Word formation

If you are here for the first time, you can work through this guide

sequentially but if you are returning to check something, here's a list

of the contents to take you to its various sections.

Clicking on -top- at the end of each section will

bring you back to this menu.

|

Forming new words |

How does English make new words?

Here are some examples:

| drive (verb) | ⇒ | drive (noun) | conversion |

| writer | ⇒ | co-writer | prefixation |

| tick | ⇒ | tick-tock | reduplication |

| cup + board | ⇒ | cupboard | compounding |

| perambulator | ⇒ | pram | clipping |

| motor + hotel | ⇒ | motel | blending |

| happy | ⇒ | happily | suffixation |

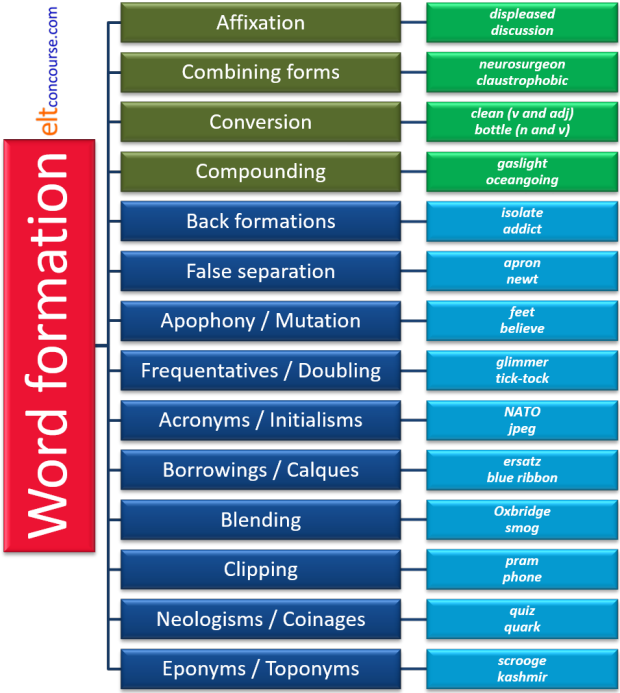

English makes a good deal of use of affixation (either suffix or prefix attachment), compounding and conversion but less of the other means of word formation. (Other languages may include, e.g., infixing in the middle of a word, circumfixing to both beginning and ends of words and so on.) Affixation and Conversion form the main focus of this guide. Compounding deserves a section to itself and a link to that guide is in the list at the end.

Other ways in words are made are also considered below.

|

Stems and base forms |

A word stem is the section of a word responsible for its meaning.

In English, for example, the stem of the word comfortable

is comfort which can stand alone as a meaningful lexeme.

The term stem is used with different meanings when

analysing languages which are heavily inflected. For example,

in many Romance languages, the stem of a verb cannot stand alone and

always appears in combinations with various suffixes denoting

number, gender, person and social relationships.

In the case of English, and other less inflecting languages such as

Mandarin, however, the stem is often indistinguishable from the base

form so we have, for example, the verb put which has no

past forms and only occurs with a suffix in two forms (puts

and putting).

In Spanish, the stem of the same verb is pon- which cannot

stand alone but always appears in combination with suffixes so we

get:

pongo (I put)

pones (you put)

pone (she puts)

ponemos (we put)

ponen (they put)

this makes the stem a bound morpheme (see below) which cannot stand

alone. The stem of an adjective is sometimes referred to as

the positive form to distinguish it from the

comparative and superlative forms.

|

Affixationbuilding new words |

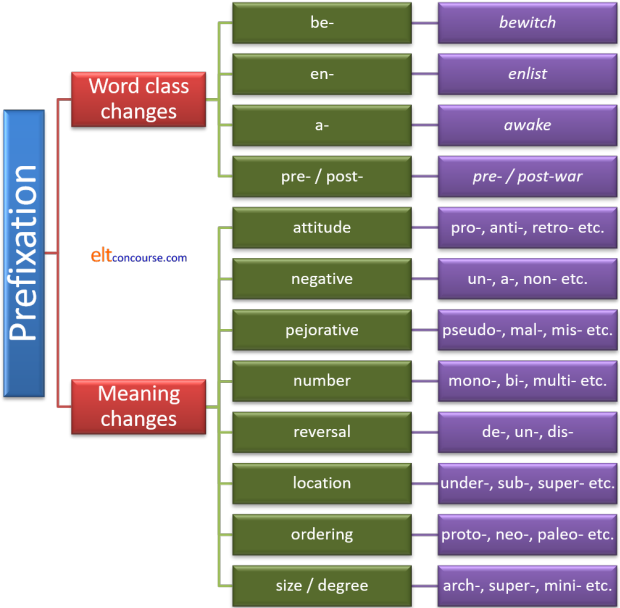

The most important way by far that English forms new words is by deriving them from the forms currently in the language. Affixation is the general terms applied to this in English and affects both word class and meaning.

Here are some examples of affixation with the affixes in black.

|

|

|

|

Figure out what the affixes are doing, their function, and then complete these sentences. Click here when you have.

Inserting a prefix usually changes the __________ but not the

__________.

Inserting a suffix usually changes the __________ but not the basic

__________.

Inserting a prefix

usually changes the meaning but not the

word class.

Inserting a suffix usually changes the

word class but not the basic

meaning.

For example:

Changing friendly to unfriendly produces its opposite

meaning but they are both still adjectives.

Changing happy into happiness produces no basic

meaning change but the word classes are now different

(adjective to noun).

There are exceptions to this general rule:

- The prefixes be- and en- make verbs as in, e.g., bejewel, become, besiege, befriend, enliven, enforce, encourage etc. but the prefixes used in this way are not productive for new coinages.

- The prefix a- makes adjectives from nouns and verbs as in, e.g., asleep, afoot, aground etc.

- The suffixes -less and -ful affect the meaning rather than the word class producing gradable adjective antonym pairs such as hopeful-hopeless, useful-useless, painful-painless etc. but this is not a consistent arrangement because, e.g., helpful and helpless are not antonyms and there are no equivalent antonyms for friendless, boastful and many other adjectives so *friendful and *boastless do not exist.

Morphology is the term given to the study of this area of language and that comes from the term morpheme which is applied to the smallest meaningful units of the language. Morphemes can vary just as phonemes do and have allomorphs so, for example, the suffix denoting ability can be spelled as -able or -ible with no difference in meaning just as a past tense can be indicated by -d, -ed or -t.

|

Combining forms |

Most prefixes and suffixes will affect the meaning of a word or

alter its word class. Some, however, are called combining

forms because they add a new layer of meaning when

they combine with another word or morpheme.

They are not usually considered simple affixes and they occupy a

rather grey area between affixation and compounding. The words

with which they combine are in themselves often independent,

free-standing lexemes and the form adds to the sense rather than

altering it. Combining forms can combine with other combining

forms or affixes as well.

Many of these affixes are used in scientific language as a way of

increasing the meanings contained within an expression. Some

occur with a very narrow range of other items and are not

consistently used.

Here are some examples:

- prefixed forms

- bio- adds the sense of organic life to a word so we

can have, e.g.

biogeography

biochemistry

biomechanics

and so on.

dendro- relates to trees so we can have, e.g.

dendrochronology

neuro- relates to nerves so we can have:

neurosurgeon

neurophysiology

etc.

glosso- relates to language so we can have:

glossogeography

ferro- relates to iron so we can have:

ferromanganese

ferrosilicon

ferromagnet

etc.

cardio- relates to the heart so we can have:

cardiovascular

cardiothoracic - suffixed forms

- -cide relates to killing so we can have:

herbicide

fratricide

etc.

-ology refers to a branch of knowledge so we can have

astrology

sociology

etc.

-phobe relates to fear so we can have:

computerphobe

agoraphobic

etc.

-genic refers to producing so we can have:

anthropogenic

toxigenic

carcinogenic

etc.

-nym relates to names so we can have:

patronymic

eponym (see below)

etc.

Combining forms themselves may combine with affixes and other

combining forms so we get, in addition to some of the previous

examples:

phob-ic

neuro-sis

bi-ology

etc.

The test for whether we are dealing with a simple affix or a combining form is to consider:

- Does the form alter the meaning of what it is attached to or does it add to the meaning? If it is the latter, it is a combining form.

- Can the form stand alone? If it can, it is part of a

compound not a combining form. Combining forms are bound

morphemes, in other words.

(In some analyses, a rather looser view is taken and, for example, the -winner part of breadwinner may be considered a combining form. In this analysis, that would be an example of compounding, not affixation.)

If you would like a list of some combining forms with their meaning and a few examples, click here.

|

Prefixes in Englishadding to the head |

For this part of the guide, you need to download the worksheet.

The first exercise involves sorting the prefixes in the list into groups

under the headings in the table. Do that now and then click

for the answer.

| Prefixes | Type | Meaning and notes | Examples | *Word classes (mostly) | |

|

anti- auto- co- contra- counter- dys- pro- retro- syl- sym- syn- tele- |

Attitude | These describe how things act on each other or are related |

antibiotic antisocial automobile co-driver cooperate contradistinction counterintuitive dysfunctional pro-democracy retroactive syllogism symmetrical synchronous telekinesis |

anti- prefixes

nouns and adjectives auto- prefixes nouns, adjectives and verbs co- prefixes nouns and verbs contra- prefixes nouns, verbs and adjectives counter- prefixes verbs, adjectives and abstract concepts dys- prefixes adjectives and nouns pro- prefixes nouns and adjectives retro- prefixes nouns, adjective and verbs syl-, sym-, syn- prefix nouns and adjectives tele- prefixes nouns and adjectives formed from them |

|

| a- dis- il- im- in- ir- non- un- |

Negative | All

these mean opposite or not but a-

implies lacking in rather than not (compare

immoral and amoral) These prefixes do not attach to negative adjectives so unlovely is possible but *unugly is not im-, il- and ir- are equivalent to in- (not un-) but phonologically determined |

amoral disappear disbelieve illiterate impossible inoperable irreligious non-porous unfailing unjust |

Most of these prefix

adjectives dis- prefixes verbs and derived adjectives and nouns but is often varied with un- so we get: disappearance and disbelief but unbelievable and not *disbeliveable non- prefixes a range of word classes |

|

|

mal- mis- pseudo- quasi- |

Critical / Pejorative | These

are

negative in tone mal- implies badly mis- implies wrongly pseudo- implies falsely quasi- implies apparently but not actually |

malformed malfunction misdiagnosis misdirect pseudointellectual quasi-scientific |

These prefixes attach to abstract nouns, verbs and participles | |

|

bi- centi- deca- demi- di- giga- hemi- hepta- hexa- kilo- mega- |

milli- mono- multi- omni- penta- peta- poly- quint- semi- tetra- tri- uni- |

Number | Most

represent numbers and are derived from Latin or Greek bi- is ambiguous and can denote twice per or twice every so, e.g.: a biennial event may be held twice per year or every second year although the latter meaning is preferred. demi- and hemi- = half mono- = single omni- = all poly- and multi- = many semi- = half or partially uni- = one or united Some mathematical expressions are used loosely and often colloquially to mean large or small as in, e.g., megarich, gigadata etc. |

biweekly centigrade decalogue demigod ditransitive gigabyte hemisphere heptathlon hexagram kilogram megabyte millipede monomania multipurpose omnivorous pentagram petabyte polytechnic quintuplet semidetached tetrapod triathlon unicameral |

These prefixes attach

to nouns, adjectives and adverbs of definite frequency Above three (tri-) the prefixes are generally technical |

| de- dis- un- |

Reversal | All

three prefixes mean reverse an action un- and de- also mean deprive of |

deforest delimit disaffect discolour displeased undo unseat |

un- is also a

simple negative prefix but is reserved for verbs in

this meaning de- prefixes verbs and abstract nouns dis- prefixes verbs, participles and nouns |

|

|

circum- ecto- endo- exo- in- inter- intra- peri- sub- super- trans- |

Place (locative) | circum- =

around ecto- = outside endo- = inside exo-= outside in- = within or in inter- = between intra- = inside peri- = around sub- = below (and smaller than) super- = above (and greater than) trans- = across |

circumnavigate ectomorph endomorph exoskeleton infuse interaction intralingual periscope subscript superstructure transatlantic |

circum-

prefixes nouns and verbs ecto- and endo- prefix nouns and adjectives in- prefixes nouns and verbs inter- prefixes classifiers, verbs and nouns intra- prefixes nouns and classifiers peri- prefixes nouns (and is rare) sub- prefixes nouns, adjectives and verbs super- prefixes nouns and adjectives trans- prefixes verbs and some classifiers |

|

|

ex- fore- neo- paleo- post- pre- proto- re- |

Time and ordering | These

are temporal and refer to after, before, new, old and repeated The prefixes pre- and post- may change the word class when they are applied |

ex-boss foresight neologism paleolithic post-industrial postwar prehistoric prepublication presuppose protolanguage rehearing restate |

ex- prefixes

mostly humans re- and fore- prefix verbs, nouns and derived adjectives paleo- prefixes nouns and adjectives and is also a combining form post- prefixes nouns and adjectives pre- prefixes nouns, verbs and adjectives proto- prefixes nouns and adjectives and is also a combining form |

|

|

arch- hyper- infra- macro- mega- micro- mini- nano- out- over- sub- super- supra- ultra- under- |

Degree or size | arch- =

higher hyper- = much larger infra- = below macro- = large or large scale mega- = very large micro- = very small or small scale mini- = small nano- = extremely small out- = exceed over- = too much (often perjorative) sub- = smaller (or below) super- = greater supra- = above ultra- = beyond under- = smaller |

archbishop hyperspace infrared macroeconomics megaphone microscope micromanaging mini-market nanosecond outplay overcook subheading supernatural supranational ultramarine underpay |

arch- is reserved for

people hyper- prefixes nouns and adjectives infra- prefixes nouns and adjectives macro- prefixes mostly abstract nouns micro- prefixes nouns, verbs and derived adjectives mini- prefixes mostly nouns nano- prefixes nouns for measurement out- and over- prefix verbs and derived participle adjectives sub- prefixes nouns and adjectives super- prefixes nouns and adjectives supra- prefixes adjectives mostly ultra- prefixes nouns and adjectives under- prefixes verbs and derived participle adjectives |

|

Some notes:

- There are more prefixes and examples above than on the worksheet so you may wish to add some to your copy.

- A few prefixes appear in more than one row because

they can have a variety of meanings. Some, especially

number and degree cross over the categories because,

loosely, number may be used for degree as in:

I waited a nanosecond

when all that is implied is a very short time, rather than 10-9 seconds. - Some prefixes are missing from this list: be-, im-, en- and

a- because they do change the word class. For example,

bewitch, enslave, imprison, asleep.

- The prefix be- makes

nouns into verbs from which adjectives may be derived, e.g.:

bewitch, bedevil, bemuse, becalm, besiege

Some words derived this way come from verbs no longer in use (e.g., besmirch). - The prefix im- is rare in this sense but

does make some verbs such as:

imprison, impassion, impound, impanel

The prefix may be seen as a phonologically influenced version of en-. - The prefix en-

makes verbs, e.g.:

enliven, encourage, endure, enlist, enrage - The prefix a- makes verbs or nouns into

predicative adjectives, e.g.:

alive, awake, afoot, aground

- The prefix be- makes

nouns into verbs from which adjectives may be derived, e.g.:

- The prefixes post- and pre- also act

to change word class because they usually convert a

noun to an adjective as in, e.g.:

an event before the war = a pre-war event

a discussion after the meeting = a post-meeting discussion - There are rarer or miscellaneous prefixes such as:

- pan- meaning all as in pan-European

- auto- meaning self as in auto-charging

- vice- meaning deputy as in Vice-President

- The general rule in English is that prefixes are not

stressed so, for example, denationalise is

pronounced as /ˌdiː.ˈnæ.ʃə.nə.laɪz/ with the main stress

unmoved from the root word,

nation, and there is

only a slight secondary stress on the prefix.

However, super- and sub- may be stressed so we get, e.g.:

superman as /ˈsuː.pə.mæn/

and

subway as /ˈsʌb.weɪ/

This is not always the case because supernatural, for example, is pronounced as /ˌsuː.pə.ˈnæt.ʃrəl/ and substandard as /ˌsʌb.ˈstæn.dəd/ and in both cases, the prefix carries only secondary stress.

|

Negative prefixes |

There are six negative prefixes in English but one of them,

in-, has three allomorphs: im-, il- and ir-.

Their use is complicated and it is almost impossible to arrive at

the conventional form by guessing.

They can be subdivided in two ways:

- By meaning:

- Contradictory meaning is the polar

opposite of a concept. For example:

non-military

means the opposite of military and

unorganised

is the opposite of organised.

With this meaning, there is no intermediate stage because the word itself is non-gradable. - Contrary meaning allows for

intermediate stages and occurs with gradable adjectives in

particular so, for example:

unhappy

does not necessarily mean the opposite of happy. It may mean less happy than before, for example. - Privative meaning is the lack of

something so, for example:

amoral

and

asymmetrical

mean lacking in morals or lacking in symmetry. - Reversal meaning occurs with verbs and

is exemplified by:

undo

uninstall

and

detoxify

which all signal a reversal of a process.

- Contradictory meaning is the polar

opposite of a concept. For example:

- By how they form words

- a- and its allomorph an- are only

appended to Latin or Greek derived adjectives and only

signal privative meaning. For example:

amoral

and

anarchy

both signal the lack of a state. - de- is prefixed to verbs and their derived

nouns to signal the reversal of an action or removal.

For example:

decolonise(d)

deselect(ed)

dehumidify

all signal reversal or extraction. - dis- is prefixed to verbs and implies simply

not the action or state so, for example:

disagree = not agree

It can also imply reversal as in, e.g.:

disconnect

disappear

disenfranchise

etc.

The prefix also attaches to nouns, adjectives and verbs with a privative meaning as in:

disarranged

disorganised

disabuse

disconnection

i.e., having no arrangement or no organisation etc. or having arrangement and organisation etc. taken away (that's the meaning of privative).

It was also attached to adjectives such as

dishonest

disgraceful

etc. but is no longer used to form new adjectives. - in- attaches to Latinate adjectives almost

solely and is also now unproductive. For example:

incomparable

inexcusable

indefensible

There are four allomorphs of this prefix determined by the nature of the adjectives to which they are attached. For example:

Before 'l':

illiterate

illogical

Before 'p':

impossible

impolite

Before 'm'

immobile

immature

Before 'r':

irreligious

irreparable

One reason for its unproductive nature may be the possible confusion with its meaning of in, inward or into as in

infuse

ingrain

ingrowing

inlaid - non- is prefixed to adjectives usually and has

a contradictory, ungradable sense as in:

non-eventful

non-partisan

noncommissioned

etc.

Unlike the prefix un- this one does not imply any judgement but simply states a fact. Compare, for example:

It was a non-authorised action

and

It was an unauthorised action

in which the second use of the adjective implies (or can imply) a degree of criticism but the first does not carry that implication. - un- is probably the most productive negative

prefix and attaches to both adjectives and verbs. When

it attaches to verbs it usually signals reversal as in:

unmask

unleash

unlock

etc.

When it is attached to an adjective it signals a contrary but usually gradable meaning as in:

unlucky

unnecessary

unmixed

unknown

etc.

- a- and its allomorph an- are only

appended to Latin or Greek derived adjectives and only

signal privative meaning. For example:

Here's a very brief summary of prefixation. See above

for more examples in each category.

|

Suffixes in Englishadding to the tail |

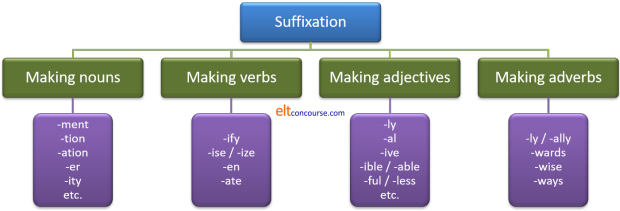

As we noted above, these usually change word class while retaining

the essential meaning of the root form. So friend changes

to friend-ly but the sense remains.

Suffixes are, generally, derivational morphemes making changes to word

class.

Go back to the worksheet and try the task on suffixation before returning and clicking here.

| Making nouns | Making verbs | Making adjectives | Making adverbs | Gender / size marking | ||

| mob-ster plut-ocracy auto-crat social-ite act-or music-al dismiss-al employ-ee organis-ation deci-sion communica-tion insan-ity doctor-ate ideal-ist opera-goer techno-phobe audio-phile boy-hood keep-er Berlin-er |

drain-age happi-ness ideal-ism ide-ology slave-ry cook-ery engin-eer republic-an inhabit-ant manage-ment pig-let hand-ful friend-ship Japan-ese rectifi-cation hard-ware Estonia-n Itali-an million-aire xeno-phobia |

democrat-ize privat-ise simpl-ify deaf-en captiv-ate |

friend-ly music-al observ-ant hero-ic child-like attract-ive compassion-ate inform-ative compet-itive use-ful use-less drink-able admiss-ible doctrin-aire |

Japan-ese hair-y imagin-ary obligat-ory fool-ish courage-ous terrace-d print-ed excit-ing home-ward head-long flouresc-ent bother-some |

happi-ly drastic-ally north-ward(s) crab-wise edge-ways nation-wide head-long |

lion-ess kitchen-ette bride-groom widow-er fisher-woman fisher-man leaf-let beast-ie |

Notice how unbalanced the list is. The majority of suffixes

make nouns or adjectives with fewer making verbs or adverbs.

The adjective formations include -d / -ed and -ing

which are participle adjectives. These may also be formed from

irregular participles so we get, e.g., spelt, broken, lost etc.

as adjectives formed from participles. There are no irregular -ing

endings in English so the issue only arises with past-participle

adjectives.

Some of these forms may be considered combining forms rather than

suffixes proper. See the list linked above, for more.

- Making nouns

- Many suffixes make nouns from other nouns: slav--ery, king-dom,

child-hood, book-let, gang-ster, Trotsky-ite, republic-an, elector-ate,

musket-ry etc.

Only two suffixes make nouns from adjectives: happi-ness, abil-ity etc.

Some suffixes make nouns from verbs: disinfect-ant, hold-er, explor-ation, dot-age, act-or, refus-al, cook-ery, supervis-ion etc.

The suffix -ware is mostly confined to items for sale or manufactured goods as in white-ware, hard-ware, earthen-ware etc.

There is more on how nouns are formed in the guide to that word class, linked below. - Making adjectives

- Many adjectives with suffixes are made from nouns: cream-y,

hope-less, dolt-ish, hope-ful etc.

If the word from which it is derived ends in -l or -le some confusion can arise because the resulting adjective appears to be an adverb (as it ends in -ly). For a list of such words, consult the guides to adjective and adverbs or click here for a list as a PDF document.

Many adjectives are also made from verbs with -ible or -able: extend-ible, enlarge-able etc.

The difference is that removing the -able suffix usually leaves a recognisable word but removing the -ible suffix does not. Compare, for example:

edible

tangible

possible

etc. with

preferable

pronounceable

readable

etc. The first three examples are of what is termed a bound base or bound root (ed-, tang- and poss-). See the guide to morphology for slightly more.

In nearly all cases, the -ible forms are more formal, less common and no longer productive so we have formal-informal pairings such as:

credible - believable

edible - eatable

potable - drinkable

risible - laughable

illegible - unreadable

comprehensible - understandable

incorruptible - unbribable

combustible - burnable

feasible - doable

etc.

There is a wide range of other adjectival formations which differ semantically (see below) - Making adverbs

- There are very limited choices but -ly is by far the

most common: odd-ly, interesting-ly, work-wise, up-wards, width-ways,

country-wide etc. The suffix -wards with

the -s is adverbial only. Without the -s

it can be adverbial or adjectival.

When the adjective ends in -ic, the usual choice is -ally rather than -ly: specific-ally, manic-ally etc.

The suffix -long is rare in the formation of adverbs and head-long and side-long seem the only possibilities. Other such words are adjectival or nouns. - Making verbs

- Choices are limited to 4 suffixes: divers-ify,

person-ify, hard-en, soft-en,

real-ize, item-ise, pontific-ate, differenti-ate etc. (There are, however, some back formations using

-ate to make verbs, such as, desiccate, abdicate etc.)

Verbs may be formed from nouns or adjectives, usually the latter.

Many verbs formed this way are causative in nature meaning that they cause the condition embodied in the adjective or noun from which they are derived. They are called synthetic causative verbs in the trade (hunt down the guide to the causative for more). - Diminutive and feminine suffixes

- Some suffixes which, while

not changing the word class of the base, affect its meaning.

These include:

-let = small or trivial as in booklet, leaflet etc.

-ette

= compact as in kitchenette, maisonette etc.

= imitation as in leatherette, suedette etc.

= feminine as in usherette, suffragette etc. (This use is rare and becoming rarer.)

- ie or -y = affectionate diminutive as in daddy, mummy, auntie, doggie etc.

-ess = feminine as in actress, manageress etc. (This form, too, is becoming rarer but is maintained for marking certain nouns such as lioness, duchess, princess etc. See the guides to markedness and gender, linked below, for more.)

Here's a very brief summary of suffixation. See above

for more examples in each category.

|

Suffixes: semantic functions and formation qualities |

It is not easy to assign semantic rather than grammatical functions to suffixes in the way that prefixes can be handled but there are some general rules concerning some of the most common ones.

Verbs

- -ify, -ise-/ize-, -en

- all signify causative meanings, making verbs from

adjectives, as in socialise,

intensify, humidify, broaden, deafen, strengthen, straighten etc.

The suffix -ate is also causative as in hydrate, fumigate, validate etc. See also the notes on the suffix -ate, below. - -en

- This is an adjective forming suffix (see below) but also a causative verb ending as in, e.g., lengthen, shorten, blacken etc.

- -ate

- is unusual in that it forms both verbs and adjectives

(from verbs and nouns).

When it forms verbs, it is often a combining form rather than a suffix proper because the stem is a bound base which does not appear alone so we get, e.g.:

differentiate

fornicate

desiccate

communicate

adjudicate

duplicate

concentrate

penetrate

illuminate

catenate

collocate

etc. and implies making something of the quality of the base which is a Latin derived form and none of the bases in this list has an independent existence. There is a strong argument that these sorts of words are not formations in English but derived directly from Latin cognates.

Rarely, the base form is a recognisable English word as in, e.g.:

captivate

validate

originate

liquidate

and in these cases the suffix is properly derivational rather than a combining form.

When it is adjective forming, is has the same sense of the quality of something so we get, e.g.:

proportionate

affectionate

carbonate

importunate

intimate

private

etc. and, again, some of the forms come with a bound base which has no independent existence in the language and can, therefore, be analysed as combining forms or as forms derived without affixation directly from French or Latin.

Nouns

- -ness, -ity, -dom, -hood, -ship,-ry, -ery

- imply the state or quality of being something and is

often the way nouns are formed from adjectives: a

kind person exhibits kindness; a brutal

person exhibits brutality. We also have

freedom, wisdom, statehood, brotherhood, fellowship,

hardship etc.

Rarer examples of noun-forming suffixes include -th (growth, stealth), -ery (hostelry), and -red (hatred, kindred).

The -ery suffix, often reduced to -ry or simply -y, sometimes forms nouns concerning the area of work from the worker or person involved (grocery, citizenry, dentistry, bakery, colliery, cutlery, masonry, refinery, cookery, fishery, artistry, banditry, chemistry, forestry, freemasonry, mimicry, peasantry, pottery, puppetry, rivalry, toiletries etc.)

This suffix also makes nouns which refer to a collection of things (cutlery, crockery, drapery, gallery, jewelry, piggery etc.). Additionally, it is used to denote a behaviour pattern (snobbery, trickery, harlotry, gallantry, cajolery, mockery, mimicry etc.)

Latin- and French-derived equivalent suffixes include:

-age (breakage, marriage)

-ance (abundance, brilliance)

-cy (accuracy, lunacy)

-ion (action, decision)

-ice (service, cowardice)

-ment (improvement, judgment, punishment)

-ty (cruelty, frailty)

-ure (pleasure, architecture, pressure).

The suffix -ity often requires the stress to be shifted to the last syllable of the stem so we get, e.g., similar and similarity (/ˈsɪ.mə.lə/ vs. /ˌsɪ.mə.ˈlæ.rɪ.ti/). There is also a shortening of the vowel in many cases so, e.g., chaste (/tʃeɪst/) changes the vowel in chastity (ˈtʃæ.stɪ.ti/). - -ful

- is usually an adjective-forming suffix (see below) but is also also used to mean the amount which a noun contains as in handful, armful, bucketful etc.

- -ware

- is confined to manufactured goods or articles for sale as in homeware, menswear, underwear, kitchenware, software etc. (The suffix is derived from the old word ware meaning an article for sale now almost only seen in the plural.)

- -ee

- usually implies the passive recipient of an action as in employee, deportee, interviewee etc. but, confusingly, the suffix may also denote the active doer of the verb as in escapee, attendee, absentee etc.

- -er, -or, -ster, -goer

- signify the noun doer of an action so we get, e.g.,

baker, painter, doctor, emperor, surveyor, punster, songster

etc.

Rarer versions are -ar (beggar) and -yer (lawyer).

There are numerous Latin- or French-derived suffixes which also signify the doer of an action (often when the verb or noun from which they derive is obscure or outmoded) and they include:

-ain (chieftain, captain)

-ar (scholar)

-en (citizen)

-on (surgeon)

-eer (engineer, musketeer)

-ier (financier, sommelier)

-ary (missionary, expeditionary)

-y (deputy)

-eur (amateur, restaurateur, provocateur)

The suffix -goer also implies the doer of an action but in this case the resulting noun refers to an attendee so we get, e.g., cinemagoer, theatergoer, operagoer etc. Hyphenation is optional but normal on rarer combinations. - -ite, -ist, -eer, -(i)an, -ese, -aire

- all refer in some way to people as:

members of communities: socialite, Trotskyite, Keynesian, communist, Maoist, terrorist etc. (The -ite ending is often used disparagingly.)

nationalities: Japanese, Madagascan, Egyptian etc.

occupations (especially artistic with -ist): pianist, violinist, timpanist etc. and those derived from the nouns they deal with: engineer, puppeteer, musketeer, mountaineer etc.

-aire is rare in this regard forming, e.g., millionaire, billionaire, concessionaire and a few more. It also makes a few rare adjectives but such words are derived directly from French and may not be considered examples of word formation in English.

The suffix -(i)an to denote a resident of a location, an occupation or refer to an historical / literary period often requires a stress movement to the final syllable of the stem: Elizabeth to Elizabethan, magic to magician, Paris to Parisian for example. - -phobe, -phile / -phobia, -philia

- These are often seen as combining forms rather than

examples of simple suffixation. The former refers to

disliking and the second to liking. We get therefore:

technophile, video-phile, bibliophile, haemophilia

computer-phobe, homo-phobe, agoraphobia, claustrophobia

etc.

The terms ending in -ia refer to the condition rather than the person.

Hyphenation is optional on many of these forms but conventional on the rarer combinations. - -ism, -ology, -graphy, -ics

- these noun-forming suffixes refer to areas of knowledge or activity, the first usually to ideologies, the latter three to academic domains: republicanism, monarchism, geology, cosmology, economics, paleogeography etc.

- -ocracy, -crat

- appear in the list above but are probably more

accurately described as combining forms. The first

part of a word so formed is unlikely to be a free morpheme

in English so, while, e.g., democrat and

democracy derive from the Greek demos [people],

the first morpheme is a bound root at best.

See below for the pronunciation issue with these two noun-forming affixes. - -ette, -let, -ling, -ly, -y/-ie, -ess, -man, -woman

- imply a diminutive noun or a term of endearment: starlet,

duckling, beastie, birdie, creepy-crawly, doggy, leaflet,

launderette.

Rarer non-productive examples include -en (maiden, chicken) and -ock (hillock, bullock).

Marking for sex usually falls on the stem to denote female with the non-affixed form used for the male. This is not always the case so while we have, e.g.:

tiger-tigress, count-countess

and more which are falling out of fashion, we also see:

widow-widower, bride-bridegroom

See the guide to gender for more in a complex and controversial area.

Adjectives and Adverbs

- -less and -ful

- sometimes make antonym pairs in an inconsistent and

unpredictable manner such as we saw above but are both

derivational (making adjectives from nouns) and semantic,

altering the meaning so -less means without and -ful

means having as in clueless and useful.

The suffix -less is, incidentally, the only negative-forming suffix in English and is very productive. It occurs in helpless, friendless, moneyless and hundreds more word formations. - -some and -ous

- The suffix -some implies with the quality of

the noun it is formed from

and occurs in, e.g., wholesome, quarrelsome,

troublesome, bothersome, venturesome etc.

There are no antonyms of these with the suffix -less.

Adjectives formed with -ous operate similarly to suggest the quality inherent in the noun from which they are formed as in, e.g.:

joyous, dangerous, envious etc. and some rare ones may form antonyms with -less as in, e.g., joyless.

All words ending in -ous are, in fact adjectives and that is a small fact worth relaying to learners. - -en

- Works as an adjective forming suffix to signify made of as in, e.g., wooden, golden, earthen etc.

- -ic, -ical

- Indicate an adjective formed from a noun and are productive suffixes as in, e.g., heroic, basic, despotic, acidic etc.

- -ary and -ory

- These are mostly now unproductive but were used to make both adjectives and nouns (usually the former) as in voluntary, disciplinary, contributory, seminary, introductory etc.

- -ive / -ative / -itive

- work in much the way that the suffix -ing on

participle adjectives works, that is, it is the state of

something formed from (almost always) the verb. Just

as we have, e.g.:

cooperating

asserting

informing

which all describe what something or someone does, we have parallel adjectives doing much the same as in:

cooperative

assertive

informative

Adjectives with -ative or -itive are often formed from verbs ending in -ate (see above). - -ish, -ly, -y, -ally, -wise, -ways

- -ish forms adjectives which signify somewhat like or akin as in, e.g.,

childish, bluish, mannish etc. Often the suffix

may be added to coin a new word (or nonce word) which can be

adjectival or adverbial such as in

It's getting latish

He's angryish

and so on.

The suffix -y also implies with the quality of and is often applied to weather conditions to form adjectives so we get, e.g., windy, snowy, rainy etc. in addition to wealthy, healthy, slimy, greedy etc.

The suffixes -ly, -ally and -wise form adverbs frequently and mean in the manner of so we get, e.g. manly, godly, friendly, comically, drastically etc. as well as thousands of adverbs derived from adjectives. Less productively, -wise and -ways are used as in, e.g., lengthwise, crabwise, likewise, otherwise, edgeways, sideways etc. and some of these can also be adjectives.

The suffix -aire makes a rare adjective form as in doctrinaire, debonaire but such words are derived directly from French and may not be considered examples of word formation in English.

The suffix -ly usually implies in the form or manner of when the derivation is from a noun to an adjective as in ghostly, hilly, manly, motherly etc. See above for the possible confusion with adverb forms.

This suffix was once the preferred way to form adjectives from nouns and hence there are many adjectives which end in -ly (fatherly, cowardly, earthly and a hundred or so more). The suffix is now reserved for adverb formation and is unproductive in the formation of new adjectives. - -ible, -able

- both form adjectives to imply ability to be as in, e.g.,

regrettable, removable, serviceable, noticeable, credible,

fallible, legible, susceptible etc. The first of

these is unproductive in Modern English but is still common

enough in established words. As was noted above,

however, the removal of the -ible suffix does not

always leave a recognisable Modern English word. There

are, for example, no verbs in English cred, fall

(in this sense), leg (in this sense) or suscept. We

have examples of bound bases.

The pronunciation of the two is indistinguishable (usually /əb.l̩/) and this causes spelling problems for native and non-native speakers alike.

With some words, ending in a -mit, we make an extra change to the morphology by replacing the 't' with 'ss' so, for example, we form the following:

admit → admissible

permit → permissible

omit → omissible

transmit → transmissible

and all such words are formed with the unproductive -ible rather than -able suffix.

The change arises from the way in which Latin forms the words.

Unusually, the adjectives so formed are frequently postpositioned so we get, for example:

the money available now

the houses visible from here

the towns accessible from the motorway - -long, -ward(s)

- imply in the direction of as in, e.g.,

homewards, upwards, leftwards, outward etc.

In these cases, the suffix with the -s ending is adverbial:

travelling homewards

moving rightwards

but we do not (usually) allow:

*a homewards journey

*a rightwards movement

etc.

Without the -s ending, the word so formed can be adjectival or adverbial

travelling homeward

moving rightward

a homeward journey

a rightward movement

The suffix -long is rarer but occurs in, e.g., headlong and sidelong and can be both adverbial and adjectival so we allow both:

She fell headlong

They went in sidelong

and

a headlong fall

a sidelong glance

The suffix -long also implies for a period of so we find yearlong, daylong, month-long, weeklong etc. In this case the product is adjectival, never adverbial and often hyphenated. - -wide

- is reserved for encompassing and occurs in

words such as nationwide, countrywide, worldwide

etc.

The suffix is usually hyphenated when used with nations or other geographical expressions such as Europe-wide, planet-wide, Japan-wide etc. and in these cases can be appended to almost any geographical or political entity so we allow, government-wide, Whitehall-wide, Pacific-wide, school-wide, site-wide, USA-wide, senate-wide and so on.

Words so formed can be adjectival and adverbial. - -most

- implies nearest to and occurs, e.g., in topmost, nethermost, uppermost, innermost, outermost etc. and always forms adjectives.

- Inflections:

- When adjectives are formed by suffixation, the inflected forms for the comparative and superlative are forbidden and the periphrastic forms with more and most are invariably preferred. See the guide to adjectives for more.

|

Spelling rules |

There are a number of spelling rules which apply to the addition of suffixes in English and the conventions may vary slightly between BrE and AmE.

- ending in 'e'

words ending in a consonant + 'e' drop the 'e' when adding anything beginning with a vowel:

response-responsible

versatile-versatility

etc.

However, if there is a need to protect the long vowel, most writers will opt to retain the 'e' as in:

likeable

mileage

etc.

The soft 'c' (/s/) and 'g' (/dʒ/) sounds also mean that the 'e' is retained to protect the pronunciation:

manage-manageable

outrage-outrageous

trace-traceable

etc.

Some adjectives ending in -able can have alternative spellings, with and without the retention of the 'e'. For example:

likeable / likable

loveable / lovable

saleable / salable

sizeable / sizable

useable / usable - words ending in 'ue'

drop the 'e':

argue-argument

true-truly - when the suffixes -ous, -ious, -ary, -ize /-ise, -ation

and -ific are added to the end of a word ending in

-our, the 'u' is dropped so we get, e.g.:

odour-odorous

humour-humorous

labour-laborious

colour-coloration

honour-honorary-honorific

glamour-glamorise / glamorize

discolour-discoloration

When other suffixes (such as -ful, -ite, -less, -able) are used to change word class, this rule does not apply so we get, e.g.:

colour-colourful

favour-favourite

flavour-flavourless

honour-honourable

odour-odourless - Usually, when adding any suffix to a word ending in 'll' we

do not retain the doubled letter so we get, e.g.:

install-instalment

will-wilful

(American spelling often retains the doubled 'l' on many of these.)

However, this rule does not apply to the suffix -ness so we allow:

full-fullness

dull-dullness

well-wellness

|

Constraints |

There are some interesting constraints concerning which

affixes can be used with which base words. Constraints

include meaning (we can't say *unugly), etymology (we

prefer metallic and wooden and can't have *metalen

or *woolic) and phonology (we can have widen

and deepen but not *smallen or *tallen).

For much more on this area, see

the section in the guide to

morphology (new tab).

|

Productiveness |

Some derivational suffixes are no longer used to make new words (or very rarely so) while some are much more productive. For example:

- If you were asked to make an adjective from the verb stroll,

changing

You can stroll there easily

to

It is easily _______________

it is very unlikely that you would produce strollible and much more likely that strollable would be your choice. The suffix -ible is nowadays unproductive and confined to established words. - By the same token, if you were asked to make a noun for a person

from the verb rock, changing

She is rocking the boat

to

She is the _______________ of the boat

it is very unlikely that you would produce rockant or rockist and much more likely that you would opt for rocker. The suffixes -ant and -ist certainly do form doer-nouns from verbs (claimant, inhabitant, accountant, conformist, apologist, tourist etc.) but they are no longer very productive. The suffix -ite is often preferred to -ist in political contexts.

The suffix -ist is productive insofar as many notable politicians have followers or adherents to their causes who are described as Name-ists. - If you were asked to make the noun from sorrowful it is quite likely that you would opt for sorrowfulness rather than sorrowfulity because the -ness noun-making suffix continues to be productive.

- Finally, if you were asked to make an adverb from the adjective foldable (or almost any adjective), it is almost certain that you would select the -ly ending (foldably) over the other alternatives: foldablewise, foldableways etc. None of these three possible alternatives is listed in most dictionaries and most people would have considerably more trouble decoding the last two possibilities than the first choice.

Constraints and productiveness are covered in a bit more detail in the guide to morphology, linked in the list at the end.

|

Pronunciation |

Stress

As is the case with prefixes, suffixes in English are, as a rule , not stressed. There are some exceptions to this.

- The suffix -ette, making diminutive or feminine forms is usually stressed so suffragette is pronounced as /ˌsʌ.frə.ˈdʒet/.

- The suffix -ese denoting nationality as an adjective or representative noun is often stressed so Chinese is pronounced as /tʃaɪ.ˈniːz/.

- The suffix -ation making nouns from verbs is stressed so organisation is pronounced as /ˌɔː.ɡə.nə.ˈzeɪ.ʃən/.

- The suffix -eer, denoting the occupation derived from the noun, is stressed so engineer is pronounced /ˌen.dʒɪ.ˈnɪə/ and auctioneer is pronounced /ˌɔːk.ʃə.ˈnɪə/.

- The suffix -ee denoting the recipient of a verb or the doer of a verb is stressed so escapee and employee are both stressed on the ending as /ɪ.ˌskeɪ.ˈpiː/ and /ˌemplo.ɪ.ˈiː/.

- Some nouns derived from people's names move the stress to the subsequent syllable and the -ian suffix so Darwinian is pronounced as /ˌdɑːrw.ˈɪ.niən/.

- The suffix -ocracy, denoting a system of government similarly requires the stress to move to the syllable before the suffix so democracy is pronounced /dɪ.ˈmɒ.krə.si/. Non-intuitively, the suffix -crat does not lead to this sort of stress movement.

For more on word stress, see the guide, linked below.

Other changes when making verbs and nouns

- Vowel shortening when nouns are formed from verbs is common

so deride is pronounced as /dɪ.ˈraɪd/ with a long vowel

sound (/aɪ/) but derision is pronounce with a shortened

vowel (/ɪ/) as /dɪ.ˈrɪʒ.n̩/.

Similar changes occur with other verb-derived nouns:

decide /dɪ.ˈsaɪd/ and decision /dɪ.ˈsɪʒ.n̩/

divide /dɪ.ˈvaɪd/ and division /dɪ.ˈvɪʒ.n̩/

supervise /ˈsuː.pə.vaɪz/ and supervision /suː.pə.ˈvɪʒ.n̩/

perceive /pə.ˈsiːv/ and perception /pə.ˈsep.ʃn̩/

receive /rɪ.ˈsiːv/ and reception /rɪ.ˈsep.ʃn̩/

expire /ɪk.ˈspaɪər/ and expiration /ˌek.spɪ.ˈreɪʃ.n̩/ - With these words, too, there is often a change from /d/ and /z/ to /ʒ/ as in revise /rɪ.ˈvaɪz/ and revision /rɪ.ˈvɪʒ.n̩/.

- The noun-making -tion and -sion suffixes

as well as the causative -en verb-making suffix are

normally pronounced syllabically with no intervening /ə/ sound.

E.g.:

registration /ˌre.dʒɪ.ˈstreɪʃ.n̩/

exemplification /ɪɡ.ˌzem.plɪ.fɪˈk.eɪʃ.n̩/

correction /kə.ˈrek.ʃn̩/

lengthen /ˈleŋ.θ.n̩/

harden /ˈhɑːd.n̩/

although with the -en suffix, many native speakers insert the schwa and produce

/ˈleŋ.θən/ and /ˈhɑːd.ən̩/ - Final /t/ sounds are routinely changed to /ʃ/ when making

nouns as in, e.g.:

assert /ə.ˈsɜːt/ and assertion /ə.ˈsɜːʃ.n̩/

elevate /ˈe.lɪ.veɪt/ and elevation /ˌe.lɪ.ˈveɪʃ.n̩/

reject /rɪ.ˈdʒekt/ and rejection /rɪ.ˈdʒek.ʃn̩/ - Occasionally, the final /t/ is elided altogether when the

causative -en suffix is used as in, e.g.

soft /sɒft/ and soften /ˈsɒf.n̩/

chaste /tʃeɪst/ and chasten /ˈtʃeɪs.n̩/

haste /heɪst/ and hasten /ˈheɪs.n̩/

|

Back formations |

This is a process akin to affixation but in which the new word is

not formed by adding to the existing word but by analogy with an

assumed but non-existent root. It often involves the removal

of a supposed affix. It always involves a change of

word class so lies within the realm of suffixation. When words

are formed in this way, it is not always a simple matter to

recognise the process and sometimes only research into the words'

origins and first appearances in the language confirm that this has

been the process.

For example, it might be assumed that the word donation is

formed by adding the noun-forming -tion suffix to the verb

donate and dropping the final 'e' in the

conventional way just as relation has been formed from the

verb relate. That is, in fact, not the case.

The word donation is attested from the mid-15th century and

derives from the Latin word donationem. The verb was

formed by analogy and is not attested until 1819.

There are many hundreds of words in English derived by back

formations from existing words. Here are a few examples:

| Word | back-derived from ... | ... by analogy with ... |

| addict | addiction | depict-depiction etc. |

| aggress | aggression | progress-progression etc. |

| automate | automation | decimate-decimation etc. |

| burgle | burglar | other doer nouns ending in /lər/: sprinkle-sprinkler etc. |

| crank | cranky | salt-salty etc. |

| craze | crazy | laze-lazy etc. |

| †edit | editor | audit-auditor etc. |

| enthuse | enthusiasm | *no obvious parallel |

| extradite | extradition | expedite-expedition etc. |

| gamble | gambler | other doer nouns ending in /ər/: tell-teller etc. |

| invite | invitation | explain-explanation (this is uncertain but probable) |

| isolate | isolated | participle adjectives: educate-educated etc. |

| liaise | liaison | an assumed verb root adding -ion (erroneously) |

| †peddle | peddler | an assumption that the -r ending denoted the doer |

| prodigal | prodigality | sentimental-sentimentality etc. |

| sulk | sulky | bulk-bulky etc. |

| televise | television | revise-revision etc. |

† Normally, nouns for doers of actions are derived from the verb so

we get, speak-speaker, hate-hater and thousands more.

Many other verbs, however, have been back-formed from doer nouns and

they include:

babysit, bookkeep, bushwhack, cadge, commentate, curate,

eavesdrop, edit, kidnap, loaf, peddle, shoplift, spectate, swindle

and more.

Most of this guide is concerned with derivation, the affixation

of morphemes to alter word class and meaning in consistent and,

generally, predictable ways.

This is not the only way in which new words are formed and the rest

of the guide is concerned with the alternatives.

|

Conversion |

In this guide, the word conversion is used for the shifting of a word

from one class to another. It is also known as functional

shifting, for obvious reasons.

Because there are no morphological changes when a word is converted from

one class to another, the process is sometimes called zero affixation or

null affixation.

Go back to the worksheet and try the final exercise on this area and then click when you have done it.

Here are the answers:

| Verb → Noun | I doubt he is right → I have a doubt He smiled at me → He replied with a smile He bores me → He's a bore |

| Adjective → Verb | Don't make it dirty → Don't dirty it It will be dry soon → It will dry soon |

| Noun → Verb | Put it in a bottle → Bottle it He's the nurse → He's nursed for years |

| Adjective → Noun | He's a comic actor → He's a comic He's a young man → He mixes with the young |

By far the most common form of conversion in English is the

process of verbification in which a noun is made a verb. It

has happened through most of the history of the language and

continues to be active.

Recent or common examples are

I looked it up on Google → I googled it

I wrote it in ink → I inked it in

She put a coat of varnish on it → She varnished it

We had a talk → We talked

They sent it by ship → They shipped it

They covered it with tiles → They tiled it

and thousands more.

By some estimates, around 20% of all verbs in

English are conversions from nouns.

(The process does not, incidentally occur when the verb is intended

to mean cause something to become. For that we reserve the

causative endings, ise/ize, ify, -ate and -en, as

in, for example, verbify. See above.)

Also by a process of conversion, adjectives may be converted to

nouns and vice versa.

In the former case, for example, and adjective such as green

may be used to refer to part of golf course and the colour of a

team's playing strip may be used with reference to the team itself (the

reds, the blues etc.)

The example above of the young is another case of what are

known as nominal adjectives and that is a frequent occurrence so we

also see

the old

the ill

the poor

the interested

the disqualified

the unmarried

and so on.

When the reverse happens, the result is called a denominal adjective

which is formed by conversion from a noun. This reverse

process results in, for example:

a law practice

wire fences

the emergency services

a silk shirt

and so on.

However, it is not clear that the resulting word is really an

adjective at all or that any conversion has happened because it is

common in English for nouns to classify other nouns without any

magical change in word class so, for example:

the village pump

a glass jug

a garden wall

a spring shower

are all simply cases of nouns acting to classify other nouns which,

if common enough, may even become part of compound nouns.

Conversion may, occasionally, with phrasal verbs and other verb +

modifying adverb constructions be combined with compounding so, for

example, we get:

We don't want anyone to come back to us

on this → We don't want any comebacks

She told everyone how to log on

to the site → She gave everyone their logons

We need to turn this around quickly → We

need a quick turnaround time

|

Nonce words |

Occasionally, it is possible to create new coinages by simple

conversion. For example, the word ask was a verb and

nothing else for centuries but an expression such as a big ask

is only attested from 1987 (in Australian English). It is

now possible to hear the word used as a noun, especially in

sporting and management jargon in expressions such as the ask is

that ... .

Nonce words, if they fulfil a need, may become accepted in the

language. For example, the verb push meaning to

promote an idea or product is attested from the early 18th century

but the noun derived by conversion, as in, e.g.:

The product needs a push

was probably originally a nonce word which filled gap in the

lexicon.

This process is often called suppletion, incidentally, and the

result is known as suppletive form.

|

Shifts in meaning |

Some words, when converted from a verb to a noun or vice versa,

shift their meaning, sometimes greatly, sometimes slightly.

For example:

intimate

is a verb meaning suggest whereas

intimate

is an adjective meaning closely connected to and there is a

minor change to the length of the vowels.

The word

concentrate

as a verb means focus attention but as a noun it refers to

a substance which has been made more powerful and derives from a

different meaning of the verb.

The noun

paper

refers to the material but the verb only means to fix paper to

the wall of a room.

On the other hand

collocate

functions as a verb and a noun with no meaning change.

|

Grammaticalisation |

It is very rare indeed for a language to acquire new words in

closed word classes so we do not, normally, convert words

from a lexical class into a functional class. Verbs do not

become prepositions and nouns do not become conjunctions and so on.

There is, however, a recognisable historical process at work in many

languages, including English, where instances of this do occur.

Because this is an historical process, it is covered in more

depth in the guide to the roots of English, linked below, so only

one example will be used here, that of going.

The word going is, in many cases, a verb form from the verb go and

it carries its usual meaning in, e.g.:

She is going to the shops

which can mean

She is currently on her way to the shops

In Modern English, the verb has been

grammaticalised and now functions as an auxiliary verb denoting

currently planned actions as in, e.g.:

I'm going to talk to the boss tomorrow

The two uses of going can be distinguished because the

function word use to signal a prospective event may be pronounced

weakly (often spelled as gonna). For example,

I'm going to go

may be transcribed

/aɪm.ɡənə.ˈɡəʊ/

but the lexical form is not weakened, retaining the full

pronunciation so, e.g.:

It's going to London

is transcribed as

/ɪts.ˈɡəʊɪŋ.tə.ˈlʌn.dən/

This is a case of a normal intransitive lexical or main verb being converted

to a modal auxiliary verb and similar histories lie behind some

other modal auxiliary verbs such as will.

|

Stress movement |

Some words function both as verbs and nouns. Which

way the conversion goes is slightly arguable. What do you

notice when you read this list aloud?

The export business. Whisky is one Scotland's exports.

He's a convict who was difficult to convict.

Can you give me a discount? Can you discount that?

Don't insult him. That's a nasty insult.

Right. The stress moves. First

syllable for the noun, second for the verb. There are lots of

verb-noun pairs that work like this. The process may be

referred to as phonetic alternation.

For more, see the guide to word stress, linked below. If you

would like a list of the common words which work this way, you can

download it here.

|

Pronunciation |

In addition to the movement of the stress, other changes to the

pronunciation occur. For example:

The verb combat is pronounced as /kəm.ˈbæt/

but the noun is /ˈkɒm.bæt/ with

the first vowel unweakened

record: /’rɛkɔːd/ goes

to

/rɪˈkɔːd/ (with a change to the first vowel from /ɛ/ to

/ɪ/)

abuse: /əˈbjuːs/ goes

to

/əˈbjuːz/ (with a final

consonant change from /s/ to /z/).

combine: /ˈkɒmbaɪn/ to

/kəmˈbaɪn/ (with a vowel change

from /ɒ/ to /ə/ [the first is a piece of farm machinery]).

There is often change in pronunciation of the final consonant

in pairs such as house (noun: /haʊs/) and house (verb:

/haʊz/),

mouth (noun: /maʊθ/) and

mouth (verb: /maʊð/), thief (noun: /θi:f/) and thieve

(verb: /θi:v/).

Usually, but not always,

the spelling changes to reflect the pronunciation.

The general rule is that the consonants /s/, /f/ and /θ/ are

converted to /z/, /v/ and /ð/ respectively:

| noun | verb | ||

| teeth | /tiːθ/ | teethe | /tiːð/ |

| abuse | /ə.ˈbjuːs/ | abuse | /ə.ˈbjuːz/ |

| sheath | /ʃiːθ/ | sheathe | /ʃiːð/ |

For more, go to the guide to word stress, linked below.

|

False separation and misdivision |

A lesser-known or addressed type of word formation occasionally

occurs in English by a process known as coalescence which is also

heavily influenced by pronunciation, in this case the phenomenon

of catenation.

Catenation usually occurs when the consonant sound at the end of one

word joins the vowel at the beginning of the next so we get, for

example, an orange pronounced as a norange (/ə nˈɒ.rɪndʒ/) and

right

arm becomes something like rye tarm (/raɪ.tɑːm/).

Occasionally, this leads to a change in the way the word is formed,

a process called false separation, misdivision or false splitting.

For example:

- The word apron in English derives from the Old French naperon, meaning a small table cloth (originally from the Latin mappa, meaning a napkin). English has changed the word from the original, a napron, to the more familiar an apron.

- The word adder in English derives from the West Saxon word næddre , a snake, and the change is from a nadder to an adder.

- The word umpire in English, meaning a referee derives originally from the Old French nonper, meaning an uneven number and refers to the use of a third person to decide or arbitrate in a game. English has moved from a numpire to an umpire.

More rarely, the phenomenon works in reverse, so, for example:

- The word newt in English derives from the Middle English word evete which became ewte later. Misdivision has given us modern term a newt instead of an ewte.

- The word nickname in English derives from the Middle English ekename meaning an additional name so now by misdivision, instead of an ekename, we have a nickname.

|

Apophony or mutation |

You may see apophony called ablaut, vowel mutation, internal

modification, stem modification or mutation, internal inflexion and

a number of other more or less hideous names.

Simply, it means an internal alteration to a word

to show number, case, person or tense. Modern English makes

more use of external alteration in the form of prefixes and suffixes

but many irregular verbs, pronouns, determiners and plural forms are

still modified for tense, case and number through internal changes.

Old English, in common with many other Germanic languages, ancient

and modern, made a good deal of use of internal mutation or apophony

to signal types of marked meanings. Many of these remain in

the language but few new ones are formed. (An exception is the

slow transformation of the past tense of sneak which is

correctly formed by suffixation as sneaked but is

increasingly formed by internal vowel mutation as snuck.

An allied phenomenon is the slow disappearance of shrank as

the past tense of shrink in favour of shrunk.)

Here are some examples of forms of words made by apophony:

- verb forms

- bind, bound

lie, lay

rise, rose, risen

sing, sang, sung

weave, wove

A list of irregular verb forms, many formed by apophony is available here. - noun to verb formations and vice versa

- advice, advise

belief, believe

blood, bleed

breath, breathe

brood, breed

food, feed

gift, give

life, live

practice, practise

sing, song

wreath, wreathe

With stress movements:

contrast, contrast

export, export

object, object

permit, permit - plurals

- foot, feet

goose, geese

louse, lice

mouse, mice

tooth, teeth

wolf, wolves

wife, wives

Two determiners

that, those

this, these - case formations

- me, my, mine

he, him, his

they, their

us, our

who, whose

There are three allied phenomena which should be mentioned in this context because they all contribute, albeit it historically and rather peripherally, to word formation in English.

- Metathesis

This usually involves the switching of consonants (although there are a number of patterns). Examples of words formed in Modern English from older forms are:

bird (originally bridd)

third (originally thrid)

ask (originally ax) - Apocope

This involves the loss of a sound at the end of words so, for example, father is pronounced in BrE as /ˈfɑːð.ə/ but, in AmE, retains its fuller pronunciation as /ˈfɑːð.r̩/ with a syllabic /r/.

While the word is unlikely to be spelled as fatha any time soon to reflect its pronunciation in British English, the same cannot be said for other examples and the word cuppa is frequently encountered in informal writing and the verb diss, an apocope of disrespect, has gained a certain currency.

Clipping the ends of words (as in photograph to photo) is common and the results usually begin as informal terms but may slowly gain wider use (see below for more examples of clipping and apocope).

All languages, too, exhibit the phenomenon with pet names for people so, e.g., Alexander is often reduced to Alex and Gwendolyn to Gwen etc. - Aphesis

This involves the opposite and refers to the loss of an initial, usually unstressed vowel, sound from the beginning of a word so, e.g.,

till, round and spy

are formed from

until, around and espy respectively.

More examples are given below where the phenomenon is revisited under clipping and blending.

Incidentally, the formation of a form which comes from a

different root and does not resemble a base form at all is the

process known as suppletion which we

encountered with conversions, so we get, e.g.:

go, went, gone (in which the past form is derived

from wend not the Old English gan as the other forms

are)

be, is, am, was, were (in which the forms are

derived from a variety of Old English dialects)

and so on.

This is not a case of word formation per se so won't be

discussed here. The link below to morphology will take you

to a guide with more on suppletion.

|

Frequentatives or doublings |

Many words in English which are now considered simple verbs

(mostly) have been formed by a process of doubling another word and

then reducing it with the addition of one of two suffixes: -er

and -le.

The process is no longer productive in English although people

occasionally will produce nonce words by the same process. It

is probably not a category of much concern to learners and teachers

in practical terms but is included here in a search for

completeness. It is also of some interest to many.

A full list is probably not available anywhere but here are some

examples of this process:

- with -er

- batter (bat + bat)

blabber (blab + blab)

clamber (climb + climb)

flutter (float + float)

glimmer (gleam + gleam)

slither (slide + slide)

spatter (spit + spit) - with -le

- crackle (crack + crack)

crumble (crumb + crumb)

dribble (drip + drip)

muddle (mud + mud)

nuzzle (nose + nose)

prattle (prate + prate)

snuggle (snug + snug)

waddle (wade + wade)

Other languages, notably Slavic ones, Finnish, Greek and Hungarian also make use of this word-formation process, incidentally.

An odd phenomenon in English is that the resulting words may

themselves be doubled (or, to use a small misnomer, reduplicated) to

produce words such as

flitter-flutter

crickle-crackle

spitter-spatter

and so on.

For obvious reasons, such formations are sometimes called ricochet

words.

There is more on this in the guide to idiomaticity which also

explains why we say flitter-flutter and not

flutter-flitter, by the way.

|

Acronyms and initialisms |

An acronym is a word formed from the initials of other words in a

phrase and some are of ancient origin. Most, though, are quite

new. (You may see the phenomenon also referred to as a protogram.)

A distinction can be made between acronyms

proper (which can be pronounced, such as NATO) and those which are

initialisms in which each letter is separately

pronounced (such as CIA). Some of these terms may combine

letter pronunciation and word pronunciation and in some cases

speakers differ in how the terms are pronounced.

A debatable case is the abbreviation ASAP (As Soon As

Possible) which is often pronounced as one word and just as

often pronounced as four separate letters.

Quite commonly, acronyms are formed not just from the first letter

of each word in a phrase (such as ASH: Action on Smoking and Health)

but from the first two or three letters in some or all of the words

(such as RADAR: RAdio Detecting And Ranging). Additionally,

whether functional words (such as and, by, of etc.) are included in the formation

depends on the whether they make the outcome more easily pronounced

or recognisable. From laser, the function word by

is excluded but it is retained in, e.g., DOB (date

of birth).

The convention is to write acronyms in upper case to denote that the

letters stand for words. That is a convention often ignored,

however.

Many acronyms are neologisms (see below).

This is not the place to set out a long list of such formations (you

can hunt the web for those) so we'll confine ourselves to a few

examples of the different sorts which usually are distinguished by

how they are said. Some of these are formed from letters which

many would have difficulty tracing to the source.

| Acronym | Formed from | Pronounced as | |

| laser | Light Amplification by Simulated Emission of Radiation | One word | /ˈleɪ.zə/ |

| NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organisation | One word | /ˈneɪ.təʊ/ |

| ASAP | As Soon As Possible | One word or the initials | /ˌeɪ.es.eɪ.ˈpiː/ or /ˈeɪ.sæp/ |

| scuba | Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus | One word | /ˈskuː.bə/ |

| quango | QUasi-Autonomous Non-Governmental Organisation | One word | /ˈkwæŋ.ɡəʊ/ |

| START | STrategic Arms Reduction Treaty | One word | /stɑːt/ |

| gif | Graphics Interchange Format | One word | /ɡɪf/ |

| wysiwyg | What You See Is What You Get | One word | /ˈwɪz.iː.wɪɡ/ |

| UFO | Unidentified Flying Object | One word or the initials | /ˈju.fəʊ/ or /juː.ef.ˈəʊ/ |

| FAQ | Frequently Asked Questions | One word or the initials | /fæk/ or /ef.eɪ.ˈkjuː/ |

| CD-ROM | Compact Disc Read-Only Memory | As two initials plus one word | /siː.diː.ˈrɒm/ |

| jpeg | Joint Photographic Experts Group | As one initial plus one word | /ˈdʒeɪ.peɡ/ |

| BBC | British Broadcasting Authority | As initials | /ˌbiː.biː.ˈsiː/ |

| FRG | Federal Republic of Germany | As initials | /ef.ɑː.ˈdʒiː/ |

| AAA | Anti-Aircraft Artillery | Triple plus initial | /ˈtrɪp.l̩.eɪ/ |

| W3C | World-wide web Consortium | Initial plus number plus initial | /ˈdʌb.ljuː.θriː.siː/ |

| IOU | I Owe You | I owe you | /ˈaɪ.əʊ.ju/ |

| PIN | Personal Identification Number | Pin (number) | /pɪn.ˈnʌm.bə/ |

Acronyms may be subject to inflexion so we allow, for example,

plural forms, VIPs, FAQs, IOUs, lasers and so on and,

rarely, verbal uses such as OD for overdose which is sometimes

inflected as OD'd for its past tense and participle use.

Conversion of acronyms is also rare but occurs with, e.g.,

scubaing from scuba diving.

|

Borrowing and calquing |

Words are borrowed from other languages in two ways:

- In the original language. These are called

loan words.

For example:

ersatz [from German]

moccasin and tomahawk [both from Powhatan]

kangaroo [from Guugu Yimidhirr]

bungalow [from Gujarati]

veranda [from Hindi]

blighty [from Urdu]

coup d'état [from French]

paparazzi [from Italian]

robot, howitzer [from Czech]

siesta, guerrilla, macho [from Spanish]

karaoke, tsunami, origami [from Japanese]

etc. For a fuller list, see the guide to the roots of English.

Loan words may, in the process of borrowing, be converted in terms of class so, for example, an adjective such as bosh in Turkish, meaning empty, is converted to a noun in English to mean empty or nonsensical talk.

A subset of borrowing is the importation from a dialect of the language into mainstream usage or from one variety of the same language into others. The most obvious cases in English are the loan words which originally existed only in dialects but which have become standard (if colloquial) use and those which have been imported from Australian or American English. For example:

loaf [to mean head or brain, originally from rhyming slang, loaf of bread]

yob [originally back-slang for boy]

selfie [originally Australian slang]

rustbucket [originally Australian]

truck [originally AmE for lorry, now common in BrE]

train station [originally AmE for railway station] - In translation. This is called calquing

and the word or phrase is a calque or loan translation.

For example:

blue ribbon [from the French cordon blue]

loan word [from the German Lehnwort]

it goes without saying [from the French ça va sans dire]

masterpiece [from the Dutch meesterstuk]

devil's advocate [from the Latin advocātus diabolī]

blue-blood [from the Spanish sangre azul]

|

Clipping and blending |

There are two related processes.

- Clipping

A word may be cut, either from the beginning or the end, sometimes both and rarely by removing a syllable internally. For example:

pram [clipped in three ways from perambulator]

zoo [clipped from zoological gardens]

uni [clipped from university]

bus [clipped from omnibus]

plane [clipped from aeroplane or airplane]

hi-fi [clipped and then blended from high fidelity]

mobile [clipped from mobile (tele)phone]

When a word is clipped only at the end, the process (and the product) may be referred to as apocope (see above). Further example are:

hippopotamus → hippo

rhinoceros → rhino

chimpanzee → chimp

public house → pub

advertisement → ad

barbeque → barbie

credibility → cred

disrespect → diss

magazine → mag

cinematograph → cinema

picture → pic

gymnasium → gym

examination → exam

etc.

Often, but certainly not exclusively, the apocope is less formal, sometimes slang.

Additionally the resulting clipped word may be confined to certain uses. For example the clipped form exam is used both formally and informally in educational registers but not in others so while we can have:

a medical exam

and

a medical examination

the former will be a test of a student while the latter will be either a test of a student or an investigation by a medical professional. It is not possible to have, for example:

*The doctor gave her a thorough exam - Blending

Two words may be blended (and often clipped as well) to make a third. The result is often referred to as a portmanteau word. For example:

Amerind [a blend of American and Indian]

biopic [a blend of biography and picture]

brunch [a blend of breakfast and lunch]

docudrama [a blend of documentary and drama]

edutainment [a blend of education and entertainment]

Eurasia [a blend of Europe and Asia]

genome [a blend of gene and chromosome]

Oxbridge [a blend of Oxford and Cambridge]

permafrost [a blend of permanent and frost]

simulcast [a blend of simultaneous and broadcast]

sitcom [a blend of situation and comedy]

smog [a blend of smoke and fog]

telethon [a blend of television and marathon]

webinar [a blend of web (itself a clipping of world wide web) and seminar]

Portmanteau words are often new coinages. Journalists are particularly fond of them, hence Brexit, a blend of Britain and exit, for example.

There is usually enough information in the resulting word to reconstruct its formation.

As is explained in the guide to compounding, linked below, English is a generally right-headed language (so a doorman is a kind of man, not a kind of door, for example), so the right-hand part of the blend is usually the head and determines both meaning and word class. Therefore, sitcom is a kind of comedy not a kind of situation and telethon a kind of marathon, not a kind of television.

(In the literature, two main forms of blending are recognised:- total blending, in which both words are altered in some way as in brunch in which breakfast is reduced to the two letters 'br' and lunch loses its initial letter

- partial blending, in which one word maintains its form unchanged and the other is changed as in, e.g., webinar in which only the word seminar is clipped.)

A third related process which works over time in many languages is the

loss of a sound as a word comes into frequent use. The process