Hedging and modality in EAP

To get an idea of the importance of this area, compare:

- It is clear that Guru is right when he states ... and we must act on his proposal by ...

- It is probably arguable that Guru may well be right when he states ... and it may be advisable to act on his proposal by ...

Sentence 1. invites the reader try to imagine

all the times when Guru is wrong and also to reject the obligation

to do anything at all.

Sentence 2., on the other hand, is appropriately hedged with

modality, expressing doubt rather than certainty and possibility

rather than obligation. It sounds reasoned and tentative

rather than trenchant and intransigent.

Hedging is often seen as part of what is called cautious writing:

taking care not to be accused of being overly assertive and

dogmatic.

Getting this right is not something that comes easily to writers operating in their first languages and in an additional language is even more difficult so the area needs attention. The failure to modulate assertion appropriately is common especially for inexperienced or non-native writers.

|

How to hedge |

The term hedging is somewhat disparaging, implying

wishy-washiness and the inability to be decisive. Consider

this example from the once-popular British TV series, Yes

Minister. It is the response of a civil servant to the

Minister's simple question

... are

you going to support my view that the Civil Service is over manned

and feather-bedded, or not? Yes or no? Straight answer.

|

Well Minister, if you asked me for a straight answer,

then I shall say that, as far as we can see, looking at it

by and large, and taking one time with another, in terms of

averages of departments, then, in the final analysis, it is

probably true to say that, at the end of the day, in general

terms, you would probably find that, not to put too fine a

point on it, there probably wasn't very much in it one way

or the other, as far as one can see, at this stage. |

This is, of course, an extreme example, designed for comic effect

but it is also clear that a response such as

No, Minister.

or

Yes, Minister

would not have been appropriate, given the fuzziness of the data and

the speaker's wish to be uncommitted.

Hedging of that sort is not appropriate but hedging in academic writing is very frequent and very frequently not satisfactorily achieved either by inexperienced writers in their first language or those struggling to write in academic style in a second language.

In this guide, the focus is on hedging in the statement of a proposition, but the choice of reporting verb, in the case of comment on another's work is also important. For more on how the choice of reporting verb affects the communicated attitude of the writer, see the guide to reporting verbs in EAP (linked below).

|

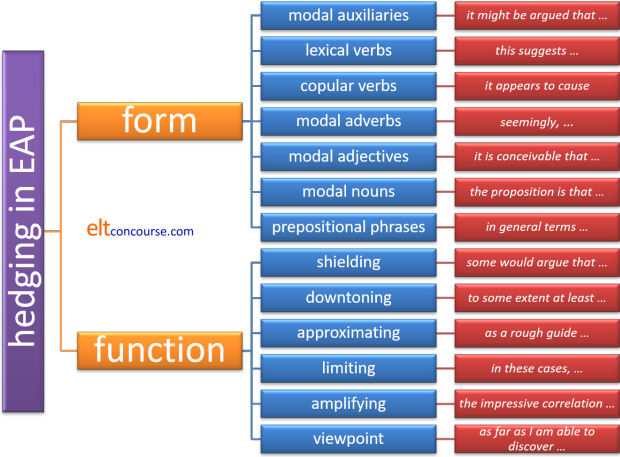

Ways to hedge |

There are a number of ways to classify hedging in academic writing (and arrange a teaching programme). We'll look at two here, one focused on function and one on form, which seem the most useful for our purposes. For more data on vague language, try the excellent book by Channell (1994).

|

Focus on function |

It is sometimes averred (e.g., Hyland, 1996) that hedging has three functions (which may overlap or which may be realised simultaneously). They are:

- reader-oriented function

This is designed to carry the reader with the writer and establish, where possible, some kind of reader-writer interaction. It is typically achieved through the use of personal pronouns such as in:

We could find no evidence that ...

which implies that others might find it or

If we assume that ...

which implies that the reader may assume no such thing or may deliberately go along with the assumption. - content-oriented function 1: the writer

This kind of hedging is designed to shield the writer from criticism by making it appear that it is not the writer who is making the claims. It often involves the use of the passive as in, e.g.:

It has been shown that ...

i.e., I am not showing it

or the use of inanimate agents as in, e.g.:

The evidence suggests ...

i.e., I am not suggesting it. - content-oriented function 2: the data and accuracy

This form of hedging refers to the reliability or otherwise of the data that are being presented. It is often achieved adverbially as in:

It is generally the case that ...

These data approximately parallel ...

This is possibly the result of ...

etc.

The following is drawn from Jordan (1997) who follows Salager-Meyer (1994) and all three of the functions above are exemplified here.

- Shields:

These terms express degrees of certainty or possibility and include a range of pure and marginal modal auxiliary verbs as well as adverbials used to soften the a proposition, i.e., to shield the writer from accusation of too much assertion. This is a writer-oriented tactic.

Examples will be enough here but see below under form for more analysis.- Pure or central modal auxiliary verbs:

The discrepancy could be the result of ...

It might be argued that ...

It may not be the case that ...

It can be argued that ...

Some would argue that ... - Marginal modal auxiliary verbs:

It seems to be the case that ...

This tends to be the result of ...

It is likely to be caused by ... - Adverbials:

This results, quite possibly, in ...

It seems arguably possible that ...

Conceivably, ...

Presumably, ...

- Pure or central modal auxiliary verbs:

- Downtoning, approximating, limiting and (less frequently)

amplifying:

These terms are usually adverbials, often just adverbs. They generally modify adjectives or other adverbs. These are content-oriented tactics often concerning data reliability.

For example:- Downtoners:

The is slightly different from arguing that ...

This is marginally different from ...

This results, to some extent at least, show ... - Approximators:

This is approximately the same number of ...

Roughly, the data can be divided into three sections - Limiters:

In this case, the data are unclear

Under these circumstances the reaction halts - Amplifiers:

It is particularly noteworthy that ...

There are impressively close parallels between ...

- Downtoners:

- Expressions which imply the author's personal viewpoint.

These are reader-oriented tactics endeavouring to involve the

reader in the arguments.

For example:

As far as I am able to discover ...

We have no direct knowledge of ...

We are unaware of any contrary findings in the literature.

A now famous example in the literature is this one concerning the discovery of the structure of DNA:

It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.

(Watson and Crick, 1953, p738)

They could of course have said, It is obvious that ... and we have won a Nobel Prize but that is not the way it's done. - Compounding the hedges. It is possible to heighten the

hedging effect by combining any of the above. For example:

It may, quite arguably, be the case that ...

It seems, as far as we can discover, to be the result of ...

|

Focus on form |

An alternative way to classify how we hedge is to look at which forms we use rather than the (many) functions they perform.

- Modal auxiliary verbs:

As we saw above, of the central modal auxiliary verbs, could, may, might, would are common hedges and, in the negative only, don't/doesn't have to is usable. The three marginal modal auxiliary verbs exemplified above also play a role. The modal would is often used to distance the writer. Compare, for example:

We argue that ... (assertive)

vs.

We would argue that ... (tentative)

Modal auxiliary verbs not used in this way, or in academic writing generally, include should, must, ought to and, in the negative couldn't and can't (have). These make the writer seem overly assertive and are avoided. For example:

This must / can't / couldn't be the result of ...

We should focus on ...

It ought to be clear that ... - Other verbs:

These are often copular verbs standing in place of the too-assertive, be. Compare, e.g.:

This is the result of ...

vs.

This appears to be the result of ...

The outcome is that ...

vs.

The outcome appears to be that ...

Other verbal processes using lexical or main verbs are also common. For example:

This suggests (i.e., I suggest)

This leads to the conclusion ... (i.e., I conclude)

This figure represents a large increase over the previous year's (i.e., is a large increase)

In general, the present-simple use of the verb be sounds overly assertive in many cases. - Modal adverbials. See above for other examples.

Here are some more:

It is apparently the case that ...

Seemingly, the respondents have taken the view that ...

Ostensibly, this is a reason for concern

Outwardly, the materials are ...

From the evidence, it seems the case that ....

From this limited evidence, ...

In this case, ...

etc. - Modal adjectives, often used predicatively after a complex

nominalisation. For example:

A probable outcome is ....

A new and more complex model of the phenomena is possible

One quite likely outcome is ...

More serious and longer-lasting consequences are imaginable

It is conceivable that ...

The results so far are promising

etc. - Modal nouns formed from these adjectives are an alternative.

For example:

One possibility is that ...

A reasonable assumption might be that ...

Our hypothesis is that ...

A postulation we can put forward is that ...

One proposition is ... - Prepositional phrases, acting often as adverbials, can also be

used to soften the assertive nature of a proposition. For

example:

This is, as far as we can see, ...

By and large, the process can be described as ...

If one looks in terms of averages ...

At this stage, it is difficult to predict ...

In general terms, ...

Summary (with a few examples)

|

Teaching and learning issues in EAP |

As with much else in English for Academic Purposes, the situation

is complicated and the range of hedging terms is too great to

present easily. A piecemeal approach over a series of lessons

using elements of the analysis above is advisable.

You can take a function-to-form approach or a form-to-function

approach but:

- A function-to-form approach works best if you are focused on getting learners to produce suitably hedged expressions because they know (or should) what exactly it is that they want to express and need you to provide appropriate realisations of the functions.

- A form-to-function approach works best if you are focused on enabling learners to unpack the hidden messages in what they read because the forms are easy enough to spot (if you have primed their noticing) and then they can focus on what the author's intention is.

- Identification, noticing in other

words, often precedes any productive activity. An example

might be to get learners to note the differences between these

two paragraphs and speculate together (with you if need be) on

the reasons for the differences and the writer's choices.

Paragraph A Paragraph B It is quite obvious to all of us that the excessive use of private cars in cities is very damaging to everyone's health and must be curbed. The best way of doing this is to charge drivers for the luxury of using inner-city roads, especially at peak times. The positive experience of London should be considered because that was clearly extremely successful and must be emulated by other cities which undoubtedly have the same terrible problems. Many would argue that what some see as the excessive use of private cars in cities is possibly damaging to health and might usefully be curbed. A proposed way of doing this is to charge drivers for using inner-city roads, especially at peak times. The experience of London might be considered because that was arguably successful and could be emulated by other cities which may have the same problems. - Another noticing / awareness raising

procedure is to present learners with a range of possible ways

to express a thought and get them to rank them in terms of their

assertiveness. They then need to identify the language use

which led them to their conclusions. For example:

Rank the following from most to least assertive (A to F):

- cars obviously can sometimes create what some see as harmful pollution

- it is often asserted that cars create harmful pollution

- it is often asserted that cars may create harmful pollution

- it is often asserted that cars create harmful pollution in most circumstances

- it is often asserted that cars create harmful pollution in some circumstances

- cars are polluting monsters which should be banned forthwith

- Learners can also be presented with

very assertive statements and asked to make them more tentative

or vice versa. For example:

Fill in the gaps in this table:

Tentative Assertive It is conceivable that the material might be robust enough. → The material is obviously extremely robust. → I am convinced that this is the only possible solution. A possible analysis is that some commentators have tended to see this approach as being perhaps too harsh → → We must not accept these figures at face value. - A reasonable approach to the area is

to focus on one function and one or two forms (or realisations

of the functions) at a time. This will depend greatly on

the level of the learners.

- At lower levels, simple adverbs,

lexical or main verbs and modal auxiliary verbs are approachable:

might instead of must

arguably instead of clearly, obviously or certainly

I suggest rather than I think

etc. - At higher levels subtler

gradations of sense can be introduced:

At this stage we can be reasonably confident that ...

instead of

Now we know

It seems possible to conclude, at least for now, that ...

rather than

Obviously, ...

etc. - A possible ordering of a mini-syllabus

in the area is:

By function By form shielding pure or central modal auxiliary verbs

marginal modal auxiliary verbs

adverbialsdowntoning adverbials

prepositional phrases

modal adjectives

modal nouns from adjectivesapproximating adverbials

prepositional phrasesamplifying adverbs modifying adjectives limiting adverbials

prepositional phrasesviewpoint expression avoiding use of first person

alternatives to be, think, conclude etc.combining the above combining the above

- At lower levels, simple adverbs,

lexical or main verbs and modal auxiliary verbs are approachable:

- Learners can, if procedures such as these are followed, be persuaded to return to and edit their own texts or to deploy a range of hedging devices in what they write.

| Related guides: | |

| in-service skills index | for more on skills work |

| reporting verbs in EAP | for more on how these verbs can be used to lower assertiveness and hedge citation |

| epistemic modality | for what hedging is all about |

| index | the EAP index |

| modality index | for a range of choices of where to go next and what to consider |

References:

Channell, J, 1994, Vague Language, Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Hyland, K, 1996, Writing without conviction? Hedging in Science

research articles, Applied Linguistics, 17 (4), pp. 433-454

Jordan, RR, 1997, English for Academic Purposes,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Watson, JF and Crick, FHC, 1953, A Structure for

Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid, Nature 171: 737-738 available online

at: http://www.nature.com/nature/dna50/watsoncrick.pdf