Strand 7: Recording classroom talk

Sooner or later, in most development programmes, there will come a time when you will want to record what actually happens and what is said in a classroom. The natural follow-on is that you will need to make some kind of transcript of parts of the recording for later study and consideration.

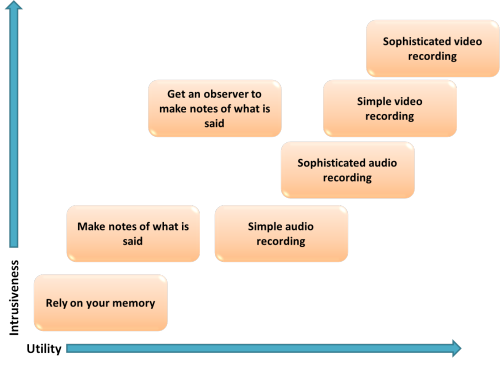

The first problem we encounter is what Labov called 'the observer's paradox' – that the act of observing behaviour changes the behaviour we observe. There is no simple way around this (and some would suggest that we shouldn't be looking for one) but the usual consideration is that the more intrusive, novel and obvious our data-gathering tools, the more the behaviour we want to record will be changed. With that in mind ...

|

Ways to record what happens and what is said |

There are three approaches to recording what happens in a classroom: making notes, making an audio recording and making a video recording. They all have their benefits and drawbacks.

- Making notes

- relying on your memory is the least intrusive way of

recording what happened and what people said during a lesson

because the notes can be made privately after the lesson is

finished and nobody need know that any record at all was kept.

The obvious drawback is that you need a very good memory!

The data you get from this approach may well be affected by all sorts of factors such as your ability to remember what was said and done, our natural tendency to fill in gaps in our knowledge with our imaginations and so on. - writing your own notes as you go along can also be quite unobtrusive if done carefully but the downside is that you are usually quite busy in the classroom and often especially so at the times when you want to record what is being said to you and by you.

- getting someone else to write notes as you go along is clearly a solution to the time problem but it raises the level of intrusiveness because many will find a silent note-taker in a classroom quite threatening and disturbing. In most cases, taking this route means that the observer-recorder is trying to write down two sorts of information simultaneously: what is being said and what people are doing. That's a skill few have.

- relying on your memory is the least intrusive way of

recording what happened and what people said during a lesson

because the notes can be made privately after the lesson is

finished and nobody need know that any record at all was kept.

The obvious drawback is that you need a very good memory!

- Audio recording

- simple audio recordings can be made with many small devices but background noise and people's habit of talking simultaneously will make the actual words people say very hard to distinguish. The human ear and brain are good at filtering out background noise and other people's conversations (the so-called 'cocktail party effect') but audio recorders will pick up all sound indiscriminately.

- more sophisticated audio-recording equipment, involving, e.g., multiple personal microphones, can overcome the drawbacks but at the expense of being much more intrusive and making the observer's paradox more obvious. Really sophisticated equipment can even make it difficult for people to move around and pin the learners and you to a single chair.

- Video recording

- simple video devices, such as a mobile phone, are good only for very simple situations. Getting the big picture of what happened and was said in the whole room will probably be simply impossible with such a device. Even a single camera operated by someone who can move around the room will often be too selective and intrusive so the data will be compromised.

- sophisticated video recording requires multiple cameras and microphones and can be very intrusive indeed. It provides the best results, of course, but often at the cost of compromised data and learners being reluctant to speak at all.

The relationship between the quality of the data you gather, its utility, and the intrusiveness of the methodology can be summarised like this:

|

Making a transcript |

Transcribing even a short piece of classroom interaction is very

time consuming. Roughly, one minute of interaction requires 15

minutes of work to transcribe it accurately. Ten minutes,

then, will take two-and-a-half hours to transcribe.

Unless you are a quite unusually time-rich teacher, you need to be

selective.

|

Focus |

Decide what it is that you want to investigate from the recording and narrow down to the sections of the recording that will help you. For example

- if you want to focus on the teacher's (your?) instructional language, only transcribe the instructions and then make notes of the actions of the learners. Did they understand? Did they do what was required? Did they need to ask for clarification?

- if the focus is on who said what in a student group, transcribe that exactly and then you can focus on who contributed the most / most usefully.

and so on.

|

Transcription conventions |

There's no right way to set out a transcription, especially if

it's only for your own use. However, if you want to share the

transcription with others, it's as well to follow some basic rules

so that it is accessible.

Essentially, there are two ways to set about the task:

|

1. Dialogic transcription |

This looks a little like how dialogue is set out in a play or film script but, because real speaking tends to be quite messy and disorganised, there are some simple conventions to use. Here's an example:

| The class is arranged in a horseshoe shape behind desks. There are 7 teenage students. The teacher is at the front of the class between a table and the whiteboard. | |||

| Turn | Speaker | Utterance | Notes |

| 1 | T | OK. Right. Now listen, please. | Claps hands to get attention |

| What do you think this is? | Sets an unusual, old leather briefcase on the table | ||

| 2 | S1 | {a bag} | |

| 3 | S3 | {a handbag} | |

| 4 | S4 | It's a case | |

| 5 | S2 | ( .... ) | |

| 6 | T | OK. Good (.) It's called a briefcase | Writes on whiteboard |

| Together ... briefcase | Gestures for everyone to speak | ||

| 7 | Ss | briefcase | |

| 8 | T | This briefcase is very important to me. Can you guess why? | |

| 9 | S2 | Is old | |

| 10 | T | Yes, it is, but that's not the only reason | |

| 11 | S5 | It's expensive <laughs> | |

| 12 | T | No, actually, it was a present | |

| 13 | S4 | It's special ( ... ) from someone ... from someone special | |

| 14 | T | Good. Yes exactly. My mother bought it in Morocco and gave it to me when I started my first teaching job. It goes everywhere with me now. I love it and it gives me good memories. | |

| Key | |||

| S1 etc | Individual learners | ||

| Ss | All learners | ||

| T | Teacher | ||

| (.) | Pause | ||

| { } | Overlapping speech | ||

| < > | Sound | ||

| ( ... ) | Unclear speech | ||

This kind of layout is useful for whole-class interactions and for focusing on what the teacher says and does.

|

2. Group-talk transcription |

This is a useful way to focus on what individuals say when learners are working in groups. It is, for obvious reasons, sometimes call a column transcription. Here's an example from a lesson used to follow up the one above:

| The group is arranged three on each side of a large table. | |||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | Notes | |

| 1 | I bring this book | Shows old book | |||||

| 2 | Why that? | ||||||

| 3 | My father give it to me when I began university. I like very much | ||||||

| 4 | I bring this <all laugh> | Shows old teddy bear | |||||

| 5 | {Why} | {Why that} | |||||

| 6 | <laughs> It's my first teddy bear. I sleep with him now <all laugh> | ||||||

| 7 | And you? | Looks at S3 | |||||

| 8 | Nothing. I forget | ||||||

| 9 | I bring my old ... erm ... what this called ... recorder | consults dictionary (2 minutes silence) | |||||

| 10 | Why that | ||||||

| 11 | I learn first this | ||||||

| 12 | You play | ||||||

| 13 | No, now I play clarinet | ||||||

One advantage of this form of transcription is that it is easy to

see at a glance that S1, S2 and S4 are the most forthcoming with the

other three students saying very little (up to now).

The key will be the same for both transcriptions but you may have to

add, e.g., [?] for something doubtful or [ ... ] to show that you

have left something out.

|

Using transcriptions |

It should be clear by now that the great strength of using

transcription in this kind of detail is that it allows you to see

patterns and events which would normally be 'camouflaged' by all the

other things going on in the classroom.

In the two examples above, the fact that 2 students, at least, were

not involved at all in the teacher's introduction and elicitation

and that none of the students in the group discussion and exchange

took the obvious opportunity to use the present perfect (I have

brought ...) or were able to form a question with why

correctly might easily have been missed by any observer, especially

one who was also involved in the exchanges.

It has been noted that transcribing a lesson is very time

consuming but you don't have to transcribe everything at once.

You can return to the recording and focus on a different stage of a

lesson and transcribe just that bit for further study at any time,

of course.