Teaching the article system

Before tackling this guide, you should have worked through the

language analysis guide to

the article system and satisfied yourself that you understand how it works in English. If you want to try the test to refresh

your memory

you can click

here. The test will open in a new tab so

just

shut it to return.

|

Other languages |

It's quite common to hear people say this or that language doesn't

have articles and it's sometimes true but the real situation is

a bit more complicated. It is true that it is easier to list

common languages which actually do have an article system

similar to English because there are so many that have nothing of

the sort. Most common

languages do not have an article system anything like English, in

fact.

Here's a brief run-down of some major languages and language groups.

| Languages with no obvious article system |

|

This is a long list and

includes: All Slavonic languages (with the exception of Bulgarian and some other southern Slavic languages), Chinese languages, Japanese and Korean, Turkish (and other Turkic languages), Thai and other South-East Asian languages and some other European languages such as Finnish and Basque. Note: Some of these languages do have a way to express what is called the partitive (some). Finnish has a whole grammatical case for it (and 14 other cases). In Russian and some other Slavonic languages it can be rendered by pluralising one and in Japanese the demonstrative sono can be used this way. |

|

Implications Speakers of these languages will have huge trouble. They will almost randomly leave out articles when they are needed or insert them when they are not, even at advanced levels because they have few conceptual hooks to hang things on. We can expect errors, therefore, such as: *She is very nice teacher *What the films do you like? *She was in a pain and so on. The concepts of definiteness and indefiniteness, let alone countability and uncountability are sources of deep and abiding conceptual confusion. |

| Languages with an article system akin to English |

| This list is mostly confined to

European languages and includes: Greek, Hungarian, the Romance languages (Spanish, Italian, French, Romanian etc.), Scandinavian languages and Germanic languages (German, Dutch, Afrikaans, English etc.). Some European languages such as South Slavic languages like Albanian have an article system based on affixation, using suffixes for the definite article only. Basque is similar in this respect. Some languages, such as Swedish, Norwegian and Danish have either a suffix or a separate definite article depending on their position in a sentences. Some languages, notably in India, have an indefinite article but use suffixation to note definiteness. Note: Although all these languages have some kind of article system, how articles are deployed is very variable. Greek, for example, uses an article before proper names (the Maria etc.) and omits them in subject complements (She is teacher). Like Italian and a number of Romance languages, it also uses the definite article where English would not (The tigers are dangerous animals, the money is important, I was on holiday in the France etc.) Spanish, unlike French and Italian (but similar to German) can use the definite article as a pronoun: my book and the of John. |

|

Implications Errors will occur frequently because of analogy with first languages but they will not be random. Conceptually, there are similarities. Most errors are traceable to the learners' first languages and alerting them to differences in use will be productive. Expect errors as in the examples above. |

| Arabic, and other

Semitic languages are something of special case. Arabic has both a definite and indefinite article system. Indefiniteness is signalled by the addition of a suffix (un), a process called 'nunation'. The definite for all genders and numbers is the prefix al- / el-. (The 'l' may be assimilated to a following letter.) Although the concept of indefiniteness is known, the uses of the indefinite article in English cause great difficulties. Usually, Arabic speakers simply omit it: *He is teacher. |

It should be clear from the above that this is an area which has to be approached very carefully and systematically. It is unlikely that speakers of languages which don't have an article system will simply acquire the system by exposure to it. They'll need a rule or two to help especially when they are writing and have time to consider how to apply them.

|

Keep it simple |

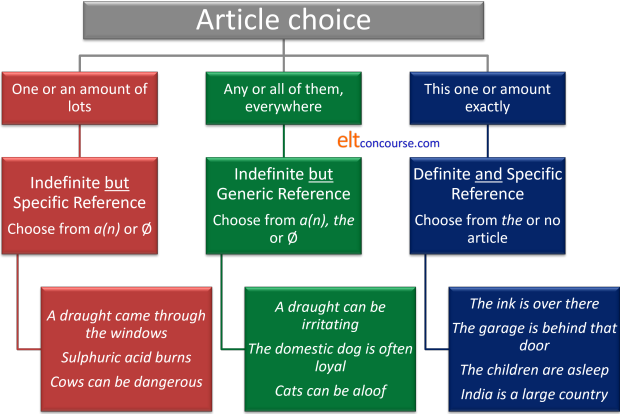

If you have worked through the guide to the article system, you'll know that it's really quite complex. Bear in mind that the rules in that guide where there to help you understand the system, not your learners. Here's the overview to remind you:

So, here's a suggested sequence of rules for

students which, while simplifying the area (and running a risk of

inaccuracy), will help in many situations. Learners can refine

their production later to deal with exceptions and oddities.

None of the following teaching ideas involves the use of a gap-fill

or text-completion task. Such things are useful in their place

but there's a cautionary note at the end.

Can you make the first rule from these examples? Click here when you think you have it.

- A man parked a huge van outside my house and the thing stayed there for weeks. Eventually, the man came and took the van away.

- When you go out, would you get me

some cigarettes

and a paper?

(Some hours later)

Hi, here are the cigarettes but I forgot the paper.

The

essential

first rule is the known / unknown rule: Unknown nouns

get the indefinite article when they are first introduced and

the definite article thereafter. (For the purposes

of teaching, we can describe some as the plural indefinite

article, even though it isn't.)

This rule works over long periods of time and across

lots of intervening text. It's also quite easy to remember

the known / unknown distinction. Teaching the rule and

practising it are quite simple, too.

Here are a couple of ideas:

-

Go round the class making up a silly story. Everyone has to make a comment about the 1st object introduced and then introduce a new one. Like this:

A: A cat came into my room.

B: The cat brought a mouse with it.

C: The mouse was still alive so I took it away and put it in a box.

D: I put the box in the corner where the cat can't reach it and gave the mouse some food.

E: The mouse didn't eat the food so ...

and so on. This can be done orally or in writing and developed to include writing a story or telling an anecdote. Make sure all the language surrounding the article use is simple for the learners. They have enough to think about. -

Get people to look out of the window and explain to others what they can see. The others then have to ask questions. Like this:

A: I can see a woman in a coat.

Q: How old is the woman? Q: What colour is the coat?

B: I can see some policemen and a boy.

Q: What are the policemen doing? Are the policemen talking to the boy?

etc. etc.

OK. Now see if you can make the second rule from these examples. Click here when you have it.

- A: Who's he?

B: He's the teacher. - A: What's her job?

B: She's a teacher. - A bank was robbed yesterday but the criminal was caught.

- I want to have lunch with the President (of the United States).

This rule is the so-called the rule of uniqueness or

classification.

Uniqueness can be intrinsic (the President) or

by association

(the criminal). In both cases we are dealing with something we

know there is only one of.

In dialogue 1, we are alerted by the use of the definite article

that the speaker is saying that he is the teacher of this class,

i.e., the teacher has been classified and is unique in some way.

In dialogue 2, the use of the indefinite article signals that

she is one example of a group. We can classify her further by

using the definite article and saying something like, She's

the

history teacher. Note, however, that this implies a special

history teacher because there are lots of them so we could say

She's a history teacher just as easily, with a different

implication.

In sentence 3, we know that we are referring to the criminal who

robbed the bank, not to any old criminal. If we said, ... and

a

suspect was arrested, we instantly grasp that there were a

number of suspects, not just one.

In sentence 4, we all know there is only one President:

the role

is unique and doesn't usually need further classification if

both speaker and hearer share a cultural milieu. If they don't,

we may need to add the ... of ... classifier.

Teaching the rule and practising it are quite simple, too.

Here are a couple of ideas:

-

Gather up some pictures of famous people and distribute them. Without naming the person, learners have to give each other clues to guess the person such as:

He's the actor who starred in ....

He's the fifty- first president of the United States

She's the leader of ...

This practises the rule of uniqueness through classification and it needn't be done with relative clauses. -

Extend the rule of known / unknown in the story-telling format with learners extending the story in turns. Something like:

A car parked outside a house last night and the driver went to the door. The people in the house came to the door and the man gave them a letter in an envelope. The name on the envelope was ...

The second of these exercises meshes seamlessly with reinforcing the first known / unknown rule.

Finally, see if you can divine the last rule from this example. Click here when you have it.

Dogs shouldn't eat sweets, I know, but I gave the dog some sweets because I know he likes sugary things.

This

is the

real object vs. general idea rule. When

we are speaking in general about something we don't use the

article; when we are talking about something real, here and

now, we do. If it's countable, use the plural, if not,

use the singular.

At the beginning of the utterance, the speaker is referring

to dogs in general and sweets in general but goes on to talk

about a particular, real dog and some particular,

real sweets. At the end, the speaker

is talking about sugary things in general.

So we can say things like, I like chocolate (meaning

in a general sort of way) and I liked the chocolate

(referring to something I actually ate).

Here are a couple of teaching ideas:

-

Present the class with some contrasting statements such as:

She likes biscuits but not the biscuits I bake.

She loves sweet things and ate all the cakes.

and get them to work out the distinctions.

Then get them to complete the sentences

She likes science fiction movies so ... [she bought the DVD of ...]

I enjoy reading so I took ... [the / some books with me]

etc. -

Get students to work out the difference in meanings.

I like books.

I liked the book.

I like pasta.

I enjoyed the pasta

and so on. -

Get the students to write a list of things they like and don't like, enjoy and don't enjoy and then get them to talk / write about the consequences of their preferences.

E.g., I like beaches and water so I chose a resort near the beach and swam in the beautiful clear water every morning.

(The ideas for the third rule do not cover the unusual (and more formal) use of a singular noun to represent a general idea (The tiger is a dangerous animal). This is essentially the same as generic reference without the article, using the plural for countable nouns (Tigers are dangerous). The singular use is very much rarer and can always be replaced by the first type so it can safely be left to higher levels when the learners can already handle the three basic rules.)

|

Gap-fills and missing article texts |

Traditionally article practice is an area where filling in gaps with the, a, an or Ø is a popular classroom or study technique. A word of caution: while these techniques are sometimes useful, there are two problems:

- The exercises tend to test rather than teach so need to be used after you have done some teaching of the system.

- Just removing all the articles from a random text will result in an unfocused exercise in which a variety of article rule use will need to be applied. Consider this text:

Brighton is largest seaside resort in south-east of England. For many people it seems town of contrasts, mixture of elegant eighteenth-century architecture and loud modern places of entertainment. Town was at first fishing village and did not become popular until eighteenth century, when doctors began to prescribe sea-bathing as cure for illnesses. Rich people began to visit Brighton in large numbers, and when Prince of Wales, later George IV, arrived and decided to build house there, its future as tourist centre was assured.

Successfully to insert articles only where they are needed in that text requires the application of all of the above rules, and some. It is a very challenging and potentially confusing task, even if you make it easier by signalling where the articles should be put. It is usually wiser, therefore, to construct gap-fill or completion-task texts which focus the learners on only one rule (or at most two) at a time. It's not difficult to do.

If you have students who would like a visual breakdown of the system (or you would like it), right-click and copy this. Don't forget to reference it, please!

| Related guides | |

| the article system | for an overview of the analysis |

| determiners | for the guide to other determiners in English |

| pre- and post-determiners | for the guide to these related forms |

| partitives and classifiers | for more on how the uncountable is made countable |

References:

Campbell, GL, 1995, Concise Compendium of the World's Languages,

London: Routledge

Swan, M and Smith, B (Eds.), 2001, Learner English, 2nd Edition,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press