Problem solving for Academic Managers

This guide will not solve all your problems. Sorry about

that.

What it is intended to do is to give Academic Managers, whatever

their level of experience and wisdom, some ways of thinking about

what we loosely call problems and acting based on thought rather

than instinct and inclination.

Right now, on a piece of paper, write down three things that have happened to you (not necessarily in your professional life) that you would classify as problems. We'll come back to your list from time to time.

|

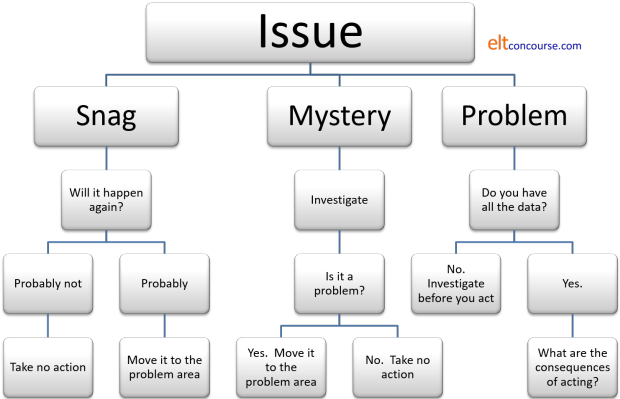

Defining the issue: what counts as a problem? |

This may seem obvious but it isn't. Consider these three scenarios and decide which one(s) is/are (a) problem(s). Then click here.

- John was 20 minutes late this morning.

- Photocopying costs have doubled this month.

- We have too many students for our number of teachers.

- John was 10 minutes late this morning.

- This is a snag, not a problem. It may have been slightly irritating for the Academic Manager (or somebody) to have to cover his teaching timetable for 20 minutes but it doesn't count as a problem. He's here now and the day is on track.

- Photocopying costs have doubled this month.

- This may appear to be a problem but it isn't certainly one until we have investigated what caused the increase. If it was the introduction of a new course or a sudden rise in student numbers, it may simply be a consequence of something else and unavoidable. Before it qualifies as a problem, it's a mystery that needs to be investigated.

- We have too many students for our number of teachers.

- Now this really is a problem because urgent action has to be taken. Either we cut down the number of students (not a popular decision with the financial manager) or we have to employ more teaching staff (a slightly less unpopular solution with the financial manager) or we raise maximum class sizes (popular with the financial manager, less so with teachers and students).

So, we now have rule 1 for problem solving:

|

Rule 1: define |

Decide if the issue is a snag, a mystery or a problem.

- snags may develop into problems if they aren't watched. If John arrives 20 minutes late every Monday, then we need to talk to him about his contract of employment.

- mysteries need attention but aren't urgent. They can be symptoms of problems but we don't know until we gather the data.

- problems need attention.

Look again at your list of three 'problems' and decide if, on this basis, you can discard any of them.

|

The pale blue dotIf you inspect the picture to the left carefully, you

will discover a small, pale, blue dot near the centre. |

During a public lecture at Cornell University in 1994, Carl Sagan presented a similar image taken from around 6 billion kilometres away, beyond the orbit of Pluto and said:

That's here. That's home. That's us. On it, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever lived, lived out their lives. The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every hopeful child, every mother and father, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived there – on a mote of dust

The point of this little astronomy lesson is to encourage a sense of perspective. Problems arise, problems are solved. It's what happens in schools. This is a language course, not a plane crash.

There are consequences to losing a sense of perspective and rushing

in to fix problems before the causes and possible effects of any

solution are clear.

Here's a cautionary tale:

Kamarina was an ancient city on the southern coast of Sicily in southern Italy which had a serious problem arising from a mystery. During the 5th century BCE, the Kamarinians suffered from a plague (probably malaria) which some associated with the marshland to the north of the city. A proposal was made to drain the swamp and, despite the opposition of the local oracle, this was done. Once the marsh had been drained, there was nothing to stop a Carthaginian army from assaulting the city. They marched across the now-dry marsh and destroyed the city, wiping out everyone.

The point of the history lesson was slightly different. It was intended to demonstrate the awful consequences of not thinking things through. It is an example of the Law of Unintended Consequences at work.

|

Rule 2: stand back and consider the consequences |

All actions have consequences. For example:

- If you need to move a student from one

class to another, consider what consequences that will have on

the rest of the group.

Will you encourage others to demand a change of class?

Will the group become unbalanced and more difficult to teach? - If you need to change a teacher's timetable, what

consequences will that have?

Will the teacher earn less?

Will other teachers demand similar treatment?

Will this affect other people's timetables? - If you feel that your course materials are getting dated,

what will the consequences be of introducing a whole set of new

ones?

Will the teachers use them?

What else will you have to buy?

What else will become redundant: teachers' lesson plans, supplementary materials on so on?

What will the subtraction of this amount do to your budget? What else will you no longer be able to buy? - If you feel your placement test is not working well, what

will happen if you change it?

Will you be able to mark it quickly?

Will it be as reliable?

Will it be parallel with the old test?

Will it test the same things?

Will it take longer?

and so on. For every action there are effects; some good, some bad, some unpredicted.

|

Gather the data |

Before you act on a problem, you need to harvest some information. Often, this will reveal an underlying issue and you will be in danger of treating the symptom, not the disease.

Here's another little historical parable to consider.

In Philadelphia around the 1880s a scientist called Goodspeed

discovered the shadow of three coins on a photographic plate, threw

it away and re-started his experiments.

Around the same time, another investigator, Crookes, found that the

photographic plates he kept in his laboratory had become fogged and

returned them in disgust to the manufacturer.

On November 8th 1895, a man called Röntgen noticed a similar effect

and became the celebrated discoverer of X-rays.

When asked what he thought when he noticed the effect, he said, "I

did not think. I investigated."

Here are some examples a bit closer to home:

- A learner demands a sudden change of class. Up until

now he has been happy and hardworking where he is, but he is now

insistent that the level is too high for him.

You can, of course, act immediately and, consulting with his teacher, move him to another group. Problem solved? No.

He is too fluent for the other group and intimidates some of the quieter students in it. The teacher of his new class is very disappointed and not a little irritated that you have foisted the student on her.

A little investigation before you acted would have revealed that he has, in fact, struck up a loving relationship with someone in the class at a level below and that is why he wanted to move. It was nothing to do with the level of the group at all. You have created a problem where none existed. - A group leader / representative has complained that one of

the teachers has been very rude to a colleague and he is

threatening to report this to the main (and important) school's

agent.

You feel that this entirely in character for this teacher, who has been rude in the past to you and colleagues, so you talk to the teacher in question sternly and tell the group leader that it won't happen again. Problem solved? No.

An investigation would have told you that the group leader's colleague speaks very little English and was unable to understand that the teacher in question was giving him very good advice about something and not being rude at all.

Now you have an embarrassed group leader, an unhappy teacher and a confused group leader's colleague. - A teacher comes to you asking that a student be moved out of

his class because she can't keep up with the work. You

talk to the student and she seems to agree that the class is

difficult for her so you move her down a level to a new group.

Problem solved? No.

Investigation would have told you that the student was correctly placed all the time. The problem was that the teacher had taught her in the last course and she has seen many of his materials. He is unhappy at the thought of producing or finding new materials because of this.

Now you have a misplaced student and a teacher who thinks he has hoodwinked you.

You can probably think of examples of your own when something done in good faith has had consequences which could have been avoided with a bit more thought and investigation.

|

Rule 3: do not act without the facts |

Acting in the absence of the information is perilous. As the famous law states,

The time it takes to rectify a situation is

inversely proportional to the time it took to do the damage.

(Drazen's Law of Restitution)

Sometimes, of course, once the damage is done, no rectification

is possible.

There is a natural tendency, when faced with what clearly is a

problem, to flex your managerial muscles and be seen to be doing

something. It is a tendency worth keeping under control.

Before you go on to the last part, there is one question you

should always pose to yourself before you take action to solve a

problem:

Am I acting in full understanding of

all the facts because I judge my action will

solve the problem

or am I acting because I want to be seen to be doing something?

If it is the second part of that that gets the nod, you probably

should not be acting at all. Very little is that

urgent.

|

Back to your three problems |

It may be the case that none of your original problems has survived this far. That is probably a good thing.

If the problems are still with you, there are some obvious

questions to answer.

Here's a route map: