Functional grammar: an introduction

On this site, most of the language analysis draws on quite

traditional concepts of grammar. This guide, and the guides

related to it and linked at the end are rather different.

A clock is a machine which communicates in a sense: it tells you the

time, as we say: tells.

The ambition of functional grammar is to investigate how it does

that. To look at the ways the various parts work together to

produce the communicative outcome.

This short introduction to functional grammar focuses on the basics of how the grammar classifies items in the language from the point of view of what they do rather than their formal characteristics.

|

An example |

If you imagine a function in language, for example, informing the

hearer / reader of a fact such as:

The puppy was taken to the vet by Mary

it is possible to look at the language formally and state that it is

a sentence in the passive voice which can be analysed as

The puppy (the patient [literally in

this case, although it's the technical term in grammar], made up of a

determiner and a noun)

was taken (the passive verb phrase made up of the

past tense of the verb be and the irregular past participle

of the verb take)

to the vet (a prepositional phrase consisting of the

preposition to and its complement (or object if you prefer)

the vet which has two constituents, the determiner the

and the noun vet).

by Mary (another prepositional phrase which links

the action to the agent)

That is a legitimate formal analysis and, sooner or later, learners

of any language have to come to terms with mastering the systems of

the language in this way.

However, for most learners, the considerable effort of learning

another language has to have more of a payoff than being able to

form a passive clause. Learners want, finally, to be able to

produce accurate and appropriate language which expresses their

thoughts with a good deal of precision. In other words, they

need to know what the communicative effect is of making a passive

sentence and why, for example:

Mary took the puppy to the vet

is not the way the sentence was formed.

A grammarian could tell you exactly how the active voice sentence

can be manipulated to make the sentence passive and it will involve

some quite simple rules concerning the position of the noun phrases

and the form of the verb. In classrooms, a teacher can also

spend time getting learners to convert active to passive voice

clauses and vice versa but that will tell the learners

nothing useful whatsoever about how to communicate in English.

Functional grammar asks a different set of questions. It asks:

- What is the difference in terms of communicative effect on the hearer / reader of stating the fact in the passive or the active voice?

- What effect does putting by Mary at the end of the clause have?

- What made the producer of the sentence choose one form over another?

In other words, functional grammar looks for the reasons for information being organised as it is.

|

Meaning and functions of language

|

Functional grammar has emerged initially from the work of

Halliday in the 1990s and the key distinctions between what are

known as Field, Tenor and Mode. These three aspects make up

what is called the Context of Situation (which is a term that is

rather better defined than what is usually meant by context).

Before we look at meaning, we'll define those very simply:

- Field

- concerns what is being talked about and the goals of the

text.

Is it, for example, intended to tell someone about how snow is formed in the atmosphere or is it a letter to a friend describing a holiday and making suggestions? - Tenor

- concerns the relationship between the speaker / writer and

the hearer / reader.

Is that relationship one of equality or authority? Does the producer of language need to be careful or can they express themselves casually? - Mode

- concerns what type of text is being produced.

Is this a letter, an essay, an email, a telephone message, a face-to-face conversation or what?

Within these three broad categories we can identify three different types of meaning:

- Experiential meaning

- concerns the way we use language to encode our experience of

the world and how we signal the Field of discourse in which the

text is set. For example,

Mary sent a letter to her mother

which simply encodes a fact in language. In this case, it probably represents something known to the speaker personally but it might be the result of hearsay or what Mary has previously said. Experiential meanings can be personal or vicarious.

You probably know, for example, that

The speed of light is nearly 300,000 kilometres per hour

but it unlikely that you have measured it personally. - Interpersonal meaning

- concerns the Tenor of the discourse and how we communicate

with each other to get information, get things done, express our

degrees of certainty and so on. For example

Do you think Mary has sent a letter to her mother?

or

Mary might have sent a letter to her mother

concern in the first a request for a viewpoint and in the second express the speaker's degree of certainty about the event.

In both these cases the tone is quite neutral so it is likely to be a communication to an equal and quite informal. However, if that meaning was encoded as:

I wonder whether you are aware of Mary's ever sending a letter to her mother

the speaker / writer has chosen a different way to encode the meaning to provide some polite distance between the speaker / writer and the hearer / reader. - Textual meaning

- concerns coherence in written and spoken texts and is

closely connected to the Mode of the text in question. For

example, if the response to the first questions is

I guess she might have done

the hearer has to be aware that she stands for Mary and that have done stands for sent a letter to her mother.

In other circumstances, the response might be:

Yes, and I expect she'll be relieved to get it

and the hearer has to realise that she now stands for her mother and forms the subject of what follows (it has, in functional terms, been raised from the rheme of the first sentence to the theme of the next) and it stands for a letter.

In written communication, it is usually safe to assume that there is less shared knowledge between writer and speaker (so things need to be made more explicit) but that there is also pressure on the writer to link information together cohesively to make the relationships clear.

It is of real important to understand that these three forms of meaning are usually expressed simultaneously in the language we produce and that our choices of structure are constrained if not fully determined by the types of meaning we wish to communicate.

If you prefer a diagram this is how the Context of Situation

looks:

The first two kinds of meaning are realised through the systems

of the language:

Semantics: systems of meaning

Lexicogrammar: systems of structure

The Mode is realised through choices of expression: phonology, gesture, graphology.

|

Context of Situation in the classroom |

We may know about Field, Tenor and Mode as defining the shape of

text and its content but our learners often don't, of course.

They will treat any text presented to them or which they are

required to produce, whether written or spoken, on its own terms

without, unless we are explicit, connecting them to the contexts of

situation.

In the guide to reading skills, for example, a text's classroom

purposes are defined in three ways (following Johns and Davies,

1983):

- Text As a Linguistic Object (TALO)

This is use of a text to exemplify grammatical or lexical information, or, if spoken, to exemplify pronunciation features as well. It implies mining the text for information about meaning and form in order to teach language systems - Text As a Vehicle for Information (TAVI)

This use is to train learners to read or listen to a text for information and implication so it is typically a kind of extended comprehension exercise involving listening and reading between the lines as well as understanding the speaker or writer's attitudes and implications. It is, in other words an exercise in pragmatics. - Text As a Springboard for production (TASP)

This is the use of text as a stimulus for productive language practice. This often means providing a model text, written or spoken, which is then analysed for its salient features (using TALO). Then, having delved into the language use, learners are asked to produce parallel language in their freer practice stage of the lesson. It is an approach to language skills teaching suited well to productive skills because the language the learners are asked to produce is based on a real-life model that they have analysed quite carefully.

This often means that, unfortunately, a text becomes a test

rather than an opportunity to see language working in the endeavour

to communicate: inform, ask, entertain, interact, transact and so

on.

There is little wrong with any of these three uses of texts in terms

of methodology but, if we accept that that Context of Situation is a

controlling factor in the production of language, then we need to

give our learners a way to assess what that it.

In other words, learners need explicitly to be made aware of what

the factors are which determine the appropriate way to understand

and produce language.

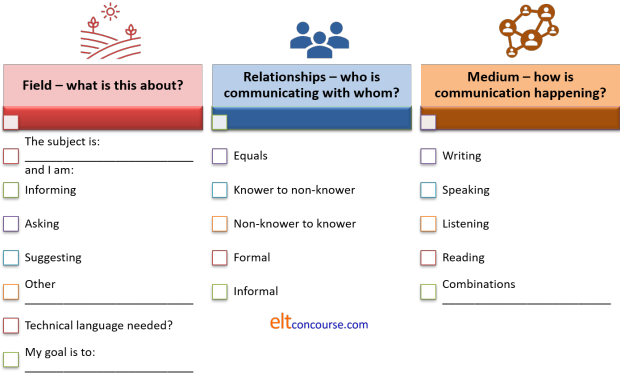

Here's a simple way to make the teaching of skills more embedded in communicative language teaching. It is not necessary to trouble learners with terms such as Field, Tenor and Mode, of course, although they are legitimate bits of language to learn. It is a form of questionnaire for the learners to think about before they are asked to understand or produce a text and looks like this:

A form like this will take about three minutes to complete (and

people get even quicker with practice). If the time is used to

make sure that people know what they are doing, why they are doing

it and with whom, it will be time well spent.

You can, of course, do this as a whole-class exercise (which may be

wise the first time) but it is more effective in raising awareness

if it is done individually or in the pairs or groups that people

will be working in.

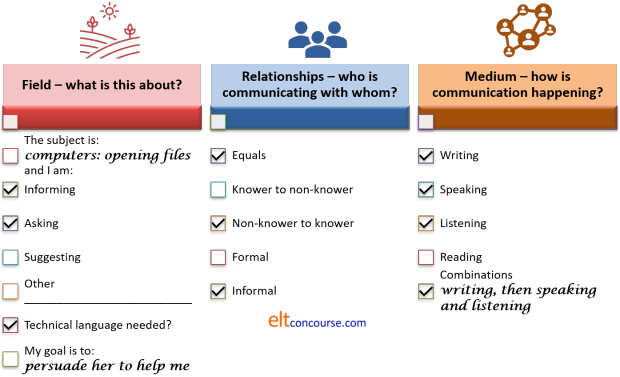

Here's an example of the form filled in for someone completing the following task:

| I am having lots of trouble opening

some kinds of files on my computer because I am working from

home this week. Luckily, a friend of mine works in the IT department of my company so I am writing an email to her to get some advice. I am going to:

|

Now, the learner is alert to the skills needed for the task and

what to do in terms of language functions.

With luck, that will help to get the tone and content of what is

written correct and prepare for a speaking phase to follow.

|

Register and Genre |

These two concepts are often subsumed under the general heading

of text type but that is slightly too loose for our purposes.

The concepts are fundamental to taking a functional grammar approach

to language so we'll define them here:

- Register

- refers to texts which share the same Context of Meaning and are, therefore, describable as occupying the same register. Because they do, they will also exhibit the same (or very similar) experiential, interpersonal and textual meanings. We can, therefore, make predictions about the lexicogrammar of such texts because, whether they are in the register of teacher-student talk, economic papers, political interviews or whatever, they will have meanings in common.

- Genre

- is a cultural concept. When texts share the same purpose,

they will often share the same structural elements and they

therefore can be said to belong to the same genre.

The ones most often identified are: Recount (saying what happened), Narrative (telling a story), Procedure (saying how to do something), Information report (presenting information), Exposition (arguing a case) and Discussion (looking at both sides of an issue).

So far, we have introduced some basic concepts of a functional

approach to analysing text. What we need to do now is

investigate how best we can describe language. Like every

other speciality, functional grammar and a functional approach to

language description requires its own metalanguage, i.e., the

language we use to describe the language we use.

What follows is an attempt to identify the most important concepts.

It is important at this stage to note that functional grammar does

not dismiss the language of more traditional grammars or attempt to

replace the concepts with something wholly new. It is better

to consider functional grammar as drawing on and extending more

traditional concepts.

Functional grammar is not a replacement for what has been called,

rather loosely here, traditional grammar. Fundamental concepts

such as lexeme, word classes, subjects, verbs, objects, clauses and

sentences and so on are common to both kinds of grammar.

Nor are the grammars mutually exclusive because many concerns of

functional grammar are identical to those of more traditional

grammars. In fact, it is often difficult to see whether an

analysis is being conducted from a functional viewpoint or a formal

one because it is inevitable that considerations of meaning and

intention will arise whatever grammatical or structural form it is

that one is attempting to analyse.

What is different is the focus and with that focus comes the need

for a different way of looking at things and, often, a different set

of terms to apply to concepts.

|

Rank ordering |

Traditional structural linguistics conceived of a hierarchy of

structural items and functional grammar is, in this respect, no

different. The terms differ somewhat but the analytical import

remains.

In functional grammar, the following ranks are identified:

- Morpheme:

This is the smallest meaningful unit of language. For example, we can see that anti in antibiotic and mis in misunderstand carry some sort of meaning (against and wrongly respectively).

Words, the next in rank order can consist of a single morpheme such as

take, joy, people, happy, then, at, he etc.

or they may be formed of more than one morpheme such as:

taking, joyful, peopled, happiness, delimit, himself etc. - Word:

A word consists of one or more morphemes.

For clarity's sake, traditional grammars distinguish between a word, which, in English, may be defined as a meaningful unit of language with a space at each end, and a lexeme which may consist of more than one word but represent a single concept. All the following are lexemes but only two are individual words:

have, entitlement, bring up, The White House, thunder and lightning, the bee's knees etc. - Group or phrase:

A group or phrase consists of one or more words.

The term group is used in functional grammar to represent what can be conceived of as an extended word. For example:

just as we can have:

in which each word has a functional role, we can also have:Vets treat animals Subject Verb Object

and the grammatical functions remain the same.The nice vet with a surgery in the village will treat abandoned animals Subject noun group Verb group Object group

The term phrase in functional grammar is confined to the prepositional phrase which is analysed more like a mini-clause than a group because prepositional phrases consist of the preposition itself and a noun group acting as its object (often, in other grammars, called a prepositional complement). For example:

a traditional analysis would be:

but a functional analysis would usually be:The nice vet will treat abandoned animals in spite of the fact that he gets no money Subject Verb Object Preposition Prepositional complement

This may not seem a particular important distinction to make but it has implications in terms of focus.The nice vet will treat abandoned animals in spite of the fact that he gets no money Subject Verb Object Preposition Noun group prepositional object

Functional grammar recognises only the following groups or phrases:- a noun or nominal group:

the old man in the boat

he

the picture

etc. - a verb or verbal group:

eats

can have

should have come to help

might go - adverbial group:

then

very carefully

extremely rapidly

scarcely at all - conjunction group:

and then

before

and

so that

but ... also - preposition group:

in front of

by

directly between

all along - prepositional phrase (a preposition plus its object):

over the water

including the tax

behind the curtain

- a noun or nominal group:

- Clause:

A clause consists of one or more groups or phrases.

These consist of one or more groups or phrases and contain verbs of one kind or another. In some traditional grammars, a clause is defined as a group containing a finite form only. So, by that definition, the following are clauses:

The old man rowed the boat

My passport was stolen

I wanted a biscuit

all of which contain more than one group and a finite verb so can be analysed like this:

In common with most other modern grammars, however, functional grammar also recognises non-finite clauses. Examples of non-finite clauses are:Noun group Verb group Noun group The old man rowed the boat My passport was stolen I wanted a biscuit - On opening the box, I discovered that the vase was damaged

- What you need to do is press on the blue button there

- Written on the box was his return address

- To send the parcel like that was silly

- Clause complex

A clause complex consists of one or more clauses.

This is what is often referred to as a sentence and consists of one or more clauses. All the following are clause complexes:

My mother is at home

John is not at home but I can call him if you like

Although Peter was happy to meet me, his mother was sick at the time so he couldn't get away from the house and we met at his place.

It is, of course, possible for clauses complexes to work together to make longer texts but that kind of analysis belongs in the description or rhetorical analysis rather than grammatical analysis.

|

Subjects and finites |

Another distinction that is crucial in functional grammar is to

recognise subjects and finites.

Subjects are usually fairly easy to recognise because they are

typically (i.e., not invariably) nouns or noun groups so, for

example, in

The old man in the boat would wave to us

it is straightforward enough to recognise that the noun group, The old man in

the boat is the subject of the verb group would wave.

Just as in most other grammars, however, a subject can also be

- a nominalised wh-clause as in:

How the old man waved appeared friendly - a verb + -ing (usually abbreviated as Ving):

Waving at us was friendly - a that-clause:

That he was waving at us showed he was friendly - an infinitive with to (usually abbreviated to

to + V):

To wave at us was friendly of him

Finites are a less intuitive constituent of clauses but in that

sentence, the finite is the word would. Finites are

always the first item in a verb group.

Finites can sometimes be identified quite easily by three rules:

- Finites are always the first item in a verb group

She has been explaining the problem - Only finites are marked for tense

They listened carefully - Only finites are marked for number

She appears happy

The problem with identifying finites in English particularly is

that rules 2. and 3. are not always safe to apply. For example

in:

I cut the wood

the tense could be past or present and the form of cut

would also be unchanged if the subject were they, you or

we although it would change, in the present only, if the

subject were he, she or it.

Modal auxiliary verbs also function as finites and their forms do

not inflect at all, although they are invariably the first item in a

verb group.

In common with most other types of grammar, functional grammar also recognises non-finite clauses, although some very traditional grammars :

|

Other focusesObjects |

If we take a sentence such as:

The kind vet will often treat abandoned animals without a

fee

we can recognise other important constituents of clauses:

- The object noun group

In this case, it is the group abandoned animals and we saw at the outset that the group can be raised to the subject position if we make the sentence passive. - The adjunct phrase

In this case, it is the prepositional phrase without a fee. Adjuncts modify how we see the verb. Adjuncts are realised usually by prepositional phrases or adverbs and in this case we have another adverb adjunct, often, modifying how we see the verb group.. - The predicator

In this case, it is the verb treat. The predicator is everything in the verb group except the finite and, as we saw, the finite in this verb group is will. - Describers

These come in two sorts:- kind is an epithet which modifies the noun group vet. Epithets can themselves be modified by adverbs so we could have the very kind vet.

- abandoned is also a form of describer but in

this case it has two important characteristics.

- It is a classifier rather than a describer because it tells us what sort of animals we are dealing with. We cannot, for example, modify the word with very to produce *very abandoned

- Secondly, it is formed from the verb abandon

so it is a participle classifier.

There are two types of these, too, which cause problems

for learners. Some are formed with verb + -ing

and some from verb + -ed so we could have:

The practising vet treats the abandoned animals

Finally, if we take a different sentence as our example, such as:

The vet is kind

we can see that the word kind cannot be the object of the

verb is because no passive equivalent can be formed.

It is called the complement and linking or copular

verbs such as be, seem, appear, taste, smell, become and so

on are conventionally followed by complements rather than objects.

Complements are not only adjective groups in functional grammar

and can be object noun groups (example 1. above), nominal clauses as

in, e.g.:

I wanted to see the

animals

and prepositional phrases as in, e.g.:

His office is on

the fourth floor

|

Implications for learners and learning |

One of the problems with using a traditional grammar in

classrooms is the tendency it has to confuse function with class

labels. For example, if we characterise the normal word

ordering in English as Subject - Verb - Object we are mixing up the

categories.

The word Verb is a word-class descriptor but the terms

Subject and Object are functional descriptors telling

us what things do in terms of making meaning.

We can, of course take the usual definition of verb as a word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence and that is adequate as far as it goes but is a description of word class, not function. Functionally, verbs perform different purposes:

- doing:

Vets treat animals - being:

She is a vet - saying

I spoke to the vet - thinking

The vet believed it was curable - feeling

The vet loves animals

Traditional grammars also contain a word class called adjectives but we saw above that there is a critical distinction between describers and classifiers which is not captured by the simple term adjective.

Recognising that words have functions and class is a first step

in recognising that how we teach grammar must take into account

meaning as well as the formal characteristics of items in the

language.

This does not mean abandoning tradition concepts but it does mean

refining them in terms of meaning.

Many languages, especially non-European ones, do not distinguish so readily between finite and non-finite forms. At beginner level, especially, this can lead to many problems because recognising the finite in a clause leads to being able to inflect it appropriately and recognise tense forms, number and person and more. Failure to recognise the subject and the finite can lead to errors such as:

- *Often we eating with my family at weekends

- *He can goes to the cinema with you

and so on.

This was the introduction. For more, try:

| Related guides | |

| experiential meanings | a short overview of an important area of meaning |

| verbal processes | for more detail |

| circumstances | for a guide to this important area of experiential meaning |

| genre | for some consideration of how particular forms of circumstances will appear in text types |

References:

Butt, D, Fahey, R, Feez, S, Spinks, S and Yallop, C, 2001, Using Functional

Grammar: an explorer's guide. Sydney: NCELTR

Halliday, M, 1994, An introduction to functional grammar: 2nd

edition. London: Edward Arnold

Johns, T. and Davies, F., 1983, Text as a

vehicle for information: the classroom use of written texts in teaching

reading in a foreign language, Reading in a Foreign Language 1/1:1-19.

Lock, G, 1996, Functional English Grammar: An introduction for

second language teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press