Morphology: the building blocks of language

This guide is concerned with the general theory of morphology rather than with how any one language forms words by combining morphemes. For more on that, in English, consult the guide to word formation, linked below.

|

What is morphology? |

We'll start this guide with a definition of its subject matter.

A morpheme is

the smallest meaningful unit of a language.

and the word meaningful is emphasised

for a reason.

In this phrase, we have these 10 morphemes:

the + small + est + mean + ing + ful + unit + of + a + language.

The term meaningful here does not refer to meaning standing

alone (although it may) but to meaning in context or in combination

with other words.

For example, a function word such as it carries no meaning

without a context and co-text but in a sentence such as:

I read the book and loved it

the words book and it clearly carry meaning.

And in

John and Mary came to the show

the word and carries a meaning to the hearer / reader

relating to combining subjects although the word standing entirely

alone has no discernible meaning.

Both it and and are morphemes by this definition

and so are I, read, the, book, love, -d, John, Mary, came, to

and show.

Morphology, then, is the study of how languages form words. All languages do this and they do it in a bewildering and fascinating number of ways.

We are concerned here with how English functions in this respect but

effective teaching in this area requires at least an outline

knowledge of how your learners' language(s) function. For some

information about that, see the guide to teaching word formation,

linked below. Other languages employ morphemes in a variety of

ways using, e.g.

infixes: a rare event in English exemplified by spoonsful

or absobloodylutely.

circumfixes: unknown in English but used extensively in some

languages which add affixes in pairs to the beginning and end of a

lexeme to derive a single change in meaning or word class.

The guide to word formation, linked below, covers similar ground but extends it into other areas. This guide is concerned with understanding the theoretical bases for how words are formed in English.

|

Identifying words |

Before we can sensibly look at what words are made of, we need to

be clear about what a word actually is. This may seem a very

simple question but it is actually rather difficult to define what a

word is in any language.

Here's a definition from Google:

a single distinct meaningful element of speech or writing, used with others (or sometimes alone) to form a sentence and typically shown with a space on either side when written or printed

As we shall see, that is not an adequate definition for our purposes. The definition is hedged with typically and sometimes and that is a sign that the definition is difficult.

|

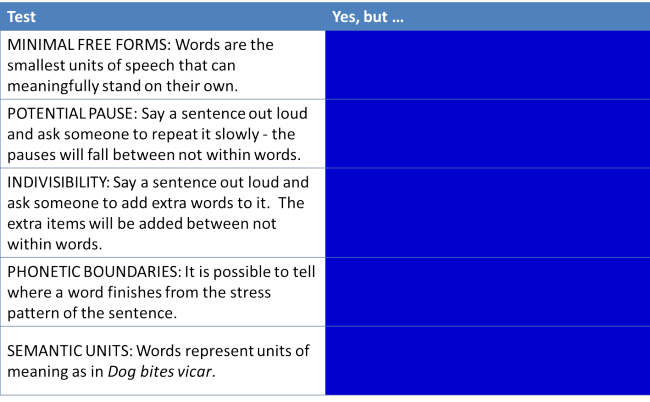

Task 1:

Here are some traditional tests for words in a language. Click on the table when you have filled in the right-hand column. |

(Based on Crystal, 1987:91)

Even the test for words

are things which have a space at each end when they are written down

doesn't work. (Is doesn't one word or two?)

Some languages do not follow the convention at all and all words are

written in a stream. For example,

What will you have

in Thai looks like

สิ่งที่คุณจะต้อง.

It is for these reasons that linguists prefer the term

lexeme or lexical item to the anguished

word word. A lexeme is a basic unit which can be one

word or a phrase which carries a single significance.

By this definition, all of these are lexemes because the individual

parts, where they exist, do not convey the whole meaning:

| house | terraced house | room | living room | classroom | party | the Labour Party |

| America | The USA | scissors | fountain pen | garden | market gardener | omnishambles |

Of course, one ordinary way to identify a word is to look it up

in a dictionary. Unfortunately, that won't work, either.

If you go to an online dictionary for something like

inderivability, you are very unlikely to find it but most

native speakers of English would be happy to accept that it really

is a word.

The other issue with dictionaries is that, in order to save space,

they usually list words by the root or lemma. For example, you

will find repeat as a headword or lemma in a dictionary but

repeated and repeating will normally not be listed

separately unless the words are used with a different significance.

That doesn't mean they aren't words.

So what actually is a word?

For a morphologist, a word is any item which can be derived from

the application of morphological rules. This means that even

something like computerhood, which you will certainly not

find in a dictionary, is a word because it can be derived from the

three morphemes that make it up, following normal conventions in

English. These are:

compute

the verb

+ r to make

the noun doer of the verb (or, with words that do not already end in

'e', 'er')

+ hood

to make the noun signifying state of being a doer of the verb.

|

Identifying morphemes |

|

Task

2:

Can you identify the morphemes in this list of lexemes? Click on the |

| SUGAR |

This is an easy one. The lexeme is a single

morpheme which stands alone. We can add morphemes

to it, of course, to make, e.g., sugary,

sugariness etc.

It is a free morpheme which needs no other morpheme to make sense. |

| CLASSROOM |

This is a compound formed from two

free morphemes, class

and room.

Both are nouns and they combine to make a new noun with

a new but transparent meaning. See

the guide to compounding, linked below,

for more.

|

| UGLINESS |

This is an example of a free morpheme combining with

a bound morpheme to make a new word

class.

We have taken the free morpheme, ugly, and combined it with a bound morpheme suffix, ness, to make the noun from the adjective. The suffix is a bound morpheme which cannot stand alone and carry meaning. Because the morpheme is used to derive a new word, it is called a derivational morpheme. (Do not worry about the spelling change. That is simply one of the orthographic conventions in English and makes no difference to meaning. Do not be concerned, either, with the fact that ness can be a free morpheme meaning a headland. That is an example of homonymy.) |

| TEACHERS |

This is an example of the same thing. A free

morpheme, teach,

combining with a bound morpheme,

er, to make a

personal noun from the verb. In other words, to derive a new word class.

There is a second bound morpheme,

s, which forms the

plural in English, part of how nouns decline.

|

| FLYING |

This, too, is an example of a free morpheme

combining with a bound morpheme (fly

and ing,

respectively) but in this case we have a grammatical

change, converting the base form of the verb into a

participle or a gerund, depending on context.

This is an inflexional morpheme,

determining how verbs conjugate.

|

| REPEATED |

This is slightly problematic. Often, the bound

morpheme prefix re

implies the act of doing something again, as in

rewrite,

reinforce etc.

Here, however, analysing it that way would result in the

morpheme peat

which, as a verb, carries no meaning so cannot, by

definition, be a morpheme in English. It is,

however, acceptable to analyse it that way because the

verb derives from the Latin, via French, from re, [again] + petere

[strive after; ask for]. It occurs again in, e.g.,

petition.

We have another inflexional morpheme here, ed, which forms the regular past tense in English. |

| HAMBURGER |

This, of course, can mean a person from

Hamburg

and that is an example of a free morpheme, called the

root, combining with a bound morpheme

to form the name for a person's origin. Compare

Londoner,

Parisian etc.

In this case, however, the word probably derives from the name of a beef product from Hamburg and the morpheme burger has taken on a life of its own as in cheeseburger, beefburger and veggieburger. |

| DISRESPECT |

The function of the bound morpheme,

dis, as a prefix is

clear; it means the negative. However, hidden in

here is another Latin-derived meaning of

re. The word

derives from re [back] +

specere [look].

|

| BLAIRITE |

This is an example of how new words are formed from

the general rules of a language's morphology. We

simply take the name or philosophy and add

ite or

ist. Compare

Trotskyite, Marxist, communist, sexist, Thatcherite,

Benthamite etc.

|

| REAGANOMICS |

This is a less common way to form new words called a

blend. Two words have been

fused to form a third meaning. Compare smog

[from the free morphemes smoke + fog]

or motel

[from motor + hotel].

|

| DONATION |

You can be excused for thinking that this is a noun

formed from the verb donate by dropping the 'e'

and adding the -tion

bound morpheme in the conventional way. However,

in fact the noun entered the language much earlier than

the verb which was formed later by analogy with more

usually formed verb-noun pairs such as

inflate-inflation and many more.

This is called a back formation and there is a short list in the guide to word formation of other back forms in English. |

| INEPT |

This is interesting because the bound morpheme,

in, clearly carries

a negative meaning. Unfortunately, the second

morpheme, ept,

carries no meaning. The word comes from

Latin in- [not] + aptus [apt].

The term for this kind of morpheme is a bound base (sometimes a bound root). It cannot exist alone but does not act as a prefix or suffix. Other examples are the ver in verity, the doct in doctor and the dext in dexterity. Many verbs are formed in this way, derived directly from Latin, Old French or Old English with a bound base which has no independent existence in the modern language. Examples include desiccate, modify, indemnify, enlighten and more. |

| PESTICIDE BIOCHEMISTRY |

These are examples of combining forms.

The suffix,

-icide does not alter the meaning of the word

pest or its word case (as is the case with, e.g.,

pester). The suffix instead adds a new layer of

meaning to the word and denotes killing agent.

The second example is similar but the combining form (bio-) is a prefix (the more common role of combining forms). Again, it does not alter the meaning of chemistry but it does add a new layer of meaning to it. In these cases, the words pest and chemistry are free morphemes but in many cases of the use of combining forms in English, the base is not a free morpheme. Examples are: democracy, ferroconcrete, astrology. The roots here, dem, ferro and astr do not stand alone and are describable as bound bases which can be traced to the Latin or Greek roots. Combining differs from compounding in that the outcome is not a third meaning, it is an additional meaning grafted on to the base form. |

All the technical terms are in bold

in this table.

Click here to take a test to see if

you can remember what they mean.

|

Derivational morphemes |

As we saw above, there are two ways that derivational morphemes added to lexemes can change them.

- We can change the word class or category of a word but leave

the base meaning unchanged. For example,

- entertain (verb) → entertainment (noun)

- entertain (verb) → entertaining (adjective)

- elephant (noun) → elephantine (adjective)

- We can add morphemes which change the meaning but leave the

word class unchanged. For example,

- pleasant → unpleasant (adjectives, opposites)

- do → undo (verbs, reverse action)

Sometimes, we can add morphemes which change both the meaning and the word class. For example,

- witch (noun for a person) → bewitch (verb meaning enchant)

- list (noun) → enlist (verb meaning put or put oneself on a list of participants)

- garden (verb) → gardener (noun,

verb changing to person who does the action)

This is not the person being derived from the place but the person derived from the verb. We need to be careful to make this sort of thing clear to learners or they may think a shopper is someone who works in a shop.

|

Productivity of derivational morphemes |

A central concern of morphology is to investigate how productive

a derivational morpheme actually is. This does not apply to

inflexional morphemes because their role is generally fixed

grammatically

How is it, for example, that the morpheme

th can be attached to some adjectives to form the

noun (warm → warmth, wide → width

etc.) but is almost completely unproductive in forming new words in

English?

We would not, for example, take the adjective

windy and form a noun such as windith,

preferring instead to choose the ness

suffix and making windiness.

There are some interesting factors in play.

|

Transparency |

Some morphemes have an easy-to-see relationship between the form and meaning. Here are some examples:

- -ible and

-able

It is easy to unpack a word like recordable by considering the suffix able and realising that it always produces an adjective from a transitive base verb and that it exists as a free morpheme meaning can. You can quite easily make new adjectives like this from any number of verbs, providing they take an object. The fact is that it is the only way English can form a new adjective from a verb. We have, of course, the ible morpheme in words like flexible, audible, comprehensible and so on but if you try to form an adjective from unusual or phrasal verbs you will almost always opt for able. Try it with:

prune, devolve, explode, derange, disturb, put off, turn down.

The morpheme ible is, therefore, unproductive.

There are still many extant adjectives formed from verb which employ the -ible suffix. However, removing the suffix does not usually leave a recognisable word so, for example:

audible

risible

incorrigible

etc.

Here, again, we have instances of a bound base or bound root which is no longer able to function alone. The words aud, ris and corr simply do not exist although they can be traced to Latin.

In nearly all cases, the -ible forms are more formal and less common so we have formal-informal pairings such as:

credible - believable

edible - eatable

potable - drinkable

risible - laughable

illegible - unreadable

comprehensible - understandable

etc. - nouns from adjectives

Another example is the ways in English that nouns are formed from adjectives. The two most common are:

ness: happy → happiness, sad → sadness, great → greatness etc.

ity: insane → insanity, absurd → absurdity, acid → acidity etc.

However, if you try to form new nouns from these adjectives:

blue-green, airy, snowy, freezing, wet

You will almost always opt for ness, indicating that ness is more productive than ity in this function.

This is not to say that ity is unproductive in the way that th is, but that it is less productive. It can be very productive with adjectives ending in the able morpheme. Try, e.g.,

openable, disturbable, derivable, pickupable

and -ability seems to be the form of choice although it is certainly possible to form words like openableness. - doers

Other derivational morphemes are also less productive than others. We can, e.g., form the doer of a verb by attaching the morpheme ant as in

inhabit → inhabitant

assail → assailant

claim → claimant

but this suffix is far less frequently used for this function than the ubiquitous er suffix. Try forming the doer of the action from these verbs and you'll see how much more productive the er morpheme is:

disturb, peruse, demand, accommodate

The suffix ist is even less productive in this sense although typist and telephonist exist.

Just as we saw for the able/ible distinction, the suffix or is now almost completely unproductive and is frozen into words like actor, transgressor and doctor. - Nonce words

Speakers of English frequently make up words by the addition of a derivational suffix or a small range of prefixes. We get, therefore words such as:

speakable

screwability

framableness

writingless

misdecide

travelful

unframe

disharmonise

and so on, none of which will appear in a dictionary and all of which are temporary (nonce) introductions. Nonce words are sometimes referred to as occasionalisms. - Barbarisms

This term is used by language purists to describe formations which are disparaged because acceptable and derivationally purer forms already exist. Some will not become popular but many so-called barbarisms have already entered the language. For example:

orientate is a verb formation already covered by the verb orient

preventative is an adjective whose meaning is not distinguishable from preventive

untactful is an unnecessary addition to a language which already contains tactless

educationalist is not clearly distinguishable from the current educationist

metrification does not add anything useful not covered by metrication. In fact, it adds unnecessary suffixes because there is no verb metrify or metrificate but metricate certainly exists.

and so on.

In some cases, these questionable coinages will become the usual forms, in others, they will die out.

As has been pointed out:

Ultimately, it is general usage, rather than etymological pedigree, that determines the survival of a word. (Todd & Hancock 1986:71). (Although they may, of course, mean use rather than usage.) - Combining forms

When an additional meaning is grafted on to a term by the addition of a suffix it does not usually change the word class so cannot be derivational in this sense. The guide to word formation contains more on this area and there is a list of such forms linked below. Words such as

thermometer

heliotropic

Francophone

herbicide

are examples of the use of combining form suffixes which do not change the word class (even if they are appended to recognisable words at all, which many are not).

Combining forms are, especially in academic and scientific writing, very productive indeed so recent formulations, such as anthropocene (the current geological age) are coined at will and retain their existence for many years.

For a much more complete list of the semantic functions of suffixes, see the guide to word formation, linked below.

|

Frequency and usefulness |

Some suffixes are simply too constrained in the number of bases

they can be attached to to make them very productive.

We can make an adverb from some nouns with the suffixes

wise

and wards as in, e.g.,

crabwise, clockwise, northwards, citywards etc.

but the number of possibilities is very limited because of the

infrequency of the resulting adverbs and the small usefulness the

concepts have.

However, the adverb forming ly is hugely productive in its

ability to produce adverbs from adjectives because the results are

both frequent and useful. It can also attach itself to the

barely limited number of participle adjectives in English. So

we can form, for example:

stunningly, interestingly, swingingly, boringly,

understandingly, reassuringly

and so on. We can even make up new adverbs on the spur of the

moment and be understood, for example:

She spoke praisingly.

|

Other constraints |

- phonology

- some morphemes behave along phonological lines. For

example:

The verb forming ize/ise usually attaches to multisyllabic nouns and adjectives if the stress is not on the final syllable. So we get, e.g.:

random → randomize

real → realize

apology → apologize

Another verb-making suffix, en, attaches itself to single syllable adjectives but only if they end in certain phonemes (stops, and fricatives):

deep → deepen

light → lighten

broad → broaden

deaf → deafen

but not

clear → *clearen

high → *highen

in fact, we insert a 't' to conform with the phonological rule and get heighten.

This applies to prefixes, too, as we see with the choice often of im rather than in before /m/ and /p/ and ir before /r/. - etymology

- The root of a word will often determine what derivational morpheme is possible.

- For example, the adjective-forming suffix

ic will not attach to

Anglo-Saxon bases but en

will so we get:

vitriolic, metallic, dramatic

but

woollen, leaden, ashen - meaning

- The prefixes un, im, in

etc. do not attach to words with negative connotations so we

can't have:

*unvile, *impernicious, *undoleful, *unhelpless

etc. but we can have

unlovely, unappreciated, improper, unhelpful

etc.

Derivational morphemes are dealt with in greater detail in the guide to word formation, linked below.

|

Teaching implications of productivity and other constraints |

|

Task

3:

Review the sections above on aspects of productivity and the

constraints on word formation with derivational morphemes

and consider for a moment what the implications are for

teaching English. Consider, too, production vs.

comprehension. Then click here. |

- transparency

- When introducing the concepts of word formation in English,

it makes sense to start with those morphemes whose meaning is the

most transparent. They also tend to be the most

productive, of course, and therefore, the most useful.

So, start with simple affixes which have a near one-to-one relationship between form and meaning:

Suffixes like: able, ness, ity, ize/ise are good candidates.

Prefixes such as un, re, pre are also good candidates. - frequency and usefulness

- are considerations to bear in mind when deciding

on the teaching of any lexis and it is sensible to exclude

noun-making suffixes such as th

and adjective-forming suffixes such as

esque because they are either wholly or nearly

fully unproductive in English. In fact, singling out

th as a noun-former at

all is probably a waste of time. Learners do not need to

know that the noun width is formed from the adjective +

the suffix because the suffix itself is no longer productive.

It makes more sense to focus on:

Noun-forming suffixes like ness, er, ity, eer, ist rather than ant, dom, ery, hood etc.

Adjective-forming suffixes like able, less, ful, ish, ist rather than ous, ic, ian.

The adverb-forming ly rather than wards or wise.

The verb-forming ise/ize rather than fy, en. - constraints

- Phonology and meaning are the two to focus on because

etymology will only be useful in real time for learners with a

narrow range of European first languages.

It is, for example, predictable from the syllable number and stress pattern (two syllables or more, stress not at the end) that the verbs from

computer, brutal, central, economy, familiar, national, personal

etc. will all end in -ize or -ise.

The constraints on the use of en in this function are much less easily applied but phonologically, for example, deriving quieten from quiet is not too challenging once you spot the /t/ ending and from there, it is a short step to forming tighten, flatten etc.

The fact that already-negative adjectives (like ugly, vile, hateful, odious, helpless, antagonistic) do not take antonym-making prefixes but positive ones (such as kind, comfortable, generous, helpful, likeable) do is easy to grasp and the knowledge will help learners avoid a good deal of potential error. - comprehension vs. production

- Armed with a knowledge of the function of common affixes,

learners can significantly increase their receptive lexicon.

Production is harder, of course, but opting for the most productive affixes when speculating on word formation will usually pay dividends. If you want to make the opposites of these adjectives, what would you choose?

cut, read, quiet, easy, lived-in, organised, classified, worried

Participle adjectives very frequently form their opposites with the simple un.

Nouns formed from adjectives are overwhelmingly made with ness (and less frequently ity) so that's the way to bet if you want to form nouns from adjectives from, e.g.,

delightful, malicious, rocky, thrifty, dark, clever

then the natural selection is ness and you'll be right nearly all the time.

If the adjective ends in able, opt for ity:

readable, drinkable, editable, pronounceable, describable etc.

|

Inflexional morphemes |

In English we can denote a number of grammatical constructions by

using inflexional morphemes. We usually do this by changing

the ending but, irregularly, we can also change the internal

characteristic of the lexeme (a process called mutation or ablaut

when it affects the vowel). Inflexional morphemes always, in

English, follow derivational morphemes. We get, therefore,

e.g.:

nation+al+ise+d

not

nation+al+d+ise

Inflexional morphemes include:

- Tense:

We saw above that the -ed/-d morpheme signals past tense but it also signals a past participle for regular verbs:

talk → talked

hope → hoped

and for some irregular verbs the past participle is also marked by a morpheme addition

forgot → forgotten

broke → broken

Internal changes (mutations) are also morphemic but what usually occurs is that one bound morpheme is altered and becomes a slightly different bound morpheme as in, e.g.

understand → understood

behold → beheld

English is unusual among European languages in having only one past-tense form to apply to all persons. Most other languages in this family use different endings for most of the persons and number.

It is also unusual in often having the same form for the past tense and the past participle. Other languages, such as Greek, distinguish the forms. - Aspect:

English signals progressive and other aspects by changes to the verb:

go, going, gone

Again, English is very limited in this respect having only one form of the past participle and only one of the -ing form. The -ing form, incidentally, has no irregularities. None. - Person:

Apart from the truly irregular verb be, English only signals person with the third-person -s morpheme (and then only in the singular):

speak → speaks

hang → hangs

By European language standards, this is a very limited range. In some other European languages, for example, the translation works like this:

This is not universal and, for example, all three Scandinavian languages (Norwegian, Swedish and Danish) have the same form for all the verbs in all persons (går).English French German Polish Estonian Italian I go

you go

she goes

we go

they goje vais

tu vas

elle va

nous allons

ils vontich gehe

du gehst / Sie gehen

sie geht

wir gehen

sie gehenidę

ty idź

ona idzie

idziemy

idąma lähen

sa lähed

ta läheb

me läheme

nad lähevadio vado

tu vai

lei va

andiamo

vanno

For this reason, many languages, such as Greek and Italian, routinely drop the pronoun because the person is signalled by the verb ending. The term for these languages is pro-drop incidentally, and there is more on that in the guide to types of languages, linked below. - Number:

Although there are some irregularities, English uses the s/es morpheme to signal the plural.

class → classes

house → houses

Almost all nouns function this way in English which is a simple system in comparison to many other languages (and more complex than many which do not signal the difference between singular and plural at all). - Adjectives:

English uses morphemic addition to change some adjectives from absolute to comparative or superlative:

long → longer

small → smallest

The morpheme most can also act as a suffix carrying a similar meaning of towards the extreme in words like nethermost, uppermost, hindmost etc. The morpheme more can't do that and the suffix most is now unproductive.

The added complication in English is that some adjectives cannot take the inflexion at all so we do not allow, e.g., boredest or beautifuller. The rules for when we inflect and when we use the periphrastic form are quite complex, in fact.

Other languages are often simpler in this respect. Most Romance languages, French, Spanish, Romanian, Portuguese etc. employ the periphrastic form and some, such as German, usually employ only the inflected form (although the periphrastic form is available), others, Scandinavian languages and some Slavic languages, for example, work a little like English.

Adjectives in English remain unchanged, whatever case, gender and number they are associated with. Other languages will often inflect the adjective to show case, gender and number. - Case:

Many languages, which take advantage of morphemes to signal case (nominative, accusative, dative, genitive, locative, ergative etc.) alter the nouns and other elements to show this. English generally does not do this with content words but has a slightly complex pronoun and determiner system which sometimes radically alters a morpheme to show case and sometimes simply adjusts it slightly:

and so on. A full list is available in the guide to personal pronouns.Nominative (subject) Accusative (object) Genitive (possessive) Genitive pronoun I

you

she

he

they

whome

you

her

him

them

whommy

your

her

his

their

whosemine

yours

hers

his

theirs

English also deploys the 's morpheme for the genitive:

John's, the dog's, the ship's, the government's

The fact that English has two genitive structures (the government's policy vs. the policy of the government, for example) is an added complication which leads to a good deal of unnatural language in learners and some error.

The technical term for the way in which words can have their grammatical function altered by changes to the morphology is accidence, incidentally.

Old English had many more (and much more complex) inflexions than Modern

English has retained. The loss of inflexion is one of the

most important changes to have occurred in the language. (As a

matter of simple interest, Old English was made even more

complicated by having a separate category for two people. So

we had ic (I), we (we) and

wit (we two) for example and these changed in the

accusative, dative and genitive, rather like modern German pronouns

alter.)

Many other languages, such as German, Polish, Finnish, and French

deploy a much wider range of suffixes to denote number, person, case

and gender. Other languages, such as the Chinese languages are

even more limited than English in their use of inflexions and suffixation.

|

Suppletion

|

Occasionally, we come across a form which is clearly not derived

from what we would expect. For example, the words larger

and largest are clearly connected to and derived from the

base form large but that is not the case with the words

worse and worst acting as the comparative and

superlative forms of the word bad.

What we are dealing with is suppletion and the result is called a

suppletive form. It refers to the fact that the forms are

phonemically and (sometimes) etymologically distinct. The

origin of the word bad is somewhat obscure but the words

worse and worst are traceable to Old English

forms.

Suppletion may be complete as in the example of bad-worse

in which the words share no letters or sounds at all or it may be

quite weak as in the case of five-fifth where the words are

derived from the same root but the pronunciation has been altered so

that the spoken forms may not be recognised as connected at all.

Other common examples of suppletion in English are:

- go, went gone

- The past tense of this verb is clearly unconnected from the

base form and the past participle. The latter two come

from the Old English gan and there are cognates in most

Germanic languages, gehen in German, gaan in

Dutch and so on.

The past tense of the verb, however, is derived from the irregular past tense of the verb wend and that verb has now taken on the regular past tense forms. - three, third

- This is a weaker example because some letters and sounds are shared but hearing the words will not obviously alert people to their connection.

- one, first; two, second

- are both examples of much stronger suppletion because the word first derives from a different root from the word one (although both are traceable to Old English) and the word second is an import via French from Latin and not connected with the numeral two at all.

- far, further, farther, furthest, farthest

- are all examples of quite weak suppletion because they all derive from the same Old English root.

- be, am, is, are, was, were

- is an example of really complex suppletion. The roots are traceable but all come from a different set of words in Old English and Proto-Indo European. It is a tangle of semantically connected forms with no discernible spelling and pronunciation commonalities. The word be derives from the Old English beon (exist), the word am from eom, the word are from the plural form of beon and so on. The past tenses are traceable to the verb wesan (meaning remain). The verb has eight distinct parts in Modern English derived from at least two Old English dialects: be, am, is, are, was, were, being, been.

- good, better, best

- The first of these is traceable to Old English gōd but the two other forms come from a different source (Old English beste).

- person, people

- The first of these derives from the Old French persone and the latter from Old French peupel (itself from Latin populus). The plural persons is rare and formal.

- cow, cattle

- derive from separate roots but the latter is considered a plural collective version of the former. Other forms such as ox-oxen are referred to as suppletive affixes because they do not follow the normal morphological rules for making plurals.

- wreak, wrought

- This is a real oddity because wrought was originally the past tense of work (which is now regular in English). It still exists as a participle adjective in, e.g., wrought iron. The past forms of wreak are in principle regular (wreaked, wreaked) but it has become common to see wrought used as the past of that verb, perhaps by analogy to teach and seek.

|

Prefixation |

For a much more detailed look at prefixes and what they do, see

the guide to word formation. Here, we will simply list some of

the categories into which prefixes fall and the sorts of things the

morphemes do. Nearly all prefixes are bound morphemes.

Free morphemes which may look like prefixes are usually cases of

compounding so, for example, the morpheme house in

housemaster is not considered here as an example of prefixing.

See the guide to compounding for more on that, linked below.

Prefixes come in three main sorts of which the second is the most

productive by far:

- derivational prefixes

are quite rare in English and almost wholly unproductive. In earlier forms of English they were very productive and many modern words such as become, aforesaid, embolden etc. can be traced to earlier prefixation.

They include, e.g.,- en-, em- or im- forming verbs as in:

envisage

enslave

embrace

embroil

imprison - a- forming adjectives such as

ablaze

amaze

asleep - be- forming verbs such as

bewitch

bemire

bedevil

besmirch

- en-, em- or im- forming verbs as in:

- meaning-converting prefixes

which alter the meaning, but not word class of many words.

A full(er) list is available from the link below and in the guide to word formation. The list includes terms denoting:- attitude: pseudoscience, dysfunctional etc.

- negative senses: unbalanced, disbelieve, irresponsible, misuse etc.

- number: monoglot, bipedal etc.

- reversal: undo, decouple etc.

- location: submarine, superstructure etc.

- temporal: prewar, proto-language etc.

- degree or size: supermarket, overdone etc.

- combining forms

which add a layer of meaning without change the meaning of the base. These include many scientific forms such as

biochemistry

hydroelectric

petrochemical

Some words consist purely of combining forms with two bound morphemes. Examples include

democrat

xenophobe

petrology

| Related guides | |

| semantics | for more on meaning |

| types of languages | for a guide to how other languages do things differently |

| prefixes and suffixes | a PDF-formatted list of prefixes and suffixes in English |

| combining forms | a PDF formatted list of the most common combining forms in English |

| compounding | for how this type of morpheme manipulation works |

| word formation | for more on how morphemes combine in English with links to PDF lists of affixes and consideration of combining forms |

| teaching word formation | for a guide containing some consideration of how major language groups handle affixation and compounding |

References:

There's rather a lot in this area which is a much-researched field

and much of it is not relevant to teaching.

Crystal, D, 1987, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Lieber, R, 2009, Introducing Morphology, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Todd, L & Hancock, I, 1986, International English Usage,

Beckenham: Croom Helm