Compounding

If you have followed the guide

to word formation, you will be aware

that English makes new words in a variety of imaginative ways.

Compounding is one of them.

Here are some examples:

| candlestick | noun + noun |

| mouse-click | noun + verb |

| blackboard | adjective + noun |

| heartbeat | noun + verb |

| farfetched | adverb + participle (-ed) |

| oceangoing | noun + participle (-ing) |

| windmill | noun + noun |

All of these example are written as one word but that is not necessarily true of all compounds. For example:

| whisky distillery | noun + noun |

| bee-sting | noun + verb |

| past tense | adjective + noun |

| firing squad | participle (-ing) + noun |

| quick frozen | adjective + participle (-ed) |

| sea-green | noun + adjective |

| washing machine | noun + noun |

|

The problem of definition |

There is no one formal criterion that can be

used for a general definition of compounds in English

(Quirk et al, 1972:1019)

And that is our problem.

Many nouns, as we shall see, can be pre-modified by other nouns

without necessarily forming what many would regard as a compound

noun. However, constant use of such formulations sees the

stress moving to the first element and forming the only stressed

syllable in the expression (a signal characteristic, if not a

defining one, of compound words).

For example, it is clear that the following result in compound

nouns:

a chair with arms = an armchair

a hanger for a coat = a coat hanger

a story about love = a love story

a meeting of a committee = a committee

meeting

and in all these cases, there is one stressed syllable only and it

falls in the first element of the compound (not necessarily the

first syllable, of course, as we see in the last example, but that is usually the way).

In other cases, the situation is much less clear and it is a matter

of choice whether certain combinations may be considered compounds

proper or just nouns pre-modified by other items. For example:

a board to select a candidate = a selection

board

a person who is both an actor and a director = an

actor-director

and in the first case, the stress falls on the second syllable of

the first item and in the second case on the second syllable of the

second item but it is not clear whether both or neither should be

considered as compounds.

|

A single sense |

| wine glass, wine-glass or wineglass |

Compounds, whether written as one word, hyphenated or as two words, represent a single sense.

They form discrete single-sense units and are treated as single lexemes grammatically. In this guide, some compounds are written as two words, some as one word and some are hyphenated. In many cases, it is the personal preference of the writer how such words are written and dictionaries often differ. You may be in the majority choosing to write teacup as one word but coffee cup as two. The senses and the way the compounds are used are parallel regardless of how you write them.

|

Hyphenation and single words |

A further little wrinkle is that one person's compound is another person's double adjective and all double adjectives need a hyphen (we write the wine-dark sea, not the wine dark sea and the brick-built house, not the brick built house).

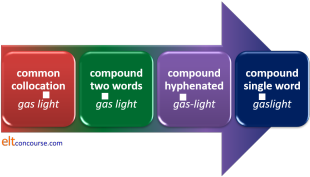

There is also some indication of a cline in the language as a concept becomes increasingly common and conceptualised as a single idea, for example:

When gas for domestic lighting was first introduced, it was a noun-noun collocation

with gas acting adjectivally (as a classifier or noun adjunct), but gradually, as the system became more

common, the term changed until it is now considered a single compound

lexeme.

So, initially, the stress fell on the word light (as the small

white square shows), then it moved

to the word gas, then the hyphenated form became common and

finally the one-word form of the compound became conventional as it now

is in gaslight (/ˈɡæs.laɪt/).

The same stress movement can be observed with terms such as compact

disc which, when first introduced, had the stress on disc

(because compact was an adjective, stressed on its second

syllable) but which is now a compound, stressed on the first syllable of

compact, like this: /ˈkɒm.pækt dɪsk/ not

/kəm.ˈpækt dɪsk/.

It is possible, of course, that a reverse process may occur and, because gas lighting is now uncommon, that over time the stress will move again to the second element and the word gas will function again as a classifier rather than part of a compound.

A recent example you are familiar with is the term mouseclick (a noun-verb compound making a noun) which appears to have entered the language quite rapidly. Each revision of standard dictionaries includes new compounds.

|

Pronunciation: stress |

Nearly all true compounds are given a

main stress on the first element and a secondary stress (if any is

present) on the second

element so we have, from the list above, e.g.:

candlestick:

/ˈkændl.stɪk/

blackboard:

/ˈblæk.bɔːd/

firing

squad: /ˈfaɪər.ɪŋ skwɒd/

etc.

What this means is that the word which determines meaning and word class

is, in fact, usually unstressed in a compound and that runs slightly

counter to people's general intuition because we usually expect

significant meaning-carrying items to carry heavier stress than others.

When we say:

My office has a green door

for example, we would expect the stress to fall on the nouns because

they are the most significant items and so it does. We get:

/maɪ.ˈɒf.ɪs.həz.ə.ɡriːn.ˈdɔː/

with the two main stresses falling on the first syllable of office

and on door.

However, there is also a word greenroom which refers to the

place where actors go when they are not on stage in the theatre and that

is a true compound so the pronunciation of:

My office is next to the greenroom

is:

/maɪ.ˈɒf.ɪs.ɪz.nekst.tə.ðə.ˈɡriːn.ruːm/

in which we still have a main stress on the first syllable of office

but the second stress in the clause now falls on the first syllable of

greenroom as the transcription shows.

(It is also noticeable that the origin of the word is reference to the

colour it was usually decorated in and in the 18th century, it was

written as two words, in the 19th with a hyphen and today it is a single

word. It is a fair bet that it was also pronounced as

/ɡriːn.ˈruːm/ when the expression was

first used. Today's greenrooms are, incidentally, all sorts of

colours.)

For more on how compounds and other words are stressed, see the guide to word stress, linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Plurals |

The other obvious characteristic of compounds is that when they

are plural, the plural marker usually falls on the second element so we get,

e.g.:

beach huts not *beaches hut

child minders not *children minder

desk drawers not *desks drawer

In a lot of cases, of course, the first element is a mass noun

which can take no plural so this makes good sense and we find:

water works

sugar lumps

water board

etc.

Some noun classifiers are, however, irregularly marked for

number. We can have:

a saloon car

but

a sports car

a sports bag

but

a camera bag

a complaint form

but

a complaints department

and so on.

The way to bet is that they are singular so we have

model car collection

portrait gallery

landscape photography

and so on.

Learners who do not have parallel structures in their first

languages will often be tempted to make all noun classifiers plural.

|

Three writing choices |

There are three ways to write compounds and much will depend on the variety of English you use, the commonness of the compound and personal choice. The three choices are:

- Solid, as one word

For example:

bedroom

paperweight

loudspeaker

bookkeeper - Hyphenated (as all double adjectives must be)

For example:

tree-felling

window-ledge

lawn-mower

paper-clip - Open, as two words

For example:

police officer

printing paper

living room

cellar bar

It is likely that anyone reading this will not agree with the list above in its entirety. Dictionaries and spell-checkers will disagree. There is no hard-and-fast rule.

|

Headedness |

In English, the second part of the compound usually determines two things:

- The word class

walking stick is a noun not a verb

software is a noun not an adjective

tailor-made is a participle adjective not a noun - The meaning

windmill is a type of mill not a type of wind

bus driver is a type of driver not a type of bus

police woman is a type of woman not a type of police

The nature of English also requires the right-hand element to take

any inflexion so a plural of a compound noun such as:

bank book

will fall on book, not on bank.

By the same token, any verbal inflexion for tense, aspect or derivation

will only occur if the right-hand element is a verb so we get, e.g.:

sleep walker

homemade

baby sitting

chain smokes

etc.

For this reason, English compounding is described as right-headed. The headword in the compound lies to the right. Many related, especially Germanic, languages follow the same pattern of right-headedness as does, e.g., Turkish.

Other languages do things differently.

In left-headed languages someone who drives a taxi is not a taxi

chauffeur but a chauffeur de taxi (French). In

French, a postage stamp is a timbre-poste, in Polish a

znaczek pocztowy and in Romanian a timbru poștal (stamp

postage in all cases). Other left-headed languages include

Vietnamese, Thai and Welsh.

As we would expect, inflexions for plurality affect the left-hand

element in such languages so the plural of taxi driver in

French is chauffeurs de taxi.

(This applies even to languages which usually have an adjective-noun

ordering so, for example, in Polish, the adjective precedes the noun but

the classifier follows it and

an expensive postage stamp

translates as

drogi znaczek pocztowy)

Many languages avoid compounding and will use a kind of genitive structure (a driver of buses, a stamp of postage etc.) or simply supply a different ending for someone who does something (as English can with gardener, teacher etc.) but, instead of deriving the person from the verb, they will derive the person from the noun and have taxista (Spanish) or tassista (Italian).

Headedness is an issue which can be handled with comparative language work but to be able to do that well, you need to be aware of the characteristic(s) of your learners' language(s). Headedness applies to more than compounds of course but the forms are parallel.To help:

| Right-headed | Left-headed |

|

English and most Germanic languages Scandinavian languages Japanese, Korean, Mandarin and Cantonese Turkish, Basque Most Indian languages |

Romance

languages (French, Italian, Spanish etc.) Slavic languages and Albanian South-East Asian languages (Thai, Burmese, Vietnamese etc.) Celtic languages Most African languages |

|

Transparency |

Knowing that English is right-headed allows one to infer the meanings of many compound word because, e.g., it is clear that a doorman is a type of man, not a type of door and an ashcan is a type of can not a type of ash. This is true for thousands of compounds so simply alerting learners to the headedness of English is a worthwhile 5 minutes of classroom time.

There are times, however, when the meaning of a morpheme in a compound is not readily evident. There are, in other words, levels of transparency which we can assign to the morphemes making up the compound. For example:

- notebook

is wholly transparent: it is clearly a type of book (headedness tells us that) and in it one will find or make a note. That's a case of both parts being transparent. - passbook

is not completely transparent. It is, of course, a type of book, but the relationship and meaning of the morpheme pass is, in this case, not transparent and cannot easily be inferred.

A word such as sketchbook falls into category 1. because it is clear that it is a book containing sketches but the word cookbook is not analysable in the same way because it does not contain cooks.

A compound such as snowman, exhibits a similar problem when compared, for example, to dustman. The latter is a man who collects dust or rubbish and is, again, only partially transparent because one needs to equate dust and rubbish. The former is, however, not someone who collects, or brings, snow, it is a man made of snow. A doorman, on the other hand, is not a man made from a door. - drug-pushing

exhibits a reverse phenomenon. This is clearly connected to the meaning of drug (in illicit narcotic) but it is not clear what the pushing refers to. Understanding right-headedness will not help much here although we can infer that it refers to a type of pushing, not a type of drug. - ladybird

This is an example of doubly opaque compound because it is neither a bird nor connected particularly to ladies. The word exhibits, in the jargon, full non-compositionality and its meaning cannot be arrived at by understanding the meanings of the constituent parts.

The term gatecrasher exhibits a similar phenomenon because it has little to do with gates or crashing but describes an uninvited guest.

|

Types of compounds |

There are three to consider – compounds acting as nouns,

compounds acting as adjectives or adverbs and compounds acting as

verbs.

Within these categories there is, however, a good deal of diversity.

|

Noun compounds |

| handshake |

There are three main types of these which differ structurally. It is worth analysing them carefully because it makes a good deal of sense to focus separately in the classroom on the different structures and word-class elements.

|

Verb + Noun (or Noun + Verb) |

There are two fundamental types of these. Can you see the difference between the following pairs? Click here when you have.

| Type 1 | Type 2 |

| earthquake | dressmaking |

| washing machine | DVD-player |

| earache | window cleaner |

All of these are noun + verb or verb + noun compounds but ...

Type 1 compounds are subject + verb –

the earth quakes, the machine washes

and the ear aches.

There are three distinct types of Subject + Verb compounds:

-

subject

noun + base form of the verb

For example:

landslide, earache, toothache, sunrise, frostbite, rainfall etc.

This is a very productive group and native speakers are apt to make them up as the need arises. The last two of these exhibit some non-compositionality insofar as the terms bite and fall are opaque. -

base form of the

verb +

subject noun

For example:

driftwood, watchdog, watchmen, flashlight, tugboat, searchlight, hangman etc.

This is a far less productive group but all these examples are fully transparent. -

verb in -ing + subject noun

For example:

firing squad, working group, cleaning fluid, sticking plaster etc.

This is a moderately productive group and generally transparent in meaning although a term such as rolling tobacco is less so and would fall into transparency group 2. above.

There is a temptation, succumbed to by some website writers out here, to group all -ing form participles and nouns as compound nouns. This is not the case because:- We should be careful to distinguish between -ing

participles acting as simple adjectives and those forming real

compound nouns. For example,

dancing shoes

is a compound noun referring to shoes used for dancing and does not imply that the shoes are doing the dancing whereas,

boiling water

is water which is boiling, not water used for boiling.

The distinction is usually recognisable in the stress with compound nouns being stressed on the first element and combinations of -ing adjectives and nouns being stressed on the second element. - The other tell-tale characteristic of true compounds

vs. classified or modified nouns is the sense of a

permanent condition. For example:

a barking dog

is a dog which happens to be currently making a noise whereas:

a hunting dog

is a breed of dog used for hunting and the dog in question may be currently asleep in the sun.

Equally:

an opening door

is a door which is currently opening but

a sliding door

is a compound referring to a type of door which can slide (but is probably static at the time of talking about it).

- We should be careful to distinguish between -ing

participles acting as simple adjectives and those forming real

compound nouns. For example,

Type 2 compounds are object + verb –

the dress is made, the DVD is played and the window is cleaned.

Whether the noun precedes or follows the verb is somewhat unpredictable.

The most common way is noun first because of the nature

of right-headedness.

There are distinct groups of these, too:

- object noun + base form of the verb

For example:

haircut, handshake, tax cut, self-control etc.

This is a moderately productive category. - object noun + verb in

-ing

For example:

town planning, storytelling, brainwashing, air-conditioning etc.

This is a productive group. - object + verb + -er (i.e., the

doer)

For example:

fashion designer, songwriter, gatecrasher, window cleaner etc.

Some consider these to be noun + noun compounds and that's a point of view.

This is a productive group and native speakers are apt to make them up as the need arises. - base form of the verb + object noun

For example:

pushbutton, mincemeat, scarecrow, cutpurse etc.

This is a rarer group. - verb in -ing + object noun

For example:

cooking apple, reading exercises, parking meter etc.

Native speakers are, again, apt to make these up as they go along. - verb in -ed / -en + object noun

This is a rarer group in which the compound represents the finished state of something rather than the action performed on it. Usually, these can be alternatively analysed as classifiers + nouns and not true compounds because the stress frequently falls on the second element. However, we can find, for example:

left luggage, cut glass, spoken / written word, stolen property

which are single concepts and may be stressed on the first element.

As we saw above, to be considered compounds at all such items need to represent a permanent rather than temporary state so, for example:

fallen tree, stolen car, lost child

and so on are not compounds but phrases containing participle adjectives describing the current, not permanent, condition of a noun. Temporary state expressions like these are generally stressed on the noun.

|

Verb + Adverbial and Verb + Noun |

These are often lumped together with the verb + noun compounds we have just looked at but there is a distinction:

- In verb + noun compounds proper, the

noun is either the subject or the object of the verb as we have

just seen so:

- When the noun is the subject, for example:

In rainfall, the compound can be expanded to have rain falls (subject noun + verb)

In turntable, the compound can be expanded to the table turns (verb + subject noun) - When the noun is the object, for

example:

In film review, the compound can be expanded to review a film (verb + object noun)

In handshake, the compound can be expanded to shake a hand (object noun + verb)

- When the noun is the subject, for example:

- In verb + adverbial compounds, the

noun is not the subject or the object of the verb but the

compounds tell us where, when or what with the verb is intended.

In other words, the compound is adverbial in nature. So:

- Where:

In waiting room, the room is not the object or subject of the verb wait, the compound tells us where the waiting takes place and can be expanded with a prepositional phrase to get wait in a room. Other examples include hiding place (hide in a place), writing desk (write at a desk) and so on. - When:

In daydream, the noun day is not the subject or object of the verb dream and the compound can be expanded to get dream in the day. - What with:

In handwriting, the noun hand is not the subject or object of the verb write and the compound can be expanded to write by hand.

- Where:

Many of these verb + adverbial compounds use a verb participle with

-ing + a noun. There

are hundreds:

printing paper, walking stick, babysitting,

sunbathing etc.

The verb may follow or

precede the noun but headedness applies so we know that walking

stick is a type of stick and that sunbathing

is a type of bathing.

Other forms use the base of the verb plus a noun (again, following

or preceding):

flashlight, daydream, homework, plaything

etc.

Most of these are countable but homework is not.

|

Compounds without verbs |

Almost all of these are noun + noun: oil well, sawdust, painkiller,

ashtray, fire engine, shirtsleeve, motorbike, headlamp etc.

For teaching purposes, it's useful to note the large group of

compounds using containers:

matchbox, milk bottle, teacup,

coffee cup, cigarette packet etc.

and to help learners notice

that the formation with of changes the meaning:

a

teacup vs. a cup of tea

etc.

Some are adjective + noun: handyman, whiteboard, softball, hardboard, smart-board, wet room, cold room, shortstop, close fielder etc.

In most cases, the right-hand word determines meaning and word class:

printing paper is a kind of paper not a kind of printing, a

tax cut is a type of cut, not a type of tax and so on.

and babysitting is a verb (or a noun derived from the verb) and

plaything is a noun not a verb.

One oddity to note for teaching purposes concerns nouns which are

always plural or which have a significantly different meaning when

used in the singular or plural forms (also called paired nouns and pluralia

tantum respectively). Examples are:

scissors

trousers

arms (weaponry)

and so on.

When these words form part of verbless, noun + noun, compounds, they

are often (not always) made singular so we get, e.g.:

trouser press

scissor sharpener

but

arms race

|

Adjective and adverb compounds |

| ocean-going liner |

As with noun compounds, these are often formed with an object

+ verb. For example, in

a breathtaking view

the breath is taken and in:

a firefighting

crew

the fire is fought

etc.

Other adjectives can be formed as follows:

- Adverbial + Verb

backsliding, homecoming, easy listening etc. - Noun + Adjective

homesick, travel weary, tax-free, battleship grey etc. - Adjective + Adjective

bittersweet, Franco-British, grey-green etc.

The first part of such compounds can contain a derived adjective which cannot usually stand alone.

See the guide to adjectives for a lot more on compounding to form adjectives. There are over ten ways in which this is done and they are set out in that guide.

Again, headedness means that the right-hand word determines

meaning and word class of the first two categories.

Compounded adjectives, on the other hand sometimes imply a

combination of characteristics rather than depending solely

on the right-hand element for their meaning.

sky-blue, lemon-yellow

are respectively a type of blue and a type of yellow and both are right headed

(or head final) in the normal way but

Russo-Japanese

refers to a combination of elements that are Russian and Japanese,

not just Japanese.

Compound adverbs are much rarer than compound adjectives because

an adverb form is uncommonly derivable from such adjectives.

They do exist, however, so we may encounter:

A breathtakingly beautiful sunset

A heart-stoppingly exciting film

and so on.

There is a range of adverbs now written as one word which qualify as

compound adverbs however and the list includes words such as:

thereafter, hitherto, therefore, thereby, overnight, sometimes

and a few others.

They began their careers in the language as two words usually but,

over time have been compounded and are now written as single words.

|

Verb compounds |

| to sightsee |

Verb compounds like sightsee

are often back formations from the noun

compound (in this case sightseeing).

There are two patterns:

- object noun + verb

For example:

lip-read, flat-hunt, pen push, clock watch

In these compounds the first element is a noun which is the object, not the subject, of the verb. - noun + verb

For example

sleepwalk, chain smoke, window-shop, spring clean

These compounds are adverbial in nature because they refer not to the object of the verb but to how, when or where it occurs so we can expand them with prepositional phrases to:

walk in your sleep, smoke in a chain, shop by looking in the window, clean in the spring.

Headedness is again apparent and the second element determines

that the compound is a verb and it is the verb which carries the

central meaning.

This also means that any other word derived from such compounds is

formed by changes to the second element so we get, e.g.:

sleepwalking

window shopper

etc.

And grammatical inflexions will also affect the right-hand element

so we get:

sleepwalked

spring cleans

etc.

|

Bahuvrihi compounds |

| much rice |

This expression is derived from the Sanskrit word meaning

much rice and in that language, it means a rich person.

The defining characteristic is that the compound so formed names an

entire entity by specifying a feature of it. A rich person

owns a lot of rice.

English makes use of this form of compounding usually by referring

to a particular characteristic of the entity and the result can be a

noun (usually) or an adjective / classifier (more rarely).

Here are some examples:

bluebell (with a flower like a blue bell)

loudmouth (with a mouth which is loud)

blockhead (with a head like a block)

paperback (with a paper back)

etc.

|

Classifiers |

As we noted at the outset, there is a very fuzzy border between compound nouns and classified

nouns. There is a guide to classifiers, partitives and group nouns on this site, linked in the list below to which you should refer for more

information.

Briefly, a classifier, or noun adjunct in some analyses, is distinguished from an adjective by being

incapable of modification so, for example, while we can have:

an excellent student

the most excellent student

a really excellent

student

etc.

we cannot have

*a most university student

*a really university student

and so

on.

The word excellent is an adjective describing

a characteristic of the student but the word university is a

classifier which categorises the student.

It is easy to see that it is a short step from classifier + noun to true

compound nouns. Many of the examples cited above could equally

well be analysed as a classifier plus a noun so we would have, e.g.

town planning

lesson planning

route planning

garden planning

etc.

all analysable either as compounding or as classifier + noun structures.

Individual speakers will reveal how they are using some of these

expressions by where they choose to let the main stress fall. If

the speaker is considering the term as a single-sense compound, the

first item will get the stress and when the speaker assumes that the

first item simply classifies the second, there are two senses and the

stress will usually be placed on the second element.

So, for example, we may find:

What beautiful stained glass

with the stress falling on glass as in:

/ˈwɒt.ˈbjuː.təf.l̩.steɪnd.ˈɡlɑːs/

and then also find:

It's a stained-glass window

with the stress falling on the first element as in:

/ɪts.ə.ˈsteɪnd.ɡlɑːs.ˈwɪn.dəʊ/

revealing that the speaker considers the expression as classifier plus

noun in the first example and as a compound classifier in the second.

|

Pattern summary |

|

Coinages |

Compounding is a common way in which new words are coined and come in a variety of flavours:

- Blends

in which part of either or both words is removed and the resulting morphemes compounded as in, for example:

Oxbridge [a blend of Oxford and Cambridge]

permafrost [a blend of permanent and frost]

simulcast [a blend of simultaneous and broadcast] - True compounds

in which both words are retained and simply combined to make a third as in, for example:

bloatware [a verb-noun compound]

software [an adjective-noun compound]

helpdesk [a noun-noun compound or a verb-noun compound]

etc. - Retronyms

in which an additional classifier is seen as necessary because technology has overtaken the original meaning of a word as in, for example:

rotary telephone

valve radio

hand mower

hand drill

horse drawn carriage

and so on.

There is a good deal more on this in the guide to word formation.

| Related guides | |

| word formation | for more on how this functions |

| word stress | for more on considerations of word stress |

| classifiers, partitives and group nouns | for a guide to a connected area |

| adjectives | for more on the 10+ ways compound adjectives are formed |

| teaching word formation | for the next logical step |

Yes, there's a test.

References:

There's a good deal more on this in

Quirk, R & Greenbaum, S, 1973, A University Grammar of English, Harlow:

Longman (pages 444 et seq.)

Quirk, R, Greenbaum, S, Leech, G & Svartvik, J, 1972, A Grammar of

Contemporary English,

Harlow: Longman