Delta Module Two: analysing language skills in the background essay

This guide concerns meeting the criteria for a Delta essay in section 3. The two criteria are:

Successful candidates can effectively demonstrate an understanding of the specific area by:

- analysing the specific area with accuracy, identifying key points

- showing awareness of a range of learning and teaching problems occurring in a range of learning contexts

This is a guide with examples, not a model.

There are a number of reasons why it is not possible to provide a

model analysis:

- When you select your topic area for a Language Skills Assignment, you will, naturally, focus on an area which your class needs to master. What that might be for you in your setting is unpredictable and any model analysis will almost certainly not be relevant in whole or in part.

- Once you have decided on your topic area, you will have to narrow down your focus by the level of learners you have in mind or by the particular subskills you are concerned with, excluding some areas of the skill so that your analysis will be in adequate depth and not a low-level, superficial survey of the whole area. How you will do that is, again, not predictable, because it will depend on the nature of your students' needs and the focus of the lesson which you have in mind.

- No analysis, here or anywhere else, can be a complete model because the word count for Delta essays is severely limited to 2500 words overall and the analysis part of your essay is probably going to around 1000 to 1500 words to allow you space to address all the other issues in the essay (definitions, teaching suggestions etc.). This means that you will, perforce, have to leave out some interesting areas of the analysis which others might decide to include. What follows is, therefore, deliberately selective and incomplete but serves to demonstrate the level of depth and precision which is needed for Delta.

- It is a matter, often, of personal preference whether you:

- address the criteria individually by doing the analysis in a dedicated section and then linking the discussion to the difficulties learners and teachers have with the topic in a following section or

- combine the analysis with the discussion of learning and teaching problems as you go along. What follows takes a separated approach for the sake of clarity and cannot, therefore, stand as any kind of model for a combined approach.

- In this guide, we will be presenting models of analysis

drawn from a range of disparate language skill and subskill areas so there

will be little sense, if any, of a coherent and cohesive

discussion. We will, whenever it seems relevant, give

examples of listening, reading, writing and speaking subskills.

You, naturally, will make every effort to keep your analysis and discussion of problems consistently relevant to your essay title and to the limitations of the scope that you set out in the introduction. - Finally, this site takes a dim view of plagiarism, as does Cambridge English and all Delta centres. There is no intention here, then, to produce an analysis which can simple be copied and pasted into an essay. Try that and you will be found out.

|

The three strands of the analysis |

For any skills background essay analysis, you need to consider three important, connected areas. You may opt to conflate the first two of these into a single section, because they are closely connected.

- Purposes:

The purposes to which the subskill(s) you have in mind may be put. For example, here you need to consider the general needs of all learners and the purposes for which they need to apply the selected subskills. - Text types:

We approach text types, whether written or spoken, in different ways depending on their nature. We do not listen to a weather forecast in the same way that we listen to a platform announcement or a lecture, for example. - Subskill analysis:

This is where your research shows. You need to look at exactly what the skill involves and how it is applied to a text.

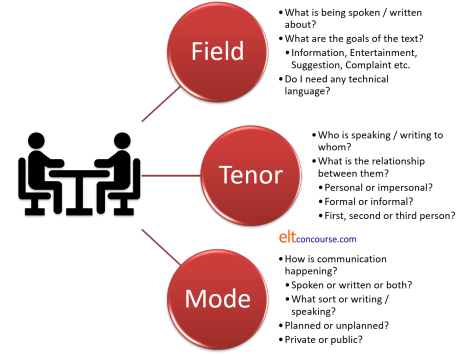

A useful place to start is with

the essential guide to teaching language skills (new tab) which sets out

what learners need to know about which skill they are using, how

they are using it, why they are using it and with whom they are

communicating. The diagram, taken from that guide looks like

this:

|

PurposesWhy do we need the skill? |

This is the central starting point for any analysis

of any skill.

Here, there are the matters of depth and detail to consider.

At Delta level, you need more of both than you may be accustomed to

considering on whatever pre-service course you have taken.

Here are two examples, one of inadequate depth but superficially

accurate analysis, the other of more depth and detail. It's

not too hard to pick which is which.

Accurate but inadequate:

People read for two basic reasons:

- to get information, for example, reading a news report

- for entertainment, for example, reading a short story

In a bit more depth with more detail:

The reasons people read are often closely related to the register in which they need to function. We can distinguish

- reading for general purposes, for entertainment (novels, stories etc.), to inquire into an area of interest (popular science texts, historical articles etc.) or to remain informed about the world (newspapers, general websites etc.).

- reading for specific purposes, in work-related settings (emails, reports, written correspondence, procedures etc.), for study (text books, journals, specialised websites etc.), to pursue a hobby (magazines, newsletters, instructions etc.), for instrumental purposes (instructions, recipes, advertisements etc.)

Our purposes for reading will affect the

kinds of skills we need to deploy but the skills will often be

applicable for both the overarching purposes for reading which we

have. For example, we may use skimming skills when reading a

newspaper article to get the general gist of what is happening and

we may deploy the same skill to determine if a journal article is

likely to provide the data we need in a specific area of work or

study.

Equally, we may read extremely intensively to be certain we have

fully understood a text in both domains, to understand critical

professional instructions, to follow a detailed study text as well

as to understand the motives of a character in a novel or a poet's

use of metaphor.

For the purposes of this essay, I shall focus on reading for

specific information and the ways in which we use our knowledge of

genre-specific text structure and information staging, whether we are

reading for general or specific purposes, to locate the sections of

the text on which we need to focus our attention. I shall also

consider in what follows how we use our knowledge of cohesion and

deixis in texts to understand the author's linking of ideas.

Nothing in the first example is actually wrong but the analysis

is at a low level of detail and precision, simply skating over the

surface.

In the second example, there is greater use of terminology (to be

precise), greater depth of analysis (to point out the overlapping areas)

and better exemplification (to add detail).

The moral for Delta essays is:

- Use terminology accurately and appropriately and do not be satisfied with calling something simply a transaction or an interaction, for example. The reader needs to know that you are aware of overlapping subskills and of the various subtypes hidden within superficial classifications.

- Strive for more depth so it is clear to the reader that you are aware of the issues in the analysis and have researched beyond the level of skills books for classroom use. This will contribute to a sense of your having done proper research.

- Exemplify what you say clearly and comment on your examples to make it clear to the reader that you understand what you are saying. This contributes to the amount of detail you can provide.

Here are two more examples focusing on speaking skills to see how the addition of precision, depth and detail is achieved. The first paragraph is accurate but lacks adequate depth, precision and detail. What follows exemplifies what is required at Delta level.

There are two types of speaking that most students need to know. Firstly, they need to transact in English, i.e., get things done and secondly, they need to interact to maintain social relationships and be part of community.

Traditionally, speaking has been classified

as either transaction, getting things done or interaction, oiling

the social wheels.

This simple dichotomy, while it allows a certain classroom focus, is

inadequate for learners above B1 level because it disguises the fact

that we frequently interact within ostensibly transactional

exchanges and transact within interactional ones. My learners,

preparing for study and work in an English-speaking setting, need

both skills and need to be able to integrate them smoothly. It

is also arguable, as Jones [reference citation] has pointed out,

that all learners above a

certain level of mastery need to combine suasion with social chat

and insert politeness and personal affect language into even simple

transactional encounters.

|

Text types or genres |

This is the second strand of the analysis, whatever your skill focus.

It is here that you demonstrate that you understand the differences

between text types and can analyse them conventionally.

Here, again, are two examples, the first drawing on a lay

understanding

and the other, better one, drawing on a more sophisticated

understanding of generic structure.

A television news bulletin in English will usually follow a predictable format with the top story coming first followed by a description of one or two of the following items to whet the viewers' appetites and will finish with sports reports and, often a lighter item to entertain the viewers.

There's not much wrong with this analysis, so far as it goes but at Delta level, we need much more precision and to demonstrate more awareness. Here's what's meant:

A television news bulletin in English will usually

follow a predictable format with the top story coming first followed

by a description of one or two of the following items to whet the

viewers' appetites and will finish with sports reports and, often a

lighter item to entertain the viewers. This sort of text

follows the staging of an information report: a general statement

and identification of the topic followed by a description organised

into coherent bundles of data (place, time, participants, actions

etc.).

The individual news items usually take this format:

- The main item will usually be introduced in the perfect

aspect or even a present simple tense to lend a sense of urgency

to the report. Typically, expressions such as:

Large crowds have gathered outside ...

An earthquake has struck in ...

There are reports of ...

The president is visiting ...

Viewers who are alert to the use of these tense forms are able to understand the gist of what has occurred and be prepared for the lexis in the report that follows, using predictive listening skills. - What follows will provide the detail and will often be

described in the past simple:

Riot police were deployed in ...

Rescue services were trying to reach ...

The president said, "..."

so alert listeners, primed with this knowledge can focus in particular for behavioural and material process verb phrases and be able to pick out the main points even if some of the detail is not comprehended.

Or, if there is a reporter on the scene, the voice over the film will often be in the present tense (even though there may be a considerable delay between the events and the film being available to view):

This is the scene this morning in ...

The devastation is ...

Let's hear what she had to say ...

Here, listeners need to be more focused on relational process verb phrases in order to understand the connections between the events and states being described. - The story facts having been established, the item will then

often have a coda in which an expert or person intimately

involved in the events will provide a commentary. Here the

viewer / listener needs to be alert to markers of subjective

views in order to be able to distinguish fact from opinion and

speculation. Typical discourse-marking conjuncts,

disjuncts, modal

expressions and copular verb forms are what the viewer /

listener needs to locate here:

Quite possibly, ...

Moreover, ...

... in my view ...

What might be happening is ...

This could develop into ...

In all probability ...

It seems, then, that ...

What appears to have happened is ...

And this analysis is far better in terms of precision, depth and detail. It draws on reading and research, is above the level of a classroom skills book or other texts and shows awareness of not only structure but probable content verb types. The analysis should then be extended to focus on other language items which will allow a fuller understanding such as the use of time and place adjuncts and other adverbials such as prepositional phrases.

|

Subskill analysis |

No Delta essay, properly written, can hope to analyse the whole

of a skill so it is necessary to limit yourself to a subset of

skills that form the core focus (one of which you have in mind

for the lesson you are going to teach).

Here we will not provide an example of an inadequate analysis for

the simple reason that no such analysis will confine itself to the

specific subskills which Delta requires.

Here, then, is an example of skills analysis which focuses on

specific and definable subskills (to do with identifying types of

turn passing and responding appropriately), partly based on one of

the guides in the English for Academic Purposes section of this

site:

Identifying and responding to selection

and constraint in academic settings is a key listening skill which

learners who wish to study in an English-speaking setting need to

acquire. It is also a skill which can, and should, be deployed

in general social settings because the same turn-taking constraints

and opportunities can arise.

The considerations are:

- Selection and constraint

In small groups, i.e., around twenty or fewer, tutors may select the next person to take a turn, either by naming them or by alluding to them in some way. For example:

What is the question we should be asking, John?

Well, we have two people here who have been reading the text. Does either of you have a question?

What do those who will actually do the work want to know?

etc.

Tutors may signal who is to respond to something said by using gaze, focusing on whoever is required to contribute. Being alert to what shifting gaze means is a cultural issue in part but can be taught.

In this case, the learner needs to recognise two important points: not only that it is his or her turn to ask a question or make a point but also that the topic of the question has been constrained by what the tutor is currently talking about. Off-topic questions are not usually welcome.

In other, less academic, settings the same kinds of pattern are observable although, because the power relationships are usually more even, the language selected to realise the function will be different (and usually much less formal). Selection will often be achieved simply through gaze shifting but constraint will normally be verbally achieved. For example:

[Gaze shift] Agreed?

Well, John, which is it to be?

[Gaze shift] What do you think about that? - Constraint only

In lecture settings, a speaker may not have the luxury of selecting questioners because participant names are unknown or because the audience is simply too large.

In this case the speaker needs to rely on constraint alone but the constraint is often signalled explicitly, by the parts underlined in the following examples:

Does anyone have a question about these figures?

Bearing this in mind, does anyone have a question?

Does anyone need to ask anything about the results so far before we go on

Failure to notice question-topic constraint is quite serious because it irritates the tutor / lecturer as well as other participants.

Again, in general, social English settings, the same phenomenon is observable but in this case the listener needs to be alert to other forms of constraint signalling, such as:

What say you to a night out?

I'm thinking about getting a dog

The weather forecast's not too good for tomorrow

in all of which the topic of the next turn has been constrained to going out, dogs and the consequences of the weather, respectively. Failure to notice constraint can often lead to communication breakdown and some frustration in one's interlocutor. - Open-ended invitation

A tutor may do neither of the above and simply signal the fact that a question from anyone on any topic is welcome. This may occur at the end of teaching phases by the tutor falling silent or signalling open-endedness by, for example:

Is there anything at all anyone wants to ask?

Any questions about anything?

etc.

Recognising the lack of topic constraint may be as important as recognising its existence.

In general, social settings, again, lack of constraint and selection is rarer but occurs. This phenomenon is often signalled by turn-passing manoeuvres such as:

Well, anyway, so ... [falling tone and falling volume]

And that's that.

Ah, well, never mind.

|

Learning and teaching problems |

If you have already followed the guide to analysing systems for Delta, the following will be familiar. Click here to skip it and go to the section specifically about learning and teaching problems with skills.

Delta criterion 3b) for the background essay which states that you have to show:

awareness of a range of learning and teaching problems occurring in a range of learning contexts

Actually, you have to do a bit more than show awareness,

you have to be able to describe, and propose solutions (later) for,

a range of problems in a range of

contexts.

Elsewhere, we have glossed this criterion as meaning that you

need to:

- Consider your own setting

- Think outside your own setting to show that you are aware of other possibilities

- Know how other languages work both in terms of systems and skills (not just your own learners' languages)

We'll take these one at a time.

|

Your setting and others |

Settings vary. Here's what you need to consider:

The easiest way to approach this is to contrast and compare your setting with others that you have worked in, imagined, considered or read about.

|

WARNING |

Do not focus in too much detail on the particular class you have in mind to teach for the assignment. Considerations of individuals and classes belong in the Commentary to the lesson plan. Here you must take a broader view of settings in which find yourself and those beyond your own current experience.

Here are some examples of what to write about and what to avoid:

| Do not write | Prefer | because |

| My class is made up of adult professional people who need these turn-taking skills in the work places. | With adult professional learners such

as I am teaching, the need for in-work interactions with

colleagues and superiors is very important because the

businesses they work in use English as the lingua franca.

However, all learners, especially those who live and work or

study (or intend to) in a native-speaking setting need to

master turn-taking skills if they are successfully to take

part in context-specific or more general social

interactions. Turn-taking, even in English, in non-English speaking settings is, however, often constrained not by the norms of Anglophone cultures but by the surrounding culture's norms and this presents difficulties. Additionally, opportunities to practise the skill outside the classroom will be rarer in such cases and this needs to be compensated for in the classroom with more opportunities for practice (see below, section 4.3). |

You are demonstrating that you know

that speaking skills are variable across cultures and you

realise some of the implications of this. You are also referring to pedagogic solutions which you will later discuss. (Do not forget to do so.) |

| I teach my current class for one hour every week so the learners often forget items taught from week to week. | Grammatical and lexical structures need constant recycling in order to be fixed in learners' long-term memories. Some estimates (e.g., Conti, 1997: 243) suggest new lexical items need to be encountered 5 to 8 times to ensure learning. In my setting, in which I only teach my groups for one hour a week, this is particularly challenging because of the gap in time between lessons and the opportunities this provides to forget items taught. On more intensive courses, this problem is less apparent because items can be recycled more frequently with shorter gaps between sessions. (See 4.4 for a proposed solution.) | You are demonstrating awareness of

cognitive and memory constraints in different settings. You have done some research. |

| My school is very well equipped so the use of web-based video resources is appropriate and effective. | In

well-resourced teaching settings, such as I am privileged to

work, the availability of web-based video recordings of

different forms of presentations is a boon in terms of

getting learners to notice the staging analysed above. In less well-resourced environments, however, this is not possible and a constraint on the teacher is imposed which may mean that it is less easy to exemplify the staging and structure of academic presentations. In section 4.5, I propose a solution. |

You are considering other settings outside your own and using teacherly intuition to imagine the teaching difficulty this imposes. |

| Because my students live and work in Sydney they need interactional skills daily. | Learners who

are permanently or temporarily resident in a

native-English-speaking country clearly need these skills on

a daily basis. This is not, however, the case elsewhere and opportunities for practice are concomitantly lower. However, even learners in non-native-English speaking environments may often need to interact with other first- or second-language speakers of English (for example, in countries where English is an official or de facto national language such as it is in many African states). The ability, therefore to recognise when to combine a Response with an Initiation is still something that needs to be taught rather than assumed. |

Because you are getting away from your own setting and considering how the issues might be different elsewhere. Even if you have never taught in the settings you mention, the fact that you have considered them rationally is a strong point to make. |

| My class is preparing for the IELTS examination. | Currently, I

am teaching learners preparing to take IELTS who often fail

to distinguish between these two genres and produce texts

which are unconventional and confusing for the reader. Beyond this setting, however, the IELTS examination is intended to test whether the skills can be deployed in real-life settings so the generic structures I have identified in this essay are still difficult for them to acquire yet important. |

Because you have made it clear that an examination which your, or other, learners are preparing to take is not an end in itself but a means of demonstrating abilities to perform in real-life settings. |

| My Italian learners have difficulties with these verbs because the structures do not exist in Italian. | My current

classes consist overwhelmingly of Italian speakers who, in

common with users of other Romance languages such as Spanish,

Romanian and French often avoid the use of multi-word verbs,

preferring, for example, postpone to put off and collapse to

break down. Speakers of other languages which have something akin to these structures (such as Germanic languages) will be less reluctant to learn and use them. |

You have gone beyond description to consider the implications and the learning / teaching problems and advantages that first-languages structures may give rise to. |

Learning and Teaching problems with skills

You may, as was noted above, choose to consider problems for

learning and teaching simultaneously with the analysis and that is a

legitimate approach. For clarity's sake here, however, we

shall consider them separately but use some of the same examples that we

have used so far for analysis. It is also appropriate in many

skills-focused essays to consider problems for learning and teaching

in tandem with solutions. We shall not do that here but you

should bear in mind that each of the comments below could be

followed by a teaching solution or two.

When you come to discuss learning and teaching problems, you need to

do three connected things:

- Consider your own setting and then

- Think outside your own setting to show that you are aware of other possibilities

- Know how other languages work both in terms of skills. Do not only focus on your own students.

Additionally, if you have restricted your focus by level of

learners, you need constantly to refer to this restriction and make

sure that you don't stray into areas which are clearly too difficult

or too easy.

Here are some (incomplete) examples and, again, they are just that, not models

for all the reasons explained above.

|

Problems with purposeslistening |

It has been asserted with some justification [reference citation] that although the purposes one has for listening to a text are common across all cultures, the skills are not easily or automatically transferred.

- At lower levels in particular, there is often a sense of

needing to understand everything in a text. When this is

not achievable, as it often isn't even for native speakers, I

have noted that learners will often lose the thread and switch

off completely, making the carefully prepared listening text I

am using worthless. For

example:

A text which is authentic and produced by an unprepared native speaker will often contain false starts and back-tracking repairs such as:

Er, no that's not it exactly, it's um, more ...

Such texts tend to demotivate and confuse unless learners have been alerted to the existence of such events. Even then, at lower levels, too much of this kind of things is worth avoiding. Choosing texts which are both at least pseudo-authentic and which do not contain such distractions is challenging.

Learners need, from the outset to know why they are listening. If only the gist is required, as it often is in real life, then they need training in ignoring peripheral data. - Learners who are unaware of the function of simple conjuncts

and disjuncts, such as:

To put it another way, ...

Honestly, ...

will often miss their import. If they do, comprehension can be seriously impaired.

If the learners' purpose is to extract the three main points from a text, missing a conjunct such as in other words ... is a serious matter. - Especially at lower levels, it is inevitable that almost all

listening texts, even contrived ones, will contain blocking

vocabulary unknown to the learners. If the items are

non-essential, they can be safely ignored but learners actually

have no way of deciding whether an item is key or peripheral

unless it is specifically signalled prior to listening.

Again, such items can stop learners in their tracks and

encourage them to disengage from the task.

If the purpose of listening is simply to monitor for a particular item, training in ignoring blocking vocabulary and listening out for, say, a name of a place or a person is important. See below for suggestions concerning how to achieve this.

|

Problems with text typesreading / listening |

Unfamiliar text types can present learners with real reading

problems because the staging and information structuring in them

will be unknown and they will have little information concerning

where critical information is likely to occur.

Cross culturally, too, text structures differ

(as the analysis shows) and the preferred way

of organising texts in English may not be something that learners

from different cultural backgrounds will automatically appreciate.

At all levels, and especially when dealing with a new text type,

readers need some analytical work on where information is likely to

be staged and how the structure of the text may differ from what

they are used to.

For example, in some cultures what is confined to the coda in

English (the writer's reaction to events which have been set out

previously) may conventionally be prefaced to the whole recount so

readers will be looking in the wrong place for the data they need to

understand the text fully.

Academic texts, too, are similarly varied across cultures and in

some the conclusion is the starting, not ending, point for the

writing.

Authenticity is another issue. While it is motivating and

often helpful to use authentic texts, care needs to be taken to

ensure that they are typical of the genre and not quirky and unusual

examples of what people will usually have to read.

Authenticity is of two types and both need to be addressed:

- Text authenticity refers to whether a text is as it was

written for native-speaker readers or whether it needs to be

simplified for the non-native learners of English.

Texts can be described on a cline from truly authentic (unaltered and in the original presentation), quasi-authentic (altered in terms of inserting a glossary of lexis and other learner aids), semi-authentic (based on an authentic model and retaining some semblance of its original presentation) and contrived (specially constructed for pedagogical purposes). - Learner authenticity applies to the uses to which the text is put. A text may be authentic as such but if the use to which it is put is not, for example, as a basis for the analysis of verbal processes and other language forms then the text's authenticity and motivational effect may be compromised.

- At these levels, background distractions and non-ideal

conditions are also problematic. While it is clear that we

need to prepare learners for real-life listening settings, we

need to make sure that listening texts are well recorded and

clear or motivation will fall and frustration increase.

This may mean some loss of authenticity in favour of accessibility and skill development. - The use of audio-only listening texts in the classroom is a problem which can frustrate learners and make the tasks too difficult. It is rare, in real life, and certainly so for most low-level learners, to listen to texts with no visual support. In fact, training learners to use such support is an essential part of the process and this cannot be done in isolation. See below for suggestions concerning how to achieve this.

|

Problems with subskillsspeaking |

The difficulty which is immediately apparent when teaching

speaking skills is the task of breaking the skill down into areas

which can form the focus of the skill development in the classroom

and making the tasks and content of the procedures authentic enough

to simulate real-life communication in speaking.

For example, teaching the skills needed appropriately to recognise

and take turn-passing opportunities in spoken interactions requires

the learners simultaneously to listen for cues and to select

responses which are socially, linguistically and culturally

appropriate.

Distinguishing between

backchannelling routines (which occur within turns)

and opportunities to take up a turn (which occur at transitions) is

also necessary.

Maintaining, rather than merely initiating or responding within

interactions is another issue that needs to be considered.

If learners are unaware of the need both to respond to an utterance

and, within the same turn, to initiate anew, this will soon lead to

the dead-end interactions well known to anyone who has tried to keep

a conversation going single handedly.

It is in this area that breaking subskill of responding and

initiating down is most helpful as a way of getting learners to

notice how conversational structure usually works, at least in

English because languages and cultures differ in the amount of

directness that is allowable and the illocutionary force of

statements which will be understood.

For example, learners need to recognise the four types of

initiation:

- Elicitation: Do you want something to drink?

- Request: Can you do me a favour?

- Directive: Listen. This is vital.

- Informative: I have just got back from Mongolia.

and not all of these will be common to all languages and cultures and perceived as initiations of any sort.

Learners also need to appreciate the three types of response plus new initiation in the same conversational move that are normal and know how they are achieved:

- Preferred:

Yes, please. Thanks very much.

Of course. What can I do for you?

I'm listening. Tell me what's so important.

Have you indeed? What was it like? - Temporised:

Perhaps later. Can we eat first?

Maybe, but I'm busy today. How about tomorrow?

OK, but I think I know what it involves already.

That sounds nice. You must tell me about it later. - Dispreferred:

No, thanks. I have to go now.

Not at the moment. Sorry about that.

Maybe, but I don't have time for this now.

How interesting. Well, I must be off to get my train.

Without breaking the subskill of maintaining conversations down like this, learners may well not appreciate the need in temporised and preferred responses to follow up the response with a new initiation which invites a response plus initiation from the other person.