Correcting learners

|

Correcting learners is a key teaching skill. It can

be overdone and some learners feel it gets tedious so handle with some

care.

In this guide, we are mostly concerned with correcting learners' production.

However, if you have followed the guide to the essentials of error

analysis (linked below), you will know that learners also make receptive errors.

That is to say, they misunderstand or misinterpret what they hear or

read.

The following assumes you have followed the essential guide to error and

understand terms such as referential, covert, phonological and

syntactical error etc.

If you don't try that guide first by

opening it in a new tab.

|

Before you dive in |

Here is where teachers need to think on their feet. There are questions to ask whenever you hear an error in the classroom or see one in your learners' written work.

- Am I going to correct this?

- If the error isn't holding up communication and has nothing to

do with the subject of the lesson, it may be that correcting it will

lead you off on a tangent, chasing red herrings and serve to slow

down the lesson and confuse the learners. If that's the case

ignore it.

If, on the other hand, the error is impeding comprehension or is made in the language that is the target of what you are doing, then you will have to deal with it. - Do I need to correct this?

- Very often, learners can correct their own production so a quizzical look or stopping learners and getting them to retrace their steps and reconsider may be more effective than your correcting the error.

- Can anyone else correct the error?

- If the learners can't correct their own errors, perhaps someone else in the class can. If you think this is the case, give them the chance to do so.

- How will I correct?

- A last resort is normally to give

the correct answer yourself.

How we correct is next.

|

Handling spoken error |

We said above that correction is a key teaching skill and, like

all skills, it improves with practice. There are, however,

some tried and trusted methods which we can learn outside the

classroom and then apply with increasing levels of confidence and

appropriateness.

Here are some of them:

|

Looking for clues |

It is often enough just to give a few clues or hints to lead the

learner to the correct answer. This is especially the case if

you suspect that the learner can self-correct or be led carefully to

do so with questions and suggestions such as

There's

something wrong with the order of the words.

What preposition do

we need here?

What tense should this be?

Who did the work?

Are we talking about

tomorrow or today?

Is this a long 'a' sound or a short one?

and so on.

If all else fails, however, there are, obviously, times when

providing the right answer is the best approach providing you make

sure that the learner can produce the correct language independently

after you have done so.

|

Grimacing |

This only applies to times when you know for certain that

the learner can self correct. If you use the technique at

other times, for example, when the learners clearly have no idea

what the right word is, how to pronounce something or how to

form a correct bit of syntax, then you will frustrate and

irritate them. That's not good.

For example:

|

|

or |

|

| Probably not | What! | Ouch |

|

Finger correction |

This is a technique which works very well for simple syntactical

errors such as

We arrived to the hotel very late in the

evening

in which the learner has not recognised that, in English, the

verb arrive is usually followed by a prepositional phrase

with at. This is an understandable mistake

because we do say:

She came to my house

We got to the station

etc.

The technique involves using the fingers to count and stopping and

grabbing the third finger with the other hand.

The learner is then primed to notice where the error lies rather

than starting to doubt that the whole sentence is wrong (which it

isn't).

|

Phonological error: drilling and other techniques |

Phonological errors are traditionally addressed by some sort of

mini-drill and there's a guide to drilling on this site, linked

below.

A particularly useful technique, explained there is called back

chaining.

Other techniques include tapping out the rhythm of a

sentence to get the stress right or using the phonemic script (if

the learners are familiar with it) to show the difference between,

e.g., sit and seat or hop and hope (/sɪt/

and /siːt/ or /hɒp/ and /həʊp/).

Rhymes are also useful tools because if a learner can pronounce,

e.g., station then the fact that a difficult word such as

nationalisation rhymes is some help to being able to

pronounce it.

Isolating sounds is another way to help. If, for example, a

learner can correctly pronounce the short i sound in

hit, bit, sit etc. you can lead her to the pronunciation of the

second syllable in contribution quite painlessly.

|

Using time lines |

When it is clear that the concept of a tense form is in question

and learners have not grasped, especially, the relationship between

tenses, a time line can help (with presentation as well as

correction, of course.

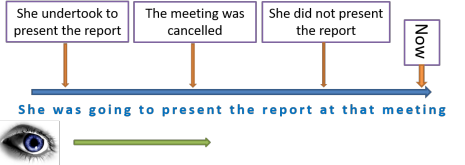

Here's an example to explain the concept of what is known as the

future in the past:

And that will work just as well for:

I was about to go out when he rang

I She was on the point of losing her temper

and so on.

There is a dedicated guide on this site to constructing and using

time lines, linked below.

|

Noticing and using the model |

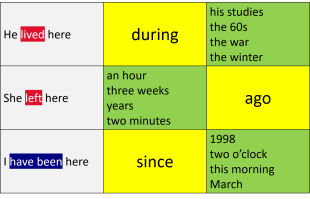

When teaching a syntactical or structural point, most people will opt for a model sentence or sentences which will exemplify the issues. For example, when teaching simple time adjuncts, people might got for displaying and explaining:

He lived here during his studies

She left an hour ago

I have been here since 1998

However, leaving it at that is not adequate if you want the learners to notice the critical issues a syntactical error is likely to arise unless you revisit the board and have something like:

He lived here

during

his studies

She left an hour ago

I have been here

since 1998

and even then you will need to expand that to something like:

and with that in front of your learners, you can easily point out:

- the correct tense form (past simple vs. present perfect)

- the prepositions (during and since)

- the postposition (ago)

- the appropriate form of time expression (events, periods, dates)

so, when they make a mistake, you can quickly point out which bit of the table they have got wrong.

This technique relies on getting learners to notice the salient features of the language.

|

Echoing |

This is more than simply repeating what a learner has just said

(which is useless and deeply irritating, by the way).

Echo correction means taking the learner's statement and stressing

the bit that you want to focus on. For example:

You said you

SEE him yesterday?

There were three CHILD?

|

Recasting |

This is a subtler way to correct and requires the learner to be

paying some attention because the aim is to get the learner to

notice the gap, not just the structure as we saw above under the

model.

Again, you have to make sure they can do that by stressing the

feature in your production which differs from what has been

produced.

For example:

Learner: I will taking the train.

Teacher: Oh, you will

BE TAKING the train.

or

Learner: I should to go.

Teacher: Oh, you should GO.

|

Delayed correction |

Correction, especially if badly times, can be interruptive and

frustrate learners who are trying to get on and communicate

something important.

So, during communicative activities, unless the error is very

serious (an preventing communication), keep quiet and take notes.

Then, when you reach the end of the activity, you can call

everyone's attention to the errors and see if they can self-correct.

If they can't, you need to backtrack, of course, because something

has gone very wrong with the teaching and learning procedure.

|

Handling written error |

One of a teacher's many chores is correcting learners' written

work. It may be a chore but learners appreciate the guidance

and help you can give when not under pressure in the classroom.

The same considerations apply here in many cases. It is not

very motivating to receive a piece of homework covered with lots of red

marks, crossings out and rewritten sections. So, try:

|

Encouraging self-correction |

Instead of correcting errors in written work, we can simply

underline them and get the learner to proofread the text and try to

correct as many as they can.

This is a rather hit-and-miss procedure, however, because learners

are often not aware of what to look for so, to help them, develop a correction code like:

It doesn't matter too much what sorts of code symbols and letters

you use, providing only that you are consistent and the learners

understand it.

You should also, of course, have a code for something which is good.

Many people use of

![]() for that.

for that.

|

Working together and peer correction |

We can encouraging peer-correction by having learners write

together (with all of them writing the same text or agreeing on the

right answers) and helping each other. We can also ask the learners to give their writing to others for

comments and correction.

Do not overdo this for the sake of authenticity. Writing is

often a skill that we practise alone.

|

Wisely ignoring error |

Just as we saw concerning spoken error in the classroom, it is

often wise to ignore some written errors.

This is especially true if learners attempt language so far beyond

their current mastery level that correcting it would be confusing

and frustrating.

It is also true if you see something which is obviously just a slip

or a typographical error.

| Related guides | |

| essentials of error | for the guide to types and sources of error |

| drilling | for a guide to one teaching technique, often employed to handle (or prevent) error |

| using time lines | for the dedicated guide to a useful presentation and correction method |

| how learning happens | for the guide to some major theories of learning |

| feedback | to see how the type of feedback which is given can affect how error is handled |

| the in-service guide | for a more technical and fuller guide to error |