Collocation

There is an essential and simpler guide to collocation in the initial plus section of this site (new tab).

This is quite a long guide so here's a contents list. If this

area is new to you, however, you'd be well advised to read through

the guide in the order in which it is set out.

Clicking on -top- at the end of each section will

bring you back to this menu.

|

Definitions |

A common enough definition is from Lewis:

Collocations are those combinations of words which

occur naturally with greater than random frequency

Lewis, 2008: 25

This simple definition hides a good deal of complexity. We need to understand what is meant by

- combinations of words

- naturally

- greater than random

and we will tackle these one by one later.

Here are a few examples for you to get a feel for collocations.

What goes in the gaps?

Click

here when you have filled the gaps in your head.

here when you have filled the gaps in your head.

| Row 1 | torrential ______ | ______ carriage | high ______ |

| Row 2 | air-conditioning ______ | ______ and fro | towering ______ |

| Row 3 | flock of ______ | an open and ______ case | the black ______ of the family |

| Row 4 | significant ______ | gas ______ | ______ paper |

Some of these are almost entirely predictable because they are strong collocations; some are much weaker collocations and far less predictable.

- In Row 1

- It's a fair bet that you inserted rain or waterfall in the first gap because the word torrential can only describe a limited number of nouns and only functions as an adjective.

- It is unlikely that you decided on a sports carriage although horse-drawn is a popular choice. There are few ways that the noun carriage can be described or classified so the choices are rather limited.

- After high you have a very wide choice although it is vanishingly unlikely that you inserted nouns such as ditch, lawn, car, foot etc. You may have selected a range of other nouns, such as fence, net, window, mountain, table and thousands more possibilities but much less likely that man, tree or baby would have been your choice.

- In Row 2

- Again, the sorts of noun that a phrase such as air-conditioning can classify is quite limited and a good bet is to suggest that either system or unit would be popular choices.

- In the second gap, we have an example of a fixed idiomatic binomial expression. Our choice is limited to the word to and the word fro only occurs in this combination.

- After high in Row 1 you had a very wide choice

but the adjective towering is, although a synonym

of sorts, much less flexible, Again, you will not have

chosen words like ditch, lawn, car, foot etc.

You may have selected a metaphorical use such as rage

or a less figurative use such as trees or

mountains. Movie buffs probably selected

inferno.

If, however, you assumed that it was a non-finite verb form, it's fairly predictable that you inserted the preposition over after it.

- In Row 3

- In the first gap we have a word following what's called an assemblage noun (not a partitive) and you are constrained in English to use a literal word such as birds or sheep but may have opted for a figurative use and chosen something like schoolchildren. Whichever way you went, your choices are severely limited.

- In the second gap, it is almost certain that most people would insert shut as the only viable possibility in English. This is a semi-transparent idiom because, given a little context, the meaning is reasonably clear.

- In the third gap, we have a similar situation of a fixed idiom with only sheep as the possible sensible completion. An idiom such as this is quite opaque in meaning.

- In Row 4

- In the first gap, a very wide range of nouns is possible but they will usually be abstract entities such as advantage, problem, issue, event and so on. It is less likely, but possible, that you selected a so-called concrete noun such as person, woman or monument, however. Your choices were very wide.

- In the second gap, if you assume that the word gas is a noun, it is likely that you selected something which it can classify such as fire, light or chamber. If you assumed it was a verb, then your choices are probably limited to nouns which refer to animate entities.

- Finally, we have another noun so we can either describe

or classify it so you have a very wide choice of words.

If you chose to classify the noun, you may have selected

something like typing, printing, bible, rice or a

number of other classifying nouns. A very wide range

of adjectives is available to you, of course, but they will

probably not have included heavy or impossible.

Less probably, you may have decided to treat the word as a verb and inserted the wall, the living room and so on. In this case the number of possibilities is quite large but still limited.

The moral of this little exercise is twofold:

- Collocation is not random

- Collocation varies in strength

Incidentally, when discussing collocation, the technical terms for the item we are considering is the node. So, for example, when we are deciding which nouns can collocate with the adjective irritating the word itself is the node.

|

Choices and constraints |

If you have followed the guide to lexical relationships, you will be aware of the meaning of syntagmatic rather than a paradigmatic relationships in language. Briefly:

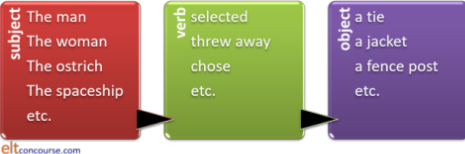

- Syntagmatic relationships

- refer to syntax in a sentence. For example, in this

sentence:

The man selected a tie

we have a subject noun phrase, a verb and another noun object phrase.

The relationships between the three phrases are determined, in all languages, by the grammar of a well-formed sentence so, while we can replace a noun phrase with another and a verb phrase with another to get, for example:

The woman selected a tie

or

The man selected a jacket

or

The man threw away a tie

we cannot replace on a non like-for-like basis and have

*The woman the man a tie

or

*The man selected threw away

Syntagmatic relationships work horizontally along clauses. - Paradigmatic relationships

- work vertically and refer to the fact that The man, The

woman, selected, threw away, a jacket and a tie all perform a

specific grammatical function and can be replaced ad infinitum

with any similarly functioning phrase. The resulting sentence

may be nonsense but it will be grammatically correct so we can have:

The ostrich selected a fencepost

The spaceship chose a tie

and any number of other perfectly grammatical sentences.

The summary is:

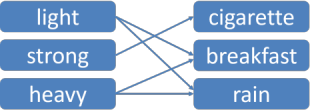

Each slot in a clause can be replaced by words and phrases in the same word class to make new clauses (some of which might make sense) ad infinitum. The boxes relate to items in a paradigmatic relationship with each other and the black arrows show the syntagmatic relationships.

Collocation concerns both types of relationships:

- Collocation is a syntagmatic phenomenon insofar as it concerns

which sorts of items are more or less likely to co-occur

horizontally in a clause. For example, it is more likely that

the verb select will co-occur with an animate subject so we

will not usually encounter:

The tree selected

The car selected

but any animate subject is possible so

The child selected

I selected

The committee selected

The horse selected

and so on are all imaginable. - Collocation is a paradigmatic phenomenon insofar as it is centrally concerned not with what is possible but with what is likely, conventional and non-random in terms of which items are likely to fill the slots.

|

The choice principle: what or which? |

In summary:

- Grammar

- works on an open-choice principle

. The only constraint is word / phrase class, i.e., the

paradigmatic relationships between elements performing the same

grammatical function (verbs, nouns, adverbs, determiners etc.). Whether a sentence is well formed or not merely depends on the

ordering of the items which make up a clause.

We can look at any clause in any language and ask:

What substitutions can we make?

because the choice is virtually open ended. - Collocation

- is a powerful syntagmatic constraint on making

language because it is concerned not with free choice but with

limitations on meaning and what is appropriate and acceptable semantically.

I.e., the issue is one of closed choices and how wide

the choices are is determined by collocational strength.

We can look at a clause in this respect and ask:

Which substitutions can we make?

because the choice is now restricted.

|

Exclusion |

Exclusion is a key concept within collocation.

Some words collocate so freely that almost no combination is excluded. For example, the determiner some will collocate with any plural count noun and any mass noun at all so there is almost no way to predict with which nouns it is most likely to co-occur. For the purposes of analysis, this lack of exclusivity means that it makes no sense to refer to the collocational characteristics of a word like some.

Other words are far less flexible and some almost completely

inflexible so, for example, although the adjective good is

promiscuous in the nouns which it can be used to describe it is not

fully so. We are unlikely to encounter, e.g.:

a good problem

a good drawback

etc. because the adjective is semantically constrained to exclude many

negative-connotation nouns. Not all, however, because:

a good thunderstorm

a good accident

etc.

are conceivable if ironic in most circumstances.

The phenomenon we are describing, which we will encounter frequently in what follows is semantic exclusion. It is a meaning issue.

Other words are very exclusive and are severely constrained in terms

of co-occurrence. For example, the word pay collocates

quite frequently with a range of nouns (bills, invoices, the money,

attention, the price, dividends etc.).

However, the noun attention, which collocates with pay

in, e.g.:

Please pay more attention

has a much more constraining effect on the verbs of which it can be the

object and they are confined almost to pay and give.

What's more, none of the synonyms of pay and give can

be used with the noun attention and only heed appears

to be a synonym of attention which can also be the object of

pay, as in:

Please pay more heed

Furthermore, although the verb pay also has a range of near synonyms,

foot, settle, disburse, give, shell out etc., only some of these can

refer to the same noun:

pay / settle / foot the bill

pay / settle the invoice

pay / disburse / give / shell out the money

give / shell out his pocket money

are all acceptable but

*give / shell out / disburse the bill / the invoice

are not and we can only have:

foot the bill

and not

*foot the invoice

etc.

In our examples, the verb pay and the noun attention collocate strongly in one direction (noun to verb), but the same is not true for collocations in the other direction (verb to noun) which are much less exclusive. There is, in the jargon, asymmetric reciprocity which is explained a little more fully later.

|

Grammatical and Lexical collocation |

Most authorities will agree that there are two forms of collocation to consider: grammatical and lexical.

- Grammatical collocation

- refers to what is analysed elsewhere on this site as

colligation, to which there is a guide linked in the list at the

end.

The principle is that some words are, as it were, primed grammatically to appear in certain grammatical structures.

For example:

The verb differentiate and the noun difference are grammatically primed to take the preposition between

We need to differentiate between the different sorts of figures

What's the difference between the houses?

The adjective interested is grammatically primed for the preposition in (plus an -ing form in the case of verb complementation)

She's not very interested in hockey

I'm interested in seeing the film

The noun pleasure is grammatically primed to take a to-infinitive

It's a pleasure to see you

The verb promise is grammatically primed to take either a to-infinitive or a that clause

I promised to help

I promised that I would help

The noun accident is grammatically primed to be preceded by the preposition by

It was done by accident

and so on.

Some authors will place all prepositional, phrasal and phrasal-prepositional verbs into this category.

This form of collocation will not be further analysed here. For more, see the guides to colligation and multi-word verbs linked in the list of related guides at the end. - Lexical collocation

- is a more equal form of partnership in which both words

contribute to the meaning of the phrase.

For example:

Noun + Verb

The bomb exploded

Verb + Noun

She lost patience

Adjective + noun

a stinging insect

This is the form of collocation which is considered in this guide.

A simple way to remember this difference is to see that

combinations which include function words are grammatical and those

between content words are lexical.

In English, the content words are open-class items (i.e., ones to

which new additions are possible if not frequent) and involve nouns,

adjectives, adverbs and verbs.

Functional (or structural words) are closed-class items (i.e. ones

to which new additions are very rare if not impossible) and involve

prepositions, determiners, conjunctions and pronouns.

Therefore:

Any combination of two or more lexical

words is lexical collocation

Any combination which includes functional words is grammatical

collocation

In this site, the latter is referred to as colligation and analysed elsewhere (see the link below).

|

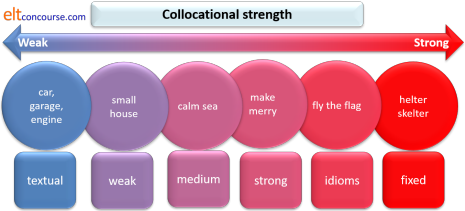

Classification by strength |

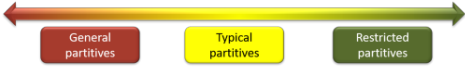

Naturally, some collocations are stronger than others. The nature of collocation can be illustrated like this:

There is probably no principled way in which we can always distinguish, e.g., a strong collocation from an idiom or a binomial although it is easy enough to identify examples of one or the other.

- Idioms

These are pretty much fixed and unalterable expressions in a language. For example, someone can be described as

a one-man band

a jack of all trades

the life and soul of the party

etc.

Things can be talked about as

the odd one out

a blessing in disguise

chicken feed

a flash in the pan

and so on.

There are literally thousands of such expressions in every language which people can deploy almost as if they were single words, saving thinking time and maintaining fluency.

There is a guide to idiomaticity, linked at the end, where more detail is to be had.

The important thing about this kind of collocation is its noncompositionality, i.e., the whole phrase has to be understood as a single item and cannot be broken down into its constituent parts to get at the meaning. - Binomials and invariable collocations

Binomials are a special sort of idiom made up of two elements which always appear in the same order. If they are nouns, they are often used with a singular verb form because they represent a single concept (we say, e.g., supply and demand is the issue not are the issue).

Binomials often contain words found in no other contexts. Examples are:

to and fro

thunder and lightning

spic and span

neither here nor there

in and out

cheap and nasty

etc.

There are also some trinomials in English such as

left, right and centre

bell, book and candle

cool, calm and collected

hook, line and sinker

etc.

A small subset in this category comprises invariable collocations in which only one combination is usually possible in only one order such as:

from top to bottom

back to front

duck a question

stage a play

This kind of collocation is sometimes referred to as Siamese twins. The elements are, in other words, both inseparable and unalterable in the way that other, weaker collocations are not.

Many of these types of strong collocation (and others) are used figuratively as well as literally so, for example:

hook, line and sinker

refers to fishing tackle

but in

She swallowed the story hook, line and sinker

it is used figuratively to suggest that someone was completely gulled into believing something untrue.

These are called duplex expressions and there is more on them below under meaning and in the guide to idiomaticity on this site, linked below.

For example:

His speech was short and sweet

It was something I could not aid and abet

Foreign and domestic policies are being reconsidered

It's a rough and ready rule

In the legal profession, there are many more of these and they include, for example:

heirs and successors

assault and battery

expressed or implied

fit and proper

and many others. - Strong collocations

These can almost always be predicted by native speakers of a language (or at least have very few alternatives). Typically they allow a choice of words but at only one point in the phrase or clause. For example, if you are asked to fill the gap in the following, your answer is probably quite predictable.

Please __________ free to ask any questions.

Some of these collocations allow a choice at two points in the clause or phrase. For example:

swat / squash a fly / wasp / bug

cook / prepare / make a meal / dinner / food / some grub

etc.

Other strong collocations are adjective-noun combinations. The number of possible adjectives for rain is large but not infinite (heavy, light, drizzly, hard, thin etc.) and exclude adjectives such as strong, powerful etc.

Some authors will place all phrasal, prepositional and phrasal-prepositional verbs in the category of grammatical collocation. On this site, they are considered separately. - Delexicalised verbs

When verbs are involved in these invariable collocations they are often describable as delexicalised because they take their meaning from the noun with which they collocate rather than having an explicit meaning in themselves. Other examples of delexicalised verbs (or verbs which can be described as such in certain environments) are:

do | have | get | go | make | put | set | take

For example:

do the washing up

have a shower

get a letter

go by car

make a cake

make the beds

put a question

set a trap

take / make a decision

throw a party / fit / tantrum

in all of which it is the noun which contributes more to meaning than the verb. These general-purpose verbs combine with certain nouns only to produce memorable lexical chunks which native and skilful non-native speakers deploy almost as single lexemes, although adverbials and adjectives may be inserted and tense and voice changed to suit the speaker / writer's intentions. For example:

The point at which strong collocations like these become so predictable and fixed as to qualify as idioms rather than collocations is not at all easy to discern.Verb Collocating nouns do homework, justice to, an injury, a service, a favour, wrong, the shopping, damage get a joke, a job, rid of, married, divorced, old, punishment, arrested give explanations, thanks, consideration, thanks, one's word, promises go mad, home, away, bad, sour, crazy, on holiday, to work have a bath, a shower, lunch, a holiday, a job, a break, a day off, an argument make mistakes, haste, a fuss, arrangements, certain, discoveries, fun of, a journey, peace, war, a mess, money, friends pay attention, a compliment, your respects put aside, a question, an alternative, a suggestion, something in place, together, in prison set a task, a clock, a table, something in place, aside, in context, a recorder take advantage, notice, pains, root, an offer, an interest, place, offence throw a fit, a party, a tantrum, a wobbly

It is also the case that while the choice of make or do to combine with, e.g., the cooking or the dinner seems almost random, other verbs, such as give, take and set do contribute some meaning to the clause although it is still very difficult to guess which one forms the appropriate collocation.

If you would like a list of verbs which may be considered delexicalised or, at least, semi-delexicalised click here.

There is also a lesson for B1 / B2-level learners on delexicalised verbs here (new tabs). - Prime verbs

An allied concept is that of what are known as a language's prime verbs. In English, these are

be | bring | come | do | get | give | go | keep | make | put | take

Besides the delexicalised nature of many of these verbs in certain collocations, they are also the verbs which are basic to most idiomatic language and which often take the place of more formal or synthetic verbs. So, for example:

There are, in fact, very few verbal concepts in English which cannot be rendered less formally and more simply by using one of the prime verbs in combinations with adverbials.We can render ... ... as this with a prime verb He appeared suddenly He was suddenly there They have raised four children They have brought up four children He attended the meeting He came to the meeting I executed her instructions I did as she told me I arrived at the hotel late I got to the hotel late I handed in my essay I gave my essay in He travelled to New York He went to New York Please retain the receipt Please keep the receipt I prepared dinner I made dinner She garaged the car She put the car in the garage I caught the train I took the train - Textual collocation

This refers to the tendency for sets of words to occur together in a text on a particular topic. A text about families will probably include, e.g.:

home, children, parents, arguments

and so on but one about smoking would have

cigarette, health, addictive, nicotine, secondary

etc.

If you want to know more about idioms and binomials, see

the guide to idiomaticity on this site, linked at the end.

If you want to know more about delexicalisation, see the guide to the

lexical approach also linked at the end.

|

Lexical collocation: classification by word class |

The citation from Lewis included the phrase: combinations of words and it is time to address what sorts of combinations we can focus on for analysis.

Lexical collocations can be classified by word class. This is

often a useful way to limit one's focus in the classroom and help

learners to identify collocations of a particular sort so they are, for

example, only trying to notice particular combinations of words, not all

combinations.

At lower levels, the most important combinations are probably

adjective + noun and

verb + noun as these are very frequent

and frequently variable across languages.

The six areas we shall look at are:

| adjective + noun: | high wall, tall person, flat landscape, painful toothache etc. but not painful taste or tall road |

| verb + noun: | close a shop / door etc. but turn off a light |

| adverb + adjective: | ecstatically happy, deeply depressed but not seriously lighthearted or medicinally interested |

| noun + noun: | flock of sheep, herd of goats but not pride of elephants or ingot of chocolate |

| verb + adverb: | scream loudly, tiptoe noiselessly but not scream swiftly or tiptoe violently |

| verb + prepositional phrase: | swing to and fro, descend into misery, explode with anger but not handle with indifference or explode with tears |

You can test yourself to make sure you can recognise stronger and weaker collocation of these six types by clicking here.

Many combinations are excluded for semantic reasons so, for example,

we cannot have:

*short giant

*distinguish similarity

*deafeningly quiet

*window wood

*clarify obscurely

*ascend down the valley

and none of these should cause any difficulty because semantic exclusion

of this sort is common across all languages (and common sense).

|

Six key

concepts: |

Before we can get on to analysing the six types of lexical collocations identified above, we need to consider some key concepts and return to our definition of collocation.

|

Reciprocity |

| give and take |

The relationships between collocating lexemes is often unequal.

There is, in other words, asymmetrical reciprocity. For example, the noun interest

collocates with a wide range of adjectives such as:

great interest

keen interest

obvious interest

sudden interest

academic interest

personal interest

public interest

special interest

romantic interest

and hundreds of other adjectives including:

vested interest

The adjective vested, however, only collocates with the noun

interest

and has no other combination in general English, although in legal and

economic registers we may encounter the technical uses of the terms

vested property and vested authority.

(We are leaving aside the term vested to mean wearing a

vest, by the way.)

Once we have used the term vested, we have almost no choice at all but

to follow it with the noun interest. However, when we use

the noun interest, we are not constrained in anything like the

same way in our selection of an appropriate adjective to modify it.

That is what is meant by asymmetrical reciprocity: collocation does not

work equally in both directions.

The key is to identify what is sometimes referred to as the

pivotal element in the collocation, i.e., the element which is

the determining factor limiting the range of possibilities for the other

element.

Here are some more examples:

The number of nouns which can combine with the adjective heavy

is huge and will include:

weight, car, man, breathing, metal, plate, computer,

stone, table, brick, key, ashtray

and almost every other noun which is not in itself associated with

something light, such as feather or bubble. The

number of possible nouns runs into many thousands.

However, if we take any of these nouns, it is easy to see that the

number of adjectives which can be used to modify them is much smaller

than the number of nouns which can be modified by heavy.

For example, the noun rain can be modified by heavy

but it is clear that the number of other adjectives we can use with this

noun is limited and it is almost possible to produce a complete list

confined to:

| abundant acid blessed ceaseless chill chilly cold constant |

continual continuous cool copious driving drizzly endless excessive |

fine frequent gentle grey hard icy incessant intermittent |

light misty moderate occasional perpetual persistent plentiful refreshing |

relentless soft steady sudden thin torrential tropical warm |

You may be able to think of a few others but the list is clearly not

anything like as long as the list of nouns which can be described as

heavy. The list of possible adjectives would be much shorter

in cases such as computer, ashtray,

breathing etc.

As we saw above, the adjective torrential can only be

used with a small number of nouns and it is possible to come up with a

list such as:

| cloudburst current deluge |

downpour flood monsoon |

rain rainstorm rapids |

river shower storm |

stream thunderstorm waterfall |

and it is quite possible that not all native speakers of English would accept all those as natural combinations. Given that there are probably around 70,000 nouns in English, this means that the adjective torrential collocates with only 0.02% of them. In other words, if you try to use the word randomly to modify any noun you come across, you have a 99.98% chance of being wrong.

Other sorts of collocation work the same way so, for example, the

list of nouns which can be the object of the verb make is very

long but the list of verbs which can have bed as the object is

very much shorter.

The verb babble is also a pivotal or constraining element as is

its derived participle adjective babbling and, apart from

babies and streams, brooks, becks and rivulets it

collocates with very few nouns naturally even though its meaning (to

talk rapidly and incomprehensibly) is common enough and could be applied

to many types of people and noise-producing objects. Native

speakers might or might not accept

babbling tourists

babbling foreigners

babbling gossips

babbling people

etc. as natural combinations.

There is a classroom implication that we need to focus on

collocations which are limited, not on those which are so numerous that

they can't be taught.

Hence, the focus on exclusion at

the beginning of this guide.

|

Separation |

| give and take |

Collocation may be described as the study of how lexemes

conventionally co-occur (are

combinations in Lewis's definition) but that does not necessarily mean that they

must be juxtaposed. For example, we may have:

the dense fog

in which the words are juxtaposed, or

the fog was / became / looked dense

in which the collocating noun and adjective are separated only by

the copulas be, become or look, but we could also have:

the fog which rolled down the mountain that morning

grew increasingly dense

in which the collocates are separated by nine other words.

This is clearly a teaching issue because learners may not be able easily to spot the collocating items in the

following unless they are highlighted in some way, as they are here

with one example of each of the six main types of lexical

collocation:

- The landscape over which they were travelling that morning was featureless

- My hotel bill is the first thing that I need to settle

- She was deeply, and quite obviously to me, upset

- The chocolate looked absolutely delicious so I bought three bars

- He strongly and persistently, throughout the bad-tempered meeting, argued his point

- They fell irretrievably and quite hopelessly into debt

|

Randomness: grammar and presupposition |

| equal probability |

The citation from Lewis at the beginning included the expression: with greater than random frequency.

Language, however, is a non-random phenomenon. It is not the case that one language lexeme may be followed by any other with absolutely equal, i.e., random, probability because language is a rule-based system.

The Oxford English Dictionaries website states that:

The Second Edition of the 20-volume Oxford English

Dictionary contains full entries for 171,476 words in current use ...

Over half of these words are nouns, about a quarter adjectives, and

about a seventh verbs; the rest is made up of exclamations,

conjunctions, prepositions, suffixes etc. And these figures don't take

account of entries with senses for different word classes (such as noun

and adjective).

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/explore/how-many-words-are-there-in-the-english-language/

If we assume, therefore, that we have around 85,000 nouns which could

conceivably be the subjects of around 25,000 verbs, the number of

possible combinations of noun + verb is well over 2 billion. The

number of possible adjective + noun combinations would be over 3.5

billion.

This is clearly not a tenable conclusion and most combinations of words

are, in fact, excluded for one of two main reasons.

For example, if a clause begins:

Because she ...

it cannot be completed with just any item in the language because the

choices are constrained by the grammar and the meaning systems.

- Grammar

because the word cannot, for example, be followed by opening, difficult, so, in the garden, familiar with, all, were or house because there are word-class and other structural constraints which follow from the rules of English grammar. In fact, because neither a noun nor an adjective can come next, something like 75% of the words in English are already excluded.

The linguistic systems of the language will mean, therefore, that only a verb phrase, with or without an adverbial, can follow our example. That still leaves around 25,000 verbs in the language which could conceivably come next.

This is not, strictly speaking, an example of grammatical collocation (see above for that) but an artefact of the language's grammar. - Presupposed Meaning

because language is not a random collection of significations but utilised for the purposes of communication, so the phrase, Because she ..., cannot rationally be followed by:

... doesn't understand, I will ask her to understand

... is alone, she is with people

because no communication properly results (despite being grammatically well formed).

In addition, certain verbs which only take inanimate or animal subjects such as rain, photosynthesize, calve, low, erode, inundate, overflow, pitter-patter, blare, glint, flame, swish, thud and so on are also excluded. We cannot have, therefore:

Because she flamed ...

Because she eroded ...

etc.

This kind of constraint on what words are possible combinations is sometimes referred to as presupposed meaning and by that is meant that a word is assumed to have a certain meaning that cannot be applied to just anything in a language. There are two sorts of presupposed meaning (which overlap to some extent):- Selectional restrictions

To take a non-verb example, meaning will require that the adjectives influential, tiny, glittering, pollinating etc. are unlikely to occur collocated with the noun elephant simply because the ideas of an influential, tiny, glittering or pollinating elephant are not ones that makes sense to (most) users of a language.

Equally, the subject noun an elephant is unlikely to occur with verbs such as explain, buzz, explode, drone, meditate, apologise and so on because that is not what elephants do (presumably).

The number of ways to finish the sentence which begins:

Because the elephant ...

is therefore severely limited by the nature of elephants. Grammatically, of course, most of the 25,000 English verbs can follow but only a very small percentage of that number will make any sense.

With an adjective such as studious for example, we would presuppose a person as the reference because animals and inanimate entities cannot by the nature of the way the world works be studious.

On the other hand, an adjective such as asymmetrical is very unlikely to be applied to a person because it is simply not a characteristic of most people and one such as electromagnetic has a much more limited range of possible nouns which it can modify.

Of course, in poetic language, when all bets are off in this regard, almost any combination is allowed for effect. Most of us, however, are not teaching English to aspiring poets. - Collocation restrictions

These are more central to our concern here and much more arbitrary because they do not depend on our encyclopaedic knowledge of the way the world operates.

For example, in English you brush your teeth but in German you clean your teeth and in other languages other verbs will be used (including polish) on a more or less random basis. In English, too, we take a taxi but catch a train and in other languages, again, different verbs will be used and the concept of catching something as large as a train is obscure.

- Selectional restrictions

What is meant by non-random collocation is, therefore, not a matter of

random vs. systematic phenomena, it is a matter of comparative

degrees of probability. It is

an analogue, not a digital phenomenon. Degrees of probability are

determined grammatically and semantically.

There are, in other words, regularities in the collocational systems of

a language, any language, which reduce

randomness but the system is not random to begin with.

|

Register |

| mapping the data |

Collocational aspects of many words vary according to the context

(i.e., field of discourse) in which they occur. For example,

within a business context a verb such as grow might

collocate with market or business as in:

We need to grow the market

or

They grew the business year on year

but in non-context-specific fields, the verb usually means

cultivate as in, e.g.:

I grow vegetables

or intransitively to mean get larger as in

The children are growing quickly

All specialist fields (registers) have their own internal jargon (or

specific terminology to be more polite) so, whereas a teacher of

language might refer to:

intermediate level

a legislator might refer to

creating a level playing field

a builder might refer to

foundation level

and a sports commentator might suggest a competitor is able to

level the score.

The example above with the verb map is clearly set in an IT

context but a geographer would probably use the verb quite

differently and with different noun objects such as:

map the transport links.

These considerations do not solely apply to verbs, although verb-noun collocations are good examples of the working of register influences:

- Adjectives such as strategic will be used differently,

and collocate differently in military, chess-playing and economic

registers

strategic weapons

strategic moves

strategic industries

respectively, for example.

(See also the way vested collocates across registers, noted above.) - Adverbs such as healthily will be used differently and

be differently collocated by nutritionists and economists

eat healthily

and

profit healthily

for example. - Nouns such as turbulence will be used differently and

be differently collocated by social commentators, scientists and

marital counsellors

street turbulence

turbulence of an airflow

turbulence in a relationship

for example.

In management-speak, one might encounter the term payroll orphans (workers who have been fired) but that combination of nouns is unlikely to appear in any other register.

Context, as usual in language teaching, is crucial.

|

Style |

| dancing, tripping or boogying? |

A concept closely allied to register is style (so closely, in

fact that the terms are routinely confused).

Style is influential in the selection of collocating words because

although:

settle the bill

pay the bill

foot the bill

are all example of phrasal synonymy, as we have seen, they are stylistically variable

from the formal to the neutral and the informal, respectively.

All the sorts of lexical combinations which are identified above are subject to stylistic variations so we may have, for example:

| Formal | Neutral | Informal |

| admirable idea | excellent idea | super idea |

| accede to a suggestion | agree to a suggestion | go along with a suggestion |

| supremely confident | extremely confident | incredibly confident |

| pod of whales | group of whales | bunch of whales |

| speak loquaciously | speak at length | speak long-windedly |

| articulate | say | put into words |

Informally, verb plus prepositional phrase collocations are

frequently alternatives to more formal verbs. It is also averred

that verb + adverb or adverbial combinations are less formal than single-word

parallels (at least when an alternative exists). For example:

go to the next stage

go on

are less formal than

proceed

and

throw away

is less formal than

discard

For more, see the guide to style and register linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Naturalness |

| How natural is it? |

The citation from Lewis also included the phrase: combinations of words which occur naturally. The term naturally here needs a little investigation because it is gradable concept not an on-off attribute of anything. We can define natural in many ways but the essence is that it is not contrived or contrary to some kind of usual, ordinary or expected law.

Naturally(!), among speakers of any language, opinions will vary and

what one speaker finds a perfectly natural combination of words may

appear to another as false, poorly formed or clumsy at best, plain wrong

at worst.

For example, would you be happy to accept all the following as being

'natural'?

| an influential

book a powerful book a dominant book a prominent book a forceful book |

peel the carrot pare the carrot skin the carrot clip the carrot trim the carrot |

eat soundly eat healthily eat beneficially eat nutritiously eat wholesomely |

More to the point, do you think everyone who speaks English as a first language would agree?

It is, in fact, especially with weak- or medium-strength

collocations, very difficult to decide what is and is not natural.

However, to help us these days, we have access via corpus

research to very large samples of

natural language data from which we can see the patterns that are

frequent, those that are unusual and those that do not occur or are

vanishingly rare.

However, frequency is not necessarily a measure of naturalness because

some combinations of words can be infrequent but natural because they

are confined to certain unusual registers and/or contexts.

For example, the terms:

compose language

creep soundlessly

careful operation

heritage phenomena

downsized workforce

matrix management

are, according to some corpus research, really quite rare but the fact

that they do occur with more much than random frequency implies that

they are natural enough and few speakers of the language would wince if

they read or heard them in particular contexts.

Unfortunately, teachers are rarely able to access corpus research

findings in real time in the classroom (although they can when planning

what to teach) so we are thrown back on our intuitions about language

which may or may not be typical of the speech community we represent.

It is rare, in any case, for false collocation to result in incomprehensibility and all these examples of

probably false collocations are clear in terms

of the speaker / writer's intentions:

She was deeply overjoyed

They opted for their Member of the Senate

He was expelled from the army

He has a group of fish in his pond

The wind was very heavy

She rode a new vehicle to work

I need to get a new square of glass put in the window

He dived profoundly in the river

She spoke with happiness

So, we should not become too fixated on the issue of natural

collocations, especially at lower levels where communication of an idea

will often be more important than natural-sounding language.

The point is made below, however, that learners expect some certainty

in terms of what they are told about language and telling them that, for

example:

Well, yes 'strong rain' and 'boiling sunshine' are

possible, I guess, but I wouldn't say it

is rarely reassuring or helpful.

The point is made below, too, that many multi-purpose nouns, often

hypernyms, do not form very natural-sounding collocations so, for

example:

a box of cigarettes

a group of furniture

a container of paint

all sound slightly unnatural but, failing mastery of the terms

carton, suite and pot, they will communicate effectively.

See below for more on noun + noun collocations of this sort.

Equally, mastery of multi-purpose verb phrases such as begin to do /

play will often stand learners in good stead if they do not know

how to say, e.g.:

go in for golf

or

take up knitting

etc.

A point made above concerned the limited range of prime verbs in

English whose mastery allows learners to express an enormous range

of ideas with few linguistic resources. Those verbs are:

be | bring | come | do | get |

give | go | keep | make | put | take

and it is possible to use them to get one's meaning across even if

what one says is collocationally flawed.

The courier brought the parcel to the office

might be better rendered with a verb which collocates more

obviously with the object noun as

The courier delivered the parcel to the

office

but the sense is unimpaired using a prime verb.

Moreover, because prime verbs are often delexicalised, their

collocates are very numerous and the use of prime verbs will often

sound quite natural, especially informally.

|

Meaning and collocation |

Traditionally, collocation is analysed in terms of identifying

which words naturally co-occur and then selecting, analysing,

listing and teaching them in a way that endeavours to make sense of

a very wide area of language study. Lewis (2008) advocates

encouraging learners to notice co-occurrences of words and become

aware of how words they know form partnerships with others.

However, if different forms of meaning are processed differently by

human brains, as may well be the case, there is some mileage in

looking at the different types of meaning which are encoded in

collocations one may encounter in a language.

What follows draws heavily on Macis and Schmitt (2017) although they are not alone in noticing that meaning may be sidelined in the pursuit of an understandable and accessible way of presenting and teaching some of the huge numbers of natural collocations in the language. Others, for example, Xiao and McEnery (2006), cited later, are also focused on meaning rather than structure.

Macis and Schmitt consider three types of meaning encoded in collocating phrases (although they draw on a small number (54) of collocations of adjective + noun and verb + noun collocations only).

- Literal meaning

- Most collocations fall into this category.

For these expressions, it is enough to understand the meanings of the individual words to understand the phrase so, for example understanding:

thunderous noises

run a business

wholly mistaken

spray paint

drive recklessly

keep [something] to oneself

etc. along with thousands more naturally occurring combinations simply requires the learner to understand the meanings of the words and add meaning 1 to meaning 2 to get the meaning of the whole phrase. - Figurative meaning

- Some collocations fall into the realm of idioms in English

and are not understandable through access to the meanings of the

words that make them up. For example:

a big noise

run a risk

escape by the skin of one's teeth

bread and circuses

drive up the wall

bark up the wrong tree

exhibit at least a degree of non-compositionality and are not readily understood by considering the individual meanings of the words that make them up.

Moreover, these collocations may actually be disallowed in a literal sense so while

He's a big noise in the bank

means he is an important and influential figure,

*They were making a big noise at the party

is a false collocation because great, huge, dreadful etc. would be the preferred collocating adjectives for the noun. - Duplex meanings

- Some collocations have a foot in both camps (so to speak).

They have both literal and figurative meanings. For

example:

I enjoy hot potatoes

may refer literally to cooked food

it may also refer figuratively to a difficult and important problem in, e.g.:

In her job she deals with the really hot potatoes

Macis and Schmitt's example is:

one-way ticket

which may refer to a type of travel permission or may refer to an irrevocable step as in, e.g.:

It's a one-way ticket to disaster.

|

Implications |

If, as is claimed, not only in the study cited above, the figurative meanings of collocations may make up as much as 25% of all collocations, there are classroom implications so, teachers need, according to Macis and Schmitt, to:

- Be alert to any possible figurative meanings of collocations that they intend their learners to encounter and notice.

- Be aware of and use corpora data to set collocations in useful co-texts.

- Help learners to guess from context and co-text whether a phrase is meant figuratively or literally by exposing them to both kinds of use.

- Encourage learners in the use of dedicated collocation dictionaries (see below for a little more on these).

This sort of admonition applies equally, of course to the teaching of any lexis so will not come as a sudden revelation. Macis and Schmitt recognise this when they conclude:

collocations cannot be seen as merely the

co-occurrence of words. With collocations, just as with individual

words, meaning matters.

(op cit.: 58)

|

Analysing the six types of lexical collocation |

Some forms of lexical collocation are more frequent and more

frequently troublesome for learners but they are all important (with the

possible exception of verb plus prepositional phrases) to cover if our

learners' ambition to sound natural (whatever that means) in English is to be

fulfilled. Adjective + noun and verb + noun have already been

identified as important areas.

We can now look in a little more detail at these six types one by one.

|

Adjective + noun |

| warm rain |

Some adjectives are so promiscuous that almost no exclusion

is possible and these include:

good, nice, pleasant, lovely

bad, unpleasant, ugly, difficult

and so on.

These adjectives will not collocate with

all nouns, of course, because

certain combinations are semantically virtually impossible, such as:

unpleasant enjoyment

pleasant illness

difficult weather

etc.

However, the range of nouns that they will collocate with is so

large as to be impossible to list exhaustively. They form, in

other words, such weak collocations that they do not commend

themselves as a teaching target.

Other adjectives (most of them) form medium-strength collocations and

can be the target of our teaching and these include:

heavy, strong, weighty, dense, thick, high, tall,

substantial, fat

light, bright, elegant, easy, simple, gentle, cheerful, happy,

thin

and so on. The list can be extended very considerably but this is

a guide, not a dictionary or thesaurus.

With these adjectives, it is possible to extract certain patterns which

can act as rules of thumb for learners to use. For example:

- heavy is usually used with materials and physical objects so we have:

- a heavy car

heavy rain

heavy metal

a heavy person

etc. but the near synonym, weighty, is often reserved for abstract concepts so we may have

a weighty problem

a weighty issue

a weighty influence

a weighty question

etc. in which the adjective heavy is not allowable. - thick and fat are near synonyms in many cases so we can have, e.g.:

- a fat book

a thick book

a fat pipe

a thick pipe

and so on, but this is not always evident because we do not find:

*a thick cow

preferring

a fat cow

or

*a fat cloud

preferring

a thick cloud

or

fat fog

preferring

thick fog

and so on.

The point here is not that certain combinations are wholly impossible but that certain combinations are preferable, more frequent and more natural.

The adjective fat refers to physical size but thick is reserved mostly to express notions of density and that determines the types of nouns with which the words collocate easily. The antonym, thin, is less discerning and expresses both types of notion

a thin cloud

a thin book

etc. - It may be argued that cheerful and happy are also near synonyms but the first applies almost solely to people and the second is more flexible so we can have:

- a cheerful / happy party

a cheerful / happy person

a cheerful / happy face

etc. but we do not usually allow:

*a cheerful accident

*a cheerful meeting

*a cheerful outcome

*a cheerful coincidence

preferring happy in all cases. - easy and simple are synonyms in many cases so we can allow:

- a simple / easy question

a simple / easy problem

a simple / easy sum

but the two words do not always mean not difficult because simple often means not complicated so we find:

a simple machine

not

*an easy machine

and

a simple sketch

not

*an easy sketch

and so on. - strong and powerful are obvious synonyms with different collocations characteristics so we can have, for example:

- strong coffee

strong medicine

strong arguments

strong suggestions

strong foundations

strong tape

and thousands more. We can also have:

powerful medicine

and

powerful arguments

However, the adjective powerful is more constrained and normally reserved to mean producing power so we allow:

powerful engine

powerful muscles

powerful wind

powerful leader

powerful wave

powerful country

powerful man

etc. but when the sense is of a static object, we do not allow powerful as an adjective so, e.g.:

*powerful foundations

*powerful rope

*powerful bolt

*powerful dam

etc. are all unavailable and, conversely:

*strong engine

*strong gun

*strong kick

*strong program

are also unavailable. - small and little are often cited as synonyms in English but do not always share collocational characteristics. For example:

- It is possible to have:

a small / little child, book, house, village, chair

etc. and literally thousands of other nouns are possible, but

?a little city or country

are uncommon and most would select

a small city or country

in preference.

In the comparative and superlative forms, small is always the preferred adjective (at least in adult talk) so we would prefer:

the smallest part

the smaller house

the smaller amount

over

the littlest part

the littler house

the littler amount

almost invariably.

Some adjectives form very strong collocations as we saw with the

example of vested interest above. Other, less extreme,

examples include:

torrential rain

violent crime

glittering career

spoken language / word

sunken ship / boat

superhuman strength / efforts / feat

drifting snow

etc.

attributive and predicative adjective use

Most adjectives can be used attributively and predicatively.

In the former case, the collocation tends to be stronger and more

obvious. For example:

There were some anxious parents outside the

school

vs.:

The parents outside the school were anxious

or

She made a rapid rise to the top of the business

vs.:

Her rise to the top of the business was rapid.

This is even more the case when the adjective in question is

participial. In the latter case, the word is likely to be

interpreted as a verbal use rather than purely adjectival. For

example:

I walked in the freezing rain and wind

vs.:

The rain and wind I walked in were freezing

or

The written word was more memorable

vs.:

The more memorable word was written

classifier vs. epithet

Certain adjectives take on enhanced collocational strength when

used as classifiers (determining the type of noun) or epithets

(describing the noun). For example:

She wrote

a short book

uses short as an epithet to describe the

book, and is not a particularly strong collocation, but

She wrote a short story

is used to classify the kind of story, is not, in

this sense, gradable and is a much stronger collocation, verging on

a compound noun.

Compare, too:

He worked in one of the compact offices

upstairs

with

He bought a compact disc

|

Verb + noun |

| shut the gate |

Many verbs have no particular collocational characteristics but do

exhibit semantic exclusion by their nature. For example, because of

the meanings of the verbs we do not allow:

cut the sky

envelop the letter

decide the similarity

identify the weather

and thousands of other combinations which simply do not make sense (in

any language).

One obvious distinction is that, non-poetically and non-metaphorically, we

restrict a range of verbs such as decide, oppose, prefer etc.

to animate, often human, subjects and others, such as flicker,

resonate, ring, tick, slam, snap, burn etc. to inanimate subjects.

Metaphorically, we can use something like:

She slammed out the door, her patience having finally snapped

but the power of such items rests in ignoring not adhering to the normal

collocational characteristics of the verbs.

Some verbs are only used in English with a certain set of nouns and some nouns require a reciprocally restricted range of verbs of which they can be the object. For example:

- The verbs close, shut, block, switch off, turn off etc. mean more or less the same thing but, in English, collocate differently. We:

- close or shut doors, lids,

roads, taps, programs and shops

turn or switch off lights, radios, computers and taps

block gaps, views and roads

and there is no obvious reason for this as other languages will translate the phrases differently. The antonyms of these verbs (open, switch on, turn on) work similarly.

Style plays a role here because shut and block are often less formal than close, as can be seen from signs, which are normally in more formal, frozen style, so we would get:

Please keep this door closed

rather than

Please keep this door shut

and

ROAD CLOSED AHEAD

rather than

ROAD BLOCKED AHEAD - Nouns also determine the verbs of which they may be objects so, for example, we:

- break and keep promises

catch fire, colds, sight of and diseases

earn gratitude and a living

give promises, consideration, notice, thanks and words

hold meetings

keep secrets

lend a hand

lose confidence and touch

pay compliments, respects, attention

play tricks

run risks and businesses

set examples and sails

strike matches

take an interest, pains, offence, root and steps

throw parties and fits

etc. and in none of these cases is it possible to insert more than a very limited range of other verbs, if it is possible at all because the noun is the dominant item. - Some nouns are only (or almost only) connected with certain behaviours, for example:

- the door / shutter / window / lid slammed

the goats / sheep bleated

the jet / lion roared

the dog barked

the horse reared

the train / lorry / thunder rumbled

the donkey brayed

the bells pealed

the mud squelched

and hundreds more.

Even in those cases where more than one noun naturally collocates with any verb, the list of possible ones will be severely limited. - Inanimate vs. animate subjects

- As well as determining the sorts of object to which a verb can

apply, collocational factors play a role in determining verbs'

subjects. For example, verbs which imply or suggest some kind

of thought process or deliberate action are usually confined to

collocations with human or higher animal subjects so we will find:

Mary considered braking

The cat watched the bird

but not

*The car considered braking

or

*The keyboard leapt off the desk

and the same is true for hundreds of verbs which imply deliberate behaviour rather than a simple material process.

However, we sometimes employ what is called pathetic fallacy for effect so we might encounter:

The car decided not to start

or

The photocopier took the opportunity to break down.

This is, naturally, logical nonsense but that's often the way things appear.

An associated issue is that English is rather untidy in assigning subjects to verbs so we allow:

The tap dripped

The kettle boiled

etc. when other languages will be more logical and refer to the fact that:

The water dripped

or

The water boiled

Ergative uses of some verbs, in which the ostensible grammatical subject is semantically the object of the verb, also seem to break the animate-inanimate rule of thumb so we allow, e.g.:

The book sold well

The door opened

The toast burnt

and so on which are either not allowable or will demand a special verb form in other languages. - Delexicalised verbs

- have been covered above and in these cases it is the noun which

is dominant in providing meaning and in the selection of the

appropriate verb. In other words, inserting verbs before these

nouns is generally a language-specific phenomenon determined by the

meaning of the noun and in some cases only one or two possibilities

exist:

_______ the beds

_______ homework

_______ a nap

_______ an alarm clock

_______ a train / bus etc. to work

_______ lunch

and so on.

|

Adverb + adjective |

| deeply depressed |

Here, too, the semantic properties of the items will exclude

certain combinations in all languages so we can't allow:

*ecstatically miserable

*miserably happy

*genuinely false

*openly untruthful

and so on because such expressions are internally contradictory or

oxymoronic. With adverbs, then, we need to match meaning

reciprocally so we do allow:

ecstatically happy

miserably depressed

genuinely honest

openly relieved

etc. because the meanings of the two elements are complementary.

When the adjective from which an adverb is derived and the following

adjective are too close in meaning, however, we cannot combine the

terms so we don't allow:

*sadly unhappy

*cheerfully happy

*solitarily alone

etc.

The simple rule is that in order to form an acceptable collocation,

the adverb and the adverb must contribute separately to the meaning

of the phrase, not just be repetitious.

However, intensifying adverbs are another matter. They come in three forms and their meaning can usually be summarised as very. How they collocate is often a question of gradability.

- Amplifiers increase the strength of the adjective and operate

differently with gradable and non-gradable adjectives.

- With gradable adjectives the adverbs may indicate the

extreme of the scale (up or down) so we will get, e.g.:

extremely likely

highly preferable

insufferably hot

slightly warm

marginally preferable

very interesting

rather ugly

and so on. - With non-gradable, on-off adjectives, or adjectives which

already represent the extreme of a scale, adverbs simple enhance the

meaning so we may have, e.g.:

hopelessly addicted

deeply mistaken

wholly unique

perfectly complete

totally wrong

wholly ecstatic

perfectly atrocious

etc.

- With gradable adjectives the adverbs may indicate the

extreme of the scale (up or down) so we will get, e.g.:

The two sorts of amplifiers cannot be used

interchangeably. Those reserved for gradable adjectives such as

extremely, enormously, particularly, insufferably, noticeably

etc. do not work with non-gradable or extreme adjectives so we do not find:

*enormously complete

*particularly dead

*noticeably perfect

*slightly atrocious

*very detestable

etc. and we cannot use those amplifiers which work for

non-gradable senses with gradable adjectives so, e.g.:

*wholly cold

*completely hot

*highly tall

*perfectly old

*indescribably nice

*totally lovely

are all disallowed.

- Emphasisers work to express the speaker / writer's feelings and

will collocate very widely so we can have, e.g.:

plainly / obviously / clearly / doubtlessly + right / wrong / good / bad / pleasant / unpleasant

and almost any other adjective so combinations such as

definitely good

obviously difficult

clearly enjoyable

and so on are all allowed.

Because the adverb is acting to express the speaker / writer's view, these items do not take their collocational characteristics from the adjectives. In fact, the lack of any form of reciprocity leads us to believe that they are not collocational phenomena at all. - Downtoners can do three things but collocate differently

depending on what they are doing.

- Compromisers reduce the speaker / writer's sense of

certainty, e.g.:

quite interesting

sort of helpful

etc.

Again, because these express the speaker / writer's position collocation, if it can be called that at all, can occur with almost any adjective. - Minimisers downplay the strength of an adjective so

collocate most naturally with gradable items as in, e.g.:

slightly interesting

probably important

etc. and not

*slightly perfect

*more or less adult

etc. - Approximators serve to suggest that something is almost but

not wholly the case so they collocate most naturally with

non-gradable adjectives as in, e.g.:

almost unique

virtually perfect

etc. but not with gradable concepts such as:

*almost hot

*virtually chilly

*nearly old

- Compromisers reduce the speaker / writer's sense of

certainty, e.g.:

|

Noun + noun |

| candlelight |

Noun + noun collocations occur preponderantly in four forms:

- Compounds or potential compounds

Where the line is drawn between strongly collocating nouns and true compound nouns is not clear cut. For example, we can have weak collocations such as:

loudspeaker switch

and there are numerous other nouns which will collocate with either element:

loudspeaker positions

loudspeaker cable

loudspeaker controls

light switch

light dimmer

light controls

etc.

However, other very strong collocations are, or may become, compound nouns rather than being obviously the subject of collocation. For example:

light + bulb → light-bulb

lamp + shade → lampshade

dish + washer → dishwasher

A simple but slightly unreliable test of whether a combination represents a compound or simply a medium or strong collocation is to pronounce the pairs. Compounds are usually stressed on the first item.

For more on compounding, see the guide, linked in the list at the end. - Nouns for groups which many call collective nouns although on

this site there is a difference which we will observe here.

- Collective nouns

Collective nouns proper are those which represent a collection of entities and to which it is not necessary to add the of-phrase so we do not, for example, often see:

an army of soldiers

a family of relations

a congregation of worshippers

the cavalry of horse riders

a jury of jurywomen

and so on because the collective noun contains the concept of what makes it up. - Assemblages

are nouns to represent the whole made up of its parts and some collocate very strongly with certain things or people. There are lots of these and many of them, especially those for the animal world, are made up or vanishingly rare. Common ones are:

flock of sheep / goats / birds

litter of kittens / puppies

pack of dogs / wolves / cards

shoal of fish

squad of soldiers

swarm of bees

a gang of criminals

and so on. The number of nouns which collocate in this way is limited and teachable, unless one wants to get bogged down with a murder of crows, an exultation of larks, a bank of monitors, choir of angels, nest of vipers and a murmuration of starlings, of course. A hunt on the web for collective nouns will provide long, useless lists and many will not actually be true assemblage nouns.

In terms of colligation or grammatical collocation is it worth observing that both assemblage and collective nouns proper are grammatically singular but often collocate with a plural verb form. We can have, therefore:

the squad of players is here

the squad of players are here

the jury have reached a verdict

the jury has reached a verdict

The use of the plural is either a form of proximity concord (in which the influence of the second plural noun disposes the speaker to use a plural form of the verb) or notional concord (in which the speaker / writer perceives the assembly to be made up of its individuals because they are known).

In most languages and many varieties of English, including AmE, the singular form is the invariable choice.

- Collective nouns

- Partitives

There is a dedicated guide to partitives on this site, linked from the list of related guides at the end. It is enough here to exemplify the collocational aspects of these words by this table, taken from that guide.

piece of

bit of

item of

touch ofact of

ball of

bar of

case of

cloud of

coat of

dab of

drop of

flash of

game ofgrain of

jar of

lump of

measures (pint, meter, acre etc.)

plate of

sheet of

slice of

speck of

work ofrasher (of bacon)

blade (of grass)

loaf (of bread)

pat (of butter)

ear (of cereal crop)

clove (of garlic)

pane (of glass)

lock (of hair)

glimmer (of light)

scoop (of ice-cream)

gust (of wind)

On the left, we have weakly collocating partitives which collocate with a huge range of mass nouns so we allow:

a bit of time

a touch of irony

a piece of meat

an item of information

and so on.

However, the realities of collocation exclusion become evident as we move to typical and restrictive partitives because the noun often determines the only appropriate partitive to use. While piece of can be used with many mass nouns, it cannot be used with nouns which demand certain types of partitives so we do not allow:

*a piece of milk

*a piece of dust

and so on, preferring

a dash / splash / pint etc. of milk

a grain / cloud / speck etc. of dust.

The typical partitives collocate according to the nature of the substance so flat things come in sheets, round things in balls, rectangular things in bars and thin things in slices and so on.

On the far right are some examples of very restricted partitives which are strong collocations and in many cases, although the general partitives may be available, are selected for precision so, for example, we can have

a bit of bacon

but no other noun can follow

a rasher of _______

a loaf of _______

a lock of _______

except, bacon, bread and hair respectively.

Even when a partitive is used quite widely, its use may be restricted by the noun it modifies (another example of asymmetric reciprocity) so we can allow:

bunch of people / keys / arguments / houses / cars / books / chairs / words

and

swarm of attackers / customers / clubbers / football fans

and many more, but we are restricted to the use of bunch when it comes to

bananas, flowers and grapes

and to swarm when we are referring to

bees, ants, mosquitoes and the like. - Classifiers

Many nouns are used quasi-adjectivally to classify other nouns and many of these combinations also verge on compound nouns. Examples of nouns acting as classifiers (which differ from adjectives in that they do not describe, they classify) are:

a village pump

a brick wall

a plastic toothbrush

an electric fire

a customs officer

a paper plate

etc.

See the note above under adjective-noun combinations where it is observed that adjectives used as classifiers increase the collocation strength of the phrase.

|

Verb + adverb |

| shout angrily |

Adverbs may precede or follow the verb and may be separated from

it by other adverbials so we encounter, for example:

He drove into the garage carefully

in which the adverb is separated from the collocating verb by a

prepositional phrase

He carefully drove into the garage

in which the adverb precedes the verb

He drove carefully into the garage

in which the adverb follows the verb

In all these cases we can legitimately speak of verb + adverb

collocates without implying which comes before which.

Again, many adverb + verb combinations are allowed or excluded

for semantic rather than purely collocational reasons so we do not

encounter

*saunter quickly

*stroll excitedly

*gallop slowly

*laugh miserably

*weep happily

and hundreds of other possible combinations because the verbs

themselves imply the kinds of behaviour they express.

This is common to all languages and unlikely to be a source of

difficulty.

As we saw with verb + noun collocations, however, when both items

contribute to the meaning, collocation is frequent so we see:

saunter casually

stroll quietly

laugh happily

and so on.

Again, both parts must normally contribute, not simple repeat the same

meaning so:

*heat warmly

*sleep unconsciously

*fill fully

*relax leisurely

etc. do not occur.

There are numerous exceptions in which the speaker / writer wants to

emphasise the verb with an adverb so we do encounter, e.g.:

stroll slowly

hurtle rapidly

race quickly

etc. These tautologies are often considered stylistically

questionable.

Excluded from consideration here are those verbs whose

combinations with adverbs produces a new meaning. These are

considered in the guide to multi-word verbs. They include,

e.g.:

speak up

come to

bring about

and many, many more.

We need to be slightly careful to distinguish between adverbs as

adjuncts, integral to the clause and modifying how the verb is

perceived, and adverbs as disjuncts (or sentence adverbials) whose

function is discoursal and whose role is to modify the whole of the

clause to which it applies. For example:

He spoke clearly at the meeting

contains an adjunct adverb (clearly) which tells us how he

spoke. However,

Clearly, he spoke at the meeting

contains the same adverb functioning as a disjunct and expressing

the speaker's notion of the truth of the proposition. It tells

us nothing about how he spoke so is not, therefore, an instance of

collocation. Compare, too:

He told me honestly what he thought

which is an example of how honestly collocates with many

verbs to do with communication including speak, explain, talk,

communicate and others and

Honestly, he told me what he thought

in which the adverb is a disjunct and expresses the way the

speaker wants the hearer to understand what is said.

There is a range of more general-purpose adverbs which collocate naturally with a limited range of verbs. For example:

- strongly collocates with

- support, suggest, argue, deny, condemn, oppose, influence, recommend etc.

- badly collocates with a range of negative-outcome verbs such as

- damage, harm, congest, deform, hurt, injure, need etc.

but not with break, destroy, pulverize, demolish etc. because these are not gradable concepts. - greatly collocates with verbs such as

- enjoy, appreciate, relish, value, dislike, disapprove

etc.

but not with verbs which already contain the sense of greatly such as adore, worship, love, hate, deplore, detest etc. - deeply can collocate with a range of negative verbs such as

- hurt, upset, anger, offend etc.

but not with more positive verbs such as

please, enjoy, compliment, hearten etc. - verbs which represent changes will collocate naturally with adverbs expressing extent and speed, for example:

- change quickly

evolve rapidly

alter drastically