the maxim of quantity because it is clear that the man

is referring to the dog in sight. He has no way of knowing

that she has a different dog and it is natural to assume that the

dog is hers. She has been economical with the truth and

provided too little information.

She is also breaking the maxim of relevance by referring to another

dog which is not present.

The whole joke (if it can be called that) is dependent on breaking

the cooperative principle.

|

Other guides |

The whole area of semantics (and pragmatics) underlies the theory of language which informs almost any teaching approach. The following guides become clearer in the light of semantic theory and reference to this guide.

| Related guides: | |

| suasion | focusing on some key functions in English more easily understood in relation to utterance meaning |

| CLT | the guide to Communicative Language Teaching |

| morphology | focusing on how words are constructed and what their individual parts signify |

| idiomaticity | focusing on (non-)compositionality and notions of fixedness |

| polysemy | focusing on multiple word senses and other relationships such as synonymy and metonymy |

| lexical relationships | focusing on lexical relationships such as hyponymy, troponymy and antonymy |

| collocation | for more on suppositional meaning |

| language, thought and culture | for some considerations of whether language determines thought or whether the reverse is true |

| the evolution of language | a guide which contains consideration of how the arbitrary nature of words and their meanings may have evolved |

| multi-word verbs | focusing on these verbs and also on notions of transparency and derived meaning of particles |

| function words | the guide to help with recognising different levels of meaning |

| deixis | although not central to semantic analysis, notions of reference are applicable to this area |

| pragmatics | this extends many of the considerations of the second half of this guide |

If you would like to take an easy test on all of this, click here.

References:

This is a huge area, much researched and written about. Many

studies of semantics focus on cross-linguistic comparisons,

sometimes of obscure and exotic languages, and are less than helpful

for English language teachers. However:

Aitchison, J, 1987, Words in the Mind: An introduction to the

mental lexicon, Oxford: Blackwell

Grice, HP, 1989, Studies in the Way of Words, Harvard: Harvard

University Press

Halliday, MAK, 1978, Language as a Social Semiotic, London:

Edward Arnold

Reimer, N, 2010, Introducing Semantics, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press is an accessible source.

Schmitt, N, 2000, Vocabulary in Language Teaching,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Widdowson, HG, 1978, Teaching Language as Communication, London:

Oxford University Press is also accessible and to the point.