Turn-taking

Turn-taking is an area of conversational analysis in which it may be defined as the study of the ways people take, use, construct and hand over turns in a conversation. Richards (1992: 68) describes turn-taking this way:

Conversation is a collaborative process.

A speaker does not say everything he or she wants to say in a single

utterance. Conversations progress as a series of “turns”; at

any moment, the speaker may become the listener.

(Richards, 1992:68)

It is important to be clear from the outset that turn-taking is

not the same as interrupting. In fact,

interruption per se is rare when people are speaking and

almost invariably seen as discourteous if not downright rude.

In general, Anglophone speakers do not talk over each other and do not break

inappropriately into other people's turns.

Turn-taking is also not the same as backchannelling which occurs

during a turn with the listener indicating interest, surprise,

encouragement and so on. There is a separate guide to

backchannelling linked in the list of related guides at the end, or you

can go to it now

(new tab).

What turn-taking does involve is the awareness of how to signal that

a turn is finished, how to show that one wants a turn and, having

got it, how to hold it.

In what follows we are analysing what is properly known as

discourse makers, i.e., those signals that speakers use to manage

and mark phases in discourse. Discourse markers are also part

of backchannelling language, of course.

The term discourse marker is now used so loosely in the profession,

to mean almost any language element that contributes to coherence or

cohesion that it has lost all utility as a technical term. We

shan't use it again here.

|

Culture |

This is an area very heavily influenced by considerations of

cultural appropriacy. What follows is an analysis of

turn-taking in some English-speaking (Anglophone) cultures but even within a

speech community (which for the English language as a whole is

around a third of a billion people) conventions will differ.

The main varieties of English in use as a first language include

American English, British English, Indian English, South African

English, Canadian English, Australian English, Irish English and New

Zealand English.

Other countries, including the Philippines, Jamaica and Nigeria,

also have millions of native speakers of English.

If we add in the number of people for whom English is a second

language (probably around a billion) using English in certain

settings such as for commercial, technical or administrational

purposes, the picture becomes even more blurred. When English

is employed as a second language, the surrounding cultural norms

concerning turn-taking may impose a structure wholly unlike cultures in

which English is used as a first language.

An important consideration in this area is the culturally determined

toleration of silence. Richards (op cit.) states, drawing on

Wardhaugh, that

A basic rule of conversation is that only one person speaks at a time, and in North American settings participants work to ensure that talk is continuous. Silence or long pauses are considered awkward and embarrassing, even though in other cultures this is not the case.

The pause length between turns that people will tolerate is closely aligned to cultural issues. In Anglophone countries, especially North America, pause length is kept as low as possible and the same applies, in general terms, to Greek, Spanish, Russian and many Arabic-speaking cultures. East Asian cultures, by contrast, tolerate and even expect inter-turn pauses to be considerably longer (Pöhaker, 1998:16).

Coulthard (1985: 55/56) also suggests, drawing on ethnographic research, for example, that:

French children are encouraged to be silent when visitors are present at dinner, Russian children are encouraged to talk.

They also report (op cit.) that Eskimos in Iceland may spend over an hour with neighbours during which there will be no more than half a dozen exchanges and that a typical feature of New York Jewish interaction is overlapping utterances which are intended to show enthusiasm and interest but which may show the exact opposite in other cultures, in which continual enthusiastic feedback may be viewed as a lack of attention and respect.

Additionally, there is evidence that within Anglophone cultures, silence on behalf of a participant in a conversation signals the need for someone else to take a turn and is not tolerated for long. In other cultures, such as those containing speakers of North American Athabaskan or Dene speakers (which includes, e.g., Navajo) silence betokens no such thing and speakers of these languages remain silent without this causing any feelings of discomfort.Encounters between English speakers and Athabaskan speakers may result, as Trudgill (2000:132) has suggested in

Athabaskans ... thinking that English speakers are rude, dominating, superior, smug and self centred

and English speakers finding

Athabaskans rude, superior, surly, taciturn and withdrawn

Applying the turn-taking rules of one's own culture when speaking a different language, especially to a native speaker, or to people who speak a different dialect of the same language is, therefore, fraught with danger.

Another important consideration in this area is the concept of power

distance because this is very variable across cultures. The

narrower the power distances between people, the more likely

interruption, talking over and maintaining a turn despite

interruption will be tolerated. In cultures with

conventionally large power distances handing over a turn may be

confined to those in authority and interruption or grabbing a turn

may be culturally disparaged.

Singapore, Hong Kong and India where there are millions of speakers

of English as a first language (often bilingually) have greater

cultural power distances than do countries such as The United

States, Britain, Australia, Canada and New Zealand with concomitant

intolerance by the more powerful of interruption by the less powerful

participants.

For more, see

the guide to learning style and culture and

the article on power distance and uncertainty avoidance, both linked

in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Transactions |

Turn-taking analysis is mostly concerned with interaction rather than transaction.

However, interactions often include transactional phases and transactions often include short interactions especially when the participants are known to each other. Whether this happens, and to what extent, is a culturally determined factor.

For example:

It is common in professional settings for the purpose of an exchange

is to achieve something for both parties so the overall intention is

transactional. However, it is rare for that to be all there is

and people who may know each other well in such settings will often

interleave purely interactional phases which are not concerned with

the business at hand but serve to oil the wheels of social

encounters.

In some cultures, most transactional events are preceded and

followed by some form of interaction and getting directly to the

point is often considered abrupt or even rude. In others, any

interactional language may seem odd and out of place in a

transaction. There is ample scope here for cross-cultural

misunderstanding, of course.

It is also common in what are on the face of things purely

transactional events such as service encounters for some

interactional language to be evident. In Britain, for example,

particularly when the participants are known to each other, it is

unusual not to find some interactional language, asking about

welfare, family and so on, to intrude into transactional events.

In other cultures, such an approach may be embarrassing and

unwelcome.

With regard to turn-taking skills, pure transactions are often

quite predictable because the customer rules the event. It is

the service provider's role to wait for a turn until invited to make

one by a question or statement, except for the ubiquitous use of,

e.g.,

How may I help you?

etc.

Turn-taking skills are important, nevertheless, whenever an interactional phase intrudes into the exchange.

|

Style and register |

Turn-taking is substantially affected by the nature of an

exchange. As we saw above, purely transactional exchanges

(such as many service encounters) do not require high-level

turn-taking skills. However, informal conversations are

another matter altogether.

The nature of informal conversation has been quite thoroughly

investigated and various authors have suggested what the defining

characteristics are of such encounters. Here, we will follow

Cook, 1989, who suggests the following five features:

- Informal conversation does not follow a set task. Neither side of such exchanges has a particular end in sight and no agenda is set. Compare this, for example, to a workplace meeting which may, indeed, be informal and require good turn-taking skills but which will also have some kind of agenda to follow and task to achieve, however vaguely that is defined. This is a register rather than a style issue but they are connected features.

- Power relationships tend to be fairly equal. If they are not, turn taking proceeds rather differently with one person nominating not only whose turn is next but also what the topic (and sometimes the content) of the turn will involve. Inequality in participation is often a feature of some registers – education, managerial, administrational etc.

- There is usually a small number of participants. Even in large gatherings, informal conversations tend to be in small groups of only two, three or four people. Anything larger and we are in the realms of speeches or plenary addresses which, apart for barracking from the floor, do not usually require any turn-taking tactics.

- Turns are short. Sometimes, in informal conversation, turns may even consist only of a single word or phrase. In more formal settings or those which have an agenda, turns are often quite long and turn-taking is determined by the particular interests and expertise concerning the field of individuals.

- The talk is intra-personal. Its purpose concerns the participants and it is not intended to be overheard or directed at a wider audience outside the participants. In some registers, the participants in the exchange may be confined to two or three people but they know that their contributions are being heard by and are, therefore, intended for, a wider, often silent audience.

So, depending which kind(s) of turn-taking skills you want to teach, develop and practise, you need to make sure that the context in which presentation and practice take place is in line with the kinds of skill you want to be the focus. Read on for more.

|

Setting |

The setting in which the language is being used will also be influential. In formal situations, such as business meetings,

lectures, committee meetings, press conferences, presentations and

so on, turn-taking may be rigidly controlled by a chair, the

presenter or the educator. In these settings, turn-taking will

be by invitation and one person will decide who speaks, when, on

what topic and for

how long.

In these circumstances, turn-taking skills are little needed because

the participant has no freedom to deploy them.

Chairing meetings and ensuring that turns are taken equitably is a

skill in itself requiring, inter alia:

- Ways of including quieter participants: e.g.

Fred. Do you have a view? - Ways of silencing the over-enthusiastic speaker: e.g.

Thanks, Jane. Let's get some other views now, huh? - Ways of keeping the conversation on track: e.g.

We are getting off the topic. Let's go back a bit. - Ways of moving things on: e.g.

Right, let's move on. - Ways of closing a topic: e.g.

Does anyone have anything to add before we move on?

If, naturally, one of the aims of your learners is to use their language skills in more formal work- or study-related registers, then both the ability to use the chairing skills and, perhaps more crucially, the ability to recognise the signals, is a skill worth teaching, developing and practising.

It is in less formal settings, such as conversations between equals, in small groups or pairs, that turn-taking skills come to the fore.

|

Turn-taking skills |

| Can I just say ... ? |

Bygate (1987: 39) identifies five skills that speakers need efficiently to manage conversations. It bears stating the rather obvious that both speakers need the skills if a conversation is to be successful in this regard. These skills are reciprocal. The ability to signal that you want a turn includes the ability to recognise such signals in others and signalling the end of your turn involves recognising such signals in others so the list may be reduced from five skills to three:

- Recognising the right moment to have a turn and signalling the end of your turn

- Knowing how to signal that you want to speak and recognising when others want to speak

- Resisting interruption: holding the floor

We could, following Thornbury (2005), add another skill and that

is signalling that you are listening but this does not only apply to

turn-taking, of course. Backchannelling is a skill that

applies during turns, not at the interface between turns.

There is little doubt that some back-channelling utterances can

develop into a turn-taking event because the speaker may perceive

them as signalling the wish to take a turn but they are not in and

of themselves, turn-taking devices.

Some backchannelling may also mean that the hearer has no wish to

take a turn but utterances such as

Uh, huh

Oh!

Dear me!

etc. are variously interpretable and unpredictable. They may

be encouragement to continue the turn or they may be signalling a

wish to take a turn. Much depends on the speaker's confidence

and intentions and the context. The current turn-holder's

confidence and intentions also play a role.

The guide to backchannelling, linked in the list of related guides at the end, has more.

It is by no means the case that native speakers are all equally proficient in these skills.

|

Recognising the right moment to have a turn and signalling the end of your turn |

There are several linguistic and paralinguistic ways in which we

recognise that it is appropriate to take a turn in a conversation.

The key in English is recognising completion or, better,

potential completion.

This is also known in the literature as a transition-relevance point

or TRP (Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson, 1974).

Taking turns smoothly depends on recognising a suitable TRP.

The current speaker may, and often does, signal the completion of a thought or sentence by taking control not only over who speaks next but what they say. This is done in three ways:

- Selection and constraint

- A speaker may select the next person to take a turn, either

by naming them or by alluding to them in some way. For

example:

What do you say, John?

Well, we have an expert here, don't we?

What do those who actually live there think?

etc.

In this case, the next speaker has often been constrained in terms of the form of his or her turn by what the current speaker says.

It may be the case that the current speaker produces the first item of an adjacency pair such as:

I'm sorry if I've gone on about it (an apology)

followed by the next speaker's

That's OK, it's important to you (expressing forgiveness)

Selection may also be achieved through gaze, i.e., selecting the next to speak by making eye contact with them. See below on more about eye contact. - Constraint

- A speaker may signal the end of a turn by constraining the

form of the next utterance but not selecting a speaker to

perform it. For example,

Does anyone know what time it goes?

constrains the next utterance to the expression of information or the expression of ignorance. Who actually speaks has not been selected unless, of course, there are only two participants, in which case, the formulation would be

Do you know what time it goes?

Tag questions are frequently used in this respect. For example:

It's a disgrace, isn't it↘?

with falling intonation inviting the next turn to be an agreement

I thought it was awful, didn't you↗?

with rising intonation signalling that the next turn will be an expression of opinion one way or the other. - Open-ended turn passing

- A speaker may do neither of the above and simply signal the

fact that his or her turn has finished by falling silent,

finishing with falling intonation or shifting gaze.

In this case, it is up to the other participant(s) to self-select who is going to continue the interaction and the direction in which it will go.

Interestingly, these three turn-passing mechanisms come in order

of precedence. If a speaker has selected who is to take the

next turn, that is the person who will speak next. If someone

else takes the turn instead, participants will often see it as inappropriate

and take steps to repair the interaction with statements such as

Yes, what do you

think, Mary?

If a

speaker has constrained the type of utterance that the next turn

will be, that is what happens, whoever speaks next. If there

are no constraints and no selection, anyone can speak next and

perform any chosen function.

All of this is premised on the ability of listeners to identify potential completion. How they do this is slightly mysterious but some commonalties are discernible.

- Predicted sentence completion

- Listeners are often able to predict with fair accuracy how a

sentence will finish so for example:

A: Sorry we are as bit late, the traffic was

B: Awful, yes it always is on Fridays - Assumed sentence completion

- Speakers may also select the correct moment to intervene

when they identify a place in the previous speaker's utterance

where they can insert their own view of the facts. This is

a syntactical skill of recognising when a clause is complete. This

may often occur after subordinating conjunctions because the

type of conjunction usually signals the type of subordinate

clause which will follow. For example:

A: I didn't speak to her because, erm↘ (falling pitch and volume)

B: she was too busy. Yes, she often is, isn't she?

(Coulthard (op cit.: 64)) reports that in one study, it was found that 28% of all interruptions occurred after a conjunction.)

However, if the subordinating conjunction is stressed and spoken with a higher pitch, that is a signal that the speaker wishes to maintain the turn as in, e.g.:

I haven't done that yet because ↗ ... (rising pitch and volume)

Speakers may also take over a turn and insert their own subordinating conjunction such as:

A: I'd met her, actually, erm

B: before the meeting. - Silences

- Sometimes, speakers may simply fall silent to signal completion. If no subsequent speaker starts almost immediately, the speaker may take up the turn again. In most cases, however, because silence is to be avoided, another speaker will almost always take a turn.

- Intonation, pace and pitch

- According to Brazil (1997), speakers may signal the end of a

turn by:

Slowing down

Speaking more quietly

Lowering the voice pitch

This is not a trivial matter as people who have deliberately altered their voice tone to sound more serious and less strident have discovered. A classic example, described in some technical detail by Beattie, Cutler and Pearson (1982) is the then British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher's, attempt to sound less shrill and hysterical by lowering her voice tone and pitch. The result was that she inadvertently sent turn-passing signals to interviewers who, predictably, interrupted her much more often.

|

Knowing how to signal that you want to speak and recognising when others want to speak |

If the previous speaker has selected the next, signalling that

you want to speak is, naturally, unnecessary. However, in

other cases, such signals are very important.

Providing that you have correctly identified a potential or actual

completion, there are a number of ways of doing this and starting

your turn.

- Initiation

- Speakers can, at the clear end of someone else's turn,

simply start a new direction with expressions such as:

Well, let me straight away tell you what I think

I can't agree with much of that because ...

etc.

Initiations like these rarely form interruptions and usually come when an end-of-turn signal has been sent. - Interruption

- As we have seen interruptions are often in the form of

predicted or assumed sentence completions but they needn't be.

However, they still need to be timed correctly at potential

completion points because they otherwise appear rude and

discourteous. They need to be carefully hedged and

produced with the correct intonation, usually a fall-rise

pattern, if they are not to offend. For example:

Before you go ↘ on ↗ ...

Could I just ↘ say ↗ ...

It's important to distinguish between interruptions and interjections. The former acts as the opening of a new turn, the latter may just be a momentary insertion into someone else's turn and a form of back-channelling. For example:

Oh, yes, that's true

interjection, after which the speaker will simply continue

Now stop right there

interruption, at which point the speaker may hand over the turn or resist the interruption (see below). - Topic shifting

- By topic shifting is not meant a total change in topic as

that is quite a rare event. We do not, for example,

frequently shift a topic from, say, gardening to travelling by

train. Usually what is meant is signalling a desire to

follow a parallel or associated idea.

The topic shifters' reasons may be that the subject appears to have run its course, that they feel unable to contribute anything further or that they will be more comfortable if the conversation took a slightly different turn. Whatever the reason for topic shifting, timing is important if discourtesy is to be avoided so there is a need to listen out for potential utterance completions.

There are a number of prefabricated chunks of language which native speakers deploy as single items to achieve topic shifting and they include a range of conjunct expressions, for example:

Another popular topic shifting device is to use questioning, such as:So, ...

That reminds me.

Speaking of which ...

Talking about ...

On that note, ...

Oh, before I forget ...

I’ve just remembered ...By the way, ...

Anyway, …

That reminds me …

Oh, I wanted to tell you …

Funny you should mention that …

Come to think of it ...

It occurs to me that ...

So, what do you do instead?

And then what happened?

How did you feel?

etc.

Occasionally, an event may occur in which the topic is shifted completely from the conversation up to then. Cook calls this a side sequence and others have similar names for the phenomenon. For example:

A: So, I spoke to her about getting more training and ...

B: Gosh, is that my train already?

A: No, that's the Brighton train. As I was saying, ...

When side-sequences occur, the first speaker nearly always recaptures the turn with a prefabricated phrase or clause such as:

As I was saying ↗

Well, anyway ↗

etc.

Even when the topic shift has not been so extreme, speakers may wish to recapture the turn and go back to the thread with similar expressions.

Intonation and stressing are important:- Almost all these expressions and the questions will have a quite noticeable rising intonation contour because they are incomplete utterances and the speaker will want to resist interruption until an extra thought is added.

- As is usual, word stress will fall on the content words, reminds, talking, forget, remembered, tell etc.

- Because these are prefabricated chunks of language, they are

often spoken quickly with marked phoneme reduction and weakened

forms so, for example,

Come to think of it

As I was saying

may be pronounced as: /kʌm.tə.ˈθɪŋ.əv.ɪʔ/ ↗ or as /əz.aɪ.wəz.ˈseɪ.ɪŋ/ ↗ respectively with elided phonemes and weak forms, especially the schwa, and a rise in intonation at the end signalling a follow-up.

- Paralinguistic signals

- Although culturally variable (and quite possibly perilous to

experiment with)

such signals include:

taking a sharp intake of breath

leaning forward

raising a finger or hand

shaking your head

shaking your hand side to side

exclamations such as Ha!, Whoa!, Ah, ha!

etc.

|

Resisting interruption: holding the floor |

Even when a listener has recognised a potential completion, or Transition Relevance Point, it is possible for a speaker to resist interruption and we can do this in a number of ways:

- Intonation, pace and pitch

- Slowing down, speaking more quietly and lowering voice pitch

are all ways of signalling the end of a turn so

Speeding up

Speaking more loudly

Raising the voice pitch

are all ways of resisting interruption. Doing the opposite, as Margaret Thatcher discovered, invites rather than resists interruption. - Referring explicitly to the interruption

- Speakers may resist interruption by referring to the fact that it has been attempted. For example:

If I might just finish

Let me finish

No, I want to make this point

Just a moment, please

etc. all in response to an attempted interruption.

- Incompletion markers

- It is possible for speakers to insert markers (often

subordinating conjunctions) to signal that a thought is

incomplete. Usually, these must be emphasised and produced

with a rising rather than falling intonation. For example:

I may be wrong but ↗ ...

The situation will get worse because ↗ ...

This is an unsophisticated approach because, as we saw, such conjunctions may be heard as potential completions and invite interruption through predicted sentence completion. Syntax may override intonation in this case. - Initial markers

- A slightly more sophisticated approach is to place the

conjunction at the beginning of the utterance and to use a

rising tone on the last element of the clause in, e.g.:

Because there is such uncertainty ↗ ...

If the situation goes on like this ↗ ...

because this makes it more difficult for people to assume or predict the completing thought. - Pre-structuring

- Speakers can signal in advance when a turn will finish by

pre-structuring signals such as:

I need to say two things here ...

Firstly, ...

There are two obvious problems

etc.

Pre-structuring acts make it much more difficult for interruptions to occur until both (or all three etc.) points have been made. If you listen to an experienced politician being interviewed, you'll see how effective this technique can be. Here's an example from Coulthard (op cit.: 64):Now I think one can see several major areas here ... there's first the question ... now the second big area of course is the question of how you handle incomes and I myself believe that we have to establish in Britain two fundamental principles. First of all ...

(Denis Healey: Analysis, BBC Radio 4) - Fluency

- The fewer the uses of hesitations and fillers such as

erm, well, y'know, like etc. the less vulnerable the

speaker is to interruption.

Fluency can be maintained, however, by the use of prefabricated fillers spoken quite loudly with rising tones such as:

Well, let me think for a minute

My own opinion is ...

Let me make this clear

etc.

For more on hesitation and filler phenomena, see the guide to communicative strategies and tactics, linked below.

|

Adjacency pairs and constraints on speakers |

We have seen above that a turn may be constrained by speaker and

topic, topic only or unconstrained in any way.

There is, however, another way conversation is structured which also

constrains the next turn very precisely and it concerns adjacency

pairs. There is a guide devoted to this topic, linked below,

so we will be brief here.

The guide to adjacency pairs includes this example of two of them in

a small dialogue with the first adjacency pair

in red and the

second in black:

| Speaker | Utterance | Description |

| George | Hello, Peter. How are you? | Formulaic greeting |

| Peter | Oh, hi. Fine, thanks | Formulaic greeting response |

| George | Has Mary got in yet? | Request for information |

| Peter | I think so. | Preferred provision of information |

For more, see the guide to the area which contains a long list of possible adjacency pairs in English.

Adjacency pairs have four important characteristics (Schegloff and Sacks (1973)):

- adjacent

That is to say they follow each other directly in conversational exchanges. Turn 1 must be followed, therefore, by Turn 2 with no intervening turns. - produced by different speakers

so are an essential part of turn taking. Recognising the function of the first part of an adjacency pair is critical to knowing when and whether to take a turn and what the content of the turn should be.

When speakers have produced the first item in a pair, they usually fall silent (a central indication of turn passing) and wait for the second part to appear in the exchange. - ordered

in that it is usually (not always) possible to detect which of the pair precedes the other, i.e., which is the first and which the second part of an exchange. - typed

so the first part requires (or usually evinces) a particular sort of second part rather than it being a randomly generated utterance. This is key to the constraint principle with which we are concerned here.

The point concerning turn-taking skills is the last

characteristic in that set: adjacency pairs are typed and that means

that the first part of the pair constrains the second part very

precisely. When a speaker does not hear, misinterprets or

ignores this simple fact, conversation and turn taking break down,

sometimes almost irretrievably.

Here's an example of what happens when adjacency pairings are

recognised and acted on conventionally.

| Speaker | Turn | Description |

| George | The dog hasn't been fed | A directive masquerading as

information giving. The speaker is supplying information but asking for action. |

| Peter | I know, I'm just doing it. | A response accepting responsibility and confirming an action. |

| and here is what happens when the second turn-taker misinterprets what the content of the turn ought to be: | ||

| Speaker | Turn | Description |

| George | The dog hasn't been fed | A directive masquerading as

information giving. The speaker is supplying information but asking for action. |

| Peter | Oh, hasn't she? | A response which wrongly assumes

that the first turn was simply providing information. This is an appropriate response to the provision of information but that is not in fact what the first turn was doing. |

The moral is that in order to take a turn conventionally and not

disturb the flow of an exchange, it is vital to recognise the

communicative (or illocutionary) force of the previous turn.

Speakers may recognise that a turn is required because the other

speaker has fallen silent but, unless they are aware of the

intention of the first turn, they will not recognise the constraints

concerning the appropriate content of the second turn.

The second illustrative conversation above will need be repaired

with something like:

George: Well, will you

feed her, please?

which may be followed by:

Peter: Oh, sorry.

Yes.

It is also the case, incidentally, that adjacency pairs are, to

some extent, culturally determined. For example, in some

cultures and settings, the transmission of information such as:

The work isn't finished

will evince a simple:

Yes, I know

but in other settings and cultures it may well require:

I am very sorry and will do better

See below for a little more on how to alert learners to the

culturally determined nature of adjacency.

|

Seeing eye to eye |

The meaning of eye contact (or gaze) is subject to a good deal of pop psychology. Here are some myths about making or breaking eye contact:

- Avoiding eye contact is a sign of lying or deception

- Maintaining eye contact is a signal of focusing on what someone is saying

- Breaking eye contact invites a turn

- If maintained too long, eye contact is always a sign of aggression

Within the pseudo-science of Neuro Linguistic Programming, incidentally, much is made of the important of eye movements. It is, for example, averred that looking upwards signals that a person is using visual thinking, side-to-side movements indicate auditory thinking and downwards movements indicate kinaesthetic thinking.

These are myths, not facts.

|

Culture |

There is ample evidence that holding someone's gaze means

different things in different cultures.

Specifically, in the western world, which is home to most Anglophone

nations, holding eye contact with the person you are speaking to can

be seen as a positive signal of interest and rapport. In many

East Asian cultures, on the other hand, maintained eye contact may be seen as

discourteous and even threatening.

Setting will, naturally, play a role here, too. In western

cultures, in conflictual settings, eye contact may be seen as

assertive, even aggressive and in Eastern cultures, holding eye

contact with people of a higher status (such as managers, teachers,

elders and so on) may be regarded as discourteous and impertinent but with people of

equal status, as friendly and rapport building.

The reasons for the differences are obscure but there is some

evidence that it is to do with the way members of different cultures

use facial recognition skills.

There are implications here for teachers, of course, especially if

the teacher and the learners are representatives of different

cultures with different expectations of what is appropriate in this

regard.

|

Cognition |

In police dramas on TV and the like, it is popularly assumed that

someone who won't hold your gaze when speaking to you is being

deceptive and mendacious. To debunk this myth, try a small

experiment:

Ask someone to do a challenging mental task such as naming all the

fruits they know in any foreign language or listing the keys on the

bottom row of a computer keyboard. As they do the task, watch

their eyes. In most cases, people will break eye contact

immediately because it has been shown that the ability to do tasks

like this is impaired if the subject is also required to maintain

eye contact. To demonstrate this, ask the person to do a

similar challenging task but require them to hold eye contact with

you while they do it. It will be unusual if they do not find

the task more difficult in these circumstances.

There is also evidence that very easy tasks may be accomplished

while maintaining eye contact and very difficult tasks will also

allow the subject to maintain eye contact because they have,

effectively, given up and are not doing anything at all. For

more, see Doherty-Sneddon, 2019.

The moral for teachers is, of course, not to assume that lack of eye

contact means that the learner is not attending. They are more

likely to be thinking hard.

|

Eye contact |

When it comes to turn-taking, eye contact also plays a role but

not, sometimes, the one you may think. It is often averred

that breaking eye contact means giving up a turn but that may not be

the case.

When someone is thinking hard, for example, when trying to recall a

sequence of events or explain a complicated procedure, they may well

break eye contact to focus on the mental task of reconstruction.

When that is done, eye contact may be re-established and that will

signal something like:

OK. I have done the task. What do you say?

Initiating eye contact in this case signals giving up the turn, not

maintaining it.

|

Teaching turn-taking skills |

There are poor ways to do this:

- To ignore the area and assume that these skills will somehow

be absorbed or transferred from the learners' first

languages(s).

There are associated problems with this:- Skills like this, especially in terms of the language which is used will only be absorbed if the learners are exposed to and required to notice the language and techniques.

- We saw above that turn-taking is an area in which the learners' cultures play a hugely significant role. Not to teach how turn-taking is accomplished in Anglophone environments is a serious omission for learners who will need to operate in those settings.

- We have seen above just how often turn taking, retrieving and turn offering signals consist of prefabricated language chunks which do not need to be processed word by word. Learners need consistent exposure and lots of practice to automatise the language so that they are not hunting for lexis and constructing syntax from scratch when they are engaged in any kind of interaction.

- To confuse turn-taking with backchannelling. Although there is undoubtedly some overlap between these two types of discourse marker, they are distinct categories. Conflating them leads to bewilderment and the inducing of error in the learners' production and ability to handle conversational language.

- To teach the language without teaching the purposes for

which the language is used. This generally decays into a

kind of phrase-book approach in which learners are given

dubiously useful sets of language exponents but are not able to use

them appropriately because the setting and purposes have not been made clear.

- While it is useful to have a set of language chunks at

one's disposal, some of the following are not used for

turn-taking per se but to introduce a speaker's

turn, re-start a turn or simply indicate interest (i.e.,

backchannelling).

Using them inappropriately as turn-grabbers may often be considered rude. Knowing how to use them appropriately, on the other hand, is a real aid to fluency because they are prefabricated and do not need to be constructed from scratch. There's more on this at the end of this guide under teaching ideas. - Sets of exponents might include, for example:

- that reminds me (= I am continuing the same topic and starting my turn)

- by the way (= I am indicating a topic change and starting my turn)

- well anyway (= I am returning to the topic and re-starting my turn after an interruption)

- like I say (= I am repeating what I said before and re-starting my turn after an interruption)

- yes, but (= I am indicating a difference of opinion and trying to take a turn)

- yes, no, I know (= I am indicating agreement with a negative idea and interjecting rather than interrupting)

- uh-huh (= I am listening and I don't want a

turn)

(based on Thornbury, op cit.)

- While it is useful to have a set of language chunks at

one's disposal, some of the following are not used for

turn-taking per se but to introduce a speaker's

turn, re-start a turn or simply indicate interest (i.e.,

backchannelling).

|

Awareness raising |

Many learners (and not a few teachers) are unaware how and to

what extent cultures differ in this area. Before we can begin

to teach the area, learners need to be convinced that there is

something worth learning.

A little cross-cultural awareness-raising is called for.

In mono-cultural settings with all the learners from the same

culture, especially if the teacher shares awareness of the culture's

norms, this is comparatively straightforward because we only need to

tackle the differences between two cultures.

In more diverse settings, the situation is more complex, albeit more

interesting as well.

Guessing games are a way of doing this. For example, a simple

questionnaire to discuss in pairs or small groups (putting learners

who share cultures into the same groups) can work well. Like

this:

| In your culture, can you interrupt? | Yes | No | Sometimes |

| In a formal business meeting | |||

| When chatting with friends | |||

| Talking to your friend's father | |||

| At a dinner party | |||

| In a school classroom | |||

| When someone is telling a story | |||

| When someone is giving a speech | |||

| When your boss is explaining something | |||

| In a television interview | |||

| When your mother is giving you advice | |||

| When someone is giving you directions |

How you approach this and what the settings are will vary, of

course. One way is to get people to fill in the grid

individually and then get them to explain their choices to a friend.

Alternatively, you can discuss the outcomes as a whole class,

focusing especially on what prompts a 'sometimes' answer. For

example, it may be OK to interrupt a colleague in a business meeting

but not your superior. It may also be in order to interrupt a

classmate but not the teacher.

The next step is to run the same exercise but focus on what is

acceptable in an Anglophone environment such as Britain, Australia

or the USA.

The answers may well surprise people.

|

Keeping things distinct |

You cannot hope to teach all the subskills and techniques

concerned with turn-taking in a single lesson or short series of

lessons.

You need, therefore, to look at the analysis above and take one area

at a time. A good place to start is with identifying when

speakers want to pass a turn and how they signal completion.

They may do this in a number of ways (see the analysis above).

Almost any good coursebook will come with a few dialogues either

audio or video recorded and these can be mined for examples of how

people signal the ends of turns.

If you don't have this kind of resource, it is not difficult to make

a recording of two or more speakers passing the turns in a

conversation. Any recording you make should show examples of

- silences

- pausing after (or before) conjunctions (i.e., syntactical signals)

- slowing down

- lowering voice tone

- lowering voice volume

Once people have recognised where to interrupt and take a turn you

can go on to suggesting how to take up a turn (sentence completion, new initiation

etc.). It is not possible to do that until you have made the

learners aware of when to take a turn, of course.

Once they do know how to recognise the appropriate moment to start

their turn, you can get into the phrase-book teaching of terms such

as

That reminds me↗ ...

Yes, but↗

...

I know, awful isn't it?

and so on.

All of these sorts of expressions are useful but only if you know

when to deploy them and how to say them.

For example, using a backchannelling device as a turn grabber will

often result in some breakdown in rapport if not communication.

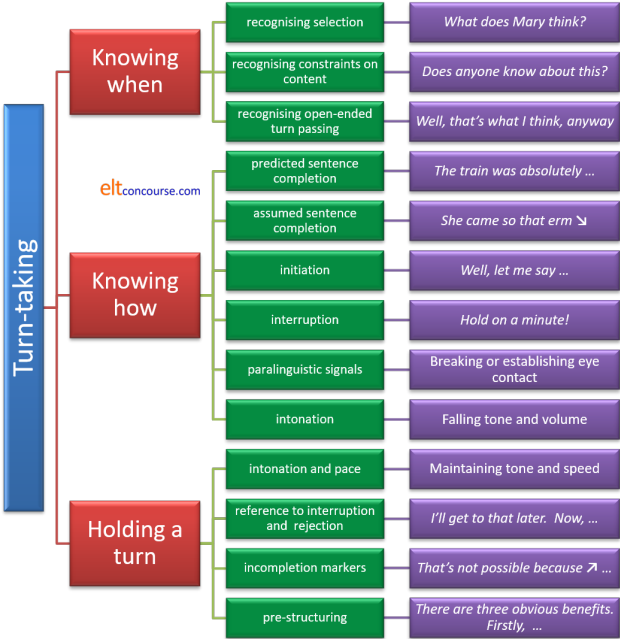

In summary, a teaching programme could usefully be divided into distinct areas such as:

- Knowing when:

- recognising selection

- recognising constraints on turn content and function (adjacency pairs)

- recognising open-ended turn passing

- Knowing how

- predicted sentence completion

- assumed sentence completion

- initiation

- interruption

- paralinguistic signals

- intonation

- Holding the floor

- intonation and pace

- reference to the interruption and its rejection

- incompletion markers

- initial markers (usually subordinating conjunctions placed at the beginning of a sentence)

- pre-structuring

If you prefer a diagram:

The content of the fourth column is exemplification only. There are lots of other ways of doing this.

|

Some ideas |

Recognising selection and constraints

For awareness raising of selection and constraints on the function of the next turn:

| Choose the 'correct' turn |

|

||

| 1 | Peter: What do you think, John? | Mary: Great idea! | |

| John: What should we do? | |||

| John: I'm not too sure it'll work | |||

| John: Where's Fred? | |||

| 2 | Mary: ... and then we came home to get warm | John: I can imagine you needed to | |

| Peter: As I was saying ... | |||

| Jane: Why? | |||

| 3 | Jane: We couldn't fit the sofa in the car ... | Peter: So they called me, of course | |

| Mary: I know how you feel | |||

| John: That reminds me of a time in America | |||

Step two is to use prompts such as the ones in this little

exercise to get learners to produce rather than just recognise the

appropriate speaker and the appropriate corresponding function.

That can be done either as a whole-class exercise with the teacher

providing the correct falling intonation or pauses or / then in

small groups equipped with prompt cards.

Predicting or assuming sentence completion

This can be tackled in a similar way by setting up exercises for learners to recognise the appropriate sentence completion (often with utterances finishing with a conjunction of some kind). Like this, perhaps:

| What's the next turn? |

|

||

| 1 | Peter: So we had to stop because, erm, ... | Mary: It had got too dark, hadn't it? | |

| John: So what did you do? | |||

| Jane: How awful! | |||

| Jim: Why? | |||

| 2 | Mary: We took him to the hospital then, erm, ... | Jane: Why? | |

| Peter: As I was saying ... | |||

| John: And was he OK? | |||

| 3 | Jane: They couldn't give me my money back, of course, ... | Peter: So what happened then? | |

| Mary: Because you'd worn them, right? | |||

| John: I had the same problem | |||

Again, after learners can recognise the correct predicted or

assumed sentence completion, they can go on to providing one for

prompts either from the teacher or from their classmates.

You'll need to practise the paralinguistic features associated with

being prepared to give up your turn to do this successfully before

you ask the learners to dive in to an exercise.

Paralinguistic features

These need first to be demonstrated either through a video (TV soap operas are a good source) or via the teacher. Again, focus is important so that the cultural appropriacy of each feature and how it is performed can be learnt. You need to focus on the features identified above, i.e.:

- taking a sharp intake of breath

- leaning forward

- raising a finger or hand

- shaking your head

- shaking your hand side to side

- exclamations such as Ha!, Whoa!, Ah, ha!

but not all at once!

Practising these can be fun and getting learners to act out short

dialogues they have written containing three of them at least can be

productive and engaging.

Holding the floor

This is a complex skill so needs to be broken down carefully into

the five or so techniques analysed in this guide. It is also a

culturally determined issue because many learners, from cultures

more polite and deferential than Anglophone nations, may be unaware

of the need even to have a technique or two.

As above, teaching in this area can proceed from recognition (by

demonstration) to practice (with one learner having to reject

interruption, override it or pre-structure a turn to avoid it

happening).

Getting learners to prepare and then deliver short presentations is

one way and another is the retailing of anecdotes and/or describing

something, someone or somewhere they know well while others try to

interrupt or spot potential completion points.

It can be engaging and productive but needs careful preparation and

planning.

Some training in the use of prefabricated fillers is also helpful

because, as we saw above, they can be deployed to gain thinking time

and resist interruption. Silence while a speaker thinks is

often, in Anglophone societies, interpreted as a turn-passing signal

and interruption will naturally follow.

|

Matching language form to function |

Sooner or later, of course, you are going to have to teach the

language that people need when taking turns or holding the floor.

As was noted above, ready-made, prefabricated chunks of language

are great aids to fluency. Inappropriately used, they are

tantamount to worse than useless.

It pays, therefore, to focus on some simple areas of turn-taking and

introduce, present and practise only the language that applies to

the particular function the speaker wants to perform.

Here are a few ideas:

|

I want to add something or ask something (and then you can go on):Can I just add that ...?Can I ask why / what / when / how etc.? May / Can I ask a question here? |

|

I want to hold on to my turn (I'll give it up when I have finished):I need to say two things ...There are two points here ... Although it was a nice idea, ... And what's more ... Let me make this clear ... |

|

I want to restart my turn after an interruption:As I was saying ...Anyway ... Be that as it may ... Now, where was I? |

|

I am giving up my turn voluntarily:Don't you think so?Go ahead. Yes, sure. Is that how you feel? |

|

I am giving back the turn to the last speaker:Sorry. What were you saying?As you were saying, I think. But you were saying ... |

It is simple to see how grids like that can be turned into awareness-raising, matching exercises and tasks.

|

Familiarity |

Turn-taking skills are not an easy set of skills and techniques

to learn so we need to make sure that the setting and topic are

familiar to the learners so that they have the cognitive space to

focus on the skill they are using, not the language they need to

deploy in the interaction. Maintaining fluency, for example,

in an attempt to hold the floor can best be practised in a topic

area in which the learner is comfortable operating.

A simple way to do this is to set the practice in a topic area that

the learners are familiar with and will have little difficulty

speaking to each other about. Topics might include, therefore,

an area which has recently been taught, personal anecdotes, giving

opinions about everyday matters and so on.

We are not, for the most part, teaching the language exponents of

interrupting and so on. There is no reliable list of exponents and unwelcome interruption

is, in any case, a rare turn-taking technique. Here we

are focused on a skill and on cultural awareness.

| Related guides | |

| speaking | where you will find more on some of aspects of analysing and teaching the skill |

| adjacency pairs | for a short guide to what they are and how we use them |

| context | what it is, where it comes from and face-threatening acts |

| discourse | the in-service index to more guides in this general area |

| backchannelling | to see where the differences lie in related areas of analysis |

| communicative strategies and tactics | for more on a range of the ways in which conversations are managed |

| learning style and culture | for more on cultural aspects of language use and links to articles about culture |

| articles | the link to the articles index |

References:

Beattie, GW, Cutler, A & Pearson, M, 1982, Why is Mrs Thatcher

interrupted so often?, Nature, volume 300, pages 744–747

Blais, C, Jack, RE, Scheepers, C, Fiset, D & Caldara, R, 2008,

Culture Shapes How We Look at Faces, available at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003022

Brazil, D, 1997, The communicative value of intonation in

English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bygate, M, 1987, Speaking, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cook, G, 1989, Discourse, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Coulthard, M, 1985, An Introduction to Discourse Analysis,

Harlow: Longman

Couto, I, no date, Turn-taking: whose turn is it anyway?

available at

http://www.luizotaviobarros.com/2012/02/turn-taking.html [accessed

July 2017] There are some other neat ideas there.

Doherty-Sneddon, G, 2019, Our visual experience: perception of

colour and eye contact, BBC radio interview, available at

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0004slk

Pöhaker, K, 1998, Turn-taking and Gambits in Intercultural

Communication, Graz, Austria: Karl-Franzens-Universität

Richards, JC, 1992, The Language Teaching Matrix,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sacks H, Schegloff EA, and Jefferson G, 1974, A Simplest

Systematics for the organisation of turn-taking for conversation,

Language, Vol. 50, No. 4, Part 1, pp. 696-735

Schegloff, EA & Sacks, H, 1973, Opening up closings,

Semiotica, 7 (4), 289-327

Thornbury, S, 2005, How to teach Speaking, Harlow: Longman

Trudgill, P, 2000, Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language

and Society, London: Penguin Books