Understanding speaking

|

What makes speaking difficult?

Many learners of English, when asked, will state that speaking is the hardest skill to master. It often is, and there are good reasons for this. Think for a moment about what makes speaking difficult. There are two sorts of factors at work: productive and social factors.

| Productive factors | Social factors |

| context dependent – what we say and how we say it depends on the context (where we are, what we are doing, who we are addressing etc.) | innovative – when we speak we often have to extemporise if, e.g., we can't find the right word or need a new concept |

| unplanned – unlike writing, we usually have very little time to plan what we are going to say (or no time at all) | informal – and often expected to be colloquial and idiomatic |

| transient – no record is kept (usually) of what we say so we can't backtrack very far to amend and adjust | rhetorical – speakers are often trying to inform, persuade or motivate (compare writing which is often used very logically and in an orderly way) |

| dynamic – speaking is interactional. What we say depends heavily on what is said to us | inter-personal – we need to respond directly to our audience which may be sceptical, argumentative or downright hostile |

In what ways do you think these factors make speaking a difficult skill to master? When you have a few notes of what your initial reaction for each factor is, click here.

- context dependent

- speakers need to master competences to be able to speak

effectively in a range of settings. They need to have

discourse competence (e.g., know how to respond to an invitation)

sociolinguistic competence (knowing how to address people etc.) - strategic competence (when and what level of formality

is needed, when it is and isn't appropriate to say things etc.)

On top of all this, of course, speakers also need to produce language which is acceptably accurate structurally. They have to have linguistic competence. - unplanned

- time pressures mean that the amount of cognitive effort that is required to speak in a foreign language is very great and speakers often become tired and distracted quickly.

- transient

- although speakers can, and often do, backtrack to correct and repair interactions (with things like, No, that's not what I meant. I meant ... etc.) opportunities to do so are limited. (In written communication, we usually have the opportunity to re-read what we have written and make amendments for the sake of clarity, by contrast.)

- dynamic

- speakers have also to be listeners so skills are combined and misunderstanding what is said to you is often as fatal as saying the wrong thing altogether.

- innovative

- native speakers of all languages are adept at finding ways to make up for the speed at which they have to think so, e.g., in English we make adjectives vague (with, e.g., a bit / sort of / hard or coolish etc.) use generalised terms when we mislay a word (thingy, whatshisname etc.) or use circumlocution (e.g., it's the bit you need to make sure the juice doesn't spill over etc.). All of these things are difficult in a foreign language.

- informal

- learners of a language often sound overly formal and precise because they are trying hard to be accurate and orderly. Native speakers care less about these things because they have more resources and can be more innovative.

- rhetorical

- spoken language is often, for example, laden with modality (should, must, could, ought to, probably, certainly, if you get a mo' etc.) and such forms are difficult to deploy accurately in a foreign language.

- inter-personal

- picking up on the attitude of the person we are talking to and responding appropriately is something that native speakers do unconsciously, taking clues from body language, intonation, lexical choice and much else. That's hard to learn to do in a second language.

Add all these factors together and we get three major processing pressures:

- Time

- Preparation level

- Topic familiarity

and three main social pressures:

- Size of the audience

- Familiarity with the audience

- Roles of the people involved

|

Easing the pressure |

To help our learners, we need first of all to look at the ways that native speakers deal with all these issues. Here's how they do it:

| Processing pressures | Coping strategies |

| Time | Native speakers deal with

time pressure in a number of ways:

|

| Preparation level | Native speakers don't plan.

They are happy to string ideas together as they occur using

simple connectors like ... and ... and ... or ...

and then ... and then ... or ...so... so ... etc.

That's called parataxis, stringing independent clauses together

with simple connectors. Speakers will more rarely use what's called hypotaxis, making one clause dependent on another such as in The car which is parked over the road The man whom I saw in the café She came only because you asked her to etc., all of which are more frequent in written language when time is not a pressure. Listeners don't expect to hear well-formed, planned utterances in most cases. In this case, too, native speakers are happy to resort to colloquial and imprecise language and to simplification. One of the hallmarks of spoken language is that it is simpler than written language, both grammatically and lexically. False starts such as He was with his friends ... Actually not all of them were his friends but anyway etc. are common. |

| Topic familiarity | Native speakers are least

at ease and least competent when talking about unfamiliar

subjects so they tend to avoid them, keep quiet or speak more

slowly with lots of fillers such as Well, let me think I'm not sure but ... etc. Fillers like these, which are, again, prefabricated and formulaic, allow the speaker to think while not giving up a turn. Silence often betokens the end of someone's turn in a conversation and fillers are a way to avoid silence and retain the turn. |

| Social pressures | Coping strategies |

| Audience size | If called on to speak to

large numbers of people (and 'large' is a relative term), native

speakers take opportunities to prepare what they will say

carefully or use notes. Many native speakers are still

intimidated by speaking to large numbers of people and some will

avoid it if they can. By contrast, in classrooms foreign language learners are often called on to say something in front of all the other members of the group and that is something they may not be familiar with doing even in their first language. |

| Familiarity with the audience | When speaking to people we

don't know, native speakers often use more formal or neutral

language, avoiding slang and colloquialism. They also say

less. In a foreign language one may not have adequate resources to be able to express things more formally or to tune our output to the setting so this is an added pressure of knowing that what you are saying is probably inappropriate but being unable to refine it with the care you know it needs. |

| Roles | When roles are equal or the

speaker is in a superior role, speakers feel free to use all the

tactics above to make speaking easier. When speaking to

superiors, preparation is needed and a more formal tone adopted. Learners of a language do not usually have the linguistic resources to alter what they say to suit the audience. |

|

Helping the listener |

Apart from helping themselves process and produce language under pressure, native speakers also help the listener in a number of ways in the effort to be clear. These include:

- substituting one word for

another, for example:

That image ... er ... photograph over there is ... - repetition of nouns and verbs,

for example:

The picture of ... the picture of the man and the woman walking ... with the woman walking in the background ... - reformulation by rephrasing,

for example:

- It's set in a large building ... like a warehouse or a hanger or something ... and there are ...

- self-correction and

backtracking to repeat or correct things or say them more clearly,

for example:

I started to get on the train ... no, I was still on the platform, in fact, and I saw him ...

These strategies, adopted to help the listener follow the discourse are unconsciously applied in people's first languages but in second and additional languages, they need to be learned.

|

Facilitation and compensation |

These are two rather blurry terms for the ways speakers have of making things easier for themselves or easier for the listener (or both). Some of them have been mentioned above but here's a summary for your reference.

- Facilitation

- means making things easy (or easier, anyway) and speakers

can do this in four main ways:

- Simplifying the structure of sentences. We saw above

that native speakers routinely use hypotaxis when speaking in

longer turns, stringing clauses together with simple linking

words like and, but, then etc. This is

not usually acceptable in anything but the most informal writing

but is very frequent in speech so, for example, instead of:

In order to avoid the heavy holiday traffic, John took the train and, consequently, arrived at work in good time so he was able to attend the meetings.

we might have:

John took the train because the traffic was heavy and he arrived at work in good time and was able to attend the meetings. - By leaving things out (ellipsis, in the trade).

Anything which can easily be understood by the hearer is often

simply omitted so, in answer to, for example:

I don't want to come to the party with you

the answer will often be:

Why not?

rather than

Can you explain why you don't want to come to the party with me?

In written language, it is more difficult for the writer to know what the reader already knows (because the reader may be reading the text in a different place at a different time) so care is taken to include precise information. Speakers don't need to do that. - Using prefabricated, formulaic expressions. So, for

example, instead of saying something like:

I find it difficult to believe that's the case

we might prefer a cliché such as:

I'll take that with a pinch of salt

because idioms and other prefabricated chunks of language take the speaker less time and effort to process and construct. Such chunks are stored as single units and don't need to be built up from scratch. - Using time-buying fillers and hesitation devices. In

order to avoid interruption and keep a turn going, speakers

often rely on these sorts of utterances:

Er, let me think, well, as far as I can see, erm ...

So, now, as I see it ...

Erm, well, I mean, you know, like, sort of ...

Clearly, such devices are rare and unnecessary in written language where the writer can take as long as needed to construct a response.

- Simplifying the structure of sentences. We saw above

that native speakers routinely use hypotaxis when speaking in

longer turns, stringing clauses together with simple linking

words like and, but, then etc. This is

not usually acceptable in anything but the most informal writing

but is very frequent in speech so, for example, instead of:

- Compensation

- means making up for a lack of something (in this case,

language and fluency) and speakers can do this in main

ways:

- Circumlocution. Even native speakers do not know the

words for everything that exists or happens around them.

Learners of the language are even less likely to have a wide

enough vocabulary to cope in all situations so the ability to

use circumlocution and define the term is a key skill. For

example:

It's the thing that ...

It's when you ...

It's used for ...

etc. are all ways of talking around an item for which you do not know the word. - Wide-range words. The word car, for

example, covers a lot of ground and includes sports car,

saloon car, 4x4 vehicle, SUV, people carrier and more.

It's a very useful word when you don't know how to talk

about a specific type. Other examples are:

a garden tool for ... (instead of hoe, rake, spade, fork, trimmer etc.)

building (instead of cottage, bungalow, office block, mansion etc.)

machine that ... (instead of shredder, lathe, drill, press etc.)

animal (instead of cat, kitten, lion, rhinoceros etc.)

The wide-range word is often a hypernym or superordinate (see the in-service guide to lexical relationships for more (new tab)). - Mime and gesture.

Failing all else, many learners will deploy mime for simple concepts and that can be quite effective even if it is uncertain, slightly embarrassing and often misinterpretable.

Gesture includes pointing at things or making simple but meaningful hand and body movements to express what you are referring to and what you want to say. - Asking for help. Learners can be trained in simple and

effective ways of asking their interlocutor(s) for help using

expressions such as:

What's the word for the thing / animal / machine / etc. that ...

What's it called when a horse runs really fast?

What's the name of the place where you keep ...

etc. These sorts of requests do not, incidentally, means that the speaker is giving up a turn.

- Circumlocution. Even native speakers do not know the

words for everything that exists or happens around them.

Learners of the language are even less likely to have a wide

enough vocabulary to cope in all situations so the ability to

use circumlocution and define the term is a key skill. For

example:

|

Turn taking |

In addition to all this, speakers have a repertoire of ways to keep conversation moving along by signalling opportunities to take turns in speaking. There are five things that speakers have to know about turn taking (from Bygate 1987):

- Knowing how to show that you want to speak. This can involve noises or phrases (Hmm. Yes, but ...), gestures, intakes of breath and a number of other tactics.

- Recognising when to take a turn. Speakers often signal appropriate moments by assuming eye contact, falling voice volume or stopping and looking.

- How to hold one's turn by such techniques as starting with Well there are two things here ... or keeping the intonation up to show you haven't finished.

- Recognising other people's desire to take a turn (in other words, noticing the signals in 1., above).

- Knowing how to let them have a turn by gesture, look or phrase such as the use of question tags or straightforward questions.

There is a separate guide to turn-taking skills – covering what they are and how to teach them – on this site, linked in the list at the end of related guides.

|

The structure of conversation: IRF sequences |

No analysis of speaking would be complete without some discussion of how conversation is structured. A simple but effective way of analysing this structure is to consider 3 main phases. The following is based on Tsui (1994):

- Initiation.

There are four ways to start a conversation:- Elicit (ask if). E.g., Have you eaten?

- Request (ask to). E.g., Can I ask you something?

- Direct (tell to). E.g., Pay attention to this; it's important.

- Inform (tell that). E.g., I noticed you didn't come to the meeting.

- Response

There are three types of response to an initiation. For example to the Initiation, Can you do me a favour? we can have:- Positive (preferred): Yes, sure, what can I do?

- Negative (dispreferred): Sorry, I need to go now.

- Temporising (dispreferred): Maybe. Will it take long?

- Follow up

There are also three sorts. Following from the three responses above, we can have:- Endorsement (positive). Great.

- Concession (negative outcome). Oh, I see.

- Acknowledgement (negative outcome). It's OK, I'll get John to help.

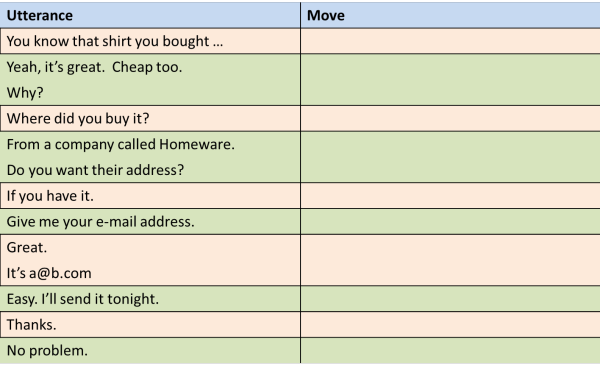

So we can have an analysis like this in the three 'moves' in a conversation:

| Utterance | Move |

| Where did you buy your shirt? | Initiate: elicit |

| From a company called Homeware. | Respond: positive |

| Thank you. I see. | Follow-up: positive outcome |

This is nice and simple but there's a problem. Real people just don't talk like this. Here's a more natural-sounding conversation. Can you do the analysis into I R F moves? Click on the table when you have.

Whether you got all that right or not doesn't matter too much now. What does matter is that you see why this conversation is more natural than the last one. Click here when you see it.

Right. Speakers conduct

two moves in their

turns. The second speaker responds with

Yeah, it's great.

Cheap too

but in the same turn starts a new

initiation with

Why?

This is the way many conversations

go.

One of the reasons that learners often say that native

speakers won't speak to them or that they find it hard to keep

conversations going is that they have failed to see that conversation

requires maintenance with new initiations in most response turns.

|

Speech acts and illocutionary force |

Say you come across a stone with some strange markings engraved in

it. You take it to an expert and she decides to spend time

investigating the marks and attempting to decipher their meaning.

What are you both assuming?

Click

![]() when you have an answer.

when you have an answer.

You are assuming, naturally, that the marks on the stone were

deliberately put there by a creature much like you who had an

intention to make meaning in the marks he or she inscribed on the

stone.

If both your and the expert's view was that the marks had been made

by some kind of natural process, scratching with ice in a glacier or

erosion by water in a river bed, say, neither of you would have

bothered to give the stone a second thought.

This is precisely the case when someone speaks. The assumption

is that someone has spoken for a reason and that reason is to do

with an attempt at communication. This is what a speech act

is: a deliberate utterance intended to communicate a meaning,

speech as action in other words.

The teaching of speaking has to start with the communicative

intentions of the speaker or it is a pointless exercise in the

manipulation of language. That purpose may be, for example, to

state a fact, assert a truth, describe something, warn against

something, comment on something, command someone, order someone or

something, criticize, apologize, welcome, promise and many more.

Given a moment, you can probably add significantly to that list.

The problem faced by learners of English (or any other second

language) is selecting the linguistic realisation of what it is that

they want to do. It is not a trivial problem because what may

look like one type of utterance such as a command, may, in fact,

have a wholly different function, that of offering or warning, for

example.

Speech acts are culturally defined and the illocutionary force of

what is said refers to the speaker's intended meaning, not the

language which is used.

Some examples may help.

| Utterance | Face value | Possible intended meaning |

| Is lunch ready? | An enquiry about a fact concerning readiness | An order: Bring me my lunch! |

| I'm cold | A statement of fact about how one feels | A request: Please shut the window |

| Come in | An order to enter | Welcome! |

| I'm sorry | An apology | A criticism: Be careful what you say to me! |

| That step is icy | A statement about the condition of something | A warning: Be careful! |

The third column is headed Possible intended meaning because what an utterance will mean depends on the relationship between the speakers, the situation, the environment around them and their own thoughts and intentions.

In the classroom, this sort of analysis has value because it is common, indeed usual, to proceed from a model of speaking to getting the learners to develop and improve their own oral production. If it is not clear what the speakers' intentions are in the model which is presented (the illocutionary force of the speech acts), confusion and error will result.

Making the speakers' intentions clear is also not a trivial matter and it may involve quite a lot of additional information about the setting, the power relationships between speakers and so on. Not giving the information is not, however, a viable option.

All the above is teachable but before we see how, take a test to make sure you have understood.

| Related guides | |

| teaching language skills | this is an overview of what you and your learners need to know when developing or practising skills |

| teaching speaking | for the essentials-only guide to how we may develop our learners' speaking abilities |

| communicative strategies | for the in-service guide to some of the ways we manage speaking and interactions |

| assessing speaking | for the in-service guide to assessing speaking skills abilities |

| spoken discourse | for a more technical guide to spoken language in the in-service section |

| semantics | the in-service guide to meaning which includes more consideration of illocutionary force |

| turn taking | for the guide to an essential speaking skill |

| backchannelling | for a guide to a key speaking skill often related to turn taking |

| speaking for EAP | for the guide to the kinds of speaking skills which are required in academic contexts |

| teaching vocabulary | for the in-service guide to teaching meaning |

| context | for a guide to the essentials of context and co-text |

| skills index | for the index to the overviews of the four main language skills |

References:

Bygate, M, 1987, Speaking, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Tsui, ABM, 1994, English

Conversation, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Other references you may find helpful:

Brown, G & Yule, G, 1983, Teaching the Spoken Language,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bilbrough, N, 2007, Dialogue Activities: Exploring Spoken

Interaction in the Language Class, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

Hughes, R, 2002, Teaching and Researching Speaking, Harlow:

Longman

Luoma,

S, 2004, Assessing Speaking, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

Maley, A & Duff, A, 1982, Drama Techniques in Language Learning,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Porter Ladousse, G, 1987, Role Play, Oxford: Oxford University

Press

Rogerson, P & Gilbert, JS, 1990, Speaking clearly: pronunciation

and listening comprehension for learners of English Student's Book,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press