Pre- and post-determiners

If you have followed the guide to determiners on this site, you will probably have noticed that determiners rarely co-occur. We cannot, for example, have:

- *the a car

- *that the man

- *my the house

etc. This restriction, incidentally, does not exist in a range of other languages.

However, there is a distinct class of determiners which function

to modify other determiners. What is included in this

class is a matter of some disagreement. The approach taken

here is to consider first which determiners most authorities will

agree can function as pre-determiners and then to consider some more

marginal cases which, at least for teaching purposes, can be analysed

in the same way.

Later in the guide, we will get to a brief consideration of

post-determiners.

In what follows, we will class the zero article as a determiner. In an expression such as:

All luggage must be weighed

it appears that the word all is the only determiner

present. However, because luggage is a mass noun it

can be analysed as being preceded by the zero article. Then

the structure is

all + zero article [Ø] + mass noun

and all may be classed as a pre-determiner.

Missing from the following is any mention (apart from here) of

what are called restrictive or exclusive adverbs. They

include, for example:

That just

the thing I need

It's only a small spider

She is solely the person in

charge

He's merely

the assistant

It appears to be

simply a question of

money

and are excluded here because they are considered in the guide to

adverbs. These adverbials refer to the whole verb or noun phrase and

are not, strictly speaking, pre-determiners. They are

sometimes called limiters.

In many analyses, the list of pre-determiners is very limited and includes only:

- all, both, half

- multipliers: double, twice, eight times etc.

- fractions: a third, one quarter, a thousandth etc. (but, note, not half)

We will be slightly more adventurous than that but will note when what we include in this guide is not an analysis shared by everyone.

It is also worth making it clear now that only one pre-determiner per phrase is permissible. In other words, these items are all mutually exclusive and cannot co-occur.

|

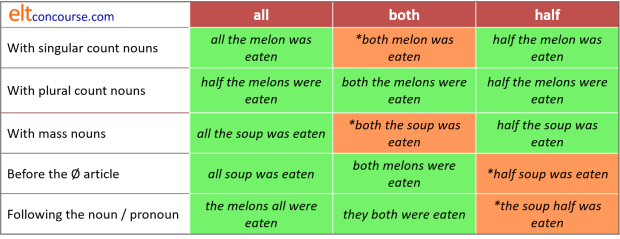

all, both, half |

These pre-determiners function in slightly different ways.

- With singular count nouns we can use half and all but not both

- For example:

half a loaf is better than none

half this job will be done soon

all my house has been decorated

he waited all that day

but not:

*both my job was done - With plural count nouns we can use all three pre-determiners but half cannot be used with the zero article

- For example:

half those oranges are rotten

both the children came

all the men went home and stayed there

all lions are unpredictable

both (the) dogs are friendly

but not with the zero article:

*half people arrived

*half trains are always late in my country

The predeterminer (or determiner) both refers to dual entities only. - With mass nouns we can use half or all but not both. Additionally, only all can be used before the zero article

- For example:

half my money is already gone

all the information is not needed

all luggage will be returned at baggage reclaim [zero article]

but not:

*half chocolate is gone

*both the sugar is gone

|

notice |

- We cannot use all, both or half before

other quantifier determiners:

- *half every, *both neither, *all each, *half some, *both no, *all enough are all disallowed for obvious reasons of the meaning they carry.

- There is an informal use of half in which this

rule can be broken:

I don't have half enough time to do this

but this only works with enough.

- These three pre-determiners have alternative of-constructions

such as:

all of the time

both of the boys

half of the house

etc.

Although this is an optional structure when the noun is being determined, it must be used when we are pre-modifying a pronoun so we have:

all of it was wasted

both of them came

half of it was used

half of them were drunk

but not

*both them arrived

*half it was rotten

*all them were sold

etc.

Moral: if in doubt, use the of structure. - All three can act as pronouns (pro-forms) rather than

determiners in their own right, slightly formally in some views:

All arrived in time

Both broke immediately

Half was rotten - Only all and both can follow the noun or

pronoun they determine:

the ladies all arrived late

the children both cried

They all complained

but not:

*the cake half was eaten - The pre-determiner both is not so much plural as dual (a concept taken much further in some languages). It shares this characteristic with the determiners neither and either.

- Both also functions adverbially as an additive and

equaliser and

is considered in the guide to adverbs, linked from the list

below. One example will do:

John is both a good manager and an approachable boss

Here's a summary of these three:

|

multipliers: double, triple, quadruple, once, twice, three times, four times ... |

These are less complicated and can occur:

- With singular count nouns, plural count nouns and mass nouns

- twice the price

double that amount

three times the weight

20 times his ability - double the chairs will be

needed

quadruple the effort

etc. - Before the determiners a, per, every, each, multipliers can form distributives

- once every term

three times a year

six times each month

20 times per century

|

notice |

- There is no parallel of-construction so we cannot

have, e.g.:

*double of the work

*three times of his height - None of these pre-determiners can follow the noun or pronoun

so we can't have, e.g.:

*the amount three times

*the price quadruple of the other - There are some arguably old fashioned or rare terms which it may be best to avoid except at the highest levels including, e.g., thrice, sextuple etc.

|

fractions: one-sixth, two-fifths, three-quarters etc. |

These, too, are fairly straightforward but it is worth noting some things:

- All these expressions have alternative, parallel of-constructions

and these are usually preferred. Some of the examples

without of in the following sound strange to most

native speakers:

one-third the money > one-third of the money

sixth-sevenths the time > sixth-sevenths of the time

three-quarters the effort > three-quarters of the effort

five-eighths the distance > five-eighths of the distance

etc. - The pre-determiner half is not included in this

section because it has some characteristics which are not shared

by fraction pre-determiners, especially when it comes to the use

of the of-construction with count nouns:

We can have:

half of those vegetables are rotten

half those vegetables are rotten

one third of those vegetables are rotten

half my work has been wasted

one quarter of my work has been wasted

but not

*one third those vegetables are rotten

or

*one quarter my work has been wasted

etc. because only half can be used without the of-construction before demonstrative and possessive determiners. - Some fractions in English are a real challenge to pronounce

and spell. Consider particularly sixths,

eighths, sixtieths (respectively, /sɪksθs/, /eɪtθs/,

/ˈsɪk.stɪəθs/) etc.

Many languages simply do not allow consonant clusters such as /ksθs/ and speakers of those languages (Japanese and Arabic, for example, as well as some south-east Asian languages) will find it very hard to get them right.

Speakers of Slavic languages will have less difficulty because those languages routinely contain quite forbidding consonant clusters. The Slovak word štvrť, for example, (pronounced /ʃtvr̩tʲ/ and meaning quarter) contains no vowels at all. Germanic languages, too, contain frequent consonant clusters.

Do not be surprised, therefore, if fractions are pronounced with intervening vowels inserted between the consonants (e.g., /sɪəksəθəs/ instead of /sɪksθs/).

In fact, native speakers will often reduce the clusters for ease when speaking rapidly and pronounce sixths as /sɪks/ (eliding the /θs/) so it slightly perverse to insist that learners shouldn't do this.

|

partitive phrases as pre-determiners |

There is a separate guide to partitives and classifiers on this site, linked in the list of related guides at the end so here it is enough to note that many partitive phrases can pre-determine. For example:

- restrictive partitives

- which can only be used with a single or very limited range

of nouns. For example:

I'd like a rasher of that bacon

She broke a pane of the glass

He kept a lock of her hair - typical partitives

- which can only be used with nouns sharing a particular

characteristic (thinness, irregularity, cuboid etc.). For

example:

He put in a slice of the lime

He added a cube of the ice

and a lump of the sugar - general partitives

- which can be used with almost all mass nouns. For

example:

I gave him a piece of my mind

Can a have a bit of the cake?

Give me a chunk of that bread

|

attitudinal pre-determiners: such, what, rather, quite |

It is not the case that all grammarians would include these four words in the category of pre-determiner but, because they share structural characteristics with the other forms discussed above, it is legitimate for teaching purposes to include them. Some analyses will call these intensifying pre-determiners because they serve to amplify or tone down the strength of the noun phrase which follows. What they all do is communicate the speaker / writer's attitude.

- such and rather

- These words have other functions, of course, operating as

adverbials in, e.g., such beautiful work should be

exhibited, rather nasty weather etc.

Here we are concerned with their function as a pre-determiner when they serve to emphasise the speaker's attitude as in, e.g.:

don't be such a baby (= you are being very like a baby)

she is such a nice woman (= she is a very nice woman)

this is such good food (= this is very good food [zero article])

he is rather a stupid player (= more than usually stupid)

they have rather a nice house (= more than usually nice)

The reason many analyses do not include these as a proper pre-determiners is that they can only pre-determine the indefinite or zero article and not the range of possessives and demonstratives etc. which have been exemplified for the real pre-determiners above. We cannot have, therefore:

*such my house

*such those eggs

*such the cat

*rather her car

*rather those apples

etc.

In American English rather is confined to its adverb function but in British English, it is used as a pre-determiner with much the same, although slightly less emphatic, meaning as such. - what

- This word, too, clearly has a number of other uses in the

language but as a pre-determiner it functions to express

surprise, joy or disappointment in exclamations such as:

What an exceptional result!

What gorgeous weather! [zero article]

What a very stupid thing to say!

Again, this word can only pre-determine the indefinite or zero articles. - quite

- This is an anomalous word because it can carry two distinct

attitudinal messages:

1) Positive attitude when used with a non-gradable adjective in the noun phrase:

It was a quite fantastic show

It was a quite disgusting performance

2) Negative attitude when used in other environments:

It was a quite interesting development (i.e., not very interesting)

Sentence stress plays a role here and the stress or lack of it on the pre-determiner can imply a down-toning or intensifying meaning. De-stress the predeterminer and the adjective is emphasised; stress it and the downtoning effect is expressed.

It is also anomalous in that is can occur with the definite article as in, e.g.:

That's quite the best tool for the job

|

notice |

The determiners rather and quite can act as post-determiners,

following the determiner proper so we can have:

It was a rather / quite interesting

development

It was rather / quite an interesting

development

That's rather / quite interesting information (zero

article)

(Arguably, in fact, putting the item after the indefinite or zero

article simply results in its acting as an adverb pre-modifying the

adjective and not a determiner at all.)

We cannot do this with what and such so we cannot have:

*A what beautiful picture

*A such beautiful picture

Summary

|

Pre-, Central and Post-determiners |

So far, the discussion has focused on pre-determiners which modify

determiners proper.

There is, however, an alternative way to analyse somewhat rare

phrases which contain three determiners. In this case, we can

refer to them separately as pre-, central and post-determiners, like

this:

| pre-determiners | central determiners | post-determiners | Examples | |

| multipliers | articles | numerals ordinals |

twice the first

price both my last letters all those first books half her many friends all the six children a third of those 15 groups |

eight times that

last number all my first ideas half those twenty people twice my previous salary both the next films half the second class |

| both, all, half | demonstratives | sequencers | ||

| fractions | possessives | many | ||

The issue to notice, explained in more detail in the guide to

determiners is that pre-determining expressions with the preposition

of function as partitives rather than determiners proper so

we can have, e.g.:

many of her friends

both of the children

a quarter of my salary

all of those six letters

and general partitives conventionally take the first position in the

sequence.

Restricted partitives, because they are determined by the nature of

the noun, often take the place of post-determiners so we may

encounter, e.g.:

both my rashers of bacon

half these loaves of bread

etc. and in these cases, the noun phrase rather than a single noun

is determined.

The distinction between the quantifiers plus of and

generalised partitives proper lies in the fact that the former

cannot be pluralised so while we allow, e.g.:

a bit of information

some pieces of information

a pile of books

four piles of books

and so on, no parallel constructions can be used with the

quantifiers except the fractional ones. We allow, therefore:

three quarters of these apples

five sixths of the first group

but no pluralisation of words like many or several

is permissible. That is not the case in some languages.

|

teaching these forms |

Other languages

Your learners' language(s) will

almost certainly handle these sorts of concepts differently. For

example, it is perfectly OK in Greek to have the my friend

or that the dog. Romance languages, such as Italian

and Spanish, but not French, allow the possessive determiner to

co-occur with the article, too.

In some languages, Romanian, Bulgarian, and Swedish, for example,

affixes (often suffixes) act as determiners.

Other languages, such as Finnish, also have possessive affixes doing

a similar job.

Many of the expressions with the pronoun of acting as partitives of

one kind or another will be realized through the use of genitive

case structures in languages which depend on case marking to express

relationships.

The way to bet is to presume from the outset that pre- and post-determiners will

- be used differently in your learners' language(s) and have different co-occurrence rules

- be virtually untranslatable

- be ordered differently in your learners' first language(s)

- cause problems if they are presented in a piecemeal fashion with no consideration of parallel forms

- cause problems if they are presented all together in an overwhelming mass of data

Contexts

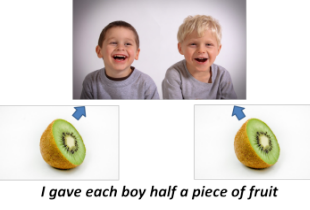

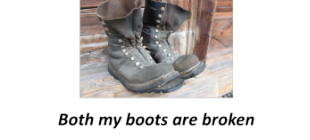

It is very important (not just here) to present these forms in a clear context for which graphics and realia are the obvious source because concepts do not coincide across languages.

For example, it is easy enough to come up with visuals such as:

|

|

|

|

|

How do you feel? It's quite an interesting painting What a beautiful painting What an awful painting It's such a beautiful painting It's rather a boring painting Anything else? Discuss with two other students Find two people who agree with you etc. |

|

At lower levels, especially, a little Total Physical Response

teaching may be appropriate. For example:

John, give all the men a piece of blue

paper.

Mary, give all the students a piece of white paper.

Arthur, give both a green and a white piece of paper to a student

June, give both your pieces of paper to Fred

etc.

Timing

There is almost no point at all in tackling this area at all if the distinction between count and mass noun uses is unclear to your students.

| Related guides | |

| determiners | for more on the forms of determiners in general |

| partitives | a guide to partitives and classifiers |

| adverbs | for more on restrictive or exclusive adverbs |

| adverbials | for more on other forms of verb-phrase modification |

| adverbial intensifiers | for more on this class of intensifying adverbials which serve to emphasise, amplify or tone down meanings |