How to write a Delta Background Essay

This guide will not guarantee you a Distinction grade. The grade you get will depend on content more than form but if you follow this guide, you will almost certainly get a Pass grade.

There is no detailed gloss available from Cambridge English

concerning the criteria for the assessment of the Background Essay

so ELT Concourse has produced one.

You can

get it by clicking here.

It will be useful to have it open in another tab or by your side as

we proceed.

|

What assessors sometimes say. The following are typical assessor complaints concerning Background Essays in each of the four assessment categories. This guide is intended to help you make sure they aren't levelled at you. |

|

|

|

The mechanics |

Referencing

You will need to make sure that the in-text referencing and the

bibliography follow a standard convention.

For details, go to a website for advice. There’s a good guide

to the Harvard referencing system

produced for Anglia Ruskin University that you can access

by clicking here.

Briefly, however:

For in-text references

- Books and articles

- At every point in the text where there is a particular

reference, include the author’s surname and the year of

publication with page numbers if you are quoting specific words

– for example:

In his survey of the social habits of Delta tutors, Bloggs (1998) refuted that ...

or

In his survey of the social habits of Delta tutors, Bloggs (1998: 19) states that, "I can assert without fear of successful contradiction that …"

Make sure that it is 100% clear where your writing stops and a quotation begins, either by using inverted commas or indenting the citation etc. - Websites

- You may not know the author’s name or date (but give them as above

if you do) so this is acceptable:

It has been suggested (Wikipedia (2013)) that …

For the bibliography

For ease of access, you may like to divide your bibliography into Books and Articles, Teaching Materials and Electronic resources.- Books

- List references in alphabetical order by the surname of the

first author. If the author is unknown you should use

“Anon”

For up to three authors include all names; if there are more than three, give the first author’s surname and initials followed by et al.

Provide, in this order and format: Author surname/s and initial/s + Ed. or Eds. (if editor/s), Year of publication, Title in italics, Edition (if not the first edition) as ordinal number + ed., Place of publication: Publisher

For example:

Jones, D, ed., 1995, My Teaching and Other Fiascos, 5th ed., London: Concourse publications - Articles

- Include also: full journal title, volume number (issue number) and

page numbers, for example,

Bloggs, T, 1997, Developing fluency through ferret keeping, English Language Teaching Journal, 41, 3 pp. 18-83 - Electronic resources

- E-journals – include full URL and date of access, for example:

Bloggs TA, Brown G.C., 2012, Spoken English in Weston super Mare, in The Wandering Linguist [online], p. 105. Available from: http://www.wanderling.com/1111 [Accessed 23/08/2017] - Websites

- Supply author/s or corporate body, date of publication /

last update or copyright date, available from: URL [Accessed

date], for example:

eltconcourse.com, How to write a Delta Background Essay, available from: https://www.eltconcourse.com/this page [accessed 02/11/2017]

or:

Bloggs, T, (no date), Ideas for a Creating a Happy Classroom, available from https://eltconcourse.com/training/happiness.pdf [Accessed 03/07/2017]

|

Avoiding accusations of plagiarism |

Plagiarism is a form of fraud. It can be defined as

presenting someone else's work, thoughts or words as if they were

yours. Downloading and using unacknowledged material from the

internet is included, of course.

You should know now that robust checks are in place for all essays

submitted to Cambridge. If you cheat, you will almost

certainly be found out and may be disqualified.

- You are expected to do wide reading and research on the Delta course so never be afraid to show that you have accessed a range of other people’s work – nobody is expecting you to originate all the ideas and information in your work.

- Read your assignments and check whether everything that is not entirely in your own words or from your own resources has been acknowledged.

- Make sure that you include in your bibliography anything you refer to in the text and exclude any reading to which you do not make explicit reference. This includes materials that you put in appendices and use in lessons and plans, by the way.

- Don’t be tempted to think that if you have changed a few words from a source you have read that you don’t need to acknowledge it – you do.

- If in any doubt, reference it.

|

Latin abbreviations |

Using the following is conventional but unimpressive if used wrongly.

- i.e.

- means that is, being the abbreviation of the Latin id est. It should not be confused with e.g.

- e.g.

- means for example, and is the abbreviation of the Latin exempli gratia.

- cf.

- means compare with or consult, being short for conferre. In Latin, it was an invitation to the reader to consult an alternative source to compare with what is being said. In English, it usually simply means compare.

- et al

- means and others and comes from the Latin et alia. Use it after the first author when there are more than three authors.

- et seq.

- This is the Latin abbreviation for et sequens and

it means and what follows. It is used to direct

the reader to a page or paragraph in a text and note that this

is where the relevant section starts. For example:

See Smith, 1992:350 et seq. - sic

- This is the Latin for so or thus. If

you want to quote something that is incorrect or oddly phrased,

use this in brackets after the words or phrase to show that this

is how it appears in the original text. That way, the

reader will not think it is your mistake. Do not correct

anything that you are citing directly. For example:

The teacher in the home institution informed me that "this class are mixed of reading level (sic)". - viz.

- is the usual abbreviation for videlicet which means namely, that is to say or it may be said. It should, in theory, not be confused with i.e. although most writers use them interchangeably. Use viz. when you want to give more detail or be more exact.

- q.v.

- stands for quod vide, which means which see and refers to a term that should be looked up elsewhere in a document. It is often used for cross referencing.

- ibid.

- stands for ibidem, in the same place and is used in citations to refer to the immediately preceding citation.

- op. cit.

- stands for opere citato, in the work cited. It is used to refer to any previously cited work, not just the last one.

- pace

- means something like With all due respect to and is used by authors to show respect for the holder of a view with which they disagree (often disrespectfully).

- passim

- means very approximately throughout or frequently and refers to an idea or concept that occurs in many places in a cited work so a particular page reference is inappropriate.

|

Integrating citation |

You are expected at Delta level to do proper research into and

reading about your topic area. You need to demonstrate this by

using appropriate citations from authorities to back up what you

write.

There is more to this than stitching together quotations and leaving

it at that.

Here is an excerpt from a Delta essay concerned with teaching the

skill of producing a spoken narrative, specifically an anecdote.

Your task is to decide what's wrong with it, why and how it could be

improved. When you have made up your mind, click on the

![]() to reveal some comments. Hint: there are more than three

problems.

to reveal some comments. Hint: there are more than three

problems.

| 1 Grammar Anecdotes involve the descriptions of past events. As a result, past verb forms are more frequently used to help to narrate the main events. Storytellers also use progressive aspects to provide a temporal frame around an event or series of events (Thornbury and Slade, 2006). Example: It was two weeks ago, my friends and I were having drinks in a bar. 2 Lexis ... |

|

The morals:

- If you cite, reference and acknowledge.

- Comment on and explain what you cite so that it is clear that you understand the authority's point.

- Make sure your examples are complete and representative of what you are exemplifying.

- Comment on the implication(s) of what you write when citing authority.

- Be critical and think about any exceptions or alternative points of view.

- Choose reporting verbs which express clearly the level of certainty implied in your sources. There is a guide to reporting verbs in academic writing on this site linked in the list of related guides at the end.

|

Style |

This is an academic essay so you need to maintain a certain formality.

- Avoid non-standard abbreviations, contractions and so on. So don't use SS when you mean learners or students, and so on.

- Do not use slang or overly colloquial language. So don't write mess up when you mean confuse or disorder etc.

- Avoid the use of meaningless adjectives such as nice, great, lovely and so on. They carry no sense so consider what you really mean: enjoyable, helpful, effective etc. Do not use incredibly when you mean extremely or just very.

- Use the first person only when you are referring directly to

your own experience. If you want to state your opinion, hedge

it with something like

It can, however be argued from my experience that ... - Hedge what you say in academic terms. Using modality

carefully and including hedging adverbials can be very effective

in achieving a more reasoned and reasonable tone.

This means avoiding writing, for example:

It is obvious that we must ...

and writing something like:

It is clearly arguable that we should ...

For more, see the guide to hedging and modality in academic English, linked below. - Use a range of reporting verbs when you cite or paraphrase

authority. Avoid always writing, e.g.:

Jones (1990:230) states, "..."

or

Jones (1990) says that "..."

and consider something more accurate and meaningful such as:

Jones (1990:230) cautions us that "..."

or

Jones, 1990, observes / notes / makes the point that "..."

For more on a range of appropriate reporting verbs, see the guide them linked below. - Use subheadings which actually relate to the following text.

- Use bullet points sparingly and not as a substitute for connected prose. Lists and tables are helpful but you must discuss their content.

|

Structuring the threads of the essay |

Content: there are four parts to address

Part1: Identification of and justification for the choice of area

The introduction needs to set out exactly what the title of the

essay means.

For example,

In this essay, the focus is on the future forms in English most needed by learners at A1 and A2 (Common European Framework) levels. It covers the analysis of going to, the will future and the use of the present progressive tense.

Then you need to justify it with something like

This area has been

selected for three reasons:

Bloggs (1999: 26) points out that

these forms "are essential to any accurate use of future time forms"

(you have shown reference to

research and reading).

Then you need to draw on your own experience

In my

experience with learners at these levels, there is persistent

confusion regarding ….

(you are drawing on your experience)

Learners need these forms in order to be able to …

(you are showing

you understand the value to learners in general for the area of

focus)

You can go on to discuss specific learners you have

encountered but this is not the place to discuss the class you will

teach – that belongs in the Commentary on the lesson plan.

Part 2: Analysis (for a systems focus)

This means what it says so it takes the form of an information report on each area of focus and each section follows this structure:

- Identifying the topic

- e.g., subheading: going to

- General statement

- e.g., This structure is very common and has two fundamental functions in the language.

- Description

- Form (describe with exemplification)

Pronunciation (with exemplification and transcription)

Meaning and Use / Function (with exemplification)

Part 2: Analysis (for a skills focus)

Here you follow the same three-part structure but the focus is on analysing the subskills (not, please, ways of teaching it). So you have:

- Identifying the topic

- e.g., subheading: scanning

- General statement

- e.g., This skill is employed when the reader is identifying a specific item in a text (such as a date or name).

- Description

- The skill (what it is)

Purpose (why it is used)

Function (how it works)

Part 3: Issues for learning and teaching

This is also an information report and follows a similar structure

for each issue you identify.

(It can, therefore, be combined with the analysis like this:

Analysis of form / subskill followed by the issue for learning or

teaching set out as below. This works well for some topics but

needs careful handling to keep on track. Subheadings are vital

here to guide the reader.)

- Identify the issue

- E.g., with a subheading (e.g.,

Learners’ first

languages differ from English). For some

information about how learners' first languages differ and may

be classified, go to

the guide to types of languages, linked below.

For a skills-focused essay, you may need to discuss how text structures and writing conventions vary across cultures and/or how issues of politeness and deference may affect how people speak. Check out the in-service skills index for appropriate topics. - General statement

- Make a general statement about it referring to your analysis

in Part 2. E.g.:

Learners may be tempted to draw on their first languages to understand the various concepts but languages differ in many ways.

Or, for a skills-focused essay:

In English, the structure of a formal presentation is normally ... but in other languages and cultures such as ... the stages may be ... and learners need explicit training in the conventions or they can confuse and disorient their listeners. - Description

- Now add the detail, for example

Learners from Romance language backgrounds will expect to find specific and recognisable tense forms to refer to the future, while those from other language backgrounds such as ...

Or, for a skills-focused essay:

Learners whose first languages structure texts differently may produce texts whose information staging is unfamiliar to English-language speakers and difficult to access.

In reading, they may be unaware of where to look for information in texts because of a lack of familiarity with conventions.

Now exemplify what you mean.

Now say why it's a problem for learning or teaching or both with an example of the sorts of errors which can occur and how they might affect communication.

Part 4: Teaching suggestions and solutions

This is not another information report. It is a discussion because

it asks you to discuss both advantages and disadvantages of ideas

based on your own experience or teacherly intuitions so it has a

different structure and staging.

This section must be linked back to the content you have already

written, especially the content of Part 3.

This is also the place, in a skills-focused essay, to consider such

things as process and product approaches.

- Statement of position

- something like

To address the issue of …

Refer explicitly to the issue identified – do not require the reader to figure out what issue you are talking about. - Preview of argument

- For example,

In my experience guided discovery procedures are effective because ... - Description

- Here you describe what the technique / procedure / materials

are, using an appendix for detail. Supply enough detail here to

make the procedure clear, however. For example

This procedure involves three steps. Firstly, ...

Then set out the staging clearly. - Evaluation

- This is a kind of coda, saying how and why you think what

you are suggesting is useful and pointing out any drawbacks.

It can come in two parts:

Arguments for with evidence: here you say what it helps with and why – draw on your experience to evaluate. For example:

I have found that this procedure is effective in alerting learners to the need for ...

Arguments against: here you state the shortcomings (if any) of the procedure / materials etc. For example:

Without careful preparation, however, this procedure will not evince the language target so it must be preceded by ...

And so on for the rest of the ideas. You should have at least four and they should be of different types – presentation ideas, practice ideas, consolidation procedures and activities, focus on form, focus on function etc.

Conclusion

If you need a conclusion, keep it short and to the point. Do not repeat what you have said – sum it up.

Proofreading

Your essay should be free from slips and errors. The syntax should be clear and the reader should be guided through the essay with subheadings. Make sure the subheadings actually reflect the content of what follows.

|

Balance |

The core of your essay is the analysis, the identification of

learning and teaching issues and the practical solutions you put

forward to address the issues you have identified in both those

sections.

You have 2500 words to apportion so any that you spend elsewhere

will detract from the core. All essays are different, of

course, but here's a suggestion (only) for how to balance the various

parts in terms of words expended:

- The introduction

200 to 300 hundred words to cover the identification of the topic and scope, the reasons it is important and the references to your teaching and your reading and research which made you select this subject. - The analysis and issues for learning and teaching

1200 or so words in total to cover both those areas with clear exemplification (however you organise the sections, see below for the choices).

If you find your are going to write more than this, re-visit the title and the Introduction and narrow the scope somehow. - Teaching solutions

800 to 1000 words to cover an outline of the procedures and materials etc., a statement of what issue(s) they address and how they address it and an evaluation of their effectiveness (good and bad). - Conclusion

50 words or less. Some centres seem to want you to write a conclusion, some don't, but if you must say something here, keep it short and very focused. You do not have words to squander.

Visualising the essay structure

Here's a diagrammatic way of seeing the structure of a good Delta essay with sections overlapping and linked together. You could print a copy to have in front of you as you write.

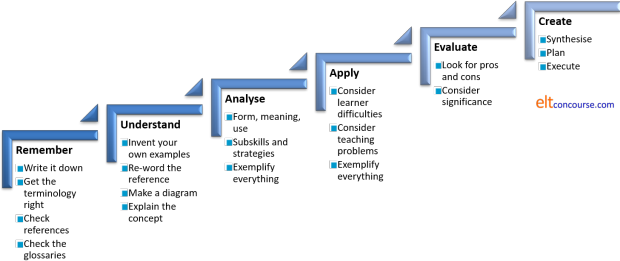

In terms of skills you need to use to write an essay, there is a guide on this site, linked below, to things you need to know how to do. There are six of them and they are summarised in that guide like this:

|

Organising the core of the essay |

The two key sections are the Analysis and the Identification of learning and teaching issues. There are three ways to go about organising this section. You choose, but don't mix them up. Decide how you will do it and stick to the pattern or the reader will get confused and irritated.

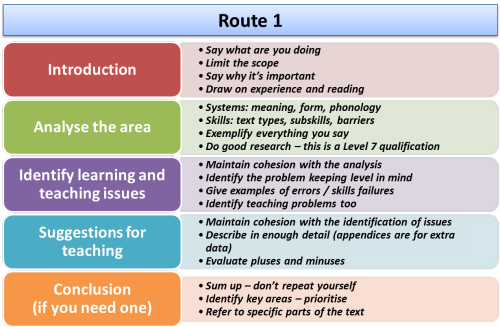

Route 1: keeping the parts separate:

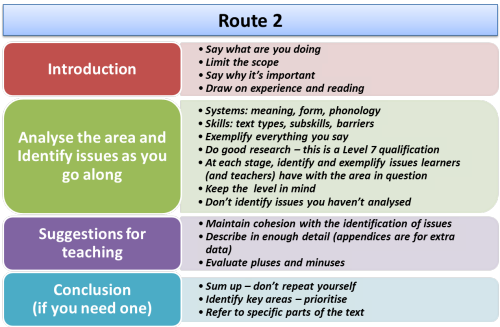

Route 2: combining analysis with issues:

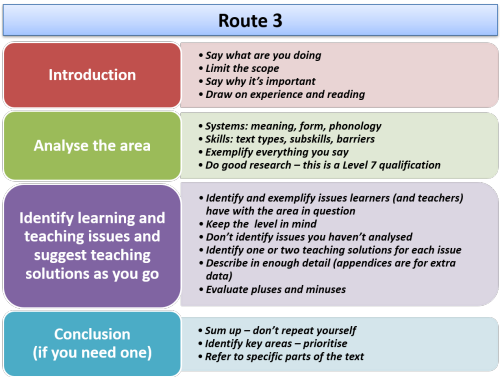

Route 3: combining issues with solutions

Each route has advantages.

- Route 1 (keeping things separate)

- This is simpler but requires you to be very firm about

coherence and make sure that the identification of issues only

deals with things you have analysed. Do not suddenly bring

in something new here.

You need to make explicit reference from the identification of issues back to your analysis.

Make sure you identify at least one issue in each area of analysis (meaning, form, phonology or skill, subskills, use, purposes).

Be clear how the teaching solutions refer to the analysis and issues you have identified. Do not target a new area that you have not previously discussed. - Route 2 (combining analysis and identification of issues)

- This almost ensures that you will be coherent because each

area of analysis is followed by the discussion of difficulty.

You may lose the thread if you find that there is an analysis area for which you cannot identify a problem. You may even be tempted to invent a problem that doesn't really exist.

You still need to make explicit reference from the teaching suggestions to both analysis and identification of issues. - Route 3 (combining issues with teaching solutions)

- This route, too, will help you maintain linkage and

coherence because each issue you identify is followed

immediately by a teaching solution or two.

You will need to keep an eye firmly on the discussion in the analysis to make sure you not identifying an issue you have not analysed.

You will still need to make explicit links to the analysis.

You may be tempted to insert more analysis here and that will lead you astray. If you are tempted, go back and insert the analysis where it belongs.

|

One to avoid |

Do not be tempted to combine Analysis with

Identification of issues and Teaching suggestions.

That way, madness lies.

The essay will become incoherent and difficult to follow because too

much is intertwined.

If you do all this, you will have a properly structured Delta Background Essay which will pass (providing what you say is accurate and believable).

| Related guides | |

| the assessment criteria explained | for a break-down of the criteria and what they mean |

| a style guide | for a guide to writing in appropriate, formal, academic English for Delta |

| study skills for Delta | this is a guide to the skills you need to deploy when writing for Delta |

| your first Delta essay | for more examples and advice based on a systems essay |

| getting a distinction | for a more detailed analysis of how to meet all the essay criteria above pass level |

| analysing systems | for some advice concerning the levels of depth, detail and precision which are required to meet the criteria in section 3 |

| analysing skills | |

| researching language online | a short guide to whom to trust |

| getting a distinction | how to meet all the criteria above pass level |

| genre in EAP | for a guide to the staging and structuring academic texts |

| hedging in EAP | for how to use modality and other academic hedging |

| reporting verbs in EAP | for how to use a range of reporting conventions |

| language typology | for a guide to what to look for in other languages |

| the in-service index | for guides to language systems and skills at this level |