Deixis

|

| centred |

Deixis is derived from the Greek word for reference or showing

(the adjective is deictic, incidentally). It

concerns the ability of language to identify objects, times, people

or ideas with reference to something else. In other words, it

refers to things which can only be understood in some kind of

context.

In simpler terms, deixis refers to the way we signal

here or there, now or then and

you or I.

A definition:

The name given to those aspects of language whose interpretation

is relative to the occasion of utterance

Fillmore (1966) in Harman

(1989)

If, for example, you say:

- I like it here

- We can only understand what here refers to by knowing

where you are – here is a relative

not absolute concept of space.

The centre is here. - I like him

- We can only understand what him refers to by

knowing who you are.

The centre is I. - She is going tomorrow

- We can only understand what tomorrow means by

knowing when this is said.

The centre is now.

In the first sentence, here

is an adverb (although some analyses will refer to it as a pro-form

standing for this place) but deictic pointers can fall

into various word classes.

In the second example, the pointer is a pronoun and in the third

example it is another adverb (also classifiable as a noun acting

adverbially, in this case).

|

The centre |

The deictic centre is the place, time or person from which everything else is relative. For example

- I gave it to him (the deictic centre is I – the person from which him can be understood)

- I went yesterday (the deictic centre is the time of speaking: now – without knowing that, yesterday is meaningless)

- I will sit there (the deictic centre is the speaker's position – without knowing that, we have no idea where there is)

It is impossible to understand a simple sentence such as:

We are going there tomorrow

without knowing what the deictic centre is. In other words, we

need to know who is speaking, when they are speaking and where they

are speaking. We also, incidentally, need to know whether

we includes or excludes the hearer.

|

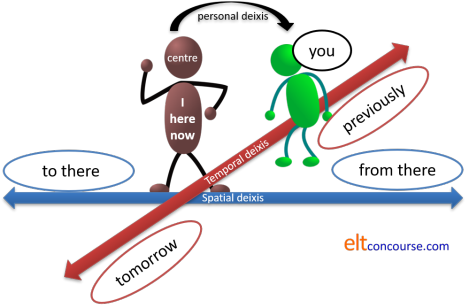

4 types of deixis |

- Personal deixis

- refers to other people (apart from the speaker / writer)

- Temporal deixis

- refers to time other than the moment of speaking / writing

- Spatial deixis

- refers to a place other than here

- Discourse deixis

- is not in the diagram below. It refers to something mentioned earlier in a text (spoken or written) or to something which will follow, in other words, a stretch of discourse. This is sometimes referred to as Textual deixis.

This diagram may help a little.

We can, in fact, move the centre away from the speaker / writer and we often do. For example:

- Keeping the centre in place:

I am going to London soon

The deictic centre is I and now

There is no shifting of the centre because go indicates movement away from here and soon is related to now. - Moving the centre:

I am coming to see you

The deictic centre has been shifted from here to there because come indicates movement towards. In many languages, that would be more logically rendered as

I am going to see you

but, in English, that would be ambiguous because we don't know if the going to bit refers to a current intention or a movement away from here.

In English we conventionally move the centre to the person being addressed. It is considered polite.

This shifting of the centre accounts for a great deal of

confusion with related verbs such as bring-fetch-take and

come-go in English because other languages conceptualise

spatial and temporal relationships differently. Japanese, for

example, always uses the equivalents of come and go

from the point of view of the speaker. German tends also to be

speaker centred in this respect.

It results in

errors such as

*I'll bring you to the station

*I'll go to you now

Are you coming to the cinema with us? *Yes, I'm going.

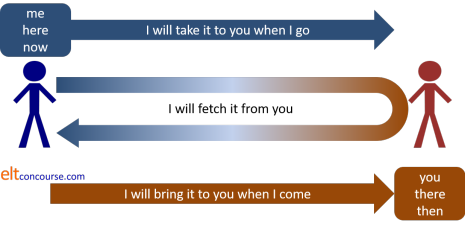

Diagrammatically representing the deictic centre to learners

is often helpful. Like this:

In the last example with bring the speaker remains on

the left but has moved the centre to the hearer on the right, hence

the use of bring rather than take and come

rather than go which would be

the preferred forms in many languages.

Much confusion and distress can be avoided by simply explaining to

learners that in English we often imagine ourselves in the hearer's

place (moving the deictic centre) and that explains why we can say

say:

I'll bring a bottle to John's party next week

The speaker has simply moved the centre to John and therefore is

happy to use a verb which means towards me rather than

away from me.

The speaker could also have said:

I'll take a bottle to John's party next week

without moving the centre but if she were speaking to John on the

telephone, it is almost certain that she would use bring

because that is considered courteous.

Out here on the web, people have posted all kinds of weird reasons

for the anomalous use of these verbs in English but it's actually

quite simple once one is armed with an understanding of the

rudiments of deixis.

|

Personal deixis |

There are three forms of personal deixis:

- Those directly involved – the speaker and the

person / people addressed:

I am leaving now

Can you help? - Third parties not involved in the exchange but the subject

of it:

She's sitting next to you. - People mentioned in the exchange but not nearby or involved

in it:

I wanted to be here earlier but they delayed me

|

Gender and pronouns |

English does not distinguish between nouns by gender unless the

sex is clear but number is another matter. In English,

they is often used to refer to a singular person whose sex is

not known:

The person who wrote this is illiterate;

they can't even spell.

The use of they, their and them to refer to a

singular entity whose sex is not known or irrelevant is attested in

English from at least the 14th century. Only when

Latin-influenced grammarians rose to prominence did the insistence

on the non-marked use of he arise. The use of the

plural pronoun and determiners, they, their, theirs, to

denote a singular referent is making something of a comeback.

English also has no gender marker for plural entities: you,

we, they are all unmarked forms. When we say

They arrived late

we have no idea whether the group is male only, female only or

mixed. We do not even know if we are referring to people or

objects.

Other languages distinguish, e.g., between plural

females and plural males (such as French does with elles

and ils) so it is clear who is being referred to. For

a mixed group, the masculine plural is

used in most languages which make this distinction. However,

in French the word for person is personne and it

is feminine so when the plural (les personnes) is referred

to, the appropriate pronoun is elles even if all the people

are male. Similar phenomena exist in other languages (Spanish,

for example).

There is a guide, linked below, to how languages handle gender and

how gender marking in English may be avoided.

|

Gender and nouns |

Languages which distinguish all nouns by gender (as very many do)

will usually demand the use of the gender-specific pronoun.

For example, in both German and Greek, the word for group

is feminine (die Gruppe, η ομάδα [ee omada]). In these cases,

the feminine pronoun must be used to refer to it, even if everyone

in the group is male. We get, therefore:

The group has arrived and she is getting on her bus

English, incidentally, gets confused here and speakers will use

a plural pronoun to refer to the group (which is clearly a singular

count noun), so we can have either:

The group has arrived and it is getting on

the bus

or

The group have arrived and they are getting

on the bus

We can even allow:

The group has arrived and they are getting on the bus

in which we promiscuously mix singular verb forms with plural

pronoun forms.

For more, see the guide to concord linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Social deixis |

We claimed above that there are 4 main categories of deixis:

personal, spatial, temporal and discourse.

Some writers (e.g., Levinson, 1983) also identify a fifth category,

social deixis. It comes in two flavours:

- Relative social deixis

In many European languages there is a distinction between familiar and polite forms of the pronoun you and the distinction signals closeness and/or formality. This is called the T-V distinction after the French (or Latin) tu and vous forms. German, incidentally, also has a plural familiar form (ihr) which many Romance languages in Europe lack.

Many East- and South-Asian languages, such as Japanese, also have distinguishing honorifics (such as san) which make more complex and subtle social relationships clear.

English is defective in this area, making no distinction in the pronoun between social closeness or distance or even the number of people addressed. It just uses you.

This form of deixis is referred to as relative because its use depends on the relationship between speakers / writers and hearers / readers. For example, whether or not one uses the familiar or polite pronoun for you in most languages which make the distinction depends on closeness of relationship between speakers and sometimes on the addressees' provenance (in Greek, for example, the familiar form is customary for all fellow residents of a village regardless of how well they are known to the speaker). - Absolute social deixis

In this area English is somewhat richer in having conventional ways to address people especially in certain, usually formal, settings. Such terms include, e.g., Your Honour, Ms., Miss, Mrs, Sir, Madam, Your Grace, Captain, Mr President, Your Lordship, Ma'am, Doctor, Ladies and Gentlemen and so on.

Absolute forms such as these are confined to certain settings, of course, and a judge is unlikely to be addressed as Your Honour or My Lord by his family and friends although that term would be used even by close contacts in professional settings.

Even when reference is not direct but to a third person, there are conventions of identification so we speak of, e.g., Her Majesty, His Excellency, Mr, His Honour, Mr Chairman, The Very Reverend and so on.

Levinson (1969) gives examples from many languages in which the use not only of terms of address but also syntax, the entire pronoun system and other language items are dependent on the conventions of social deixis. The conventions apply in some languages, not only to whom one is speaking but also to any reference to a third party and even depend on the status of any bystanders.

|

Empathetic deixis |

This form of deixis is sometimes analysed as a separate type but

here, we'll consider it a subset of social and personal deixis.

It is usually expressed through the use of demonstrative determiners

and pronouns.

It is clear that, in English, that and those are

distal references far from the speaker while this and

these are proximal references, near to the speaker. (For

more, see the following section on spatial deixis.) They are

also used in a metaphorical manner to give a sense of nearness or

distance of abstract ideas.

For example, compare:

This is a problem, isn't it?

These are things we need to deal with

and

That's a problem, isn't it?

Those are things you need to deal with

In the first pair of sentences, the speaker is evoking a sense of

empathy with the use of the proximal pronouns which give a sense of

cooperation and, metaphorically, nearness to both speaker and

hearer. In the second pair of sentences, the speaker has

selected the pronouns to give a sense of distancing from the issue

and there is no or less sense of cooperation and empathy.

Often, a speaker may select a passive structure to enhance the sense

of distance as in, e.g.:

That's something that needs to be dealt with

Those are problems which must be solved

|

Error |

The different ways in which the learners' first languages deal

with personal deixis is the source of a good deal of error such as:

*The team got off the bus and she ran into the stadium.

or

*The group of friends met at 9 and then it went to the cinema.

which is grammatically sound but almost impossible to a

native-speaker's ear.

as well as stylistic errors such as

You give me that

which is fine in languages in which the pronoun is already marked

for politeness but can cause offence in English if no politeness

routine such as Please would, ... I wonder if you could ... etc.

is used.

|

Inclusiveness |

In English the form you refers to other people including

the hearer and does not include the speaker and the form we

includes the speaker(s) and may or may not include the hearers.

Other languages do things differently and distinguish between a

pronoun meaning you not including the hearer and you

including the hearer as well as having a separate pronoun for we

not including the hearer and we including the hearer.

English cannot do this and cannot, additionally, distinguish between

they including a third party and they excluding a

third party.

|

Temporal deixis |

There are two main types of temporal reference:

- Adverbials

The obvious ones are items such as tomorrow, yesterday, the day before yesterday, next year, then, now, afterwards, already, yet, the week before last etc. They are usually adverbs or prepositional phrases acting as adverbials (although an alternative analysis is to call some of them nouns or noun phrases acting as adverbials.).

Absolute dates are excluded from this category so expressions such as the 4th of March 1627 are not deictically related to now in the way that 10 years ago is because it can be understood whenever the sentence is spoken. The prepositional phrase 10 years ago can only be understood by knowing when the statement is made. - Tense forms

There are two types of tense in English:- Absolute tenses such as the past simple or the future with

will. For example:

She sold the house

I will be 35 next birthday

which both refer to time not relative to another time. Deictically, these two utterances are related to now (where we are centred). - Relative or relational tense

forms such as the perfect in English.

For example:

I have broken the lock

I had seen him before

I will have spoken to him

relate deictically to other times:

I have broken the lock

relates to the present because it is now broken and unusable. It is the past within the present.

I had seen him before

relates a more to a less distant past. It is the past within the past.

I will have spoken to him

relates a more to a less distant future. It is the past within the future.

Deictically, relative or relational tense forms relate one time to another, not necessarily the time of speaking.

- Absolute tenses such as the past simple or the future with

will. For example:

For more, see the guides to tense and aspect linked in the list of related guides at the end.

Temporal deixis is problematic when it comes to indirect speech, as we shall shortly see.

Other languages

Some languages do not exhibit relational tense forms so the concepts in English will be obscure. Others may use absolute terms for concepts such as the previous year, the next day etc.

Not understanding the concept of relative time often leads to familiar errors such as:

- mistakenly using an aspect which refers to the present for an

absolute time:

*I have done it in 1984 - mistakenly using an absolute tense form when a relative one is

required (although this is acceptable in some varieties of English)

*I already did it - mistakenly using the simple, absolute form of the tense to

refer to a time relative to a more distant future

*I will speak to him by then

and so on.

|

Spatial deixis |

In Modern English there are essentially two forms:

- Near the speaker

This is a nice place

I am lucky to be here

These are wonderful - Far from the speaker

I want to move there

That was a wonderful place to spend a holiday

I think those look good

Spatial deixis is usually achieved by the use of:

- prepositional

phrases:

She put it in the corner

They live behind the church - demonstrative determiners:

My colleagues gave me that picture

Do you want this disc? - demonstrative pronouns:

She wants those

I'd be happy with this - adverbs:

Leave it there

Go away - nouns (also analysable as nouns acting as adverbials):

They arrived yesterday

They want to go home

Just as tenses are relative and absolute, prepositions exhibit two forms of deixis:

- Relative position, from where the person is, was or will

be.

If the speaker moves, the sentence may no longer be true:

The house is on the left

I can't see it; it's behind the tree - Absolute position, but often relative to something else, in

which the speaker's position is irrelevant.

The sentence remains true wherever the speaker is:

The car park is opposite / outside / near the school

He has a house in the south of Spain

Unless it is otherwise clear from the context, spatial deixis is centred on the speaker / writer but there are many cases when we can move the centre. Here's an example of giving directions over the phone or in an e-mail:

When you get to the lane, look for a blue gate on the left and that is where I live

If one assumes that the addresser is at home, it is clear that

she/he is moving the centre of deixis to the addressee. From

the speaker / writer's point of view, the blue gate is probably not on the

left and this not that is where home is.

The speaker has also moved the time centre to the future, i.e., the moment the person arrives at the lane

and that may be months away.

|

Other languages and spatial deixis |

In English, it is often the case that we project ourselves into another place. We get, for example,

when speaking on the telephone to someone who is at home:

I'm coming home tomorrow

In this case, the addressee is not in the same place as the speaker

and is near to or in the speaker's home. In

effect, we are imagining speaking from where the listener is, not

where we are.

Alternatively, when addressing someone who is in the same

place, we will hear:

I'm going home tomorrow

because there is no need to move the deictic centre. The

verb simply indicates movement away from the current location.

It bears repeating that languages differ in the use of simple verbs

like this and it is a source of error.

In fact, in English, not moving the deictic centre may result in confusion or be deliberately done for comic or dramatic effect. Consider the old Tommy Cooper (an English comedian) joke:

So I rang the guesthouse bell and a lady

opened the window and said:

"What do you want?"

"I want to stay here," I replied.

"Well stay there, then," she said and shut the window.

The key to getting the joke lies in the visitor and landlady's different understandings of here and where the deictic centre should be.

Other languages do not move the centre so easily and that accounts for

phone answering messages in many languages which tell the caller

that

I'm not there

not

I'm not here at the moment.

It also accounts for some confusion between go and come.

For example:

Are you coming to the party?

is not the same as

Are you going to the party?

The first implies either that you are accompanying us / me or that

it is my party in my home we are referring to.

The second carries no such sense and may be referring to a party to

which the speaker has not been invited.

There is rich ground for covert error here.

The verbs leave (and depart) and arrive

may also be subject to the movement of the deictic centre.

Usually, if we ask:

Has she arrived?

we are referring to whether or not she has reached the speaker's

place but that may not be the case because the speaker may be moving

the deictic centre to the hearer and enquiring whether or not she

has reached the hearer.

A similar phenomenon occurs with leave / depart and:

Has he left?

may refer to whether the person in question is no longer in the

speaker's vicinity or no longer in the hearer's vicinity.

Old and Middle English, in common with a range of modern

languages including Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Georgian, Basque,

Korean and Japanese had a third, medial, distinction to describe things far away

from both speakers (yonder is an example)

and many modern languages have this form. It still exists in

some dialect forms of English such as the use of the determiner yon

in Scots.

Modern Standard English can do this but requires a periphrastic form

to make the distinction clear so we have:

this car (proximal and near the speaker)

that car (medial and far from the speaker but

possibly close to the hearer)

and

that car over there (distal and far from

both speaker and hearer)

German uses the same form for the demonstrative determiners that

and those as the definite article but when it means

that or those rather than the, it is

stressed.

Languages which have the threefold

distinction can refer to objects near the speaker, objects

near the hearer and objects far from both the speaker and the

hearer, work like this usually:

- proximal (near me but far from you)

- medial (near you but far from me)

- distal (far from both of us)

Speakers of these languages will often have difficulty deciding which

form is appropriate in English. It results in some covert, and

not so covert,

error such as saying

I want that (when this is meant)

I went here (when came is meant)

and so on.

In other languages, the terms here and there are very differently interpreted and may depend, for example, on whether the place being referred to is at a higher or lower altitude or upstream or downstream from the speaker.

|

Discourse deixis |

We need to be slightly careful to distinguish here between anaphoric and cataphoric referencing and discourse deixis proper.

Referencing within a text is covered in the guide to cohesion

linked in the list of related guides at the end.

It refers to the use of markers to stand for or link to an item

previously mentioned or yet to appear in the text. For

example, in:

When he got to it,

he found the house was much as he had expected;

the place

was old and shabby.

we have two cohesive devices.

- The pronoun, it, which stands for the house and refers forward in the text. That's cataphoric referencing.

- A general term, the place, which refers back and stands for the house. That's anaphoric referencing.

Both references are to something in the text so they are both endophoric references.

Discourse deixis is different because it does not relate

to a specific item but to a stretch of discourse. Such a

stretch of discourse can be very long or quite short. For

example, the novel The Husband’s Secret by Liane Moriarty begins

with the line:

It was all

because of the Berlin Wall.

In this, the marker It refers to everything which

follows, the rest of the novel, not to a particular item. That is discourse deixis.

It needn't be a literary device, of course, although it often is.

Simply responding to an anecdote with

That's fascinating

is an instance where

one person's entire discourse is referred to with the term That.

Equally, we can include in our own discourse something like

...and that's why ...

or

This is a

good one ...

or

Listen to this ...

and those are examples of discourse deixis;

the first anaphoric and the second and third cataphoric.

|

this, these, that, those |

The marker this / these can refer anaphorically to a previous stretch of discourse and cataphorically to something to follow but the marker that / those can only refer anaphorically.

At the end of a presentation or proposal, for example, it is

perfectly acceptable to respond with:

That is an interesting idea

This is an interesting idea

Those are interesting ideas

or

These are interesting ideas

and all the references are anaphoric, referring to the ideas

presented beforehand.

However, we cannot refer cataphorically to what is to follow with that or

those so something like

*I won't be able to come and those are my reasons: firstly, ...

is unacceptable but

I won't be able to come and this is the reason ...

or

I won't be able to come and these are the reasons

...

are both acceptable.

In brief:

this / these: anaphoric and cataphoric

that / those: anaphoric only.

See above under empathetic deixis for how the demonstratives are used to give a sense of nearness (empathy) and distance (lack of empathy).

|

Indirect speech |

| ... and the boss told me she would ... |

Deixis plays a central role in getting reported or indirect

speech right, of course, because by its nature indirect speech is

often a relation of speech which occurred in another place, at

another time and directed to another person. In other words,

the forms are subject to spatial, temporal and personal deixis and

change according to where the centre is at the time of reporting.

Another way of putting this is to refer to the encoding time (when

the statement was made) and the decoding time (when the statement

was reported). If the encoding and decoding times are the

same, few if any changes need to be made to time markers and tense

forms so, for example:

A: I'm coming now

B: What did she say?

C: She said she's coming now

However, if the encoding and decoding times are sufficiently

separated, we do make changes accordingly so the exchange might end

as:

She said she was coming then.

All four forms of deixis are relevant to getting the forms right. There is a guide to indirect speech on the site, linked below, so examples will do here.

- Temporal deixis

Reporting

I am catching the train tomorrow

as

I said I was catching the train the next day

in which the tense form changes along with the adverbial to show that the reporting time centre differs from the time centre when the utterance was made. - Spatial deixis

Reporting

Please put it here

as

The order was to put it outside the garage

in which the fact that the reporting is happening in another place is reflected in the amount of detail which needs to be added to make the sense clear. - Personal deixis

Reporting

Will you please be quiet

as

I was told to be quiet

because the addressee is now the speaker and the pronouns need to be altered accordingly with the shift in deictic centre. - Discourse deixis

Reporting a long turn as something like

She explained in great detail why she was late

is often the preferred form to save time and avoid irrelevant details which, because of the change to the spatial and temporal centre, are no longer required.

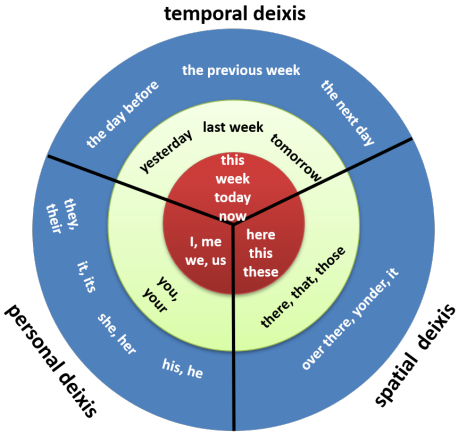

Summary

Discourse deixis is impossible to treat graphically but the other three sorts can be:

Adapted from Harman, 1989.

| Related guides | |

| tense and aspect | for more relational and absolute tenses |

| indirect or reported speech | for the guide to an area which is hard to understand without an appreciation of the role of deixis |

| concord | for more on the problems in English concerning number and reference |

| substitution and ellipsis | for more about how these are used to maintain cohesion |

| cohesion | for more on this area concerning referencing per se |

| pro-forms | for more on pronouns and more |

| semantics | for a general consideration of meaning |

| gender | for the guide to how languages signal gender and how it may be avoided in English |

| language, thought and culture | for a guide which also considers how other languages may encode concepts of time and place and what effect that may have on how one thinks |

| discourse guides | the in-service index to this area |

References:

Harman, IP,

1989, Teaching indirect speech: deixis points the way, English Language Teaching Journal

44-3-8, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Levinson, SC, 1979, Pragmatics and Social Deixis: Reclaiming the

Notion of Conventional Implicature, Proceedings of the Fifth

Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, pp. 206-223

Levinson, SC, 1983, Pragmatics, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Moriarty, L, 2013, The Husband’s Secret,

Barnes and Noble