Catenative verbs: gerunds and infinitives etc.

The verb catenate (which has its origins in the Latin

catena, a chain) may be defined as join together in a

series.

You may be familiar with the term catenation as it is used in

the analysis of connected speech where it refers to how sounds are

linked. That is not the concern here but the concepts are

analogous.

There is a range of verbs in English which can be followed by a

non-finite form in a chain of meanings.

That non-finite may be the to-infinitive or

the -ing form. A few verbs also catenate with the

bare infinitive.

Here's an example of a catenated structure:

I agreed to try making more effort

in which the main, finite verb is agree and its complement

consists of a clause with two non-finite verb forms:

to try, making.

How verbs catenate and the associated grammar are a source of

considerable error for learners of English for two reasons:

- It is not easy to predict which non-finite structures will follow a verb.

- Other languages do things differently and not all have anything similar to the English non-finite forms. Even those that do will not usually have a choice of forms to pick from.

(If you are wondering, the verb is pronounced /ˈkæ.tɪ.neɪt/, the adjective is /ˈkæ.ˌtɪ.nət.ɪv/ or /kəˈti:.nə.tɪv/ (your choice) and the noun is pronounced /ˌkæ.tɪ.ˈneɪ.ʃən/.)

This area is closely connected to the concept of colligation.

Verbs which catenate in the same way such as, for example:

She determined to work hard

They chose to work hard

We decided to work hard

are said to form colligates insofar as they are primed (Hoey 2003)

to take on certain syntactical structures, in this case, the verbs

determine, choose and decide are followed by the

to-infinitive.

The whole of what follows is an effort to identify colligates: words

which function syntactically in the same ways.

If you are here for a particular issue, you may

find this menu helpful. If not, simply work your way through.

At any time, clicking on -top- will return you to this menu.

|

What catenative verbs are not |

Unfortunately, there is a good deal of confusion concerning what qualifies as a catenative structure. There are websites, unnamed here, the authors of which assume that any clause which contains more than one verb is an example of catenation. That's unhelpful because it is careless, sloppy and vague and leads to poor classroom focus.

Before we consider what sorts of structures are involved, we need to make clear what are not, sensu stricto, catenative verbs.

None of the following is an example of catenative verb use for the reasons given:

- She arrived running

because the participle, running, is just a description of how she arrived. It is adjectival, in fact and akin to, e.g.:

The running woman. - He stopped to check the time

in which the main verb is followed by what looks like a to- infinitive. It is not. The nature of to in that sentence is a reduced form of the quasi- or marginal subordinator in order to which is replaceable by with the intention of or a subordinate clause such as so that he could, so as (not) to etc. This is sometimes called the infinitive of purpose although it is not an infinitive, it just looks like one. - He went to work

in which the word to is a preposition of place followed by the noun. It may, alternatively, mean that he went in order to work but that still is not an example of catenation because it is the same as the last point. - She waited before speaking

in which we simply have a verb followed by a prepositional phrase adverbial. The form of the verb when it is the complement (or object) of a preposition is generally the -ing form because it is acting as a noun.

However, in:

She waited to speak

we have a case of true catenation. - I allowed him to leave

because the indirect object has been inserted, thus breaking the chain. In the passive, this verb does catenate as in, for example

I was allowed to leave.

For teaching purposes, this technical point concerning the insertion of the object breaking the chain can usually be ignored (but see below for awareness raising of the basic structure).

There is a range of verbs, almost all of which are to do with suasion of some kind which take a direct nominalised clause with the to-infinitive as the object.

The structure they conform to is:

It is probably impossible to come up with a complete list but this is near enough:Structure: subject verb indirect object nominalised clause as direct object Examples: She persuaded her mother to lend her the money Peter and John forced their elder sister to sell her house

* This verb is only used with a negative clause as its object.advise

ask

beg

beseech

coach

coerce

commandcompel

convince

counsel

direct

drive

employ

encourageenjoin

exhort

expect

forbid

force

goad

hireimplore

incite

induce

instruct

invite

order

paypersuade

press

pressur(is)e

prompt

provoke

push

remindrequire

summon

teach

tell

train

urge

*warn

As we saw, none of these verbs is properly catenative in the active voice but all may be seen that way in the passive. We get, therefore:

She was compelled to leave

I was persuaded to come

They were paid to go

and so on.

For our purposes, these are analysed as verbs taking nominalised to-infinitive clauses as their objects rather than as catenative verbs per se.

Another issue is that modal auxiliary verbs, which

are often followed by the bare infinitive non-finite form or even

the to-infinitive are not

usually considered examples of catenation. So, for example:

I must go now

She should arrive soon

I have to start somewhere

etc. are not considered here.

However, there is a grey area when we come to consider semi-modal

auxiliary verbs such as dare, need and used.

When these verbs are used as full modal auxiliaries as in, for example:

I dared not ask again

I need not tell you

Used he to work here?

they are not considered examples of catenation but when they are

used as full lexical or main verbs in, for example:

I didn't dare to ask

I don't need to do that

Did he used to work here?

they may be considered examples of catenation but will not be

included here as the marginal modal auxiliary verbs are dealt with elsewhere on this site

(linked below in the list of related guides at the end).

Finally, we need to consider prepositional verbs and phrasal-prepositional verbs, some of which catenate as in, for example:

She went on talking

I put off meeting him

Her time was taken up with caring for her children

All these are examples of catenating multi-word verbs but, because

adverb particles and prepositions are always following by the -ing

form, they will not intrude on the following analysis.

|

Six issues |

The problem facing learners (and teachers who are concerned not to confuse learners) is that there are six possibilities to consider in terms of what verb form may follow the main verb in a clause. Here they are with examples of each and each will be considered in a section in this guide.

- Verbs followed by the non-finite to-infinitive. For

example:

She hoped to help - Verbs followed by the non-finite -ing form (also called a

gerund). For example:

She avoided meeting me - Verbs followed by to plus the -ing form.

For example:

They looked forward to staying at the house - Verbs followed by the bare infinitive. For example:

She helped make the proposal - Verbs followed by either the to-infinitive or the -ing

form with no change in meaning. For example:

They started to work

They started working - Verbs followed by either the to-infinitive or the -ing

form but with a change in meaning. For example:

I regret to say that he can't be here

I regret saying that he can't be here

Nearly all verbs which naturally catenate fall into one of the

first two categories so they are the ones which should receive the

most focus, especially at early stages of learning.

We can include the verbs in point 5. at any stage because it really

doesn't matter which form the learner selects.

(One important verb is alleged to catenate with the past

participle form as in:

We got lost

she got sacked

Mary got investigated

but a better analysis of this construction is the use of

get as a dynamic passive, so you will see no more of it here.)

The following contains some long lists. If you want them as a PDF document, there is a link at the end.

|

Do we call it a gerund, a verbal noun, a deverbal noun or an -ing form? |

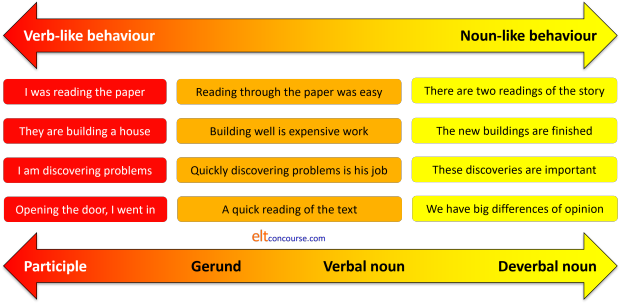

A difficulty we shall encounter here is the function of the verb. In some analyses, people prefer to use the term -ing form to describe the catenating verb in many of the examples below. In others, the term gerund is freely used. In others, a distinction is made between a verbal noun, a deverbal noun and a gerund (although the borderlines are somewhat fuzzy).

Technically, both a gerund and a verbal noun may be defined as

a verb form which functions as a noun, but that is slightly

misleading because there is a cline between the use of a

word as a verb and its use as a noun derived from the verb so, for

example:

He is flying to Scotland tomorrow

is clearly the use of flying as a verb.

and in:

Is flying cheaper?

the use of flying is much more like a noun because it can be

modified by the adjective cheaper. It cannot,

however, be preceded by an adjective or made plural as most nouns

can. It is also rare to see it modified by a determiner so

both:

the flying

and

the excellent flying

are vanishingly rare and

*her flyings

is plain wrong.

In these examples, the -ing form is a verbal noun rather

than a gerund because gerunds may be modified by adverbs and the

form flying cannot be modified that way. We cannot,

for example, use:

*cheaply flying

as a modified noun phrase.

However, in:

The beautiful furnishings in the house

the word furnishings is clearly a noun because it is modified by the

definite article and the adjective beautiful as well as being made

plural in the normal way. It is, nevertheless, also derived by

adding the suffix -ing to the verb furnish.

In this case we are dealing with a noun derived from a verb which is

fully noun-like in all regards so it is a deverbal noun.

Almost any verb can be used with the -ing form in some way.

The question is to see whether the word is acting more as a verb or

more as a noun. It is not always an easy choice.

So, the difference between a gerund, a verbal noun and a deverbal noun lies in the fact that gerunds retain verb-like qualities partially lost in a verbal noun and lost altogether in deverbal nouns. Like this:

- Gerunds retain verbal characteristics even when they are

acting as pseudo-nouns so:

- They may be used with possessive determiners so we

allow:

My confessing the truth solved the matter - They can take direct objects so we can have, e.g.:

John's telling her was a mistake

where her acts as the direct object of the gerund. - They are modified by adverbs just a true verbs are so we

can have, e.g.:

Driving quickly was dangerous

in which the gerund is modified by the adverb quickly and we cannot have:

*Quick driving was dangerous - Gerunds form at best uncountable pseudo-nouns and are

not pluralised so we cannot have:

*His frequent drivings to London - Gerunds are only formed by the addition of the -ing suffix. For this reason, deciding is classifiable as a gerund but decision cannot be. Both are, however, nouns clearly derived from the verb.

- They may be used with possessive determiners so we

allow:

- Verbal nouns occupy a midway position taking on many of the

characteristics of gerunds plus some more noun-like qualities.

- They are noun-like insofar as they can form the subject

or object of a verb, just like gerunds so we get:

Swimming is enjoyable

I dislike waiting - They may be modified by adjectives rather than adverbs

as in:

Slower driving is usually safer - They do not take direct objects so we do not allow:

*His building the house took time - They are uncountable mass concepts and cannot be

pluralised so we do not allow:

*His many drivings to London

- They are noun-like insofar as they can form the subject

or object of a verb, just like gerunds so we get:

- Deverbal nouns act as nouns in all respects and they often

carry the sense of the verb's completion, so:

- They cannot take a direct object because they are not

verbs so we do not allow:

*His painting the village looked awful

and need to insert a prepositional phrase to get the same meaning as in:

His painting of the village looked awful - They are modified by adjectives, not adverbs so, e.g.:

I did some necessary washing

in which the -ing form may not be modified adverbially so:

*I did some slowly washing

is not allowed. - They can form countable nouns and can, therefore,

be pluralised in the normal way of nouns as in, e.g.:

The fittings in the house were expensive - Deverbal nouns may be formed in other ways from verbs and

not only with the -ing suffix so we can have, e.g.:

discovery as a noun from the verb discover

finish as a noun from the verb finish with no changes (a process of simple conversion)

carriage as a noun from the verb carry

refusal as a noun from the verb refuse

and so on (for more examples of how nouns are formed from verbs, see the guide to nouns, linked below). All the resulting nouns are fully noun-like in behaviour and carry little verbal force.

- They cannot take a direct object because they are not

verbs so we do not allow:

Here's a handy, cut-out-and-keep summary of noun-like verbs:

It is not always as simple as this suggests because there is a cline from purely verbal uses of a word to purely nominal uses via gerunds which have characteristics of both verbs and nouns up to verbal and deverbal nouns. We can summarise this cline like this:

This issue will soon become apparent when we consider the

difference between, for example:

I was not permitted to smoke in the room by

the hotel

and

The hotel did not permit smoking in the room

In the first case, we have a catenative structure with permit

followed by the infinitive with to and that is analogous

to, for example:

The hotel did not permit me to smoke in the

room

In the second case, the form is analogous to:

The hotel did not permit pets in the room

and that is evidence that we are dealing with a verb,

permit, and its direct-object noun, pets. If

pets is clearly a noun then, by analogy, we should also consider

smoking a noun in the same environment. But pets

is a plural and there is no plural of smoking.

Another noun-like quality of -ing forms is their ability

to act as classifiers, a grammatical role usually considered the

domain of nouns. For example, just as we can have

a pet passport

we can also have

a flying lesson

a smoking area

the furnishing department

and so on.

The upshot of all this is that it is not always enough simply to

state that such and such a verb is followed by the gerund or an

infinitive. We have to make a decision about whether the -ing

form is really a verb or actually a verbal or deverbal noun derived from a verb acting

as the subject or object of another verb.

Two more examples will help to show the difference.

- In:

I hope to fly early tomorrow

we have a case of verb catenation with the verbs hope and fly linked together. So, therefore:

*I hope flying early tomorrow

is malformed and unacceptable.

However, in:

I hope flying will not be too expensive

we have a verbal noun acting as the object of the verb hope and that is not a case of catenation. - In:

He decided to race on Sunday

we have catenation again, with the verbs decide and to race following each other directly. So, therefore:

*He decided racing on Sunday

is not acceptable because decide is a prospective verb which takes, as is conventional, the infinitive with to.

However, in:

I watched the exciting racing

we do not have a case of catenation because racing is clearly a noun (albeit a verbal noun) preceded by the definite article and an adjective which also break the chain. It is, however, not fully noun-like because it cannot be preceded by the indefinite article or made plural, so both

*a racing

and

*the racings

are not allowed.

It does have other noun-like characteristics, on the other hand, because it can be classified by a noun and it can be modified by an adjective as in, e.g.:

I watched the horse racing

The motor racing was exciting

The exciting formula one motor racing is what I watched

etc.

For this reason, we distinguish below between a noun formed from a

verb and a verb with the -ing ending. The

term gerund will be confined to those

examples in which the insertion of a noun is possible without a

change in meaning of the verb so, for example:

I hate swimming

and

Swimming is enjoyable

both contain gerunds and can be replaced with other nouns not

derived from verbs so we can also have:

I hate fish

and

Fish tastes awful

by analogy.

In other cases, the use of the term -ing form will usually be preferred.

|

Verbs followed by the to-infinitive |

| agree to cooperate |

In nearly all cases, the use of the to-infinitive

signals that the event represented by the main verb takes place before that

represented by the following verb(s).

In other words, the use is prospective rather than retrospective.

This is not an absolute rule but is certainly the way to bet.

For example, if one says:

I agreed to come

then the agreeing clearly precedes the coming.

This rule of thumb applies even when the following action is

unfulfilled as in, e.g.:

I declined to go with them

because even here, the declining precedes the not going.

Incidentally, the prospective nature of the to-infinitive

also explains the use and meaning of the going to structure

(so called).

Coursebooks and many teachers (and many teacher trainers) are wedded

to the idea that going to is some kind of mysterious

structure confined to future intentionality.

It isn't, naturally, because it is simply the verb go

followed by a to-infinitive in the same way that verbs such

as want, hope, expect, plan, aim, intend, mean and many

more are used.

They all denote a prospective aspect in some way and are all

analysable in precisely the same way.

In other words, the structure is not:

going to + the bare infinitive

it is:

going + the to-infinitive.

The upshot is that:

I'm hoping to go

I'm intending to go

I'm meaning to go

I'm going to go

are all more or less synonymous barring the strength of the

intention signalled by the verb. That consideration is

semantic not grammatical.

|

Difficulties with the to-infinitive |

| stop to check the map |

There are three issues to consider:

- The first issue with the use of a to-infinitive

after a verb is distinguishing it from the so-called infinitive

of purpose, i.e., the to which forms part of a

complex marginal subordinator (in order to) linking a

main clause to a non-finite subordinate clause,

signifying purpose. The analysis in the guide

to such matters generally avoids the use of the term infinitive of purpose

because it is misleading. It is not the meaningless

to- particle which forms part of the traditional infinitive

in English.

Essentially, the use of to is sometimes simply a shorthand for the subordinator in order to, for example in

I came to help

He stopped to think

She interrupted to ask a question

all the instances of to can be replaced by another causal marker so we allow:

She came so that she could help

He stopped because he wanted to think

She interrupted in order to ask a question

so these are not, in this analysis, examples of catenation proper.

However, in:

I expected to be asked

She thought to congratulate her

They hoped to win

we do have real catenation because in none of these cases is it possible to replace the to with the alternatives suggested above.

We cannot have

*I expected so that I would be asked

*She thought because she wanted to congratulate her

*They hoped in order to win - Secondly, in the list that follows, it is usually possible to replace the

second verb with a noun of any kind providing the verb itself can be

or must be used transitively. In these cases, a gerund derived

from a verb is sometimes a possible alternative because it acts as

the direct object of the verb itself. Where this is possible,

it is noted.

Many verbs associated with permissibility appear to take an -ing form as a second verb but usually the case is that the -ing form is acting as a noun (as is the wont of gerunds) and is, therefore, not a verb but the direct object of the first verb. This means that verbs such as allow, permit, forbid and so on do not occur in the list which follows as we analyse, e.g.:

She allows smoking in the house

as akin to

She allows cigarettes in the house. - Finally, because catenation with the to-infinitive

often refers to a prospective event, any adverbial will normally

be interpreted as applying to the second verb so, for example,

in:

She promised to come today

the normal interpretation will be that it is today that she will come, not today that she promised. Any ambiguity can be removed by moving the adverbial and having, e.g.:

Today, she promised to come

which only has one interpretation.

The verb agree also creates the ambiguous sense in:

She agreed to start immediately

in which it is not clear whether the adverb modifies agree or start.

Again, moving the adverb makes things clear so we can have either:

She immediately agreed to start

or

She agreed to start immediately

Naturally, if the adverbial itself signals future time, there is no ambiguity so:

She expected to arrive next week

has only one possible meaning.

The possible ambiguity can arise with a number of the verbs in the following list.

The following are the most common of these verbs with some notes where necessary. The list includes verbs which always take a direct object and do not properly catenate because the object is positioned between the verb and the non-finite form.

| Verb | Example | Notes |

| advise | He advised me to try | This verb is almost invariably used with a direct object. |

| afford | We can afford to buy the car | Almost invariably with can.

This verb takes a noun as a direct object but not a gerund

so we allow: We can afford a new car but not *We can afford going on holiday |

| agree | They agreed to differ | In AmE usage, this verb is

transitive and that is becoming common in BrE, too so we

allow also: We agreed the plan. However, like afford, a gerund as the object is not allowed. |

| aim | We aim to take a winter holiday | This is akin to We are going to take a winter holiday and is a prospective use. |

| allow | I allowed him to go | The verb let takes the

bare infinitive (see below). This verb has a non-catenative use and allows a gerund as the direct object, e.g.: Do they allow fishing here? In the example, here the catenation has been interrupted by the direct object. |

| appear | She appeared to agree | This verb is also copular as in, e.g., She appeared agreeable. |

| apply | They applied to leave | This verb is intransitive so no direct object is allowed. |

| arrange | They arranged to arrive early | This verb is

transitive and often followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. The hotel arranged parking for us. |

| ask | John asked to leave | This is a transitive verb and allows any number of direct objects, some of which, such as permission are deverbal nouns. It cannot, however, take a gerund as its direct object. |

| attempt | She attempted to interrupt | Compare try (below) which varies in meaning. |

| be bound | She is bound to disagree | This is a marginal modal verb

expressing likelihood usually, but can express obligation as

in, e.g.: I am bound by my promise. |

| beg | I beg to differ | Formal use and collocation is limited to a few verbs (disagree, deny etc.). |

| begin | It began to rain | Also possible with the -ing form with no change in meaning. |

| care | Would you care to dance? | This verb is nearly always used in the negative or in questions only: i.e., non-assertive uses. |

| cease | I ceased to argue | The verb stop catenates

with an -ing form. With the infinitive, the interpretation of

stop plus to is

in order to. This is not the case here and I ceased to look at the map does not mean the same as I stopped to look at the map We allow an -ing form as a direct object with this verb e.g.: I ceased arguing |

| chance | I chanced to meet him in the hotel bar | Formal use. |

| choose | I chose to stay silent | This verb is

transitive and often followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. We chose flying over taking the train |

| condescend | They condescended to talk to me | Compare deign. This

verb can be used (rarely) in the negative: She condescended not to complain. |

| consent | Do you consent to pay the money? | This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. We consented to his practising the piano in the evenings |

| contrive | He contrived to get lost somehow | Compare manage. |

| continue | He continued to complain | Also possible with the -ing form with no change in meaning. |

| dare | I dared to ask why | This is a semi-modal verb. |

| decide | We decided to go | Compare go. |

| decline | I decline to comment | No negative use. |

| deign | She deigned to invite them | Formal use (compare the synonymous

condescend). The difference is that this verb

cannot be used in the negative: *She deigned not to argue. |

| demand | I demand to come | Often in passive clauses: I demand to be heard. |

| deserve | She deserves to win | This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund or other noun as the object as

in, e.g. She deserved congratulating / congratulation Here the subject of the sentence is not doing the congratulating so the gerund form is acceptable. |

| determine | I determined to go | This is a formal use.

Frequently the participle adjective is used as in, e.g., I am determined to go. |

| encourage | She encouraged me to ask | The verb is also used with a gerund

as the direct object, e.g.: She doesn't encourage smoking in the hotel. The verb is always transitive so very often split from the next by the direct object (see below). |

| endeavour | I endeavoured to help | Compare try which can also be followed by the -ing form. This verb cannot. |

| elect | She elected to stay | |

| expect | Mary expected to fail | This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. She expected travelling would be difficult at the weekend and by a simple noun: She expected rain. |

| fail | Mary failed to win | |

| forbid | I have forbidden him to come | This also works with the gerund as

a direct object in,

e.g. I forbid smoking here Again, the verb is always transitive so split from the next verb by the direct object (see below for the passive use). |

| forget | I forgot to say thanks | See below for the changed meaning with the -ing form. |

| happen | I happened to see her | This is also considered a marginal modal auxiliary verb. |

| hasten | I hasten to add | This is now almost confined to the set expression with to add or to say. |

| help | I helped to finish the work | The bare infinitive can also be

used as in, e.g. Can you help finish? See also below for can't help plus the gerund. |

| hesitate | I hesitate to complain | |

| hope | I hope to see you there | |

| instruct | She instructed them to wait | This verb is almost invariably used with a direct object. |

| intend | I intend to see him today | More rarely, this verb is followed by an -ing form with no change in meaning. |

| invite | I was invited to speak | This verb is almost invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| learn | I learnt to swim at school | |

| long | I long to see her again | |

| manage | They managed to arrive on time | |

| mean | I meant to ask but forgot | Here the verb means intend but it can be followed by an -ing form when the meaning alters to involve. |

| move | I move to adjourn | A rare and formal meaning. |

| need | I need to leave soon | This is a semi-modal verb expressing obligation. |

| neglect | I neglected to tell her | This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. She neglected watching the children or by a simple noun: She neglected her duty. |

| oblige | She was obliged to do the work | This verb is invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| offer | I offered to help | |

| omit | I omitted to ask that question | This verb is transitive and often

takes an object gerund or noun phrase such as: I omitted painting the doors She omitted the attachment |

| order | He ordered me to leave | These verbs are invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| permit | John was permitted to stay | |

| persuade | I persuaded her to pay | |

| plan | I planned to go | Compare intend and mean. |

| prepare | I prepared to travel | |

| press | I pressed him to help | This verb is invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| pretend | They pretended to work | |

| proceed | I proceeded to start at once | Formal use. Unlike the synonymous start and begin, it cannot catenate with a an -ing form. |

| promise | I promise to help | |

| propose | I propose to go | This is a slightly formal version of plan or intend and the verb can also be used to mean suggest when it is used with an -ing form. |

| refuse | I refuse to help | |

| remember | I remembered to ask | See below for the changed meaning with the -ing form. |

| remind | They reminded us to come | This verb is invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| request | She requested them to be quiet | This verb is invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. It is quite rare and formal. |

| resolve | I resolved to wait | |

| seek | I sought to explain | |

| seem | She seemed to be happy | Compare appear. This verb is also frequently a copula. |

| start | She started to eat | This verb can be used, like begin, with an -ing form with no meaning change. |

| strive | I strove to understand | Formal use. |

| struggle | The company struggles to survive | |

| swear | Mary swore to tell the truth | |

| teach | He taught me to swim | These verbs are invariably used with a direct object and frequently in the passive voice. |

| tell | I told her to try | |

| tempt | I was tempted to leave | |

| tend | They tend to stay up late | This is also considered a marginal modal auxiliary verb. |

| threaten | They threatened to sue | |

| trouble | Please don't trouble to drive | This is almost exclusively used in the negative. |

| try | Try to be more helpful | See below for the changed meaning with an -ing form. |

| undertake | They undertook to act as agents | |

| volunteer | John volunteered to help | |

| wait | I waited to see what she would say | This is sometimes followed by

and plus a verb as in, e.g., Wait and see. The form is sometimes a subordinate clause: I waited in order to see what she would do with a subtle change of meaning. |

| want | I want to go now | |

| wish | I wish to complain | Formal use. This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. She wished flying were possible |

| would like | Would you like to come? | By their nature, many structures with would follow this pattern. |

| The following only

catenate in the passive. In the active form, the

object is placed between the verb and the non-finite form. Almost all the uses are more formal. |

||

| allow | They were not allowed to come | |

| ask | She was asked to keep it | |

| call | They were called to explain | Formal use. |

| command | I was commanded to stay | |

| compel | John was compelled to explain | |

| destine | He was destined to fail | It is often difficult to distinguish this use from a predicative participle adjective. |

| encourage | They were encouraged to come | This is non-catenative when the

participle adjective is used: The were encouraged by the result. |

| entitle | I am not entitled to complain | |

| forbid | I was forbidden to enter | Actively, this verb is also used with the gerund as a direct object. |

| force | She was forced to work late | |

| instruct | I was instructed to remain | |

| intend | They were intended to have the money | See above for the verb used in a slightly different sense. |

| invite | She was invited to attend | |

| move | I was moved to complain | The sense here is different from the example of move above. |

| order | They were ordered to appear | |

| permit | They were permitted to enter | |

| press | She was pressed to respond | |

| prohibit | She was prohibited to come | This is an unusual use and the preferred form is the prepositional phrase with from + a gerund. |

| request | You are requested to leave | |

| require | She is required to remain | |

| teach | I was taught to swim | |

| tell | They were told to stay | This verb is

transitive and may be followed by a gerund as the object as

in, e.g. She was told staying another day was possible |

| tempt | I was tempted to go | Arguably, this is a participle adjective use of the verb form. |

|

Verbs followed by the -ing form or gerund |

| I enjoy relaxing in the pool |

These verbs consistently, not invariably, refer to past experience or to a

retrospective view of events.

For example, if one says:

She admitted stealing the money

it is clear that the admission follows the theft and in, e.g.:

I hate standing in a queue

the clear implication is that the speaker has experience of standing

in a queue and hates it. Compare:

I would hate to hurt his feelings

which is clearly a prospective use and the verb catenates with the

infinitive.

This is an unreliable rule of thumb and there are many exceptions.

The other aid to memory is that the majority of verbs used with a

gerund can just as easily (often more naturally) be followed by a

direct noun object. As a gerund is often described as a form

of noun, this is unsurprising. In fact, in many cases below

where it is seen that the retrospective-prospective 'rule' is

abrogated, a better analysis may well be that the verb is being

followed by a noun-like direct object. That is often simpler

for learners to understand because they are familiar with, e.g.:

I left the keys on the table

and it is a short step to the figurative use in:

I left doing the cooking till later

Not listed here are phrasal and prepositional verbs because, with

rare exceptions they are always followed by the gerund.

A source of difficulty here is that some transitive verbs

normally followed by the to-infinitive can also take a

verb with -ing as the direct object so, for example,

we see:

I omitted writing the label on the box

I offered flying as an alternative to driving

They permitted smoking in the theatre

He taught woodworking at the school

and so on.

In these cases we have the -ing form acting only as a noun

phrase and all can be replaced with non-verbal nouns. It is a

gerund by the definition we have above. All

those verbs appear in the list above as being followed by the

to-infinitive.

In many cases in this list, it is clear that the -ing form

is often acting as a simple noun complement and there is little

sense of true catenation.

| Verb | Example | Notes |

| acknowledge | They acknowledged making a mistake | |

| admit | They admitted stealing the money | |

| adore | I just adore watching them | |

| advise | They advised waiting a little | This appears to break the prospective rule but, arguably, is a verb which can take a nominalised clause as the direct object. |

| appreciate | I appreciate receiving the help | |

| avoid | I can't avoid thinking about it | Compare the use of help in this meaning. |

| can't bear | I can't bear talking to him | Confined to negative and interrogative uses (i.e., non-assertive forms). |

| complete | They have completed repairing the car | Arguably, a case of the gerund as a

nominal object. Compare: They have completed the repairs. |

| consider | I considered taking the car | These are prospective and

break the 'rule'. However, the uses are all, arguably, with the gerund used as the direct object. Compare: I considered the offer I deferred my decision We delayed the celebration. |

| defer | I deferred making a decision | |

| delay | We should not delay opening | |

| deny | I deny taking the money | |

| detest | I detest queuing for things | Arguably, with all

four of these verbs the -ing form is a gerund and

can be replaced by any other noun so we can have: I detest avocado I dislike bananas She enjoys her food but in, e.g.: I dislike arguing with him we have a catenative structure. The verb dread appears to break the prospective rule but the feeling is based on some previous knowledge or experience. (There is a prospective use of dislike which predictably takes the to-infinitive form as in, e.g.: I dislike to have to tell you that ...) |

| dislike | She dislikes arguing with people | |

| dread | I dread meeting his mother | |

| enjoy | They enjoy learning French | |

| entail | The work entails rewriting the program | Arguably, a case of the gerund as a

nominal object. Compare: The work entails a lot of expense. |

| escape | He escaped being called up | |

| fancy | I fancy seeing a film | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule' although it is arguably premised on seeing

films before. It is also arguably a verb which takes a

nominalised object or a simple noun as in: I fancy some lunch. |

| favour | She favoured waiting a little | This appears to break the

prospective rule but, arguably, is a verb which can take a

nominalised clause as the direct object. Compare: She favoured the restaurant in the market place. |

| finish | They have finished painting the house | Arguably, a case of the gerund as a

nominal object. Compare: They have finished the painting. |

| forget | I forgot (about) meeting her | See above for the changed meaning with the to-infinitive. |

| hate | I hate teaching | This is a gerund use. For hate + to-infinitives, see below. |

| can't help | I can't help thinking about it | Usually confined to negative or interrogative (i.e., non-assertive uses). |

| (can't) imagine | I can't imagine living with her | This is often, but not invariably,

used in the negative with can but assertive forms

are also seen: I can imagine living here. |

| imply | It implies spending even more money | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule' but, arguably, is a verb which can take a

nominalised clause as the direct object. Compare: It implies a good deal of work. |

| involve | It involves travelling to Russia | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule' but, arguably, is a verb which can take a

nominalised clause as the direct object. Compare: It involves a lot of expense. |

| keep | He keeps arguing with me | |

| leave | I left doing the work till later | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule'. Arguably, a case of the gerund as a nominal object. Compare: They have left the dog outside |

| like | I like talking to them | |

| loathe | She loathes eating out | |

| love | I love living here | |

| mention | He didn't mention seeing her | |

| mind | I don't mind waiting | Usually used on the negative or, + would, in questions. |

| miss | I miss working with them | |

| practise | She is practising playing the piano | Often the verb takes a direct noun

object: She is practising the flute. |

| prefer | I prefer eating late | This can be used with the to-infinitive with little change in meaning (see below). |

| quit | I have quit smoking | Mostly AmE usage and, arguably, the

use of the gerund as a direct object: She has quit her job. |

| recall | I recall seeing him | Compare remember. |

| recollect | I recollect asking | |

| recommend | I recommend asking her | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule' but, arguably, is a verb which can take a

nominalised clause as the direct object. Compare: She recommended the restaurant in the market place. |

| regret | I regret asking her | See below for the changed meaning with a to-infinitive. |

| remember | I remembered meeting her | See above for the changed meaning with a to-infinitive. |

| require | I do not require telling twice | |

| resent | I resent waiting in the cold | |

| resist | I can't resist laughing at her | Almost always in the negative with can't. |

| resume | We resumed working at 5 | Unlike start and begin, this verb cannot be used with the to-infinitive. |

| risk | He risked losing everything | |

| see | I can see knowing for certain is better | |

| shun | She shunned meeting them | This is a rare use. |

| (can't) stand | I can't stand walking in the wind | This is almost solely used in the negative and with the modal auxiliary verb. |

| stop | Please stop talking | This is a prospective use and

breaks the 'rule' but, arguably, is a verb which can take a

nominalised clause as the direct object. Compare: She stopped her presentation. |

| suggest | I suggest waiting a little | Like recommend, this verb takes a

direct object noun phrase, too: I suggest the fish. |

| tolerate | I can tolerate working with them | This verb often takes a simple noun

direct object: I can't tolerate his behaviour. |

| try | Try using a heavier hammer | See above for the changed meaning with a to-infinitive. |

| understand | We understand getting the right price is vital | |

| want | The window wants cleaning | BrE usage. |

| The following only catenate marginally because a possessive determiner (or, informally, an object pronoun) is inserted between the verb and the non-finite form. | ||

| excuse | I can't excuse her insulting me | In all these cases, the

use of the -ing form may be considered as the

gerund acting as a direct object of the verb so we can also

encounter, e.g.: I can't excuse rudeness Can you explain the problem? Please forgive any mistakes He won't pardon errors That won't prevent the leaks We don't understand the instructions |

| explain | Can you explain their leaving? | |

| forgive | Please forgive my asking | |

| pardon | I can't pardon her swearing | |

| prevent | I cannot prevent your going | |

| understand | I understand her leaving early | |

|

Verbs followed by the either an -ing form or to-infinitive with no (or very little) change in meaning |

|

I started making mistakes when I began to get tired |

There are a few verbs which can be followed by either the to-infinitive or an -ing form with no change in meaning. Sometimes one form is more common and that is noted here.

|

|

|

Verbs followed by the either an -ing form or to-infinitive with a change in meaning |

|

try taking a painkiller or try to eat something |

A few polysemous verbs vary in meaning depending on whether they are followed by an -ing form or a to-infinitive. It is here that the prospective - retrospective 'rule' comes into its own.

|

|

|

Verbs followed by to and an -ing form |

| He is accustomed to speaking to groups |

A few verbs are followed by to plus an -ing

form. They may alternatively simply be analysed as the use of

a gerund after the preposition to (as is entirely normal)

in the same way that we have a gerund following prepositional verbs

such as:

I depend on receiving the money

He can't conceive of arriving late

They complained about eating so early

etc.

In the following list, object to and commit to may

certainly be analysed in that way.

This is almost the complete list (we think):

|

|

|

Verbs followed by a bare infinitive |

A few verbs can catenate with the bare infinitive although in one case (help) the to-infinitive is also possible. Here's the list:

|

|

|

Coordinated verbs and ellipsis of and |

| go jump in the lake |

The verbs come and go are often, it is averred,

followed by the bare infinitive as in, e.g.:

Come have a drink

Go take a seat at the front

Please come sit by me

You should go see

etc.

However, these are not cases of simple catenation because they are,

in fact, examples of the ellipsis of a conjunction. All these

examples are, in the full form:

Come and have a drink

Go and take a seat at the front

Please come and sit by me

You should go and see

The reason for excluding these forms from cases of true catenation

is that the senses of the two verbs are not connected, they are

simply coordinated and could be expressed in separate sentences or

clauses.

We can equally well have, therefore:

Please come in. Have a drink

Go to the front and sit down

Come over here and you'll be able to sit down by me

You should go so that you can see

The other part of explanation is that these two verbs do not, in

reality, catenate at all in the sense of the lists above. Both

are used with coordination expressions signifying purpose or

causality. We can, therefore, rephrase all the examples as:

Come so that you can have a drink

Go with the aim of taking a seat at the front

Please come in order to sit by me

You should go so you can see

The verbs wait and see and come and

look are frequently

coordinated as in, for example:

We must wait and see what the weather's like

Come and look what I have found

but with other verbs, wait and come take the to-infinitive

as in, e.g.:

I will wait to hear from her

I waited to eat until she arrived

I came to help

She came to believe him

etc.

The verb try is also frequently used colloquially

coordinated with others so we hear (but rarely read):

Try and help

Try and see if you can come

etc.

but in more formal uses, in this meaning try is usually

catenated with the to-infinitive.

|

Causative verbs |

| Make it so |

We poured some doubt at the outset of this guide on the assumption that verbs which do not form uninterrupted chains are actually definable as catenative in the true sense. However, some causative verbs are seen that way so they are included here.

Three, and only three, causative verbs catenate with the bare

infinitive: have, let and make.

For example:

She had the boy re-do his homework

She let the children go home early

They made the people wait too long

and that seems simple enough.

However, the direct object in these sentences breaks the chain.

There exists, however, a nasty colligation trap for the unwary which

does concern catenation.

In the passive, the case is altered and the to-infinitive

substituted for the bare infinitive with only two of these verbs (have

and make but not let) and that is wholly

non-intuitive, causing problems for learners. We get,

therefore:

The boy was made to re-do

his homework

The children were let go home early

The people were made to wait too long

Moreover, let is different in allowing a passive

infinitive as in:

They let the dogs be walked by the neighbours

and neither make nor have can be used that way so

we do not allow:

*They made the dogs to be walked by the neighbours

or

*They had the dogs be walked by the neighbours.

For more on the causative, see the guide, linked below.

|

Verbs of perception |

| I can hear splashing |

Again, the use of many of these verbs requires a direct object to break the catenation so they are not stricto sensu catenating forms. However, ...

There are a number of verbs, often lumped together in a single

group, unfortunately for learners, which refer to perception and

catenate with the bare infinitive in some cases.

Here's a non-exhaustive list:

- general perception

- detect, discern, miss, note, perceive, sense, spot

- seeing

- catch (sight of), espy, examine, gaze (at), glimpse, inspect, look (at), notice, observe, see, stare (at), view, watch, witness

- smell

- smell

- touch

- feel

- hear

- hear, listen (to)

The list is quite unbalanced, as you see / perceive / notice etc.

because most of our sensory perception is visual.

Added to the mix is that some, such as listen, observe, examine

are active in the sense of purposeful but others such as

see, hear and smell are often passive and

non-purposeful. The distinction is not always clear to

learners whose languages may differ.

These verbs can take either a bare infinitive or, slightly more

formally, and irregularly, an -ing participle clause.

The key is often to whether reference is to the whole action or a part of

it, usually. For example:

I saw him drink the beer

implies that I saw the whole action, from the full to the empty

glass, whereas:

I saw him drinking the beer

implies that I only saw a part of the action which started before

and finished after my observation.

Equally, there is a difference between:

I heard her sing at the concert

and

I heard her singing upstairs

in which the first implies that I watched the whole performance and

the second that I heard only part of her singing.

For example:

| I detected John asking Mary | We inspected the engine start / starting |

| I discerned food cooking | They looked at the sun rise / rising |

| I missed the food cooking | I noticed the ground move / moving |

| I noted the people come / coming | They observed the team play / playing |

| She perceived the class misbehave / misbehaving | We stared at the man cycling |

| I sensed the mood change / changing | They viewed the bar open / opening |

| They spotted the earth shake / shaking | We watched John paint / painting the picture |

| We caught sight of the tree falling | I witnessed the accident happen / happening |

| They espied the cook leaving by the back door | She smelled the food cook / cooking |

| We examined the class work / working | They felt the house shake / shaking |

| They gazed at the moon wax / waxing | We heard the man move / moving |

| I glimpsed the door open / opening | We listened to John play / playing piano |

As with causative verbs, however, a fly resides in the ointment

because when we make any of the sentences passive, the option has to

be the to- infinitive not the bare infinitive or the

participle form.

So it is that we get:

They were heard to move

The food was seen to cook

The house was felt to shake

and so on.

And not:

*The cook was seen leave

*The house was felt shake

*The accident was witnessed happen

That is fully non-intuitive for learners, causes problems and needs

to be taught and practised.

|

Teaching the forms |

Teaching in this area is undeniably challenging especially when

one considers that many languages do not share the characteristics

of English either having no infinitive form at all (like Greek) or,

like French and many others, having only a single form of the

non-finite with no distinction between, e.g., to smoke and

smoking in that sense.

Learners whose first language only has one non-finite form to choose

will often select the infinitive so we hear errors such as:

*I dislike to do that

or they may settle on the -ing form as their sole choice

and say:

*I expected for going

A third possibility is that, in some despair, learners will choose

the form at random.

There are some possible ways to help:

- Aiding noticing of chunks:

- Whenever a text is used, for whatever purpose, it is useful if

learners can be helped to notice chunks of language

which they can commit to memory and there are some obvious

examples in the lists above:

look forward to seeing

beg to differ

chance to meet

happen to see

etc.

It is also worth taking the time to check whether a verb is catenative and what usually follows it. That way, verbs which are followed by the to-infinitive can be taught with to included in the chunk so, instead of teaching

arrange, choose, deserve, expect

as single words, teaching

arrange to, choose to, deserve to, expect to

helps considerably.

This is similar to the ways in which one might approach phrasal and prepositional verbs.

The danger with this approach is, however, that many of these verbs are transitive and take a direct object so learning them as chunks can lead to error such as:

*I arranged to a holiday

They may also be followed by a nominalised clause and, again, there is no place for to in such constructions and the approach may produce error, for example:

*I expect to she will be there. - Awareness-raising of the rule of thumb

- We saw above that the to-infinitive generally is

prospective in nature so, for example:

I want to go

I intend to go

I plan to go

I arranged to go

I determined to go

I chose to go

I decided to go

I expected to go

I hoped to go

I forgot to go

all refer to the future after the main verb.

The -ing, gerund form, is often used with verbs that refer to past experience or to past events so, for example:

I forget talking to her

I regret upsetting her

I deny taking it

I hate waiting in queues

I loathe eating out

I dislike swimming

I recall seeing the film

all refer to the speaker's past experience or to events that precede the main verb.

This is by no means an infallible rule and there are numerous exceptions but it takes some of the guessing out of the equation. - Awareness-raising of synonymy and antonymy

- Verbs which are synonymous (or nearly so) or antonymous will

often share characteristics regarding catenation so, for

example:

hate, love, like, loathe, enjoy, detest, adore

are all followed by the -ing form

and

intend, mean, plan, arrange, promise, swear, long, hope

and

compel, command, instruct, force, order, encourage, forbid, permit

are all followed by the to-infinitive.

If a new verb is encountered and the meaning is similar to one already known, it is often helpful to know that it is likely to catenate in the same way. - Not being too technical

- We saw above that true catenative verbs abut each other in

sequences with no intervening object so while, e.g.:

I compelled him to stay

is not, technically, catenative because the object breaks the chain

He was compelled to stay

is catenative because the verbs follow in sequence.

However, for teaching purposes, whether there is an intervening object or not makes no difference to the basic structure of the clause and can be ignored.

Nevertheless, when an intervening object is involved, especially if it is a long one, we need to alert learners so that they can notice the basic structure in for example:

She asked my brother, my two sisters and myself to come to her party.

She can't stand the neighbours and their friends continually having parties. - Using -ing form, noun formed from a verb or gerund

- We saw above that there are times when verbs will combine

with a gerund or with an infinitive depending on how the

following word is seen. As a noun in, for example:

She forbade smoking in the room

or

He was forbidden to smoke in the room

In cases such as these, it may be better to tell learners that we have a noun in the first example, formed from the verb and a verb proper in the second.

|

Pronunciation |

By definition catenative verbs occur in connected speech so,

apart from the usual considerations of getting the pronunciation of

individual sounds right, it is worth considering what features of

connected speech may be present in any catenated clause.

There are no pronunciation issues which are unique to catenative

verb constructions but it is as well to be aware of what to teach in

this area if learners are to sound natural.

- The weakened form of to.

The to-infinitive is almost always pronounced with a weakened form of to so we get, for example:

She wanted to go

They waited to see

Mary expected to take the train

with to pronounced as /tə/ in all cases (/ˈwɒn.tɪd.tə.ɡəʊ/, for example). - Elision, gemination and twin sounds

If the first verb ends in a /t/ sound, there is a strong tendency to elide one of /t/ sounds altogether and we get, e.g.:

hoped to be there

pronounced as

/həʊpt.ə.bi.ðeə/

there is a case to be made that in careful speech the sound may be very slightly lengthened (that's gemination) so we get the same phrase pronounced as

/həʊptː.ə.bi.ðeə/ with a slightly longer /t/ sound than is normal.

Alternatively, and much less frequently, in careful speech, both /t/ sounds are present as in:

/həʊpt.tə.bi.ðeə/ - Assimilation and elision

This is a common feature of connected speech certainly not confined to catenative verbs. Even when the first verb does not end in a /t/ sound but, as is frequently the case, with a /d/, some assimilation or even full elision of the /t/ of to is noticeable so we get:

wanted to be there

pronounced as

/ˈwɒn.tɪd.ə.bi.ðeə/ - Catenation

This is, of course, the other use of the term as it applies to connected speech phenomena and means that instead of

regret asking

being pronounced as

/rɪ.ˈɡret.ˈɑːsk.ɪŋ/

the /t/ may be shifted to the beginning of the second verb and it sounds more like:

/rɪ.ˈɡre.ˈtɑːsk.ɪŋ/

This is not a common feature and probably not one on which to dwell in the classroom.

Other features of connected speech may be present in any set of catenative verbs that you are setting out to teach so checking for such issues at the planning stage can avoid problems later.

| Related guides | |

| PDF document 1 | this is a downloadable file of the lists in this guide |

| PDF document 2 | this is a simpler and less accurate list from the initial plus area which has two lists of verbs, followed by either -ing forms or the to-infinitive |

| infinitive: essentials | a simpler guide in the initial training section |

| causative | for a guide to causative structures and verbs including make, let, have |

| semi-modal auxiliary verbs | for uses of verbs such as dare, used and need and some marginal modal auxiliary verbs |

| infinitives | a more detailed guide in the in-service section |

| finite and non-finite forms | a guide to the difference |

| multi-word verbs | for more about transitive and non-transitive uses of prepositional verbs |

| gerund and infinitive | a basic guide in the initial plus section with some other teaching ideas and an example text |

| nouns | for more on how verbal nouns are formed |

| colligation | a guide to how colligating words share structural characteristics in general |

References:

Chalker, S, 1984, Current English

Grammar, London: Macmillan

Hoey, M, 2003, What's in a word?, Macmillan, MED Magazine,

Issue 10, August 2003

McLeod, D, n.d., Practising English, Ramsgate, UK: Home

Language International