Understanding speaking

|

What makes speaking difficult?

Many learners of English, when asked, will state that speaking is the hardest skill to master. It often is, and there are good reasons for this. Think for a moment about what makes speaking difficult. There are two sorts of factors at work: productive and social factors.

| Productive factors | Social factors |

| context dependent – what we say and how we say it depends on the context (where we are, what we are doing, who we are addressing etc.) | innovative – when we speak we often have to extemporise if, e.g., we can't find the right word or need a new concept |

| unplanned – unlike writing, we usually have very little time to plan what we are going to say (or no time at all) | informal – and often expected to be colloquial and idiomatic |

| transient – no record is kept (usually) of what we say so we can't backtrack very far to amend and adjust | rhetorical – speakers are often trying to inform, persuade or motivate (compare writing which is often used very logically and in an orderly way) |

| dynamic – speaking is interactional. What we say depends heavily on what is said to us. | inter-personal – we need to respond directly to our audience which may be sceptical, argumentative or downright hostile |

In what ways do you think these factors make speaking a difficult skill to master? When you have a few notes of what your initial reaction for each factor is, click here.

- context dependent

- speakers need to master competences to be able to speak

effectively in a range of settings. They need to have

discourse competence (e.g., know how to respond to an invitation)

sociolinguistic competence (knowing how to address people etc.) - strategic competence (when and what level of formality

is needed, when it is and isn't appropriate to say things etc.)

On top of all this, of course, speakers also need to produce language which is acceptably accurate structurally. They have to have linguistic competence. - unplanned

- time pressures mean that the amount of cognitive effort that is required to speak in a foreign language is very great and speakers often become tired and distracted quickly.

- transient

- although speakers can, and often do, backtrack to correct and repair interactions (with things like, No, that's not what I meant. I meant ... etc.) opportunities to do so are limited. (In written communication, we usually have the opportunity to re-read what we have written and make amendments for the sake of clarity, by contrast.)

- dynamic

- speakers have also to be listeners so skills are combined and misunderstanding what is said to you is often as fatal as saying the wrong thing altogether.

- innovative

- native speakers of all languages are adept at finding ways to make up for the speed at which they have to think so, e.g., in English we make adjectives vague (with, e.g., a bit / sort of / hard or coolish etc.) use generalised terms when we mislay a word (thingy, whatshisname etc.) or use circumlocution (e.g., it's the bit you need to make sure the juice doesn't spill over etc.). All of these things are difficult in a foreign language.

- informal

- learners of a language often sound overly formal and precise because they are trying hard to be accurate and orderly. Native speakers care less about these things because they have more resources and can be more innovative.

- rhetorical

- spoken language is often, for example, laden with modality (should, must, could, ought to, probably, certainly, if you get a mo' etc.) and such forms are difficult to deploy accurately in a foreign language.

- inter-personal

- picking up on the attitude of the person we are talking to and responding appropriately is something that native speakers do unconsciously, taking clues from body language, intonation, lexical choice and much else. That's hard to learn to do in a second language.

Add all these factors together and we get three major processing pressures:

- Time

- Preparation level

- Topic familiarity

and three main social pressures:

- Size of the audience

- Familiarity with the audience

- Roles of the people involved

|

Easing the pressure |

To help our learners, we need first of all to look at the ways that native speakers deal with all these issues. Here's how they do it:

| Processing pressures | Coping strategies |

| Time | Native speakers deal with

this pressure in a number of ways:

|

| Preparation level | Native speakers don't plan.

They are happy to string ideas together as they occur using

simple connectors like ... and ... and ... or ...

and then ... and then ... or ...so... so ... etc.

That's called parataxis. Speakers will also, more rarely, use what's called hypotaxis (The car over the road, The man I saw in the café etc. Listeners don't expect to hear well-formed, planned utterances in most cases. In this case, too, native speakers are happy to resort to colloquial and imprecise language and to simplification. One of the hallmarks of spoken language is that it is simpler than written language, both grammatically and lexically. False starts (He was with his friends ... Actually not all of them were his friends but anyway etc.) are common. |

| Topic familiarity | Native speakers are least at ease and least competent when talking about unfamiliar subjects so they tend to avoid them, keep quiet or speak more slowly with lots of fillers such as, Well, let me think, I'm not sure but .. etc. |

| Social pressures | Coping strategies |

| Audience size | If called on to speak to large numbers of people (and 'large' is a relative term), native speakers take opportunities to prepare what they will say carefully or use notes. |

| Familiarity with the audience | When speaking to people we don't know, native speakers often use more formal or neutral language, avoiding slang and colloquialism. They also say less. |

| Roles | When roles are equal or the speaker is in a superior role, speakers feel free to use all the tactics above to make speaking easier. When speaking to superiors, preparation is needed and a more formal tone adopted. |

|

Helping the listener |

Apart from helping themselves process and produce language under pressure, native speakers also help the listener in a number of ways in the effort to be clear. These include:

- substituting one word for another (That image ... er ... photograph over there is ...)

- repetition (The picture of ... the picture of the man and the woman ... with the woman in the background ...)

- reformulation (It's set in a large building ... like a warehouse or a hanger or something ... and there are ...)

- self-correction (I started to get on the train ... no, I was still on the platform, in fact, and I saw him ...)

|

Turn taking |

In addition to all this, speakers have a repertoire of ways to keep conversation moving along by signalling opportunities to take turns in speaking. There are five things that speakers have to know about turn taking (from Bygate 1987):

- Knowing how to show that you want to speak. This can involve noises or phrases (Hmm. Yes, but ...), gestures, intakes of breath and a number of other tactics.

- Recognising when to take a turn. Speakers often signal appropriate moments by assuming eye contact, falling voice volume or stopping and looking.

- How to hold one's turn by such techniques as starting with Well there are two things here ... or keeping the intonation up to show you haven't finished.

- Recognising other people's desire to take a turn (in other words, noticing the signals in 1., above).

- Knowing how to let them have a turn by gesture, look or phrase such as the use of question tags or straightforward questions.

There is a separate guide to turn-taking skills – covering what they are and how to teach them – on this site.

|

The structure of conversation: IRF sequences |

No analysis of speaking would be complete without some discussion of how conversation is structured. A simple but effective way of analysing this structure is to consider 3 main phases. The following is based on Tsui 1994:

- Initiation.

There are four ways to start a conversation:- Elicit (ask if). E.g., Have you eaten?

- Request (ask to). E.g., Can I ask you something?

- Direct (tell to). E.g., Pay attention to this; it's important.

- Inform (tell that). E.g., I noticed you didn't come to the meeting.

- Response

There are three types of response to an initiation. For example to the Initiation, Can you do me a favour? we can have:- Positive (preferred): Yes, sure, what can I do?

- Negative (dispreferred): Sorry, I need to go now.

- Temporising (dispreferred): Maybe. Will it take long?

- Follow up

There are also three sorts. Following from the three responses above, we can have:- Endorsement (positive). Great.

- Concession (negative outcome). Oh, I see.

- Acknowledgement (negative outcome). It's OK, I'll get John to help.

So we can have an analysis like this in the three 'moves' in a conversation:

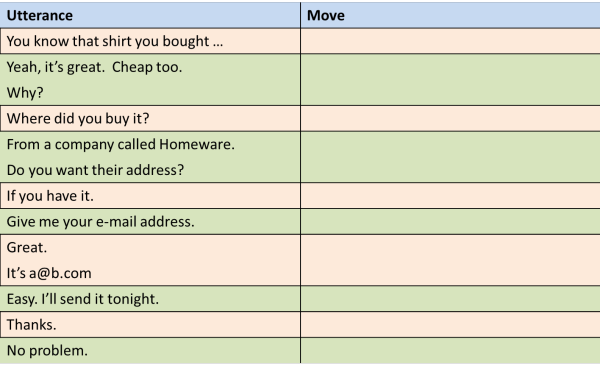

| Utterance | Move |

| Where did you buy your shirt? | Initiate: elicit |

| From a company called Homeware. | Respond: positive |

| Thank you. | Follow-up: positive outcome |

This is nice and simple but there's a problem. Real people just don't talk like this. Here's a more natural-sounding conversation. Can you do the analysis into I R F moves? Click on the table when you have.

Whether you got all that right or not doesn't matter too much now. What does matter is that you see why this conversation is more natural than the last one. Click here when you see it.

Right. Speakers conduct

two moves in their

turns. The second speaker responds with

Yeah, it's great.

Cheap too

but in the same turn starts a new

initiation with

Why?

This is the way many conversations

go.

One of the reasons that learners often say that native

speakers won't speak to them or that they find it hard to keep

conversations going is that they have failed to see that conversation

requires maintenance with new initiations in most response turns.

All the above is teachable but before we see how,

take a test to make sure you have understood.

From there, you can go on the guide to

teaching speaking.

References:

Bygate, M, 1987, Speaking. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Tsui, ABM, 1994, English

Conversation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Other references you may find helpful:

Brown, G & Yule, G, 1983, Teaching the Spoken Language,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bilbrough, N, 2007, Dialogue Activities: Exploring Spoken

Interaction in the Language Class, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

Hughes, R, 2002, Teaching and Researching Speaking, Harlow:

Longman

Luoma,

S, 2004, Assessing Speaking, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

Maley, A & Duff, A, 1982, Drama Techniques in Language Learning,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Porter Ladousse, G, 1987, Role Play, Oxford: Oxford University

Press

Rogerson, P. & Gilbert, JS, 1990, Speaking clearly: pronunciation

and listening comprehension for learners of English Student's Book,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press