The genitive in English

|

What is the genitive case? |

The genitive is a case which is usually understood to refer to ownership of something. As we shall see, however, a better definition encompasses rather more and it is a case expressing at least:

- possession

- source

- origin

- description

Usually in English, case is unmarked so, if you have followed the guide to case on this site, you will know that although these sentences express case:

- The man kissed the woman

- The woman kissed the man

In English, we only know who did what to whom by the order of the words.

The subject comes first in both sentences so we know that is the doer of

the action. The object follows the verb so we know that is the

receiver of the action. If we reverse the order, we reverse the

sense.

In many languages, the nouns (man and woman) or the article (the)

would be identifiable as referring either to the subject or the

object of the verb. They would be described as nominative (the

subject) and accusative (the object).

Many will assert that English does not, for this reason, have a

case-structured grammar and, apart from the use of the pronoun

system, that is generally true.

The exception in English is that the genitive case is marked and it is marked in four ways:

- By the inclusion of an 's' preceded or followed by an

apostrophe as in, e.g.:

The woman's property - By a periphrastic expression with the preposition of

as in:

The property of Mrs Smith - By a possessive determiner as in:

Her property - By a possessive pronoun as in:

The property is hers

Modern English does not inflect any other item to show the genitive

case so the object noun is unmarked (the word property and the

article the remain unchanged throughout).

Other languages will mark the noun and the article and may often inflect

other items such as any adjectives in the same way to show the genitive

(and often other cases).

The guide to case identifies at least nine other common cases in a range

of languages and there are more that it does not consider.

|

The genitive in English |

| with his feet on her case |

The genitive in English is often called the possessive case but

the situation is a bit more complicated as was stated at the outset than just

indicating possession.

An example is

The reaction of the man to the woman's kiss was unexpected.

This tells us whose reaction and whose kiss we are talking about.

It also exemplifies the inadequacy of talking about possessives in

English because it is not likely that we see a reaction or a

kiss as

something one possesses.

We have here two forms of the genitive:

- the inflected form: inserting the 's or s' at the end of the noun (the woman's kiss)

- the periphrastic form: using the preposition of to show

the relationship (the reaction of the man). In fact, other prepositions, such as

from and by are possible. For example:

The man from the government called

The examination by the doctor

but of is the one of choice.

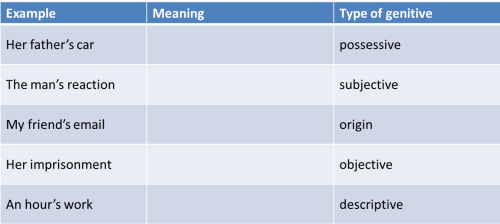

Here are five examples of the use of the genitive in English. Can you fill in the middle column with what relationship between the nouns the case is indicating? Click on the table when you have an answer.

(Source: Quirk et al, 1972:193)

So the genitive in English has four other uses in addition to showing possession. Other languages will work differently so you need to use the analysis to make sure you are presenting and analysing things accurately and not allowing your learners to believe that the form in English is just to do with ownership.

Even the possessive use can be subdivided and some languages will

use a different form to distinguish between, for example:

John's car

and

John's weight

because in the first case the possession is not absolutely fixed and

in the second it is. The distinction may be described as

alienable vs. inalienable, respectively. There is a

little more on this below because the way that possession is

expressed in English is also affected by the concept of

alienability.

|

The five meanings |

At the outset, we identified four possible types of genitive in English and now we have added a fifth, the objective use of the genitive. Here they are, explained with examples:

|

1. The possessive genitive |

If we can paraphrase a statement using the verb have, we

are normally talking about a possessive use of the genitive.

Even here, however, the concept of possession is not appropriate in

all cases.

It is clear that in:

That's the child's toy

The possessive is natural because we can rephrase the clause

with

The child has / owns that toy

We cannot, however, easily rephrase:

The vicar's brother

as

The vicar owns a brother

although

The vicar has a brother

is a natural rephrasing.

Equally

Jupiter's orbit

is not the equivalent of

Jupiter has an orbit

There is one more important distinction to be made here and it is a distinction that many languages rely on quite heavily: alienable and inalienable possession. Briefly:

- Alienable possession refers to objects that can change

ownership such as computers, cars, houses, books etc.

In this sense, we can use verbs like own and

possess as in, e.g.:

John owns a large house

She possesses three laptops

etc.

We can also use the verb have in this sense:

John has a large house

She has three laptops - Inalienable possession refers to entities which cannot

change hands sensibly so we have, for example:

John has a bad leg

She has beautiful hair

Mary has three brothers

etc.

In this sense, of course, verbs such as own cannot be used so we do not allow:

*John owns a bad leg

*She owns beautiful hair

*Mary possesses three brothers

Some languages, as we noted, make more of this distinction and will not allow verbs to cross the divide.

|

2. The subjective genitive |

The subjective genitive refers to the nature of the subject of a

clause. For example:

John's disappearance

can be rephrased as

John disappeared

and

Mary's disagreement

can be

Mary disagreed

It is clear in this case that we are not talking about

possession in any sense but about the subject of the imagined verb.

There is no useful way that we can attribute ownership to either the

disagreement or the disappearance in examples like this so calling

this a possessive at all is misleading.

|

3. The genitive or origin |

Here we are considering the source of the noun. For

example:

The court's decision

can be paraphrased as

The decision the court produced

and

His uncle's telephone call

clearly is a call that originated from his uncle.

Again, possession per se plays no role.

|

4. The objective genitive |

The second of these uses of the genitive, above, referred to the subject but this type

of genitive refers to the object of the clause that we can make by

paraphrasing the expression. For example:

The arches are the bridge's support

can be paraphrased as

The arches support the bridge

and

Susan's arrest

as

Someone arrested Susan

No sense of possession is present.

We will note here and below that some ambiguity can arise concerning

whether a genitive refers to the subject (type 2., above) or the

object (this category). For example, in:

The doctor's examination

most will assume the subjective use and be able to paraphrase

this as

The doctor examined

However, in:

The man's investigation

it is unclear without context and co-text whether the correct

paraphrase is:

Someone investigated the man (an objective use)

or

The man investigated something or someone (a

subjective use)

|

5. The descriptive genitive |

In this case, paraphrasing usually means a use of some kind of

adjectival, classifying or post-modifying expression. For

example:

A Master's degree

refers to the type of degree and could be rephrased using a

classifier as

A post-graduate degree

and

The teachers' room

as

The room set aside for teachers

No sense, except very marginally, of possession is involved

although the second example could be paraphrased as

The teachers have a room

but not as

The teachers own a room.

|

The flexibility of the genitive in English |

The following draws on Huddleston et al (2002:474) to

demonstrate the large range of meanings that the genitive in English

can signal. It is important to do so because other languages,

most in fact, do not share the structures and prefer to express the

relationships encoded by the genitive in English in other ways.

The examples here all use the genitive 's construction but

that need not be the preferred choice for all the examples.

The left-hand columns contain example expressions and the right-hand

columns are

used to illustrate, not define, the meanings encoded by the genitive structure.

| Example | Signalling | Example | Signalling | |

| John's black hair | a physical attribute | her father's first book | human creation | |

| Peter's elder brother | a blood relationship | her father's obituary | topic | |

| Jean's husband | a non-blood relationship | her father's illness | suffering / undergoing | |

| the woman's boss / deputy | a hierarchical relationship | the room's furnishings | containing | |

| the boy's friends | a social relationship | last year's fashion | the time of | |

| Mary's team | membership | the element's radiation | natural creation | |

| the company's rehearsal | performance | the building's windows | constituent part | |

| Fred's house | ownership | the computer's monitor | associated part | |

| John's embarrassment | emotional state | the argument's origins | cause | |

| her father's letter | origin | the war's consequences | result |

As you see, they are extremely variable and not confined to the

five categories we have already identified although many may be

considered subsets of those.

It is perilous to assume either that the meanings will be encoded in

similar ways in other languages or that the meanings will be easily

grasped by learners of English. Some will, some won't.

|

The four marked forms |

We identified above the four forms which signal a genitive and they were:

- Possessive determiners

- Possessive pronouns

- The genitive 's' (often called the Saxon genitive)

- The of genitive (a periphrastic formulation)

Forms 1. and 2. can be handled together because they refer to the same kind of issue.

The genitive determiner and pronoun system is defective in English as this table shows:

| Person, gender and number | possessive determiner | pronoun |

| First person

singular (all genders) |

my | mine |

| First person

plural (all genders) |

our | ours |

| Second person

(all genders, all numbers) |

your | yours |

| Third person singular masculine | his | |

| Third person singular feminine | her | hers |

| Third person singular neuter | its | - |

|

Third person plural (all genders) |

their | theirs |

The system is defective in comparison to many other languages because:

- Only the third person singular has any gender marking and even that is defective because the same word (his) serves as both a determiner and a pronoun.

- The second person shows no distinction for number, familiarity or gender with only one determiner (your) and one pronoun (yours).

- There is no pronoun for the third person singular neuter at

all. We cannot say, in English:

Where did that screw come from?

*It is its.

Many other languages are a lot more sophisticated (and

complicated).

For example, French shows a distinction in determiners (ma

or moi) depending on the gender of the noun but has the

same form (à moi) for the pronoun. French, too,

distinguishes between forms of the second-person pronoun depending

on familiarity (the tu-vous distinction) and German does

much the same also having a plural form of the familiar which French

lacks (euer).

Other languages may have separate forms for various genders, levels

of familiarity and numbers and some are very complex indeed with

lots of case, gender and number inflexions or separate forms.

Comparatively, English is very simple but the distinction between

the pronoun and determiner forms can create difficulties as does the

lack of certain pronouns and determiners.

|

The two main genitive constructions |

|

the contents of the flask the flask's contents |

The lack of complexity in the pronoun and determiner system is a bonus for learners but it is made up for by the difficulty associated with a peculiarity almost unique to English, namely, two ways to show the genitive on nouns: the Saxon genitive 's' and the of-structure.

|

Which form to use? |

English is quite unusual in having two genitive forms to call on and most languages make do with just the one. Deciding which to use is not at all easy.

|

Task: Which of the following are normally not acceptable? Jot down the letters (a to x) of the ones you wouldn't accept. Click here when you have a list. |

|

|

|

|

It is possible, of course that we will disagree. However, most people would suggest that the following are, if not wholly unacceptable, then at least slightly odd or stilted:

| a. the car's cost c. the pencil of Mary h. the ears of the dog p. the work of a day |

r. the ambition of my life t. the chair's legs v. the toys of the children w. the house's roof |

|

Why should this be? |

Traditionally, the explanation is that we use the periphrastic

structure with of for inanimate objects and the 's or

s' structure with animate ones but that is not at all the end

of the story.

If the rule were so simple, then London's parks

and gardens, a day's work and the country's future would

all be wrong.

|

Task: Can you figure out a better set of rules? What do you tell your learners? Click here when you have something noted down. |

- Lower animals and inanimate objects

With so-called 'lower' animals and wholly physical inanimate objects, we prefer the of-structure. If we always select this one for such nouns, we will very rarely be wrong. We can sometimes say:

the bacterium's nucleus

but we will never be wrong if we prefer

the nucleus of the bacterium.

Many people will accept, for example:

the street's position

the car's battery

the room's decor

the book's topic

the building's design

and thousands of other inanimate objects with the 's genitive in use.

However, it is less likely that the same people would accept:

?the chair's leg

?the window's frame

?the screen's brightness

?the house's design

and many more.

Quirk et al (1972:201) simply conclude, slightly despairingly:

one of them is, however, generally preferred for reasons of euphony, rhythm, emphasis, or implied relationship between the nouns

but that is not a useful rule to give to a learner of English, of course.

Because the area is so variable and unpredictable the best advice for learners is to stick to the of-formulation unless and until you have heard a native speaker use the 's formulation.

See also below in the short section on avoiding the genitive by using noun adjuncts. - People

With personal names, nouns for people, nouns for collections of people and higher animals we prefer the inflected form. It is possible to have:

the government of the country

but if we prefer

the country's government

we won't be wrong. If we prefer

*the pencil of Mary

however, we will be wrong.

(A small quirk here concerns the use of whose. Questions with whose, although they refer to the genitive case, cannot be answered with the of-formulation. For example,

Whose policy is it?

can elicit:

The government's

but cannot be answered with

of the government.) - Times

With nouns for time spans we prefer the inflected, 's or s' form:

a week's money

two years' hard labour

today's headlines

an hour's wait

etc.

In all these cases, most would find the of-construction strange and many would reject something like:

?*the work of an hour

outright. - Places

There's a range of intermediate cases where both forms are equally acceptable. Nouns in this category include geographical entities.

Germany's population / the population of Germany

nouns relating to places

the restaurant's garden / the garden of the restaurant

and some nouns referring to human activity

the influence of philosophy / philosophy's influence

the novel's plot / the plot of the novel

However, the of-structure is always acceptable with these sorts of nouns. - Apposition

There is, however, no choice of structure when a noun phrase is set in apposition to another, both referring to the same entity (i.e., they are co-referential).

We may, for example, allow both:

Jane Austin's novels are greatly loved

and

The novels of Jane Austin are greatly loved

but when apposition is used we can only allow the periphrastic form as in:

The novels of Jane Austin, the Victorian writer, are greatly loved

and we do not allow:

*Jane Austin's, the Victorian writer, novels are greatly loved.

We can, however, circumvent the rule in very informal language with:

?*Jane Austin, the Victorian writer's novels are greatly loved

but that is better avoided and many would not find it acceptable at all. - Markedness

When both forms are acceptable, as is often the case, one may be more marked than the other so there is, in fact, a difference between:

The building's fourth floor

and

The fourth floor of the building

The inflected structure emphasises the building as being the point of reference and the periphrastic form emphasises the floor.

This also occurs with purely possessive meanings so:

My neighbour's house

emphasises the owner and

The house of my neighbour

emphasises the house. - Ambiguity

One function of the genitive is described in the table above as objective insofar as it refers to the object of a verb. One example given there was:

the woman's imprisonment

in which the woman is the object of the imprisoning and both the 's form and the of-formulation are acceptable so we can equally have:

the imprisonment of the woman.

However, there are times when it is necessary to use the of-formulation or another prepositional phrase to avoid ambiguity.

For example:

the man's investigation

could mean:

the investigation into the man

or

the investigation done by the man

If the former is intended then

the investigation of the man

is preferred (the man was investigated, not the man did the investigation).

Compare, too:

the doctor's examination

with

the examination of the doctor

in the first of which the doctor is the subject who did the examination and in the second of which, the doctor is the object of examination.

The rule of thumb is to reserve the of-formulation for objective genitives and keep with the 's formulation for humans in subjective genitive expressions whenever there is a need to avoid ambiguity.

(You should also note a few fixed-phrase oddities: a stone's throw, at my wits' end, your money's worth, in arm's reach, at arm's length etc.)

|

The double genitive |

Double genitives, with a marker attached to more than one entity

are reasonably common and uncontroversial. We can

encounter, therefore:

John's parents' car is parked outside

and so on.

This can even apply to three entities as in:

John's parents' car's battery is flat

but that is the limit cognitively with which most people can happily

deal.

However, a double genitive applied to only one entity is

something on which generally speaking grammarians will frown.

It is averred, therefore that:

This is a friend of Peter's

That is a book of my brother's

or

Piglet is a friend of Winnie the Pooh's

are malformed and should be rephrased as

This is Peter's friend

That is a book of my brother

Piglet is is a friend of Winnie the Pooh

and in any other way that allows only one genitive marker.

They are, nevertheless, quite commonly heard and go by unremarked,

despite the obviously flawed nature of the second redundant genitive

marker.

In fact, the double genitive marker is not only common and

unremarkable, it is obligatory with certain structures.

There is, for example, no way in which:

She's the only friend of theirs who came to the wedding

where the genitive marking occurs once with the of-formulation

and once more with the use of the possessive pronoun theirs,

can be sensibly rephrased to avoid the issue.

It cannot, for example be replaced with:

*She's the only friend of them that came to

the wedding

or with:

*She's the only their friend who came to the

wedding

This use of an obligatory double genitive is confined to human

referents for the marker but it is unavoidable and unavoidably

redundant.

We may be right to caution against the use of the double genitive

with non-human referents as in:

That is book of the library's

because that is easily rephrased without the double marking but for

human references, no such prohibition can be sustained.

Had the English language a powerful cultural overseer such as the

Academie Francaise, the issue would doubtless have been resolved in

favour of its avoidance.

You may see the double genitive described in other terms as the

pleonastic genitive, oblique genitive or post-genitive.

Whatever it is called, it remains a grammarians' itch.

|

Avoiding the genitive: noun adjuncts |

| The bull fight or corrida de toros |

In many languages, it is exceptional or impossible to use a noun

to modify another and that's why the Spanish translation of bull

fight uses the genitive preposition de to make

corrida de toros. Not so in English.

We saw above that although many genitive constructions are

permissible using the 's / s' formulation with inanimate

objects, many are clumsy and produce unacceptable phrasing, so while

most will accept

the book's cover

the picture's frame

the door's colour

and so on, other uses of the genitive inflexion are much more

questionable and they may include:

?the desk's leg

?the window's pane

?the computer's keyboard

and so on. In these cases, there is a choice to be made

and one option, as we saw, involves using the of-formulation

and constructing:

the leg of the desk

the pane of the window

keyboard of the computer

etc. However, these sorts of expressions are also

perceived by many as somewhat clumsy.

The other option is more elegant and simply involves using the noun

to classify or categorise the other so we can make:

the desk leg

the window pane

the computer keyboard

and so on.

This use of nouns as classifiers is referred to as making them noun

adjuncts and you may find them referred to as attributive nouns,

qualifying nouns, noun (pre)modifiers or apposite nouns. This

is an elegant solution which needs to be taught because many

languages simply cannot do it. That may partly explain why

mistranslations abound in signs directing English speakers to

The Port of Calais or The Airport of Kalamata.

Thus it is that we see, for example:

Luton Airport

rather than the clumsier The Airport of Luton or

Luton's Airport

There is more on the use of noun adjuncts in the guide to partitives

and classifiers, linked below.

|

Phrase modification: the phrasal possessive |

| The man in the park's dog |

English is, again, unusual in allowing the genitive 's'

structure to be appended to a whole noun phrase after the

post-modification. We allow, at least in speech, therefore:

The woman in black's husband

The girl in room six's note

The people from Austria's complaint

and so on.

This is not immediately intuitive for most learners.

The same constraints concerning the types of nouns which are allowed

with this construction apply so many would not accept:

?The table in the corner's leg

To avoid the informality of such expressions, the alternative

genitive construction is preferred in writing and formal speech:

The husband of the woman in black

The note from the girl in room six

The complaint by the people from Austria

but this breaks the rule above concerning the naturalness of using

the 's' genitive with people.

The issue is one of phrase constituents and, because we perceive the

whole of the modified noun phrase as the subject or object of the

verb, we avoid, for example:

*The woman's in black husband

because it is nonsense so we prefer:

The woman in black's husband

and also

The man's dog in the park

because that ascribes the modification to the wrong noun and

implies that the man is not in the park so we would also prefer:

The man in the park's dog

It can also lead to

absurdity as in:

The woman's eyes in the corner

|

Warning: when of is not a genitive signal |

The prepositional phrase of + noun is not, of course,

always a marker of the genitive. In the following examples, no

genitive is intended and no replacement with 's, however

unnatural sounding, can be accepted.

the City of London

the news of the birth

the love of money

a man of integrity

memories of childhood

etc.

What is happening here is that the noun is being post-modified by a

prepositional phrase describing an attribute and no genitive sense

can be assumed.

For more examples of how a prepositional phrase can be used to

post-modify nouns and noun phrases, see the guide to noun

post-modification, linked below. In that guide, the genitive

of-structure is considered as just one of a range of eight

post-modifying prepositional phrases.

Another frequent occurrence of of + noun phrase is in

partitive expressions and assemblage terms. For example:

a rasher of bacon

a pane of glass

a flock of sheep

a shoal of fish

and in none of these cases is there any sense of a genitive case

structure.

|

Pronunciation of 's and s' and of |

If learners have already mastered the pronunciation of the third-person s and the plural s, then this will not be problematic because the same rules apply:

- Following /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/ or /dʒ/, the

pronunciation is /ɪz/. E.g.:

the class' teacher (/ðə.ˈklɑː.sɪz.ˈtiː.tʃə/)

the disease's symptoms (ðə.ˌdɪ.ˈziː.zɪz.ˈsɪmp.təmz/)

the fish's habitat (/ðə.ˈfɪ.ʃɪz.ˈhæ.bɪ.tæt/)

the luge's rules (/luːʒɪz.ruːlz/)

the church's position (/ðə.ˈtʃɜː.tʃɪz.pə.ˈzɪʃ.n̩/)

the judge's decision (/ðə.ˈdʒə.dʒɪz.dɪ.ˈsɪʒ.n̩/)

- When following any other voiceless consonant, /p/, /t/, /k/,

/f/ or /θ/, the pronunciation is /s/.

the ship's captain (/ðə.ˈʃɪps.ˈkæp.tɪn/)

the government's decision (/ðə.ˈɡə.vərmənts.dɪ.ˈsɪʒ.n̩/)

the pack's leader (/ðə.pæks.ˈliː.də/)

the staff's attitude (/ðə.ˈstæfs.ˈæ.tɪ.tjuːd/)

a month's work /ə.ˈmənθs.ˈwɜːk/)

- Otherwise, the pronunciation is /z/. E.g.:

David's car (/ˈdeɪ.vɪdz.kɑː/)

Japan's population (/dʒə.ˈpænz.ˌpɒ.pjʊ.ˈleɪʃ.n̩/)

the computer's memory (/ðə.kəm.ˈpjuː.tərz.ˈme.mə.ri/)

John's house (/ˈdʒɑːnz.ˈhaʊs/)

the paper's editor (/ðə.ˈpeɪ.pəz.ˈed.ɪt.ə/

etc.

The preposition of is almost always weakened to /əv/ and

may even in very rapid speech, especially between two vowels, be simply /v/ so we get, e.g.:

the opinion of the majority

(/ði.ə.ˈpɪ.nɪən.əv.ðə.mə.ˈdʒɒ.rɪ.ti)

the navy of Australia (/ðə.ˈneɪ.vi.vɒ.ˈstreɪ.liə/)

| Related guides | |

| pronouns | for a guide to the pronoun system of English (which is case marked) |

| case | for a guide to a wider area |

| classifiers and partitives | for more on noun adjuncts |

| noun post-modification | which considers the genitive of-structure in the context of other noun post-modifying structures |

References:

Chalker, S, 1987, Current English Grammar, London: Macmillan

Campbell, GL, 1995, Concise Compendium of the World's Languages,

London: Routledge

Huddleston, R and Pullum, GK et al, 2002, The Cambridge

Grammar of the English Language, , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Quirk, R, Greenbaum, S, Leech, G & Svartvik, J, 1972, A Grammar of

Contemporary English,

Harlow: Longman