Mistakes: slips and errors – an essential guide

|

We all make mistakes |

|

Slip or error? |

Traditionally in English Language Teaching, we make a distinction

between two types of mistake: an error and a slip. Errors

are caused by a lack of language knowledge or communication strategies and slips are caused by

tiredness, inattention or just having too much to think about at the

time.

For example, two of the following are just slips which can be ignored

(unless they persist) but three are real errors that may need us to do

something constructive in the classroom. (All of them are real,

noted in the classroom, by the way.)

Can you identify which is which?

Click here when you

have an answer.

- An advanced learner talking

about his father:

He go fishing every Sunday - A low-level learner describing a picture of the seaside:

There are stone stairs down to the beach - An intermediate learner summarising a newspaper report about

something which happened last week:

The house's roof is blow off - An intermediate-level learner explaining a problem:

The car won't starting because something is wrong with the engine - An upper-intermediate learner asking a classmate to pass a pen:

Please give that me

Right. Numbers 1, 4 and 5 are just slips or mistakes. It's unlikely that an advanced learner doesn't know that it should be he goes. It's also unlikely that an intermediate speaker doesn't know that won't is followed by the infinitive, not the -ing form and that an upper-intermediate student doesn't know that it should be it not that in this case.

Numbers 2 and 3, however, are real errors.

In 2. the speaker clearly doesn't have the word steps in his or

her vocabulary

In 3. there are lots of errors: the form of the

genitive (it should be the roof of the house), the form of a

passive (it should be the verb be followed by the past

participle, blown) and the tense of the verb (it should be

was or has been).

|

Two views of errorWith which of the following do you have

the most sympathy? View 1:

errors made by students are evidence that something has gone

wrong in the teaching-learning process. |

Here are some comments. There is no right answer to this question but you should know that what you believe about error is likely to affect how you handle it.

View 1: is often held by those who believe that learning a language is mostly about forming good habits and, through lots of practice and repetition, we can get to the point where we are producing correct language automatically, almost without thinking.

View 2: is often held by those who see language learning as a process of thought: learning by testing hypotheses, adjusting our theories, comparing what we say with what we hear and noticing gaps in knowledge for ourselves.

These are fundamentally different ways of seeing the process.

|

How do the different views change how we handle error? |

Well, how might they? Think for a moment and then click here.

- If you hold view 1:

- You may feel it's your duty to correct every error as soon as it's made for fear that otherwise the learners will acquire bad language habits. You may also try to avoid putting your learners in a situation in which errors are going to happen.

- If you hold view 2:

- You will probably be rather more relaxed about error and focus only on those which are important for the purposes of what you are teaching at the time or which seriously get in the way of communication. Note that none of the errors in the first list of five makes the learner's meaning unclear.

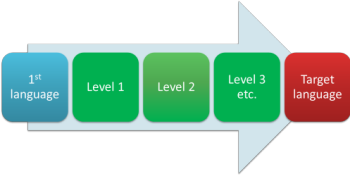

Interlanguage

This is a key concept and describes where the learners' current language mastery stands on a scale from knowing nothing of the target language to complete mastery. Diagrammatically, it can be pictured like this:

It is, of course, crucial to know where a learner's interlanguage currently is. There are three reasons (at least) for this. Can you come up with them? Click when you've made a note (or at least thought about it!).

| Reason 1: | it tells us what the learner is likely to know already and that helps us plan what to teach. |

| Reason 2: | it helps us to decide what to correct in class. There's little point in trying to correct a very elementary student who is trying to produce a complex third conditional form with a modal auxiliary verb because it will take too long and probably confuse the learners. |

| Reason 3: | it helps us to recognise whether an error should be corrected by you or whether the error can be self-corrected by the learner. |

|

Different kinds of error |

Errors come in a range of flavours.

|

Task Here are six spoken errors (real ones), two each of the three main sorts, made by learners of English. Can you say what is wrong and have a stab at describing the sorts of error that have been made? You'll need three categories for the six errors. Click here when you have done that. |

- I have done a mistake

- She comes frequently late

- I hopped I would see you

- Please close the light

- Please seat here

- Can you look my bags after, please?

We will use the technical terms for these kinds of error here but you may have described what's happening in a less technical way. That's OK, of course.

- Referential or lexical error

These describe what's gone wrong in 1. and 4.

The learner has chosen the wrong word. It should be:

I have made a mistake

and

Please switch off the light. - Phonological error

These are errors in pronunciation (probably not lexis because the learner knows the verbs sit and hope but cannot pronounce the forms correctly). The examples are 3. and 5. It should be:

I hoped I would see you

and

Please sit here - Syntax error

These are what happens when the learner gets the structure or the grammar wrong, in examples 2. and 6.

It should be:

She frequently comes late

because adverbs like this come before the main verb, not after it and

Can you look after my bags, please

because this multi-word verb cannot be separated.

|

Spotting the error |

Not exemplified above are two further important categories of error:

- Interpretive error / receptive error

This refers to the fact that learners may feel that they have understood something but have, in fact, not fully grasped what they hear or read or have, so to speak, got hold of the wrong end of the stick.

We can all make a mistake in understanding what we read or hear so it is important that we have ways in the classroom to find out whether something has been adequately understood or not. To do that, we ask questions or make sure the language has a clear context so we can judge.

Here are two examples:- Q: How long are you staying?

A: I came last Friday

In this exchange, the second speaker has interpreted the question as:

How long have you been here?

because in many languages, the question

How long are you here?

means just that. - Text:

John has had the shopping done

Q: Who did the shopping?

A: John

In this, the learners has misinterpreted what is called a causative structure. That structure signals that the subject did not do the action, someone else did.

Because the structure looks very similar to

John has done the shopping

the misinterpretation is understandable (and forgiveable).

- Q: How long are you staying?

- Covert error

If, for example, a student says,

She has been to London.

how do we know if it is right or wrong? The form looks and sounds OK but the learner might have meant:

She went to London.

or

She has gone to London.

and that's another reason we need a clear context for all the language we practise in the classroom.

To get at the sense of what the learner meant, we need to ask some questions:

Is she in London now?

When did she go?

Is she travelling now?

etc.

|

Explaining the error |

Can you think of any reasons why students may make errors?

Click here when you have thought of something.

- Ignorance

- The learner may simply have never learnt the form or the meaning and is just stabbing in the dark. This is most common at lower levels because that's where learners' needs often outstrip their abilities to produce language.

- Overgeneralising the rule

- Sometimes, when a 'rule' has been learned, learners will over-extend it. For example, if you have learned the rule to add -ed or -d to make a past tense, it seems logical to form catched. Equally, over-extending a rule might lead to the production of wonderfuller.

- First language interference

- All learners, especially adult ones, will draw on language(s)

they know to try to figure out a new one. This is most obvious

in the area of pronunciation, of course, but occurs frequently in

other areas:

Structure: the learner's first language may have a structure that looks similar but means different things. For example, the German structure of ich habe gesehen [I have seen, literally] often is better translated into English as I saw rather than I have seen. That's only one reason for finding out a bit about our learners' first languages.

Lexis: many languages, and not only European ones, have words which look the same but have different meanings. For example, simpatico in Italian means nice or friendly, sensibel in German means sensitive and un smoking in French is a dinner jacket. There are many hundreds of these so-called false friends. There's a set of exercises on this site focused on false friends.

Appropriacy: in many languages, such as Greek, it is perfectly acceptable, for example, to go into a shop and state I want ...or Give me ... with no please to soften the instruction. That will not work well in most English-speaking cultures.

The next step is, of course, knowing how to remedy the error. For that, there is a separate guide to correcting learners linked below.

| Related guides | |

| correcting learners | for what to do next |

| how learning happens | for the guide to some major theories of learning |

| feedback | to see how the type of feedback which is given can affect how error is handled |

| the in-service guide | for a more technical and fuller guide to error |

Click here for a test in this area.