Anticipatory or existential there and it

Do your learners produce unnatural utterances like these?

- A fire was in the house.

- A seat was empty.

- Learning fluent French by working and living in the country is not difficult.

- Noisy children were in the garden.

- A bank is on the corner.

- A knife is on the table.

If they do, it may be because you haven't focused them on existential sentences or the use of anticipatory or dummy subjects.

|

Two complementary principles |

There are two principles at work here which combine to determine the normal or canonical ordering of factual information clauses.

|

The end-weight principle |

There is a clear tendency in English to place longer and more complex

phrases towards the end of sentences rather than at the beginning.

The key concept here is heaviness. The longer and more complex a

constituent of a clause is, the heavier it is said to be.

For example, modifying a noun with a single adjective as in:

The red car

is a very light way to do so and the tendency in English is to place

light elements such as adjectives, numerals and other determiners before

the noun. That's why, in English, we get:

three cars

not

cars three

(as we do in a range of other languages, including Yoruba and many

African languages as well as Thai and many other South-East Asian

languages).

On the other hand, heavier elements tend to follow what they modify so

we have, e.g.:

The car which I drove for many years when I was a

student

Here is an example of how heaviness affects how natural-sounding a sentence is. Read the following aloud and decide which to you seems the most natural, normal way to order the items in the sentence. Then click here:

- The problem was John's complete and absolute denial that there was something seriously wrong with the car.

- John's complete and absolute denial that there was something seriously wrong with the car was the problem.

Which of them sounded more natural to you?

If you chose

sentence 1., you are in the majority.

Sentence 2. flouts the

end-weight rule by placing the heavy (i.e., more complex) expression at

the beginning. The end-weight principle accounts for a great deal

of word ordering in English which is otherwise not easily explained.

|

The end-focus or old-before-new principle |

The other principle at work in English is the fact that new information is placed towards the end of sentences. Here's a very clear example (from Bruno, no date):

- Every Tuesday, Samantha takes her dog to the dog park near her house. The city of San José maintains the dog park in an effort to promote healthy lifestyles. The city of San José sustains several dog parks throughout the city.

- Every Tuesday, Samantha takes her dog to the dog park nearby her house. The dog park is maintained in an effort to promote healthy lifestyles by the city of San José. The city of San José sustains several dog parks throughout the city.

It is easy to see that 4. flows more easily than 3. because the reader is led through the three sentences by reference to old information before the introduction of new information. This is an example of theme-rheme structuring. (For more, go to the guide the theme-rheme structure, linked in the list at the end of related guides.)

|

So what? |

Taken together, the end-weight and end-focus principles have a powerful effect on word order in English, even though the language is often said to have a very firmly fixed word order. The effect is twofold:

- Extrapositioning:

The notional subject of the verb is moved towards the end of the clause, a phenomenon known as postponement, so instead of:

The fire did the damage

we might have

It was the fire that did the damage

and instead of

Some children were damaging the garden

we might have

There were some children damaging the garden - Fronting:

An anticipatory or dummy subject fronts the sentence but, unlike most cases of fronting, this is in fact the unmarked rather than marked form in English (and that is not so in many languages). For example, fronting an adverb usually marks it in some way for special emphasis, so the difference between:

Yesterday, I went shopping

and

I went shopping yesterday

is that in the first case the time is marked as especially important and in the second, it is not.

However, this is not the case for anticipatory there and it clauses so

There is a snake in the garden

is the normal, unmarked, way of stating a fact in English

but

A snake is in the garden

is less common and therefore more strongly marked.

The resulting sentence contains two subjects: the clause which is what we would normally expect to be the subject of the verb and the anticipatory subject, there or it.

A second reason for focusing on this area in our teaching is that it

is by no means straightforward, as we shall see and avoiding errors such

as:

*Anything can't be wrong

*To learn a new language is fun

etc.

is mostly a matter of knowing how anticipatory, dummy subjects are used

in English and being aware of the fact that this is the

normal way of stating facts.

That may be in contradistinction to the way in which the learners' first

language(s) operate(s).

|

Existential there clauses |

Compare these two sentences:

- There is something rather strange and frightening about him.

- Something strange and frightening is about him.

Sentence 6. sounds strange even though it is grammatically

correct. What English does here, to comply with the end-weight

principle, is to insert a dummy subject and allow the noun phrase to be

shifted to the end of the sentence. Unsurprisingly, this is called

'shifting' in the literature.

(Note here that we are talking about there as a dummy subject,

not there as an adverb. When the word is an adverb it is

usually stressed

There's John!

Please sit

there

but when used as a dummy, it is unstressed

There's a bank on the corner.

Here are some more examples of the ways English can use the dummy or existential there:

- There can't be anything very wrong.

- There was someone playing the piano in the house.

- There are good reasons for the problem.

- There have been some nasty incidents recently.

- There's a man with a dog in the garden.

Now try to alter the sentences to avoid the existential there and see what you get. Click here when you have done that.

If you try to alter those sentences to

avoid the dummy there, you get rather odd and

unacceptably foreign-sounding results like:

*Anything can't be wrong

?Someone playing the piano was in the house

*The problem has good

reasons

*Nasty incidents have been recently

?A man with a dog is in the

garden.

Frequently, it is difficult to identify exactly what is wrong with a

learner's production because it 'just sounds wrong'. Avoidance of

the existential there clause is often the reason.

The other source of error with existential there sentences is

to neglect to note (or be told) that the subject must be indefinite.

For example:

We can have:

There's a girl in the classroom

but not:

*There's the girl in the classroom

unless the word there is an adverb of place

and

There's something I want to ask

but not

*There's that question I want to ask

(Note, however, that informally a definite noun phrase as the

subject is allowed:

There's my feelings to consider

There's Mrs. Smith who needs inviting.)

Concord with the existential there

Usually, in informal English, we assume that the dummy there is singular. This is not permitted in very formal English or anywhere near a grammar pedant. We can, therefore, have both:

- There's two men coming up the path.

- There are two men coming up the path.

The reason for this slight ambiguity is that, grammatically, there is the subject of the sentence but the subject of the 'normal' clause is notionally still the subject of the verb so both verb forms are allowable.

Relative pronoun clauses with existential there

This is a frequent pattern in English. For example

- There's nothing more (that) I want to see.

- There's nothing (which) interests me here.

(Note that in 15. it is possible to omit the relative which. That is not possible in other relative clauses because it is the subject of the verb.)

Other verbs with the existential there

The existential there is almost exclusively used with a form

of the verb be.

Up to now we have only been using there with the verb be

but there are other verbs which can be used. The copular verbs

seem and appear are obvious candidates but others are possible.

- There stood a suspicious-looking man on the corner.

- There appears to be a mistake in the figures

- There comes a time when I have simply to give up.

Uses like these are mostly literary and in 18., the clause has become a semi-fixed expression.

|

How many sorts of there clauses? |

Quirk et al (1972) identify six sorts of existential there sentence

forms. Others, e.g., Chalker (1984), refer to there used

this way as the introductory there without setting out the

possibilities in any detail and others, e.g., Parrott (2000) refer

to it as a dummy subject, again without setting out the

details. We'll follow the first of these in this list but reduce

the list to two main sorts, putting together related formulations

(because that's the way to teach them). The essential differences

are down to transitivity in English verbs.

This is not a teaching syllabus, of course, but teachers need to be

aware of the types of sentences in which the anticipatory, dummy or existential there occurs in

English because these are not paralleled across all languages and

present learners with some difficulties.

- Intransitive verbs

- There is / are + Subject + Verb

- There was a man waiting

- There was no-one looking

- Was anyone coming?

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Adverbial

- There was a frog in the pool

- There was nobody about

- Were there any people there?

- There is / are + Verb + Subject

Complement

- There is something unusual

- There isn't anything suspicious

- Is there something wrong?

- There is / are + Subject + Verb

- Transitive verbs

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Object

- There are three people asking questions

- There aren't any people eating the food

- Is there anyone ringing the bell?

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Object + Object

Complement

- There are some men working on the house

- There hasn't any work being done on it

- Are there any questions needing answers?

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Object +

Adverbial

- There is someone making a noise outside

- There were some children cleaning the playground up

- There have been lots of people photographing the lions in the zoo

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Direct

Object

- There is someone making the kitchen a mess

- There isn't anything to give you

- Is there anyone asking you questions?

- There is / are + Subject + Verb + Object

Adverbials and complements can, in fact, be tacked on to all the forms so we might get, for example:

- There is something unusual here

- There are three people asking questions loudly

- There hasn't any work being done on it yet

- There isn't anything in the cupboard to give the children to eat

There are, somewhat more rarely, passive possibilities with the existential there. For example:

- There will be no stone left unturned

- There have been four windows broken

|

it as a dummy or anticipatory subject |

The principles of end focus (old before new) and end weight are at work here, too.

The pronoun it can stand for complete clauses and is often

used in this way to allow us to shift the clause itself to the end.

This is why it is called the anticipatory it. The pronoun

anticipates what it stands for (often a nominalised clause).

We can convert a sentence with a nominalised clause to one with an

anticipatory it-subject like this:

To leave the party early was a mistake

becomes:

It was a mistake to leave the party early.

Try doing it in these examples and then click here.

- To leave India without seeing the Taj Mahal is crazy.

- That he is such a good cook is surprising.

- What I do or say to her doesn't make a difference.

- To hear him talking so rudely and callously shocked me.

More natural formulations might be:

- It is crazy to leave India without seeing the Taj Mahal.

- It is surprising that he is such a good cook.

- It doesn't make a difference what I do or say to her.

- It shocked me to hear him talking so rudely and callously.

The anticipatory it can also stand for a range of nominalised phrases and clauses as in, e.g.:

- adjective plus non-finite to-infinitive

- It is wonderful to

see her

It is a delight to watch

It's fun to try

It is a shame to miss the concert

It is a pity to lose the money

It is odd to forget them - adjective plus non-finite -ing clause

- It is lovely being here

It is horrible going shopping with her

It was nasty walking in the rain - nominalised finite that-clauses

- It is odd that she isn't here

It is a pity that she can't come

It is a shame that he's away

It as a dummy subject with no discernible meaning is used as the subject or object of many statements about weather, time, place and condition as well as some semi-fixed expressions. For example:

- It is raining

- It is Wednesday

- It would be nice if you helped

For a little more in this area, see the guide to nominal clauses, linked from the list at the end, in which the clause as the object or subject of a verb is discussed.

|

A note about other languages and teaching this area |

Very few languages handle this area in the same way that English

does. Few languages are as obsessed as English is with inserting a

dummy subject and in those languages, the subject is often simply

omitted, so you'll get errors such as

*I don't like when you call me

stupid

*I think is probable they will win etc.

Even if they do use a dummy it (as some do) they will probably

not use an existential form such as there.

For example,

There is a mouse in the house

might in other

languages be

It has a mouse in the house

It gives a mouse in the house

The

house has a mouse

It exists a mouse in the house

It finds a mouse in

the house

and so on.

Language such as Greek and Romanian which do not have a dummy subject of

any kind will often use a verb meaning exist so, directly

translating, speakers of those languages might produce

Exists a

mouse in the house.

Careful attention and alertness to your learners' production in this area pays dividends in terms of their being able to produce more natural sounding and less foreign utterances.

|

Awareness raising of the principles of end focus and end weight

|

It is probably worth a bit of classroom time to raise your learners' awareness of these two fundamental principles because they underlie so much which is otherwise hard to explain.

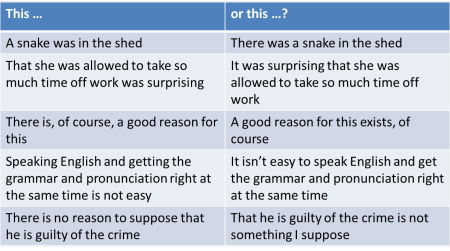

A straightforward way to start the process is to present the learners

with sentences which conform to the principles, contrasted with some

that don't but express the same meaning. For example, which of the

following are the most natural formulations? Click on the table

when you have an answer.

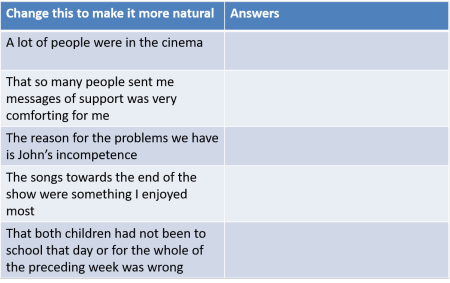

From there, it's a short step to getting learners to be able to

reformulate sentences more naturally as in this example. Click on

the table when you have the answer in your head.

| Related guides | |

| the word order map | for links to other guides in this area |

| cleft sentences | explaining how we get from, e.g., She liked the hotel to It was the hotel she liked |

| word ordering | for a guide to canonical and marked word ordering in English |

| fronting | for an analysis of how items may be marked and moved to the beginning of clauses |

| nominalised clauses | clauses acting as noun phrases are often the referent for the anticipatory it discussed above |

| theme and rheme | for more on how the anticipatory and existential uses of it and there form the themes |

| postponement and extrapositioning | which explains how and why items can be moved to the end of a clause or sentence |

References:

Bruno, C, n.d., Old Information before New Information, San

José State University Writing Center, at

http://www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter/ [accessed February 2015]

Chalker, S, 1984, Current English Grammar, Basingstoke:

Macmillan

Croft, W, 1990, Typology and Universals, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Parrott, M, 2000, Grammar for English Language Teachers (2nd

Edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Quirk, R, Greenbaum, S, Leech, G & Svartvik, J, 1972, A Grammar of

Contemporary English,

Harlow: Longman