Business English: an overview

Business English or, sometimes, English for Business is a wide

area and we need to define our terms by the settings in which the

language will be learned and used, the kinds of teaching we are

talking about and the kinds of English we are teaching.

In general terms, English for Business lies firmly in the field of

EOP (English for Occupational Purposes) but that term covers a wider

area as it includes, for example, English for Science, English for

Aviation and a host of other registers.

Here's a working definition of Business English:

Business English is the sort of English used in the registers of, at least:

|

|

|

For our purposes, we'll define business as any sort of commercial, managerial or administrational activity in any of these fields.

It should also be remembered that people who work in fields which

are not, on the face of things, to do with business and commerce

nevertheless use language and functions which are business-like.

For example, more and more, school administrators, health workers,

teachers, charity workers and many others are frequently involved in

dealing with suppliers, partner organisations, large industrial

concerns and more.

We should also bear in mind that in our private, non-work activities

all of us commonly deal with commercial transactions and need the

language to do this. Most often, naturally, people deal with

such things in their first language(s) but, in an increasingly

interconnected world, it is not at all uncommon for people to find

themselves dealing with companies based in other countries and, as

is the way of things, the language default is English, simply

because it is the dominant lingua franca in business

settings.

|

BELF |

BELF stands for Business English (as a) Lingua Franca.

It is not guaranteed that when two people who do not share

a working knowledge

of each other's languages meet to do business that they will speak

and write in English but that is most certainly the way to bet.

There are reasons for this:

- Popularity

Here are some salient facts:- One in four people on the planet uses English either as a first or a second language and the number is growing as more and more people get access to the internet and other resources.

- Over 60% of all websites are in English. That's around 720,000,000 websites out of the estimated 1.2 billion of them.

- Among journals recognised by Journal Citation Reports, 96% are in English.

- 75% of the world's mail is written in English.

- 80% of the world's electronically stored data is in English.

- English is the main language of books, newspapers, airports and air-traffic control, international business and academic conferences, science, technology, diplomacy, sport, international competitions, pop music and advertising.

- Efficiency

It is also the case that international companies are turning to using English as their internal means of communication because they recognise that the inconvenience and ambiguity which can be caused by people using a range of languages within the same enterprise is a serious impediment to efficient management and productivity.

It is difficult to get exact or reliable figures but writing in The Harvard Business Review (2012), Neeley cites at least Airbus, Daimler-Chrysler, Fast Retailing, Nokia, Renault, Samsung, SAP, Technicolor, and Microsoft in Beijing as corporations using only English as their internal language. Neeley goes on to note that when Germany’s Hoechst and France’s Rhône-Poulenc merged to create Aventis, the fifth largest worldwide pharmaceutical company, the new firm chose English as its operating language.

Honda in Japan also uses English as its corporate language and its spokesperson, Yuka Abe, is quoted as saying: By declaring to our stakeholders that Honda, as a global company, will make English our official language, we are aiming to raise our presence and transparency as a global company.

Volkswagen, a German company with a German name, has also adopted English as its internal working language (despite some heartfelt protests from linguists and others in Germany). - International Cooperation

Non-commercial, governmental and international bodies also use English as their working language even when they are not based in or conduct most of their activities in English-speaking cultures.

These include institutions as widely varied as The International Monetary Fund, The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Companies, The Union of South American Nations, The Council of Europe, World Rugby and The World Trade Organisation.

Thus the market for courses in Business English is huge and set to grow. The only question which remains, of course, is to say what it is.

|

Blurred edges: issue #1 |

Business English is not an easily defined concept because there are significant overlaps with other areas of English for Specific Purposes (which are themselves not particularly specific or specifiable) and because it all depends on what sort of business one is considering. For example:

- Manufacturing businesses

- In this field, there is often considerable overlap with

English for Science and Technology and that is especially true

when high-tech industries such as the automotive, chemical and

pharmaceutical industries are concerned.

Depending on their role in the organisation, people will need more or less scientific and technical language to communicate with colleagues, managers, subordinates, suppliers and customers.

Some roles will focus almost solely on the technical aspects of the corporation and some will have little to do with them, being more concerned with, e.g., finance or customers relations. - Service industries

- Far fewer employees of service industries will need to

acquire the ability to use English for Science and Technology

but they are much more likely to be concerned with systems,

services, employment policies, customer relations and, possibly,

finance and insurance issues.

There will, therefore, be considerable overlap with both English for Media and Customer Relations, English for Human Resource Management and English for Banking and Finance. - Financial houses

- Employees in financial environments (stock broking, banking,

insurance and so on) will obviously need English for those

sectors but may also, depending on their roles and

responsibilities, be concerned to acquire language to help them

communicate well with customers, investors and suppliers and to

manage internal systems.

English for Science and Technology insofar as it concerns IT systems and secure communications and data storage will also figure highly on some people's needs lists.

Roughly speaking, the picture is:

|

Variety: issue #2 |

This presents us with our first problem: the sheer variety of settings and purposes. We can, however, divide the area up a little more carefully and start to make some kind of sense.

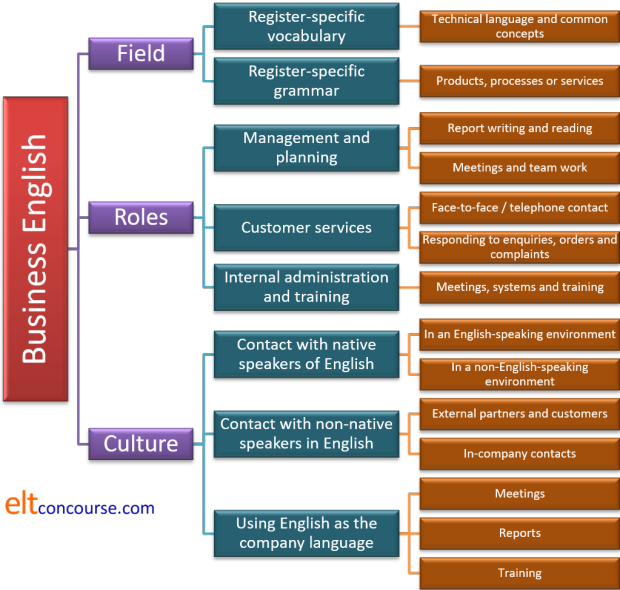

- Field

- The kinds of language which will be needed by someone

working in international banking and finance will possibly be

similar to the needs of someone working in insurance or other

arms of the finance sector. They will however, differ

quite markedly from the needs of someone employed in the

automobile industries and someone working in retailing will have

different needs again.

This will affect mostly the vocabulary which people need to command but also the skills they need to master in terms of talking about a product, a service or a process and that, in its turn, affects the kind of structures they will need to control. - Roles

- Someone whose position in a company requires them to have

face-to-face and email contact with clients will have very

different needs from someone in the same company whose role

concerns management and planning. Someone in the same

company whose day-to-day concerns involve training colleagues in

IT systems and data management will have different needs again.

The different roles people have will radically affect the skills and language they need to master. - Culture

- Someone who is a non-native speaker of English who needs to

live and work in an English-speaking culture will have very

different needs from someone who rarely makes contact with

native speakers of English (or their cultures). Someone

who works for one of the many multinational businesses, wherever

they are based, which have embraced a company-wide internal

English-speaking culture will have different needs again.

This will affect the levels of language they need to deploy and the communicative skills they need to master.

Here's a summary so you can see where in the chart you may find your learners and act accordingly.

The situation is further complicated, of course, by the need to

locate each person in each area.

For example, a middle manager working in a multi-national company

which has chosen English as its working language may be involved in

manufacturing, administration or training and may have to be in

contact with other non-native English-speaking colleagues to plan

and implement systems or with native English-speaking

representatives of customers and suppliers.

Someone whose role is largely an internal support role may never

have to deal directly with customers and suppliers in any language

but may need to train colleagues in English and present ideas and

proposals to meetings of managers and other staff.

In an ideal world, of course, each set of Business English learners would all be situated in the same places on this chart, working in the same fields, having similar roles and cultural settings, and it will be possible to plan and deliver a course which meets their specific needs. That can occur but is rarely the norm in teaching Business English.

|

Types of training and setting: issue #3 |

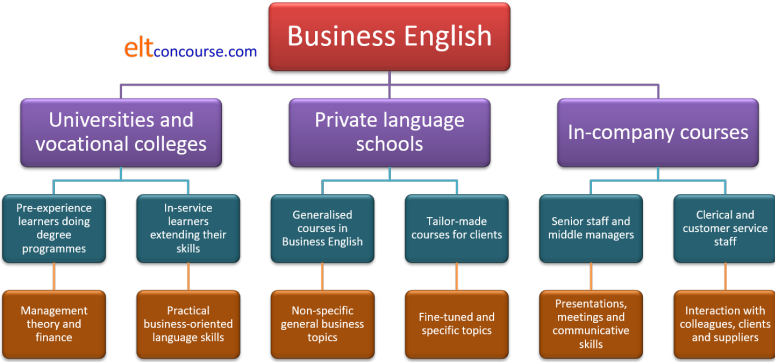

Business English teaching, like any other form of English-language teaching, occurs in a range of settings and they all have peculiar opportunities and challenges.

- Universities and vocational colleges

- In most cases, people studying in these settings are

younger, pre-experience learners who are under no pressure to

apply their skills immediately in the 'real' world. Such

courses come in four main types although there are almost

infinite variations across the board.

- Undergraduate generalised courses: focusing on large areas of commerce and business such as management, administration, finance and accounting. Such courses are rarely narrowly industry specific and the participants need more general language to talk, write and read about business.

- Industry-specific undergraduate courses: focused on a particular industry and often sponsored or run in partnership with major firms in the area. Participants on these courses will be much more narrowly focused on the demands of their field.

- Vocational colleges: courses leading to qualifications below degree level which may be extremely narrowly focused on one particular area or may be much more generalised. Participants on the first type of course may be sponsored by their employers and studying part-time to enhance their skills and on the second type of course, they may be less focused and concerned only to get a portable qualification to use as an entrée to the workplace.

- Post-graduate courses: often leading to a Masters in Business Administration. Participants my be following on from a first degree and not be too predictably focused on a specific industry (although they may well have one in mind) or they may be mature people taking time out to gain qualifications which will allow them better career prospects and greater mobility in the workplace. In neither case will they expect specific industry-focused materials and teaching as the focus is on theory rather than day-to-day practice.

- Private English-language teaching institutions

- While there is much variation, the private sector is usually

concerned with two types of courses:

- Generalised, short courses in Business English.

Disparagingly, such courses have been described as expensive

General English courses with a carpet on the floor.

They may be taken full-time in an English speaking nation or part-time in other settings. In neither case is it possible to focus on specific industries or employment roles because the course cannot be designed to cater for people in that way. - Tailor-made courses for companies. Some private institutions in all settings are able to set up a relationship with businesses to train their employees in Business English skills. Often these courses are very specific indeed, focusing on people in particular roles in a single company. At other times, although the company background may be the same, the group may be made up of people in a range of roles and the design of a course becomes quite problematic.

- Generalised, short courses in Business English.

Disparagingly, such courses have been described as expensive

General English courses with a carpet on the floor.

- In-company courses

- Some large enterprises have the resources to establish their

own in-company language training programmes. Usually,

these function as a department of a larger training facility.

Commonly, such programmes are aimed at middle or senior

management and will be both role and field specific.

People in this category may be focused on the language and

skills they need to participate in meetings or give

presentations.

Sometimes, however, there will be an effort to train all workers in English language skills because the company has a policy of using English internally wherever the employees are working in the world. In the latter case, more generalised communicative training is required to help people to function in their roles, especially when it comes to contacts with suppliers and customers.

Here's a short summary:

|

What learners want |

Teachers of English who have been trained conventionally often take it as a given that it is communicative competence rather than grammatical or phonological accuracy that should be the goal of their teaching. In a Business English environment, that may not always be wise.

While evidence from international studies is sparse, those which

have been carried out seem to suggest that it is grammatical,

lexical and, perhaps above all, phonological accuracy that many

learners of Business English prize, often above communicative

effectiveness.

Business English is often used in situations which are, more or

less, formal and stiff and it is precisely in such settings that

accurate use of grammar and lexis and good pronunciation skills are

needed most. There are good reasons why formal accuracy is

important to Business English learners:

- Formal accuracy of grammar inspires confidence in the listener especially if the listener is a non-native speaker of English with high-level accuracy skills. Native speakers, too, are impressed by people who control their language better than they control the speaker's language (if they control it at all).

- Good use of lexis allows for clarity and precision in what one says and both are valued highly in formal business situations where it may be legally and commercially very important to get things right and use the correct terms.

- Good pronunciation allows people to speak without imposing a

strain on the listener and allows the listener to focus better

on the content of what is being said rather than the way it is

being said.

This is especially the case where interactions are with native English speakers. Native speakers will forgive many grammatical and lexical inaccuracies and may be sympathetic readers and listeners willing mentally to reconstruct to get the message clear but they are rarely very sympathetic to intonational and pronunciation errors.

Swan, 2002, referring to grammatical accuracy put it this way:

In some social contexts, serious deviance from native-speaker norms can hinder integration and excite prejudice – a person who speaks ‘badly’ may not be taken seriously, or may be considered uneducated or stupid. Students may, therefore, want or need a higher level of grammatical correctness than is required for mere comprehensibility.

So, while communication is valued, many Business English users

see formal accuracy as the way to get to communicative competence.

They know that they do not want to excite prejudice or not be taken

seriously and they certainly do not want to be seen as uneducated or

uninformed.

A study (Trinder and Herles, 2013) of a particular set of Business

English students in Austria concluded that learners often value

accuracy more highly than their teachers. They report:

... though learner and teacher beliefs tend to be aligned in most areas, students’ judgements of effective teaching and learning practices are highly dependent on personal motivations and specific language use purposes, and this difference manifests itself most clearly in teachers’ and learners’ divergent views on the value of grammatical accuracy and corrective feedback.

There seems no obvious reason to assume that these Austrian

learners were unusual in valuing formal accuracy.

They may be wrong, but ignoring their wishes is not a good way to

begin or a good way to maintain commitment and motivation.

|

Planning and teaching |

If you have kept up so far, you will have been alerted to the

fact that planning for a Business English programme will not be a

simple matter.

So, what do we have to bear in mind before we even meet our

students?

- Field, roles and culture

If we are fortunate, the individuals in the group will share one or more of these characteristics.

However, even when the participants are operating in the same general field or register, they may have very different roles and cultural issues to contend with so, while they may share a lexical need for their industry-specific terms and expressions, they may vary widely in their skills and communicative needs so any programme needs to be adjusted and designed to take this into account. - Teaching and learning setting

Even within a single institutional type, the format of courses will be variable depending on the way a programme has been set up, marketed or proposed. Who the programme is intended for, how the groups are constituted and what the aims of the individuals are will have a substantial influence on how a course is designed and delivered.

This all leads us to consider how best to establish:

- the topics that the learners will need to feel confident talking, writing and reading about

- the roles in which learners will use the language and the skills they will need

- the cultural factors which may be in play

and to do that, we need to do some research: a needs analysis.

|

Needs analysis |

All the considerations so far have been leading up to this. Before we can begin to design a needs analysis and from it a programme of teaching, we need to be aware of the parameters in which we are working: the field, the roles, the culture and the setting.

Elsewhere on the site, there is a guide, linked below, to how to

approach a needs analysis so here we will be focused on what we need

to know about the learners and their use of English in a business

setting and only briefly with how we are going to gather the data we

need.

For advice and examples concerning how to pose questions, see the

guide.

Even before we conduct a needs analysis, there are some questions to which we already have the answers. We will know, for example whether the learners are:

- pre-work or in-work

- operating within a company-wide English medium policy or only using English for external contacts

- working and living in an English or non-English speaking setting culturally

We may also be able to answer a number of questions about the course because we already know:

- where the course will be conducted: in a university, a college, a private language institution or in-company

- how long and how intensive the course will be

- what materials and equipment are at our disposal

What we may not know is what we need to find out and that will include:

- What roles the participants play in their business setting

- Who they have to communicate with

- How they communicate, i.e., which media they habitually use

- What functions they need to master

- What forms of interaction they need to participate in

- What they prioritise and their attitudes to what they need to learn

We can take each one separately and see how we might set about finding some answers.

We can gather data in one of two ways (and sometimes we can use both.

- On paper: questionnaires, written prose responses from learners and so on.

- Face-to-face: interviews, focus groups, discussions etc.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both forms of data gathering:

| In writing | Face-to-face | ||

| For | Against | For | Against |

| can be cheaply administered at a distance | is impersonal and often not monitored | is personal and can be carefully monitored | may be expensive in terms of time and travel |

| is fixed and reliable: everyone answers the same questions | is inflexible: later questions can't be premised on earlier responses | is flexible and can be altered to suit responses received | becomes unreliable with too much alteration |

| can be carefully constructed and designed | errors in the questions cannot be eradicated | can be altered easily if a question is flawed | relies on a subjective judgement of what is said |

| results can be carefully, statistically analysed | little data concerning strength of respondents' feelings | judgement about strength of feelings can be made | it is difficult reliably to collate and analyse results |

|

roles |

We may, of course, already have the information that the participants have a certain role within their organisations but job descriptions rarely tell us what people do; they merely describe how they are seen by the company. Job descriptions will never tell us what people do in English of course. To get a bit more data we could set a questionnaire item like this:

| In a typical week at work do you use English for ... | |||||

| Never | Almost never | Sometimes | Often | Very often | |

| Talking | |||||

| on the telephone | |||||

| face-to-face | |||||

| video conferencing | |||||

| at meetings | |||||

| as the chair of a meeting | |||||

| to present at meetings | |||||

| to train colleagues | |||||

| informally with colleagues | |||||

| to negotiate | |||||

| Writing | |||||

| emails | |||||

| reports | |||||

| proposals | |||||

| letters | |||||

| contracts | |||||

| orders | |||||

| Reading | |||||

| emails | |||||

| reports | |||||

| proposals | |||||

| letters | |||||

| contracts | |||||

| orders | |||||

We may need to define our terms explicitly and explain, e.g.,

that Almost never means less than 5% of the time and so on but

people are generally poor at estimating time devoted to tasks.

It is a simple matter, incidentally, to divide the questionnaire

into the interactions which happen only internally and those which

involve customers, partners suppliers and so on. That refines

the data.

We can add to the list as we see fit.

|

people |

It is, naturally, crucial to know with whom people interact.

| In a typical week at work I need to speak to ... | |||||

| About business matters | About non-business matters | About a mix of business and social matters | By telephone | Face to face or by video conferencing | |

| people at the same level as me | |||||

| people more senior than me | |||||

| people more junior than me | |||||

| customers | |||||

| suppliers | |||||

| enquirers | |||||

| the general public | |||||

| press representatives | |||||

| In a typical week at work I need to write to ... | |||||

| Short memos | Progress reports | Emails | Formal letters | Proposals | |

| people at the same level as me | |||||

| people more senior than me | |||||

| people more junior than me | |||||

| customers | |||||

| suppliers | |||||

| enquirers | |||||

| the general public | |||||

| press representatives | |||||

It is a reasonable assumption that the activities above, which focus on productive skills will be mirrored by the need for receptive skills (listening and reading) in all the cases. We could, of course, extend the questionnaire to discover if this is true.

|

functions |

We cannot expect non-specialists to understand what we mean by language functions but we can gather useful data which we can then interpret professionally. Perhaps like this:

| When I use my English I

need to ... Please circle the three most important ones for you. |

||||

| In informal writing | In formal writing | In informal speech | In formal speech | |

| explain possibilities | ||||

| require action | ||||

| promise action | ||||

| make offers | ||||

| train others | ||||

| present ideas | ||||

| report progress | ||||

| make promises | ||||

| form relationships | ||||

| reach agreements | ||||

| deal with complaints | ||||

| apologise | ||||

| complain | ||||

| set targets | ||||

| plan | ||||

One obvious issue with matrices like this is that we need to make sure that people understand the terms on the left. For that reason, many prefer to design this in the learners first language.

|

attitudes |

It is notoriously difficult to extract clean data from

questionnaires about people's attitudes to learning and the targets

they have in mind for themselves. Often people will respond in

a way that they think they should respond or, worse, in a way that

they hope will be favourably received. If you have looked at

the general guide to needs analyses, you will be aware, too, of the

Johari window.

We can but try.

| Please rank the following FOR YOU: | ||||||

| Agree 100% | Agree 80% | Agree 60% | Agree 40% | Agree 20% | Agree 0% | |

| accurate grammar is very important | ||||||

| a wide vocabulary is very important | ||||||

| native-like pronunciation is very important | ||||||

| I must understand 100% of what I read | ||||||

| I must understand 100% of what I hear | ||||||

| communication is more important than accuracy | ||||||

| formal language is more important than informal language | ||||||

| I only need to talk about business | ||||||

| I need to write clearly in English | ||||||

| I need to write accurately in English | ||||||

| I need to speak confidently in English | ||||||

That there are 6 columns for responses is deliberate. It prevents people choosing the middle way.

All of the above are examples of just one kind of questionnaire item: matrix responses, in the trade. There are others that you can use as you will know if you have seen the general guide to needs analysis. They include ranking tasks in which people score targets and place them on a scale, alternative-response items to which people must answer simply yes or no and open and closed questions.

Only you can decide what is important and practical given the constraints placed on you.

Whatever is done must, however, produce results which are analysable or the data are useless.

| Related guides | |

| needs analysis | the place to go for the general guide to asking questions and getting clean data |

| speaking for EAP | this guide is focused on speaking in an academic context but many of the considerations are parallel in a business context |

References:

Neeley, T, 2012, Global Business Speaks English, Harvard

Business Review, available at: https://hbr.org/2012/05/global-business-speaks-english#:~:text=More%20and%20more%20multinational%20companies,across%20geographically%20diverse%20functions%20and

Swan M, 2002,, Seven bad reasons for teaching grammar - and

two good reasons for teaching some, in

Methodology in Language Teaching, (Eds.) Richards and Renandya,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

pp.148–152

Trinder, R and Herles, M, 2013, Students’ and teachers’ ideals of

effective Business English teaching, ELT Journal Volume 67/2,

Oxford: Oxford University Press