CELTA Syllabus

Topic 2: Language analysis and awareness

|

... language learning is essentially learning how grammar

functions in the achievement of meaning and it is a mistake

to suppose otherwise. .... A communicative approach does not

involve the rejection of grammar. On the contrary, it

involves a recognition of its central mediating role in the

use of and learning of language. (Widdowson, 1990: 97/8) |

Each section of this guide is brief and contains links to guides

elsewhere on this site. Following those guides will prepare

you well.

You should look for the areas of language analysis which are

particularly important to you (because, e.g., you are teaching them

tomorrow). To do that, go to the initial plus training section

or search for what you want by using this link:

search the whole

ELT

Concourse

site.

The A-Z index

of the site is also a good place to begin.

Searching from there may take you to some of the

more advanced language analysis guides. But why not?

Native and non-native speakers of English

- If you are a native speaker of English:

You actually 'know' all the grammar in one sense, insofar as you can speak the language and have no trouble forming grammatically correct utterances (usually). What you probably don't have is what is called declarative knowledge and that is what prevents you from being able clearly to explain grammar to learners or to plan and teach the grammar input they need.

In Britain and many other English-speaking countries grammar is not taught thoroughly or even at all in most schools. The spin-off from this is that many teachers (and some teacher trainers) know embarrassingly little about the grammar of their own or anyone else's language. - If you are a non-native speaker of English:

You have a distinct advantage. You know the grammar pretty thoroughly and probably know lots of terminology to talk about it as well. What you need to be careful not to do is visit on your students the awful things that happened to you. Swan puts it this way:

Many foreign-language teachers spent a good deal of time when younger learning about tense and aspect, the use of articles, relative clauses and the like; they naturally feel that these things matter a good deal and must be incorporated in their own teaching. In this way, the tendency of an earlier generation to overvalue grammar can be perpetuated. (Swan, 2002)

|

Why do I need to analyse the language? |

|

|

Task 1:

Well, why do you? Click here when you have made a note of some reasons you should be able to analyse and teach the systems of English. |

- Dealing with error

- You can speak the language, of course, and you can immediately spot when an utterance is malformed or grammatically flawed. However, especially if you are a native speaker, you may be at a loss to know what exactly has gone wrong and the best way of explaining what's right. You need to be able to analyse language on the hoof, not just in your study.

- Teaching formal structures

- There are times when learners of English (most of them) need

to learn how a structure works. There are two reasons for

this:

a) As Swan puts it:

"Knowing how to build and use certain structures makes it possible to communicate common types of meaning successfully. Without these structures, it is difficult to make comprehensible sentences. We must, therefore, try to identify these structures and teach them well."

That mirrors the view of Widdowson, above.

b) Swan again:

"In some social contexts, serious deviance from native-speaker norms can hinder integration and excite prejudice – a person who speaks ‘badly’ may not be taken seriously, or may be considered uneducated or stupid. Students may, therefore, want or need a higher level of grammatical correctness than is required for mere comprehensibility." - Learner expectations

- Most adult learners are aware that they need grammar to communicate and will neither trust nor respect teachers who can't teach it, correct it and explain it or don't seem to know their own subject thoroughly.

|

Where do I start? |

If you have never analysed language before, there are three short courses and a reference section on this site to help. Links in this table open in new tabs.

| a pre-course guide | This is where you can see what you need to know and follow links to essential guides. |

| a CELTA grammar course | This is short but covers most of the grammar you need to know for a CELTA course. |

| A Basic Training Course | This is a very basic course for people with no teaching experience. |

| A Language Analysis Course | This 10-unit course covers the elements of pronunciation, words, tenses, aspect, phrases, clauses, sentences and text structures. |

| A Simple English Grammar | This is written for elementary students and will help you to explain simply some grammatical ideas in the classroom. |

This is what this area includes. Click on the area which

interests you for more. (Click on

![]() to return.)

to return.)

|

Basic concepts and terminology |

The primary distinction to get clear before you can begin to learn about the language (any language, in fact) is that between form and function:

- Form

- concerns the structure of the language. For example,

if we are faced with a sentence such as:

That man is asking me about the new Lenovo laptop

We can analyse the sentence like this:- That man

= the Subject of the sentence (and everything that follows

it is called the predicate). It consists of:

a determiner (that) and a common noun (man). The noun tells you what I am talking about and the determiner tells you exactly which one I am talking about. - is asking

= the verb phrase. It consists of:

a primary auxiliary verb (is) and a verb in the -ing form (asking). Together these form the present progressive tense which tells you that this is happening right now. - me = the object of the sentence. It consists of only one word, the pronoun me which tells you whom the asking is directed at.

- about the new

Lenovo laptop = a prepositional phrase.

It consists of:

a preposition (about) which signals a topic and a noun phrase (the new Lenovo laptop) which in turn consists of a determiner (the) which suggests you already know the one in question, an adjective (new) which describes the noun phrase and the noun phrase (Lenovo laptop) which has two parts:

Lenovo which classifies the noun and laptop which is a simple common noun.

Word class which tells us what kind of word or phrase we are dealing with (nouns, verbs, adjectives etc.)

Syntax which tells us the relationships between the parts of the sentence (Subject, Object, Verb etc.)

If you follow the very short pre-service grammar course on this site, linked below, you, too, will be able to do this kind of analysis quickly and accurately. It will be required of you on a CELTA course and a decent one will teach you how to do it. - That man

= the Subject of the sentence (and everything that follows

it is called the predicate). It consists of:

- Function

- The other way we can analyse the same sentence is to look at

its function in terms of what it communicates. For this,

because the sentence is not in a text or conversation, we have to

make some assumptions.

- The setting = a shop. This seems a reasonable assumption about where the sentence might be spoken. It's not the only possible one, of course, so we need to keep an open mind here. The setting, whatever it is, will usually tell us something about the meaning of what is said.

- The participants = a salesperson and a colleague. This, too, seems a reasonable assumption, if the first one about the setting is correct, because it's hard to see who else would utter the sentence.

- The relationship

between the participants = unequal,

knower to non-knower or subordinate to manager. Again,

because we have nothing else to work on, we have to assume that

this is the case. There seem to be two likely

scenarios:

- this is a manager using the sentence to direct a subordinate to go and help the customer

- this is a salesperson who is asking a colleague to help the customer because he knows too little about the laptop to be informative enough.

- Meaning

= the communicative value of the sentence. Again,

depending on the roles of the participants, there are two

possibilities:

- it is an order dressed up as information

- it is a request for help similarly dressed

This is a very important point because it is impossible to know the function of language unless you know these things. You can see that with the analysis of form, no assumptions were made because we are not dealing with meaning.

|

Grammar |

Many people have made long and distinguished careers from the

academic study of grammar and continue to do so.

That is not required of you but you do have to know about the

subject you are teaching. If you don't, people will soon

notice and you will have a hard time in the classroom.

Grammar may be defined quite broadly to include the structure of

sentences as well as the words we use to make them and the sounds we

make when we speak.

Often, however, grammar is more narrowly defined as to do with

structure alone and words (lexis) and sounds (phonology) are given

categories of their own. This is the approach taken here.

Nobody but you knows how much or how little you already know about

grammar but you will need to know or learn about at least the

following and there is a link below to a CELTA grammar course which

covers most of them.

- sentence structure: subjects, verbs, objects, adverbials, phrases and clauses and how they all fit together. This is usually defined as syntax.

- verbs and tenses: lexical or main verbs (which carry real meaning),

primary auxiliary verbs (which operate grammatically to make

tense forms and more) and modal auxiliary verbs (such as

may, can, might, would etc.) which signal the speaker's

view of the main verb.

This area will also include knowing the names and the major functions of the 15 main tenses used in English. That's not as difficult as you may think but you will have to get to grips with the difference between tense and aspect because that is fundamental to English forms. - word and phrase class: adjectives, adverbs, nouns, verbs, prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns, determiners and interjections.

- other major structures which include but are not limited to: passive clauses, causatives, quantifiers, coordination and subordination and quite a lot more.

|

Lexis |

In addition to word class, usually the concern of grammar (see

above), you need to know something about the categories into which

words are divided and the relationships between them.

Lexis is the term used in English language teaching to talk

about words and vocabulary. The reason for this is that it

is very difficult to define what is meant by the term word

because a word (which is a group of letters written with a space

at each end) may

- have no meaning

For example:

There is no doubt that the, in, out, my, between, but, this, some, few and many more items are words in the usual sense but it is very difficult to assign a meaning to them or to explain what their significance is.

On the other hand, words such as table, tree, happiness, yellow, ride, extraordinary, sadly, grow, often etc. clearly do carry a meaning and can, in fact, be the only item in a sentence and still have some communicative value.

What we are talking about here is the distinction between function words, the ones without much meaning if any at all, and content words, the ones which do carry meaning. - not be single

words

For example, it is clear that:

The Democratic Party

is a single idea and that it is used to refer to a single entity but it consists of three words. In our profession, it's called a lexeme. Another example is:

cream tea

which is neither cream nor tea but forms a single concept consisting of two words. It, too, is a lexeme. - take a variety of

forms

For example, sink, sank, sunk, sunken, sinking are all words in the normal sense of the term but they constitute a single lexeme because they are just slightly different grammatical forms of the same idea.

Once we have determined that the term lexeme is a better one to work with, we can look at relationships between them. That allows us to talk about, for example:

- synonymy

For example:

The words freezing and icy both mean very cold so they are synonyms in terms of meaning. Unfortunately for our learners, there are very few absolute synonyms in any language so while we can have:

a freezing wind and an icy wind, we cannot have a freezing road so must select an icy road. - collocation

This refers to what we saw in the last example. Collocation describes the fact that many words have preferred partners, so to speak. We can, therefore, say:

a strong wind and heavy snow

but we cannot have

a heavy wind and strong snow

because heavy does not collocate with wind and strong does not collocate with snow. - antonymy

For example:

The words big and small have opposite meanings so they are considered antonyms. As we saw with synonyms (above) however, collocation plays a part here, too and not all antonym pairs can be used in the same way. We allow:

a thin line and a thick line

but not

a thin dog and a thick dog - hyponymy

For example:

The word building includes:

house, church, school, office block, cottage, palace and many more so:

building is the hypernym or superordinate and the words for types of buildings are all hyponyms of each other.

There are many more relationships between lexemes which can be

identified and analysed but the four above are all you need (for

now).

The final idea in this section is the term morpheme.

If we look at this word, for example:

unprintable

we can see that it is made up of three parts:

un,

print

and able,

and all three are referred to as morphemes but there are two

sorts:

- un

is a unit of meaning but it cannot stand alone and always appears with other morphemes so we call it a bound morpheme.

Other examples are: ize in computerize, dis in disorganised and so on. - print

is a unit of meaning which forms part of our example but it can also stand alone as a single lexeme so we call it a free morpheme.

There's a good deal more to be said about morphemes, of course, but this is enough for now.

|

A note on style and register |

The revised CELTA syllabus (from July 2021) now distinguishes

between style and register instead of just talking about

register as if it included style.

Briefly:

- Style

refers to a level of formality which is appropriate to the setting and the relationship between speaker and hearer or writer and reader.

There are a number of different ways to classify styles and the one used on this site distinguishes between- frozen style (used for notices and quotations etc.)

- formal style (used for lectures, speeches, technical presentations etc.)

- consultative style (used for professional interactions such as those between doctors and patients, teachers and students etc.)

- casual style (used between friends and relationships with little concern for formal accuracy and so on)

- intimate style (used between people who are very close and share a lot of information).

- Register

refers to the topic and setting in which the language is used which may require, for example, specialist vocabulary and ways of expressing things.

Many of these are to do with professional settings but there are also special registers attached to sports, hobbies and other areas of interest which require the use of some special vocabulary and language use.

Style and register are different as you see but they are often considered in tandem because certain registers such as business meetings, professional consultations, lectures and so on often require language specific to the topic but also a certain level of stylistic formality. That is not to say that one cannot use an informal style in a lecture in the register of, say, scientific enquiry, or that one cannot use a consultative style between people talking about football (as in a TV interview, for example).

|

Moving on |

OK. Now you have all that clear, you can get on. There are two choices for you:

- Go to the CELTA grammar course now and familiarise yourself with the concepts and terms we need (it's called metalanguage, incidentally) to talk about language systems. To do that, open the first link in this table.

- The second alternative is just to go on and try to

absorb the terminology as you work through the guides of your

choice. That's the way most CELTA courses expect you to

learn the terminology and understand the concepts. To do

that, click the second link in the table.

Guides Content The CELTA grammar course This is a four-part course which only covers: word and phrase class, syntax, conjunction and verb forms. It's enough for now. The initial plus index From here, you can access any of the guides in the initial plus section of this site. If you have time and need more information, try some of the following: terminology in ELT This covers a basic range of different kinds of terms to describe the language and teaching the language. grammar glossary This is a reference guide for people on a pre-service course such as CELTA. phonology terminology This covers the essentials of the language we use to talk about pronunciation. other glossaries For a list of all the glossaries on this site. English tenses This gives you a summary of the names of the tenses in English and what they do. the sentence This explains the types of sentences that exist in English and what they are called. word class essentials This guide cover what you need to know about the different sorts of words in English (nouns, adjectives, pronouns etc.). subjects and objects This will teach you about how English deals with the important noun phrases which make up part of almost all sentences.

|

|

|

Phonology |

| 'eee' /iː/ | aah /ɑː/ | sh /ʃ/ |

Phonology is the study of the sounds of a particular language (not all languages; that's phonetics), in our case, English.

Here, too, there are some basic ideas you need to be clear about

and a CELTA course will focus on them. This is a technical

area and you are not expected to be able to transcribe the sounds of

English accurately or to be able to analyse some of the most

difficult areas of connected speech but there are a few terms that

you need to be familiar with or you won't be able to talk or read

about pronunciation (or teach it) successfully.

(If you are taking the Trinity CertTESOL course, more will be

expected of you in this area because a major difference between the

two courses concerns the thoroughness with which pronunciation is

dealt with on the Trinity courses.)

Here are the key terms everyone needs to know:

- Phonemes

- are the sounds of a language. We make a difference

between them and the letters which spell words for the simple

reason that English (in common with many languages) does not

have a one-to-one relationship between spelling and

pronunciation. For example, all these words end with the

same sound:

cough, laugh, graph, ruff

that sound is written as /f/ between two lines to show that we are representing the sound not the letter. All phonemes are written that way so we get, for example, /t/, /h/, /d/ and so on. - Vowels

- you may think that English has five vowels, a, e, i, o and

u, and that is what most people believe. However, there

are in fact 21 sounds in English which are classified as vowels.

They are the sounds underlined in red:

go, find, father, choose, bring, happy, how and many more, of course.

All lexemes in English contain vowel sounds even if they do not contain vowels in their spellings. - Consonants

- There are 24 of these in English and most are represented by

familiar letter as phonemes so, for example /t/ is the sound at

the beginning of top and /p/ is the sound at the end.

A few consonants have special symbols such as /ʃ/, /ð/ and /ʒ/ but they are not difficult to learn. - Connected speech and citation forms

- If someone asks you to say an isolated word out loud you

will usually opt for what is called the citation form so, for

example, if you are asked to say

to, for, been out loud, they will

sound the same as too,

two, four, bean.

However, if you say the words in a sentence such as

She's been to the shops for two tins of beans and four sausages

you can hear that the pronunciations of the words is now altered and they do not sound the same.

The reason for this is complicated but the result is that we have what are called weak forms of to, for and been in the connected speech example. - Stress

- refers to how loud and long a part of a word or a word is

pronounced. So, for example, on a word like:

happiness

the stress falls at the beginning on the 'a' and we can represent that as:

hAppiness

but on a word like

impossible

the stress is on the 'o' and that looks like:

impOssible

That's word stress.

In whole sentences, too, we hear the same sort of patterns so, for example:

What have you done?

is stressed on the final word so we can represent it as:

What have you DONE?

and that's sentence stress. - Intonation

- refers to how your voice tone rises and falls on certain

parts of what you say. For example, if you say the word

Really as the response to something you hear you can

sound:

excited (Really!↑)

bored (Really→)

sceptical (Re↑ally↓)

and so on.

When we make a question, too, we often rely on intonation to make the function clear so

That's your car?

and

That's your car

will have different intonation patterns (rising at the end of the first sentence and falling at the end of the second).

That's just about all you really need to know on a CELTA course about pronunciation but ...

| More information can be had from | ||

| The initial plus pronunciation index | A course in transcription | The in-service pronunciation index |

|

Similarities and differences between languages |

Many people have made long, honourable careers out of the study

of what is known as comparative linguistics.

You don't need to do that but you should have a basic understanding

of how English works and how it is similar to or different from your

learners' language(s).

Languages differ, obviously, in their grammar, pronunciation and lexis in many ways (some bewilderingly so). However, there are also major differences and similarities to be aware of:

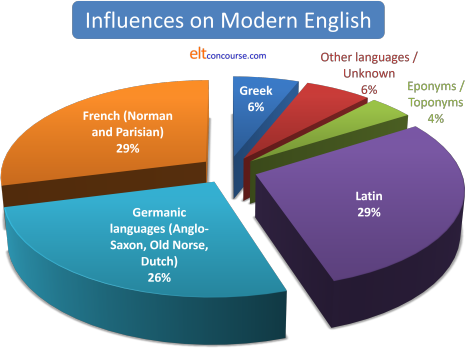

- Lexis

The English lexicon is, like those of many languages, drawn from a range of influences which have contributed to it at one time or another.

For modern English the picture looks like this:

(Eponyms and toponyms are words named after people, businesses and places such as hoover, wellington boots and so on.)

This has consequences for learners of English, obviously:- Speakers of Germanic languages (Swedish, Norwegian, Dutch, Flemish, German, Danish and more) will have little trouble identifying short, common words such as book, house, land, finger, thing and hundreds more.

- Speakers of Romance languages, based on Latin or akin to French such as Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Romanian and associated ones) will be at home with words (often for abstract nouns) derived from French or Latin such as conversation, argument, atmosphere, entertainment, frequent and so on although not all of them will be similar in all those languages.

- Speakers of Greek will have very little to draw on because

most of the lexicon is completely different and speakers of

unrelated languages such as the Chinese languages, Korean, Thai

and Japanese will have almost nothing to draw on except a few

unusual loan words like origami, bonsai, ginseng, lychee, typhoon

etc. Speakers of Thai will have nothing at all to

draw on.

For all these learners, acquiring vocabulary in English is very difficult.

- Grammar

Although English derives some 60% of its words from either French of one kind or another or Latin, the grammar of the language is much more Germanic.

Speakers of Germanic languages, such as Dutch, Swedish, German, Danish and Norwegian will, therefore, find learning grammatical structures a good deal easier than people whose first languages are in a different group such as Romance languages (e.g., French, Italian, Spanish, Romanian), Greek, Slavic languages (e.g., Polish, Russian, Czech etc.) and so on.

Of course, people whose first languages are wholly unconnected to English such as speakers of Chinese languages, Korean, Japanese, Thai, Arabic, Turkish and so on will find very little to help them either in the grammar or the lexis of English. - Word order

In English we do the following:- we order the main parts of a sentence as Subject–Verb–Object

as in

The man | drove | the car

Other languages do things differently and Japanese, Turkish and Hungarian, for example usually have Subject–Object–Verb as in

The man | the car | drove - we place the adjective almost always before the noun so we

have:

the incredible expense

not

the expense incredible

but many other languages, including French, Spanish, Thai, Russian, Czech, Polish and others place the adjective after the noun. - we place the preposition before the noun phrase so we have

over the bridge

not

the bridge over

and that's why they are called prepositions.

Other languages, such as Turkish, Japanese and Korean do the reverse and have postpositions as in:

I walked the house past - we have two ways to show possession or origin. We can

say:

the government's policy

or

the policy of the government

and there are complicated rules to decide which one to use.

Most other languages settle for one or the other.

- we order the main parts of a sentence as Subject–Verb–Object

as in

- Pronunciation

As we saw above, English has 21 vowel sounds and 24 consonant sounds and many of them such as the way we pronounce th or sh do not exist in other languages.

Many languages have sounds that do not exist in English, too, or they make distinctions between the ways some sounds (such as /p/ or /t/) are pronounced which English speakers do not recognise.

On the other hand, many languages have sounds which are very similar to the one which are used in English and with these, nobody will have too much difficulty, although there are subtleties in, for example, the way the letter 'r' is pronounced that are part of our being able to recognise a foreign accent in English. - Morphemes

We saw above that English can build words from morphemes to make longer and more complex lexemes. Other languages, such as German and Turkish do this much more enthusiastically but some, such as the Chinese languages, hardly do it at all.

| More information can be had from | ||

| The essential guide to word order | Types of languages | Teaching troublesome sounds |

(The third link to teaching troublesome sounds relies on you being able to read the phonemic script.)

|

Reference materials |

Go here

for a summary of the sorts of materials and references that are

available to help you learn about the systems of English, especially

its grammar.

This site is not a bad place to start, too.

There is a separate guide on this site to

doing online research which you should look at if you want to

know whom to trust. There are, alas, many sites out here

written by people who know very little about English and they will

lead you astray.

|

Key strategies and approaches |

There is some confusion, not least in the CELTA syllabus,

concerning what counts as an approach, a strategy and a procedure

in teaching methodology.

The line taken on this site, which may well differ from what your

tutors say, is:

- Approach

- refers to having two underlying theories:

- a theory of what

language

It can be two things in the main:- that language is a system of structures which include phonemes, morphemes, words, phrases, clauses and sentences which are built up into meaningful language

- that language is a means of communication and can be analysed in terms of social meanings dependent on the speakers' intentions, roles, settings and so on

- a theory of how

learning happens

Here, too, we two opposing (and incompatible) views:- learning is a process of encountering the language in a meaningful context, thinking about it, trying out hypotheses and eventually acquiring the systems and the communicative skills you need

- learning is a process of being exposed to carefully graded and selected language demonstrating its structures and then, through a process of repetition and drilling acquiring the habit of producing correctly formed utterances

- a theory of what

language

- Strategy

- refers to hypotheses about how

the mind works and how people acquire a second language.

There are two connected strings:

- strategies for

learning

These can be, for example, learning word lists, using grammar books, speaking as much as possible, listening to native speakers and noticing how they use language, reading widely in English, attending to the grammar and seeing how it differs from the learners' first language(s) and so on. - strategies for

teaching

These can be, for example, presenting language in clear social contexts, using reading and listening texts to highlight lexis and grammar, focusing on skills to attack texts, encouraging learners to be autonomous, making sure concepts are understood, encouraging habitual responses in language and so on.

- strategies for

learning

- Procedure

- Here we are on thin ice because some use the term to refer

to how a lesson is structured, which can be in three main ways:

- PPP

This stands for Presentation–Practice–Production and simply means that we can follow that procedure by presenting a new language item in context, getting learners to practise using it in a controlled way and then allowing them and encouraging them to use the language for a communicative purpose such as saying something personal in the language. - TTT

This stands for Test–Teach–Test and means that we follow a different procedure, first testing what the learners can do in the language or with a skill, so both they and we are alerted to what needs to be learned, then teaching it (perhaps using a PPP approach) and finally testing again to see and show how much has been learned. - TBL

This stands for Task-based Learning and involves a rather different procedure. It can be- setting a task (with a model if necessary), allowing

the learners to carry it out with the language and

skills they already master and then filling in the gaps,

as it were, with teaching of the language they should

have used

or - teaching the language learners will need, setting the task and then encouraging the learners to use the language to achieve the outcomes

- setting a task (with a model if necessary), allowing

the learners to carry it out with the language and

skills they already master and then filling in the gaps,

as it were, with teaching of the language they should

have used

- PPP

Other people, who may include your tutors, use the term procedure much more loosely to refer to classroom techniques such as using dictation, drilling, setting sentence-completion tasks and a host of other ideas which you will learn about on your course. There is nothing wrong with using the term procedure in that way but we should be clear about what we mean when we say something like Try this procedure.

There are a number of guides to teaching many areas of the

language on this site.

Go to either the

in-service or the

initial plus

training indexes to select what interests you now. The latter

has guides to Teaching: background, methodology and techniques and

that's an excellent place to start but don't try to do it all at

once. Familiarise yourself with what's there and come back later.

The links below will lead you to guides to the other areas of the syllabus and to an overview unpacking what the syllabus means and how it is assessed.

| Topic 1 | Topic 2 | Topic 3 | Topic 4 | Topic 5 | Unpacking | The CELTA Index |

| Learners and teachers, and the teaching and learning context | Language analysis and awareness | Language skills | Planning and resources for different teaching contexts | Developing teaching skills and professionalism | Unpacking the syllabus and assessment | The index of all the CELTA guides |

References:

Swan M, 2002, Seven bad reasons for teaching grammar - and

two good reasons for teaching some, in Methodology in Language Teaching,

(Eds.) Richards and Renandya, CUP 2002,

pp.148–152

Widdowson, H, 1990, Aspects of Language Teaching, Oxford: Oxford

University Press